Prologue

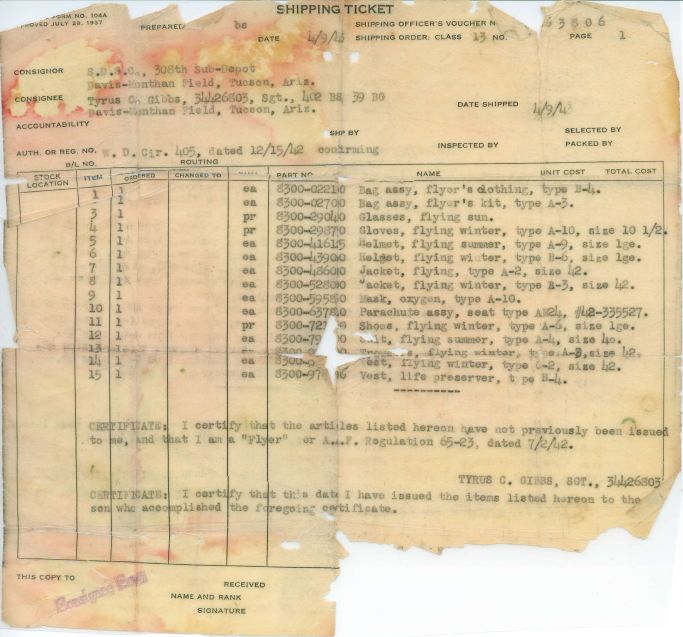

| Principal person: | T.C. Gibbs |

| Position: | Air gunner (nose turret) B-24 bomber |

| Unit: | US Army Air Force |

| Plaats van handeling: | Air war over Europe |

| Periode: | September 1942 – October 1945 |

The memories of Staff Sergeant T.C. Gibbs have been made available to Go2War2.nl by Dennis Notenboom and have been subsequently copied into typing by Bram Boonstra and Marloes de Krom.

Originally the chronicles have been edited for his descendants and demonstrate a remarkable good memory for facts and figures. The very readable story provides a good impression of what the American war efforts demanded of their Forces. They were very well trained and were subsequently put into active service far away from home. Gibbs provides an insight of the involvement of a care free youngster with his homeland and with the demanding tasks that he was required to perform.

It is a story well worth reading and the part about his bomber aircraft being shot down near the Dutch coast brings him very close to our readers. He is captured by the German forces in the occupied territory of the Dutch province of Zeeland, after the whole ten men strong aircrew of the Liberator has parachuted to a safe landing.

In 2007 T.C. Gibbs was invited by Dennis Notenboom to come and visit the Netherlands. At the meeting at the occasion of the fifth anniversary of the STIWOT foundation, he provided a lecture on his experiences during the war.

Until his death he lived together with his wife Anne in the USA in Tupelo, Mississippi. He died on 9 December 2013 at the age of 92.

Nederlandse vertaling: T.C. Gibbs in het Nederlands

Nederlandse vertaling: T.C. Gibbs in het Nederlands

Images

Prior to entering the armed service

In the fall of 1941 I transferred from Mississippi State College to the University of Mississippi. The reason simply was that MS State had 2,000 male students and less than 100 females – a very bad ratio. Also, Ole Miss was a small school, less than 1,000 students with a fine ratio of almost 50/50 males and females. Since I was an excellent history and political science student, the field of law was chosen for my major. In fairness, it could be said that sororities were my major and minor.

While at Ole Miss, 33 of us enrolled in the Civil Air patrol (CAP) training. At that time many of the students looked down on us, something akin to a gang of ruffians in a motorcycle gang. Yet, when Pear Harbor happened, we became the “fair-haired” boys. (I had been home to Fulton; stopped at my brother Paul’s service station for gas when the radio music was interrupted to tell about the attack at Pearl. Many of us thought it was another Orson Welles Program. It wasn’t.) The next day all Ole Miss classes were dismissed so that students could hear the President and try to learn more about what was happening.

In 1941 during my school Christmas holidays, the family went on a vacation trip to Miami. While we were travelling north on U.S. 1, a “black out” was imposed. We were around Port Pierce, FL when this happened. It was a rather eerie feeling. Suddenly, all lights go out. This was, I believe, the first “black out” in the U.S.A.

Duke and one of the West Coast teams, I’m not sure which one, were to play in the Rose Bowl on January 1, 1942. There was a sudden switch to Durham, NC, so we headed on toward Durham. Yet, with the “black outs” and talk of what could happen, we turned west toward home. This trip was made by Mother, Dad, Paul, Bonnie Ruth, and me.

After Christmas at a called CAP meeting, the 33 enrollees had to choose our future careers as pilots. Thirty chose the US Army Air Force, and three of us chose the Navy. I was the only Navy signer to survive the war. The other two were killed while flying in the Pacific. On May/June of 1942, we were given our CAP license. (It was after the war that I learned the CAP trainees were granted automatic deferments from the draft in order for us to complete our pilot training.)

In June/July, 1942, I was ordered to report to Birmingham, Alabama for mental and physical tests prior to entering the Navy. The recruiter giving the mental said he had only given one test where the score was higher than mine. Next came the physical. There were about ten of us undergoing the physical tests. Everything went well. I could just see myself taking off of a flattop in a Navy fighter plane, shooting down Zeros by the dozens. A doctor asked for the cadet to step forward, I quickly responded. This was the last exam prior to being sworn into the Navy. This particular doctor kept his stethoscope to my chest too long, continually moving front and back, then calling another doctor into the examination. In a short time, after consultation with the second doctor, the boom fell. The sentence of doom was something in this manner.

“Young man, you have a murmur of the heart. No branch of the service will accept you.”

My world had just collapsed around me. I was 4-F!

The return trip home to Fulton, a distance of 120 miles, seemed too difficult having to face Mother and Dad with such news. Paul was a lieutenant in the Army – the kid brother a very miserable 4-F. The oldest brother, Jimmy, was too old for the service and I was physically unfit. It was a bitter pill. For the rest of July and August, I tried to enlist in the Paratroopers, Marines, Navy, or whatever. The CAP in Memphis called me to report there for possible assignment. I promptly reported only to be rejected on the same grounds that all the services had said, “Waste of our time with your heart problem.” None of the places I tried to enlist would even bother to give me a physical exam.

Yet, the world wasn’t coming to an end in the summer of ’42. There I was, twenty-one years of age, a single male, driving a new 1942 Cadillac, (Dad bought the car in November, 1941. The Navy later tried to buy the car to use for a top Admiral. Dad refused telling the Navy he was saving it for his sons in the service). There were few males around, so in a sense, I had the pick of the litter. I recall a night one of my friends was home on leave and he and I had four very attractive females – one redhead, one blonde, one brownette, and one brunette in the Cadillac with us. About two cases of beer, a bottle of gin, and a bottle of Old Crow were also with us when we tried to pick up two soldiers who were hitchhiking so we could even out partnerships. The soldiers looked in the car. The young ladies tugged on their arms, yet the older of the two soldiers pulled his buddy back and refused our invitations. No doubt he thought it was too good to be true. We even told the boys that they could pick the girls of their choice. They still refused, even though there were some very amorous proposals made to them. I often wondered what they told the fellows back at their barracks. If they told it as it happened, no one would have believed them.

As September rolled around, it was time to head back to Ole Miss. About this time, the local draft board sent me a notice to report to Camp Shelby at Hattiesburg, Mississippi. To me this would be a round-trip to Hattiesburg and a quick return home, then on to Ole Miss. At this time the draft boards were scraping the bottom of the barrels for draftees. There was a man on our bus with a wooden leg. Upon arrival at Camp Shelby, we were herded into the examining rooms, stripped naked, and given rushed physical exams.

To each doctor my comment would be, “I have a heart murmur.”

The doctor’s comment would be, “Next.”

The one-legged man was rejected, the rest of us were inducted into the service. I was now in the military service, no longer 4-F.

When we were being given our shots of typhoid, etc., we walked down a line and were popped in each arm. An old boy from home, Paul Dill – a tall, lanky, farm boy, was laughing at everyone flinching as they were hit with the needles. Always laughing and cracking jokes, but when they popped him, he fainted dead away. Paul never lived that down.

After the surprise and shock of being inducted into the service, a quick call was made to Mother and Dad. As was expected, Mother was crying, telling me to take care of myself, write and call often, and Dad telling me to make a fine soldier, give my best and serve my country with pride. That I tried to do.

Definitielijst

- mine

- An object filled with explosives, equipped with detonator which is activated by either remote control or by colliding with the targeted object. Mines are intended to destroy of damage vehicles, aircrafts or vessels, or to injure, kill or otherwise putting staff out of action. It is also possible to deny enemy access of a specific area by laying mines.

- Paratroopers

- Airborne Division. Military specialized in parachute landings.

Images

Military Training (Miami Beach/Panama City, Florida)

My assignment was to the Army Air Force with basic training to be at Miami Beach, Florida. What a training base! Our barracks were the hotels on the strip, our parade and training grounds were the swank golf courses. My barracks was in The Mansion. At that time The Mansion was one of the more elegant hotels on the strip. We were quartered three to a room under the most pleasant circumstances. We were required to make our own beds and keep the rooms military neat.

Training in Miami Beach was rather uneventful. We were marched and marched up the streets, down the streets, across golf courses – everywhere it was “Left, Right, Left, Right” – on and on. Tests were given on every subject known. If you were fluent in French or German you were sent to the West Coast to fight the Japs. This was military efficiency at its best. If a piece of clothing fit, it was evident you had been given the wrong size. “Hurry up and wait” the military way of doing things. You always had to wait, wait. Finally I received my military assignment. Report to Army Air Force Gunnery School, Tyndall Army Air Base, Panama City, Florida. Reporting to Tyndall around the first of November, 1942, my training was to get underway.

Naturally, it was more hurry up and wait, left, right, left, right – then at long last practice with guns and live ammunition. The training at Tyndall was vigorous. Our physical ed. Officer was Hank Greenberg, later to be inducted into baseball Hall of Fame. At Tyndall the new recruits were joined by several old regulars. They were Staff and Tech Sergeants who would assist our training. Also they would become aerial gunners.

These old regulars, to the man, said our training, obstacles courses, etc., were tougher than anything they had faced. Time had erased the names of these men, except there was one named Cleo Grossman, from Upper Sandusky, Ohio that remains with me. On the gunnery range Cleo and I stood head and shoulders above the rest. Frankly, we were better than the old regulars. So many of our buddies were from New York, Chicago, and the other large cities. To them a rifle, shotgun, or machine gun was a foreign instrument. When we would go to the gunnery ranges, it would be Cleo and I who did the shooting. We would be given several cases of shells that had to be fired before we could leave the gunnery range. Often I would shoot my rations up, also boxes and boxes for the other fellows. I recall one young boy who had shot a shotgun from the hip. His hip was black, red and blue, so was his shoulder. The entire left side of his body looked as if he had been hit by a car. He bought me several beers for shooting up his ratio or shells.

Clark Gable, undisputed King of the Movies, was in our class. Since we were seated in alphabetical order, he and I would sit across from each other in the classes. He was an excellent shot with all guns. (After the war I read in the paper where he was caught with over 200 ducks in his possession).

My oldest brother, Jimmy, came to Panama City to visit me. I was given a pass to visit with him in town. While we were eating dinner Jimmy said,

“Brother, I would have sworn I saw Clark Gable in the lobby of my hotel.”

I told him he probably did since Gable was in our class. Jimmy said he had a woman on each arm and they were crawling all over him. Clark Gable did not finish in our class. He was called out on special assignment probably to make a propaganda film.

One of our top instructors was a sergeant, Rufus Raby, from Athens, Alabama, not too far from my home town of Fulton, Mississippi. We got along fine, on and off duty. He told me that I would be the butt of his jokes since these “damn Yankees” would get upset if he used their names. Frankly, we all looked forward to his classes and gun instruction. An unusual incident happened to me during one of our trips to the gunnery ranges. I had easily shot up all of my shotgun shells, therefore, the Sergeant had me loading the clay pigeons for others to shoot. I was in a little dugout affair loading pigeons, when one of the others tripped the device that threw the pigeons. The timing was perfect, I bent over to load when the arm came around to throw the pigeons, hitting me across the bridge of my nose. The blow was similar to being hit across the nose with a iron as used by John Daly. Sticking my head above the dugout, bloody face with blood spewing out in a stream, screaming.

“What are you sons-a-bitches doing? Trying to kill me?”

Someone shouted to the sergeant that someone had shot Gibbs in the face. (My sergeant buddy told me later that he could feel the sergeants stripes being pulled from his uniform). I was rushed back to the base hospital where the emergency crew was waiting. After the doctor examined me I was given pain shots, a few stitches in my nose, and told to take the rest of the day off (this was about 3:30 P.M.). The sergeant loaded me down with beer that night since one of the new recruits said he had stumbled hitting the release button that controlled the pigeon thrower. No action was taken against the sergeant.

Finally, graduation day – gunners wings, staff sergeant stripes, and further assignment. Hurry up and wait. Finally, my orders. Several of my buddies and I were to report to Armament School, Lowry Army Air Base in Denver, Colorado. Most of our gunnery class went to Denver.

We hadn’t been paid for almost two months and everyone was broke. I called home and told mother and dad what was happening. Dad immediately wired me $100 via the Red Cross, (a princely sum in 1942). By the time I quit loaning, $5 here, $3, or whatever, my bank roll was sinking fast.

We were loaded on wooden Pullmans, relics of World War I, for our trip to Denver. After numerous delays we reached St. Louis, Missouri, on Christmas Eve. There was a retired Major recalled from World War I who was in charge of the trains. He was an older man, no doubt too old for combat duty, but a very nice fellow. When the train stopped on a siding in St. Louis, across from us about 500 yards was a large liquor store that was open. Since I still had a few dollars, the troops elected me to approach the Major about running over to the store for some spirits. The Major’s reply was,

“This is a troop train. No one is to leave the train under any circumstances nor are spirits of any kind permitted on troop trains. The fact that tomorrow is Christmas makes no difference.”

There were several troops around when the Major walked by where I was seated with a couple of buddies. He stated,

“Sergeant Gibbs, I have to go the front of the train for about 20 or 30 minutes, no more than 30.”

He went through one door, three of us went out the other end of the train. In less than 15 minutes we were back on the train with about 4/5 cases of beer and a few bottles of spirits. The major had a very big glass of bourbon with 3/4 beers in his compartment when the train rolled out of St. Louis.

The next day, Christmas, we had a big spread aboard the train, turkey and dressing with all the trimmings. Yet, no man aboard could get the Christmas spirit, for we all knew we were heading into the war, we were a long way from home, and no way to make contact.

Definitielijst

- machine gun

- Machine gun, an automatic heavy quick firearm.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

Lowry Army Air Base (Denver, Colorado)

When we arrived in Denver there was 6/8 inches of snow on the ground and more coming down, quite a change from Florida. We fell in outside the troop train where we were greeted by an old regular sergeant. His comments were along these lines,

“Denver is a serviceman’s city, the people here are super, the city is super and if any of you creeps screw it up, I will personally pull your stripes and kick ass from downtown to the guard house.”

The sergeant was correct. Denver was a super place for any service man.

Training here was tough, 4 miles double-time before a bite of breakfast, then double-time to the latrines, classes, or whatever. We had to double-time in that high altitude – tough! We were schooled in field striping 30 and 50 caliber machine guns, 20 and 30 millimeter cannons, plus rifles and other weaponry.

Since we arrived about 2 or 3 days before New Year’s, everyone was given a 48 hour pass prior to starting actual schooling. Two friends; Victor Florence (a few years older than the rest of us) and Frank LaPorta, and I headed for Denver broke but happy. We probably didn’t have $5 between us. Knowing we would need $.50 a piece to return to base, we were not prepared to splurge. Vic and Frank were from the Boston area, yet the three of us seemed to hit it off on all fours.

We hit downtown Denver on New Years Eve at about 8:00 p.m. We were standing on a busy street corner when a car pulled up with 3 young ladies who started hollering at us to, “Get in”. I immediately ran to the car, told them we were flat broke and needed to head back to the base. Their response was immediate,

“We have the money. Don’t worry we will return you to the base sometime.”

Three airmen had just struck gold! Amelia, the older of the ladies about 26/28 years old and owner of the car, and Vic were married about 2 months later. Neither Frank nor I had matrimony on our minds. For the 6 weeks we were in Denver, the six of us were rather constant companions. Since the girls had excellent jobs they often had to pick up the bills. Once our military pay was received, it was blown on the absolute necessities – beer, spirits, and cigarettes.

Denver was a super city for service personnel. When Vic, Frank, and I would hit town before the ladies were off from work we would head for the bar at the Brown hotel (that may not be the correct name, but it was something similar). This was one of the grand hotels of the west. Ranchers, oilmen, etc., always met there. Whenever the 3 or 4 of us would enter the bar, some rancher or others would invite us to join them. We would always accommodate.

One incident I remember from Denver was when I hit town a few hours before Vic and Frank. There was an Italian bar that we often frequented, so I had left word for them to meet me at Geno’s. Since Vic spoke fluent Italian and Frank some, the owner took a liking to us often furnishing freebies. Since I was alone, there were four girls, 20/25 years of age at a table, who waved me over to join them. Naturally, I did in a hurry, especially since the girls were very attractive, well dressed, and evidently had ample funds to spend. In a short time it was determined that one of the girls had her own plane, ample gas, and money to spend (apparently her family must have been very wealthy). The plane owner found out I had a pilot’s license, therefore, she and I made immediate plans to meet the following weekend for an out of town trip. The other 3 girls were pulling on my sleeve, saying I had to stay with them. My ego was flying high.

Sometime during this planning, Vic and Frank arrived at Geno’s. I waved to them since they had stopped to talk to Geno and apparently were looking for me. Vic walked over to our table, took me by the arm, saying,

“We have to report to the base immediately. Right now!”

I gave my new loves a fond farewell – the brave airman leaving for battle.

Once outside Geno’s, Vic and Frank starting screaming and laughing,

“Gibbs, Geno told us those gals were 100% lesbians.”

My ego was deflated and about the only thing I could say was,

“We didn’t have those in Fulton, Mississippi.”

As with all training phases, our schooling at Denver was soon over. Again, you parted from old buddies, soon to make new ones. Vic, Frank and I had been together longer than most, yet when we parted at Denver I would never see Frank again. Vic stayed on in Denver for a few weeks after I left. He and Amelia were married while he was there. Our paths would cross again.

Most of us were sent from Denver to the Replacement Depot at Salt Lake City, Utah.

Definitielijst

- caliber

- The inner diameter of the barrel of a gun, measured at the muzzle. The length of the barrel is often indicated by the number of calibers. This means the barrel of the 15/24 cannon is 24 by 15 cm long.

Replacement Depot (Salt Lake City, Utah)

My stay in Salt Lake City was rather brief. No trips to town while we were there. Once in Salt Lake we were to be shuffled around to various Air Bases for crew assignments. There were two incidents that are remembered from Salt Lake.

We were all called out to stand at attention while a sergeant was drummed out of the service. The drums solely rolled, the stripes clipped from the sergeant’s sleeves, his buttons pulled, and the man was escorted to the gate where he was told to never again set foot on a U.S. Military installation. It looked like a full scale Hollywood Production. Fifty years later, I still believe it was staged.

About the third day we were in Salt Lake I was told to report to the commanding officer on-the-double. Thinking about the sergeant that had been “drummed out” the day before, my previous military escapades were rushing through my mind when reporting to the CO. The conversation went something like this,

“Sergeant Gibbs your record indicates you have a pilot’s license, is this correct?”

“Yes, Sir.”

“Why didn’t you go into cadets?”

As so often, the entire story about the heart murmur was repeated. The CO commented that the service must be good for my hearts since there was nothing in my records to show anything but a healthy staff sergeant. Regardless, all that I needed to do was sign on the dotted line and it would be on to Cadet School. For reasons that have never been understood I asked permission to sleep overnight on this subject. This was agreeable with the CO. He complimented me on wanting to think about it.

Returning to the barracks the subject was discussed with several of the fellows. They were 100% opposed to me leaving the group. The comments running, “The war will be over before you finish training.” “We need to stay together”, etc. Early the next day I reported to the CO telling him the cadet training was being declined. The CO stated he thought it was a mistake on my part, yet, it was my decision. Apparently that decision made over 52 years was the correct one since I survived the war. No doubt there were many who entered cadet training about the same time as I would have who are no longer with us.

Shortly after the cadet episode, I was on my way to Davis-Monthan in Tucson, Arizona. Very few of those who had advised me not to become a cadet were sent to Davis-Monthan.

Davis Monthan Air Force Base (Tucson, Arizona)

When the Air Force became a separate branch of service eludes me. Yet the Air Force did break away from the Army to become an equal to the other branches of service. Therefore, from now on I will refer to Air Force rather than Army Air Force.

At Davis-Monthan the Mess Sergeant, or one of the cooks, was from the deep south for cornbread was a regular at the mess hall. It was a regular for me with all food while many of the Yankees would always ask, “What is that stuff?”

While stationed at Davis-Monthan it was military as usual – hurry up and wait.

Waiting to be assigned to a crew, I went into Tucson and to the fair grounds where a nice fair was in progress. (At this time “zoot suitors” usually Hispanics, were known to gang up on servicemen and beat them severely. It always happened when one or two service men were away from the others. The beatings would take place for no reason.) While on the fair grounds I noticed two of the “zoot suitors” roughing up a young girl. With a total lack of common sense I stepped into the fray pushing one of the “zooters” away, telling them to leave her alone. (At that time my physical being was probably the best of my life, which probably couldn’t be said about my brains.) Regardless, in just a few minutes it was most evident that every move I made was being followed by 2 or 3 “zooters”. Then their number started increasing. Fortunately for me, a couple of MP’s happened to appear on the fair grounds. I immediately went to them and told them what had happened. They suggested that they escort me back to the base. That was most agreeable with me. Prior to heading back to the Air Base, the MP’s reported what had happened to their headquarters. They were told to bring the Sergeant by MP headquarters. Once at MP Headquarters I was ushered into the CO’s office. The Major in charge, an old Army regular, asked me to help him with the “Zoot Suit” problem. My answer was that I was due back at the base and would be AWOL in less than an hour. The Major said he would take care of all such problems. The plan was simple. The MP’s would return me to the fair grounds, the “zoot suitors” would spot me immediately and once the “zooters” made their move, the MP’s would move. My comment was,

“Major, these guys have knives, brass knuckles, whips, etc. Are you sure they won’t have me cut up before your men can get to me?”

After many assurances from the Major, the plan was put into operation. MP’s were dressed in all sorts of clothing. I was deposited at the fair grounds and as expected the “zooters” soon spotted me. In a matter of minutes, “zooters”, five, six, and more were making a circle around me. Then the MP’s moved in – big husky lads swinging heavy billy clubs with gusto. They did part some hair and break faces. Ambulances hauled the “zooters” to jail. On the return trip to MP Headquarters, the MP’s in my jeep were patting me on the back, laughing, and talking about who knocked out the most teeth. The Major was elated, assuring me my CO would be fully informed of my absence. He had a jeep to return me to my barracks. What a night!

The next morning, bright and early, “Gibbs report to the CO.” Upon reporting, the CO was grinning with a comment,

“Seems that you had an interesting night. Major Dunn sends his compliments for your help. I add mine. You need to take the day off.”

My comment was, “Thank you, Sir. The fair grounds will be avoided.”

Shortly after this escapade I was assigned to a crew. Our pilot’s name was Turner, a super guy who could fly a B-24 backwards. The co-pilot was named Williamson from Fort Smith, Arkansas. Most of the other’s names escape me, yet I can still remember the names of two of them; Earl Schleibaum, a gunner, was from Indiana; and the tail gunner, Herb Garrow, was from Niagara Falls, NY. The Niagara Falls part remains with me because he was always talking about his home town. At that time Niagara Falls was the honeymoon capital of the world. With our crew now assembled, we started the serious business of becoming a team. This was good crew, we worked together as a unit. In due time we completed Phase I of our training then transferred to Biggs Air Force Base, El Paso, Texas.

Definitielijst

- mine

- An object filled with explosives, equipped with detonator which is activated by either remote control or by colliding with the targeted object. Mines are intended to destroy of damage vehicles, aircrafts or vessels, or to injure, kill or otherwise putting staff out of action. It is also possible to deny enemy access of a specific area by laying mines.

Images

Biggs Air Force Base (El Paso, Texas)

While at Biggs AFB we completed the second phase of our training and were well into the third phase of training when I was injured in an accident. Somehow the tail gunner, Herbert Garrow, the man from Niagara Falls, had the gun site lowered over him trapping him in his turret. Fortunately or unfortunately, as the case may be, I was in the waist section visiting (the nose turret was rarely used during low level practice sessions). Since it was evident there was something amiss in the tail turret, I walked back there, saw the predicament, opened the turret door, reached in to hit the button to raise the gun site, when unfortunately the plane made a sharp turn to make another bomb run. This turn caused the gunner’s body to move, hitting the hydraulic system that turned the turret. The turning of the turret pinned me between the turret and the side of the plane. I could feel the bone in my left clavicle breaking. Fortunately, the plane turned to a level position and the tail gunner was able to shift his weight there by righting the turret and releasing me. Otherwise, the hydraulic pressure could have just about cut me in half. The pilot was notified of my injury, therefore, we immediately returned to Biggs. An ambulance was waiting on the runway to rush me to the hospital. Arriving at the base hospital, it was again, hurry up and wait. Hurting from head to toe it seemed like hours, probably no more than 30-40 minutes, when a doctor walked through the room. He asked me what I was doing in the emergency room. I told him. The doctor looked at me and asked,

“Are you the airman that was hurt in the plane accident?”

“Yes, Sir.”

“What have they done for you?”

“Nothing!

All hell broke loose. The doctor was raising hell at everyone, nurses, aides, everyone in sight. Here was a man not hurt in a car wreck, drunken brawl, venereal diseases, or like most of their patients goofing off, and he sits in the ER suffering with nothing being done. The span of attention being given me changed from nothing to everything, nurses, medics, etc., etc., whatever and fast. These events happened May 29, 1943. On June 6, 1944 (D-Day) I would be released from William Beaumont General Hospital, El Paso, Texas. For 53 weeks, I would become a well-known person in the medical sections of Biggs AFB Hospital and William Beaumont General Hospital. Over a half century later, I often reflect and wonder how much experimenting was done on me. It was a well-known fact that medical science made tremendous strides during WW II. In all frankness it can be said the treatment and consideration given me at all times (except first hour in ER) was super. Doctors, nurses, (especially 3 or 4) medics and staff brought me through with flying colors. After being admitted to the Base Hospital the usual series of tests, X-Rays, etc. were run. Within 48 hours I was informed that my left clavicle was crushed to the extent that to repair it surgery would be required. The medical team had previously inquired if this particular bone had given me previous problems. My answer was that during high school the bone had been broken 3-4 times, usually playing football or some other contact sport. A few months later I was told that this particular bone had lost all marrow, therefore unable to help itself in the healing process. A new bone would be built.

Within a very few days after entering the hospital at Biggs, a surgical procedure was performed on the left clavicle. This surgery was a process where the bone was wired together. Within a short time it was evident the procedure did not take.

While at Biggs hospital, a very attractive nurse, Pennsylvania Dutch, (can’t remember her name) and I became dear friends. Dad came to visit me between surgical procedures. He met the nurses, later commented to me “that she was some looker – are you contemplating marriage?” I assured Dad that matrimony was not in my immediate plans. This little cutie was transferred shortly after Dad’s visit. She was replaced by a former Navy nurse, also Pennsylvania Dutch. We struck up an immediate friendship.

Also, while at Biggs, the hospital Mess Sergeant and I struck up a fine friendship. He was from Sullivan’s Hollow, Mississippi, yet everyone called him “Bama”. He didn’t know why this name was tacked on him. Since we were from Mississippi it was easy for Bama to have food prepared in the deep south manner. Often Bama and I would enjoy a good steak at 3 p.m. or 3 a.m. or whenever. Bama went with the nurse in charge of the pharmacy, therefore, we were well supplied with spirits. If the pharmacy would run low, Bama would chop off a few steaks, liberate 10-20 pounds of sugar, go to town and return amply supplied with our needs. Mess sergeants and supply sergeants were the only ones who really enjoyed the war. No doubt the officers in charge of these departments, also had a wonderful war.

After an appropriate recuperative period it was back to surgery for me. This time a metal plate was inserted into the bone. In short order the incision was swollen to the size of goose egg. The incision would be opened for drainage every few days. In a couple or three weeks the medical staff informed me the plate did not take, further surgical procedure would be needed. The Biggs surgeon told me that as soon as possible they would have me transferred to William Beaumont General Hospital where a full orthopaedic team was available with the most modern and up-to-date equipment available. William Beaumont was just a few miles from Biggs AFB.

Within a short time the transfer was made to William Beaumont, where an orthopaedic surgeon, William Basom, took a personal interest in my case. In effect he said,

“Gibbs, I am going to correct your problem.” In time he did.

As with any hospital it was tests, tests, X-rays, and more X-rays. After every test known to man, Dr. Basom told me of the procedure he was going to use to correct the damaged clavicle. He would remove a big piece of my left shin bone, using this bone to make a new clavicle bone.

“The old bone won’t heal, so we will make you a new one.”

With this procedure I was told that it would be most confining for me for several weeks, a crippled leg and clavicle. It was indeed confining for a considerable length of time. The surgical procedure was performed shortly after Thanksgiving, 1943. I was placed in a room with another Mississippian, J.C. Lee, from Brooklyn, Mississippi. JC had a bone problem that was incurable, therefore, he was discharged in early 1944. We would later meet at Ole Miss in the spring of 1946.

Due to the way my surgery was treated, left leg held with pulleys and weights, left clavicle strapped down, totally immovable, it was necessary that I be kept in a semi-private room for an extended period of time. Since I would be in this position over the Christmas holidays, one of the little nurses was kind enough to smuggle some Christmas spirits to my room. One cutie bounced into my room stating for a Christmas present she was replacing the male aide and would give me a bath to remember. Did I ever look forward to Christmas morning! She backed out at the last minute citing being caught and facing court martial.

Fort Bliss, on old Calvary Fort located in El Paso, was a few miles from William Beaumont and often had old calvary men in the hospital (many of these troopers had been in Army 20-30 years, still buck privates. I remember one commenting that he had made corporal at one time, but it was just too damn much responsibility). One of the old calvary men, a 16 year veteran, had been kicked in the back by his horse. Infection set in the wound and he went from 180 pounds down to about 85 pounds. The doctors had tried everything they could to no avail. I think it was Dr. Basom who decided to try the new drug, penicillin, on him. About 3 months later, he was on his way home to Georgia, weighing 140 pounds.

Another case of interest was a young GI who had gasoline exploded in his face. He didn’t have a hair on his face, two little peep holes for eyes, two for a nose and a mouth a bit larger than a grape. It was difficult to sit with him and eat, yet several of us would. He was fortunate that one of Hollywood’s top plastic surgeons was at Beaumont. By the time I left the hospital this young man was starting to look really good.

Shortly after New Year’s, Dr. Basom had a contraption made for me. It was in the form of a cross with my shoulders strapped back so there was no movement. With this rig on and a cane it was now possible to move about the hospital and the beautiful grounds. On the grounds there was one young fellow always fishing over a dry creek bed. He was fishing for a Section 8 Discharge (mental). He hadn’t obtained this discharge when I left the hospital in June 1944.

The healing process was too slow for everyone. The decision was made that since I had an infected wisdom tooth that this in turn was slowing the other healing process. So all my teeth were pulled (halfway through this procedure the dentist doing the pulling told me this was so long and perfectly shaped, he ran down the hall showing the tooth to the other dentists. He and I strained for that tooth to be pulled. The tooth seemed to give way half way up my face). One night after this happened, I started haemorrhaging from my mouth. There was just no stopping the flow of blood. Finally, along about midnight, a surgeon was called to my room. He placed several stitches in my mouth. The surgeon for some reason was unable to use any shots in my mouth, but did have me knocked out as soon as the bleeding stopped. A nurse was assigned to my room for the rest of the night.

During my recuperation, a friend of mine at Biggs (his name escapes me) in the payroll department, found a regulation whereby since I was hurt while flying, my flight pay should have continued. He brought me a very nice sum of money representing my back flight pay. My friend was a big, 6’4”, 225 lbs., red-faced Irishman who enjoyed his little nip, or two, or ten. I assured him that as soon as possible we would go to Juarez, Mexico (just across the Rio Grande from El Paso) and celebrate my new found wealth. Most of my new found wealth was soon squandered on perfume, candy etc.

After several weeks of being strapped, the cross was removed. I could walk without a crutch and was permitted to go to town with some of the fellows. Life was looking much better.

My big Irish buddy picked me up and with the doctor’s okay we headed to Juarez. This was a big mistake! We were in one of the frequented bars when all hell broke loose. I was wearing my arm in a sling, therefore sitting in the back of the bar visiting with some senoritas, when the fight broke out. Apparently my big Irish buddy had words with some Mexicans, the net result being he was using a chair, table, or whatever to whip upon several. The bar was soon filled with Mexican police, in short order we were escorted to Juarez jail (the jail had a dirt floor) and locked up for a couple of hours. After cooling our heels we were brought to a room in the front of the jail and fined every penny we had except enough money for bus fare back to Beaumont.

Within 2 – 3 weeks off our Juarez episode an American Colonel was almost beaten to death by the Mexican police. Juarez was placed off-limits to all American Service personnel. It took some doing between Washington and Mexico City to resolve the problem. American MP’s were permitted to walk the streets of Juarez with clubs, but no guns. This might have been the policy for the duration of the war.

In April ’44, I was given a 30-day leave to go home. The only transportation was by bus, old buses. The one I was riding broke down in the barren plains of West Texas in about the most remote area of the state. We spent half a day in an area that snakes had abandoned. Even with such a bad start the month at home was glorious. Eating Mother’s cooking, sleeping in my own bedroom, no duty to perform, over to Ole Miss in Dad’s Caddy; life was beautiful yet it had to come to an end.

On my return to William Beaumont, Dr. Basom told me he would release me to return to military duty in a short time. One June 5, 1944 I was informed that I would be returned to Biggs AFB the next day. It was only fitting, another night in El Paso prior to a return to active duty. I told my friend in the hospital ward that Ike could now open the second front since Gibbs would now be able to help him. At about 2-3 a.m. when I returned to the ward, everyone was gathered around the radio listening to the news. Someone yelled to me,

“Gibbs, Ike got the news about your returning to duty, he has opened her up.”

In all modesty it was probably just a coincidence. Returning to Biggs on June 6, 1944, most of the guys I had known were gone. All the nurses from the hospital had been shipped out, most overseas. Bama and my buddy in payroll transferred to other bases. I have never seen any of them since the early part of 1944.

Upon my return to my old squadron, an immediate interview was with the flight surgeon, Major Swartz. His first comments were,

“Glad to see you up and around. We will find you a nice desk job for the duration. Are you interested in any particular department?”

My response was, “Major, this damn war has treated me badly. I need to get even with someone. Please Sir, put me back on a flight crew. The doctors have given me a clean bill of health.

The major commented along these lines,

“Are you sure no brain damage was done. If you feel this strongly about being back on a crew, I will place you on one in the third phase of training.”

My response was, “Thank you, sir!”

Within a week or two I was assigned to a crew in the final phase of training. In a short time, radio op Jack Naifeh, gunners C.D. Chinberg and Robert Croom, and I became good friends. Naifeh and I were constant running buddies. Our pilot’s name was Cook, a Texan, who could give everyone a case of RA by just being around him. The others of this crew were Carpenter, Corces, Maroney, Draper, and Oliver. We finished training at Biggs AFB, given a weeks leave to go home with orders to report to Topeka, Kansas on a certain date. The only excuse for not being at Topeka would death – OURS! We were given high priorities, therefore any space available on military or civilian plane to Memphis, Tennessee.

The family met me and for the next few days we would be together constantly. On the day Jimmy and Dad were to carry me back to Memphis for a flight to Topeka, Mother and Dad asked was there anything I needed or wanted prior to leaving home. I mentioned a beautiful wrist watch in Brasfield’s Jewerly store in Tupelo. It was Sunday. Dad immediately called H.K. Brasfield, an old friend. Brasfield told Dad he would be waiting for us. It was difficult to leave my mother and sister, they had tears in their eyes. My tears were in my heart. We stopped in Tupelo, picked up the watch (this watch was taken from me when we were captured by the Germans) and on to Memphis. At the airport, men don’t cry, so Dad, Jimmy, and I gave each other a big hug prior to my heading out the gate. Others nearby were giving me the high sign, patting my back or arm saying such as “Give them hell”, “Good luck, Sergeant”, etc. It was a warm, yet lonesome feeling.

Arriving in Topeka, our crew was reassembled for the hurry up and wait period. Shortly after arriving in Topeka we were told that our plane delivery would be a few days late. We were given 24 hour passes with instructions that one minute late returning would be considered desertion.

Some of the locals told us that Kansas City was a dream city. Since there was a stream liner train running through Topeka to Kansas City, Naifeh and I hit the train running. Arriving in KC it was soon evident that KC was indeed a service man’s city, girls, girls everywhere with few men in uniforms. We headed for the Mulenbach Hotel, one of the distinguished hotels in Mid-America. Naifeh and I were picked up within an hour by two lovely young ladies. They became more lovely and beautiful when it was determined that Naifeh’s girlfriend’s father owned a big liquor store. (Before we left KC she had gone to her father’s store, gone under the counter bringing out some fine products, loading us down for our return trip to Topeka.) That night, while we were at a night club, our friends went to the ladie’s powder room. Near us was a table with 3-4 girls. They came over to our table asking us to dump the two bags we were with and join them. These girls were real dandies, yet Naifeh and I thinking of the liquor store, had to reluctantly decline.

The following day we returned to Topeka only to be told of further delays in plane delivery. Back to KC for us with more goodies from the liquor store. When we returned to Topeka the next day with another couple of sacks of spirits the MP’s at the gate kept asking where were we getting all the good stuff. Our response was rather vague. We made plans to return to KC for a third time, but suddenly all passes were cancelled, everyone confined to base. The planes were being delivered. We had our plane! In a short time, orders were cut for our departure. OUR plane was loaded with our gear, spirits, and whatever. Everyone had various suggestions for a name for the new beautiful B-24. Little did we know that this was not our plane.

The big moment finally arrived. From Topeka, we flew to Bangor, Maine. From there to Gander, New Foundland, then to Goose Bay, Labrador, on to Reykjavik, Iceland. At each stop we would re-fuel, have the plane checked thoroughly, try to get a night’s rest and a couple of good meals. The good meals were questionable. From Reykjavik, Iceland to Wales where our plane was turned over to the Air Force. We had in reality ferried the plane to the war zone.

More hurry up and wait were the orders. We were sent to Newcastle, County Down, North Ireland for more training and indoctrination. Mostly indoctrination. We were told in very stern terms we were not to act like the over paid, over sexed American Servicemen. Behave!

While we were in North Ireland there was very little work with passes to town every day. Nowhere were the people as friendly as the Irish. The pubs had plenty of stout and ale, fish and chips were the staple food and the Colleens were as pretty as one would expect. I was indeed fortunate, twins, one worked at night, the other during the day. It was tough duty, yet being in the best of health, the courtship of twins was carried out with vigor. Eileen and Kathaleen Hallahan were pretty, buxom, red-headed lassies who made me the envy of our group. Newcastle was a picturesque little town on the coast with a small pavilion down by the beach. Every afternoon there was a small band of old men who would perform, playing all the old Irish melodies. This was the gathering spot for just about everyone, the locals and GI’s. One afternoon after we had been in Newcastle a week or so, there were several of us down near the pavilion enjoying our stout. Mrs. Hallahan was in our group, when one of my buddies said,

“Mrs. Hallahan, Gibbs is probably going to marry one of your daughters. We are wondering which one.”

Her reply was, “Sgt. Gibbs is welcome to marry either.”

Later back at the base while everyone was laughing and I was questioning their ancestry, it was made as clear as possible that this soldier was not interested in matrimony. This seemed to come up everywhere I was stationed.

It would be a safe statement to say our stay in North Ireland was enjoyed by all. We hated to see it come to an end.

Definitielijst

- D-Day

- The day of the long awaited invasion of western Europe in Normandy, France, 6 June 1944. After a long campaign of deception the allies attacked the coast of Normandy on five beaches to begin their march on Nazi Germany. Often explained as Decision Day, though this is entirely correct. The D stands for Day as generally used in military language. In this case it means an operation beginning on day D at hour H. Hence “Jour J“ in French.

- indoctrination

- The education or brainwashing of people, sometimes by force, to accept a certain opinion or political doctrine. This doctrine is to be followed henceforth without question.

- Mid

- Military intelligence service.

- mine

- An object filled with explosives, equipped with detonator which is activated by either remote control or by colliding with the targeted object. Mines are intended to destroy of damage vehicles, aircrafts or vessels, or to injure, kill or otherwise putting staff out of action. It is also possible to deny enemy access of a specific area by laying mines.

- second front

- During World War 2 the name of the front that the American and Brits would open in the West to relieve the first Russian front.

- squadron

- A military unit in the Belgian navy usually six to eight small ships operating together under one command. The smallest military unit in the Dutch air force of about 350 men. In most countries is the designation of a military unit thesize of a company. It is either an independent unit, such as a battery, or part of a bigger Calvary unit. In the air force it is the designation of a unit of aircrafts.

Images

To England and the war

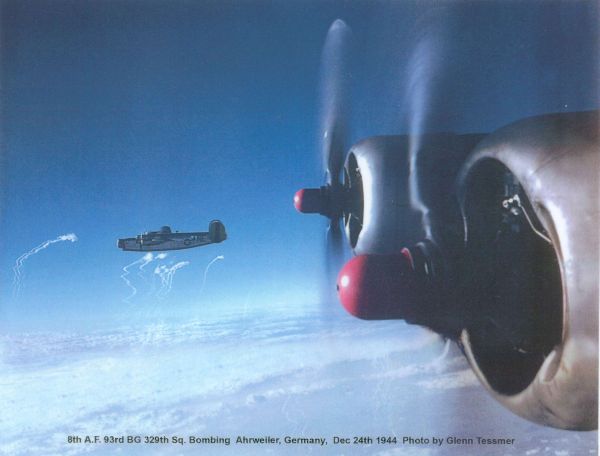

Leaving North Ireland we were sent directly to the 93rd Bomb Group just outside of Hardwick England. After two years in the service, I was now in the war. We were assigned to the 330th Bomb Squadron. Before being shot down on January 28, 1945, I also served in the 328th and 329th Bomb squadrons. Again, hurry up and wait, more training, going to gunnery range in Scotland was to be the program for several days.

Arriving at the 93rd, Naifeh and I wandered over to NCO Club. Looking at the lists of men who signed in there, two names grabbed me in an almost scarey fashion, HERBERT GARROW, Niagara Falls, New York and EARL SCHLEIBAUM, RFD #1, Seymour, Indiana. Pointing to their names, my comments were along these lines,

“Naifeh, these were my running buddies on my first crew.”

Since my letters to them had been returned, marked MIA, it gave me an odd feeling. After over a year I am assigned to the same BG and squadron as my first crew.

Leaving the club we were walking across a ball field when, lo and behold, we meet my old co-pilot, Williamson from Fort Smith, Arkansas. He was as surprised as I. The first expressions,

“Gibbs what the hell are you doing over here?”

My explanation followed with the question,

“What happened to Turner and the crew?”

Williamson, a Second Lt. the last time I saw him, was now a Captain. He told me that when the crew arrived at the 93rd, within a couple of months, Turner was made a lead pilot, and he and the navigator were pulled from the crew to make up another crew with himself as first pilot. The arrangement was beautiful yet on a mission crossing into France, Turner was hit in the bomb bay by flak. The plane exploded with only one man getting out of the plane. Somehow the engineer managed to get of of the plane, probably blown out, unfortunately Williamson was flying off Turner’s wing, the engineer hit his wing, cutting him in two.

Williamson said “Gibbs, I hate to tell you they were all killed.”

My first day in ENGLAND was a sad one indeed.

Shortly after this incident the 330th sustained heavy losses, so heavy that Williamson was promoted to Major and made CO of the 330th for a short time. Promotions came fast in those days.

During the first couple of weeks in the 93rd, Naifeh, Croom, and I tried to drink the island dry of stout. We didn’t, but did keep the breweries working over time. Chinberg would sip on one or two, always leading us back to Quonset Hut. If we were on a short pass to town, he was sure to get us back to base.

The officers and NCO’s who had completed their tours were constantly saying – “you guys are lucky, nothing but milk runs.” For this group, most of their flights were just that – milk runs (an expression for easy flight with no flak or fighters.) These crews had made most of their flights over France or other occupied countries, therefore some of the crews hadn’t seen enough flak to count. The reason for the absence of flak and fighters was that Germany had pulled all their guns and planes back into Germany to protect the Fatherland. Every flight I made was over Germany with fighter planes rarely seen, but often flak so thick it didn’t appear possible for a big bomber to fly through it. The absence of German fighters was due to B-24’s fire power, tight formations and our “Little Friends” (long range U.S. fighter planes.)

The big day arrived! Report to briefing. The first few briefings may have had a touch of excitement or romanticism involved but in a short time, after seeing B-24’s spiral out of control, the “report to briefing” had a sinister almost deathly sound to it.

Unfortunately I do not remember when we flew our first mission. Reiterating, all flights I made were to targets in Germany. Shortly after we crossed the Zuider Zee, I called out,

“Flak at 2 o’clock”.

Everything stretching their necks, “Where!”, “Where!”

Damn it – 2 o’clock!.”

There it was, our first encounter with the horror of the air. The first mission, as all air force missions, was a success (to all crews a successful mission was one where you made it back to the base in England.)

Our sixth mission was a holy horror – the sub pens in Hamburg. On the morning of the briefing we were told that when we headed into our bomb run there would be over 600 guns trained on us. Tears appeared in many eyes, no doubt urine in several flight suits. We circled to the west of Hamburg, climbed as high as possible, turning on the bomb run, the 24’s noses were eased down a bit going as fast as possible. With a 90mph tail wind we unloaded the largest load of explosives ever known to man. Many B-24’s went down in the raid including some with buddies aboard. When we returned to base, it was on to the debriefing and a double shot of bourbon. Some of the crew was too upset or disturbed to use their bourbon, therefore Croom, Naifeh, and I had to gladly assist. After several hours on oxygen and about 3 double bourbons, you could almost flay your arms and fly.

Three day passes to London for needed R and R (rest and relaxation). As with all GI’s we headed for Piccadilly, the center of the clubs, pubs, and shops. Amazingly, Naifeh and I for the first two days enjoyed the cultural aspects of London, Westminster Abbey, St. Paul’s Cathedral, and tours around the old city. We also took time to visit several of the pubs and clubs. Our last night on this visit I met a real cute little WAF (Women’s Auxiliary Force). She was a charmer that all the fellows liked. Our beloved pilot, Cook, tried to cut in on me with the WAF. He didn’t succeed. We made appropriate plans for my next visit to London.

Back to the 93rd and more tough missions in store. About this time our group led an attack on Kassel. This mission was a success as far as our crew was concerned, yet it was a disaster for the 93rd. We did lose some planes on that raid. My turret and oxygen tank was knocked out by flak.

Shortly after Kassel our crew was split up. I have been told our co-pilot was the leader causing the split. To this day no one has told me precisely what happened. Regardless, I was now a free lance nose gunner with no crew. The orphan was left to fend for himself. Until I was assigned to the Rosacker crew, my number would come up only when a crew needed a nose gunner.

One mission stands out that just about dealt me and a squadron a very bad hand. I was sleeping soundly and the CQ, (Charge of Quarters) shook me awake.

“Gibbs got a milk run for you, nose gunner on the crew sustained some burns.”

I told the CQ that I had flown a day or two before, also had a big 3 day pass to see my WAF in London. The CQ was insistent.

“Sure help you get your numbers in and back home. Man, it’s a milk run.”

With reluctance, I volunteered to go out (never again). A jeep picked me up, I rushed to briefing room, the crews had departed for their planes. Upon my arrival at the briefing room one of the fellows I knew told me the gunner had really poured lighter fluid on himself and set it ablaze, claiming it was an accident. My comment were that the CQ told me it was a milk run. My buddy said, “Milk run my ass, look at the map.” The mission was to the very middle of Germany! I was rushed out to the flight stand where a very young inexperienced crew was waiting (I believe this was their second mission). The crew had been told they were getting an old-timer as replacement for their nose gunner. This mission was about the 12th for me.

Off we go into the wild blue yonder. Wild it was! This squadron go lost in the middle of Germany. We were actually lost for possibly up to two hours, flying around in circles. I was watching flak moving toward us when I spotted a German plane about a mole or so away flying our same directions, same altitude, and speed. The plane was called to the pilot’s attention, also the fact that he was evidently tracking us for the anti-aircraft batteries. The flak started moving in on us. A call was made “nose to pilot they have us pinned.” Our young pilot stated he had to stay in formation and follow the lead. About a minute or two of this and the flak started sounding loud and clear. Then in front of me I could see the red bursts, each one getting redder, flak hit the turret, then my voice loud clear,

“For Gawd’s sake, take this SOB up – they’ll have us in 2 more bursts.”

To the young pilot’s credit, he must have figured that a court martial of a pilot was better than a funeral. Up we went, the entire squadron went with us. From then on, we, the squadron, started taking evasive action up and down, change direction, change speed, throw out all chaff (the chaff was thin slivers of foil that helped confuse the German radar). We couldn’t do anything about the German plane. He stayed out of gun range, we in turn dropped our bombs on something – somewhere, then by chance (I guess it was by chance) we were headed for England. A successful mission. The debriefing was classic. Any statement made was pure guess work, I know the intelligence officer didn’t write my remarks down. Most of the crew I had been with were either too young or too scared to drink the bourbon. I volunteered to assist them in this endeavour.

Since I was to have been on a 3 day pass I rushed to our hut, changed clothes then back to squadron headquarters to pick up my pass. The CO, bless his heart, was standing outside headquarters, he looked at me and said,

“Gibbs, aren’t you suppose to be in London?”

“Yes sir, but I volunteered and went on the mission today.”

“Were you involved in that fiasco today?”

“Yes, sir!” The CO hollered to the First Sergeant, “Give Gibbs 2 extra days, he is cracking up.”

Five days in London – ah so.

Arriving in London I immediately headed for a pub that would surely have some of my former crew hanging around. Sure enough Naifeh was there with a dear friend. After giving Jack the grisly details of the mission, he dryly commented,

“Oh, Hell, they will decorate the lead pilot and navigator and send them home.”

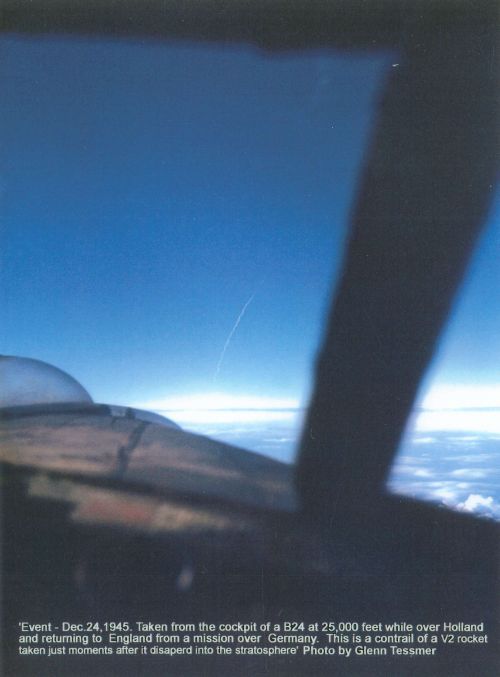

Naifeh and the others had to return to the base, so the Little WAF and I did a tour of London, watched the changing of the Guard, a ride in the tube around most of London. One night when we were returning to her home, we were riding in the top section of one of London’s famed buses when a V-2* rocket cut out. The rocket hit so close that for a moment everyone thought the bus would turn over.

Back to the base for more free lancing. It had to be about this time that I was assigned to the Rosacker crew. Even though all of this crew is still living, none of us are sure just when I joined the crew.

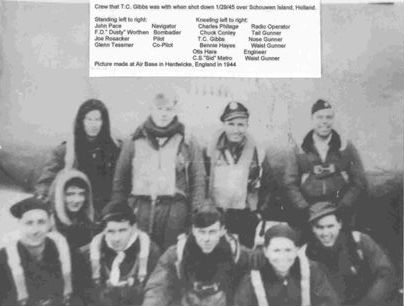

We were indeed a diverse crew

| Joe Rosacker | Pilot | Kansas |

| Glenn Tesmer | Co-pilot | Mass |

| John Pace | Navigator | Texas |

| F.D. "Dusty" Worthen | Bombardier | California |

| Otis Hair | Engineer | Texas |

| Charles Philage | Radio Operator | Pennsylvania |

| Charles Conley | Tailgunner | OregonM |

| Bennie Hayes | Ball gunner | Michigan |

| C.S Metro | Waist Gunner | West Virginia |

| T.C Gibbs | Nose Gunner | Mississippi |

The ball turrets were removed from the B-24’s, as a result Bennie became a waist gunner. The two Texans on our crew were from entirely different areas and backgrounds. Navigator John Pace, was from Dallas; our engineer, Otis Hair, was from Olton, a small town in the panhandle. We were a good crew, congenial, efficient, and dedicated.

We occasionally had the V-2 rockets* come down in the vicinity of our base. One night we had a red alert (red means very dangerous). Several of us were outside our Quonset Hut looking for the V-2. We spotted the thing heading in a general direction of the base. Suddenly it cut out, that meant it was soon coming down. Everyone started scattering, several men jumped into a ditch beside the hut (this was a HUGE mistake since we often on cold or wet nights would use this open ditch as a urinal rather than walk 70 – 100 yards to the latrine). The “ditch jumpers” never did live it down. When we would go to the mess hall, much to their chagrin we would hold our noses, moving with a lot of ceremony to another section of the mess hall. It was all good natured ribbing, but the “ditch jumpers” did have to disinfect themselves and all clothing. The CO and first sergeant wanted to raise hell about using the ditch for a urinal, but they couldn’t keep a straight face when talking about it. War is hell.

Even though I was now assigned to a crew, Naifeh and I still continued our close association. We were fortunate in that our passes well coincided so we could be found in the Piccadilly area on every pass. The little WAF didn’t mention matrimony, neither did it occur to me. A fine war.

On my last trip to London prior to our being shot down, we made big planes to go to Bristol-on-the-sea (with her parents approval), yet those plans were interrupted by events on January 28, 1945. Somehow in the back of my mind I think that long after the war, Croom or Naifeh told me that they told her I was MIA.

The war was going to soon end. This was the word that was spreading fast, we would be heading home by Christmas. Personally I have always thought the allied High Command and our intelligence sections got a bit lax about this time. A wave of bad weather moved into England, no planes could get off the ground. With the big chance in the weather the Germans made their move and what a move it was! With the elite of the German Wehrmacht leading the way, the German Army poured through our lines in a rush to capture Antwerp. At that time Antwerp was the largest military depot in the world. It is pure conjecture, but if the Germans had been successful in capturing Antwerp, intact, the war could have drug on for another year. Fortunately for the allies, Bastogne, a city in Belgium, stood in the Wehrmacht’s path. Thus, the famed Battle of the Bulge.

Back at our base in England and in all the airbases of the 8th Air Force, the British and the other air bases, not one plane could leave the ground. We were “socked-in” tight. Morning after morning we would go to briefing, turn to the planes to wait and wait and wait. After several hours it would be the same – stand down. While this was happening to us, the same thing was happening to the 15th Air Force out of Italy. The Germans had planned well except they had not counted on the Battered Bastards of Bastogne putting up such resistance. In my opinion this was probably the greatest stand by an allied force in WW II. The Air Force could not relieve Bastogne, the Germans were throwing everything they had at them, inflicting severe loses, taking many POWs, but they could not break through in their race to Antwerp.

Finally, after countless days of “standing down” the word was “go” and we did. If a plane had wings it was put in the air. Out of England we poured, B-24’s, the B-17’s with their hand grenades, P51’s, P47’s, then after us came the other Allies in the big Lancasters, the superb Mosquitos (best plane in WW II), and anything else that would get off the ground. It was a sight to behold, planes, planes, and more planes making bomb runs, dropping supplies with the little friends shooting at anything that moved. The day was so clear that I spotted a German Tiger tank cutting through the snow. As we headed back to England, the 15th out of Italy started arriving. After that one day, the most diehard Nazi must have realized that all was “Kaput”. Allied High Command must have realized the war wasn’t over, therefore the bombing of Germany’s Industrial Might intensified. It seems to me that we stayed in the air.

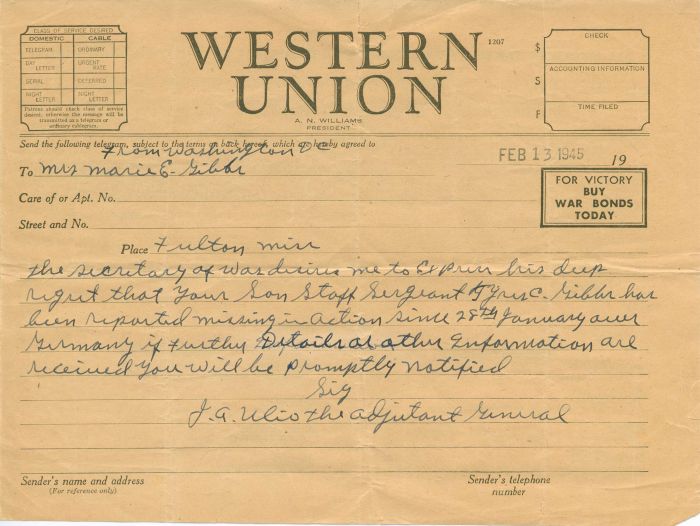

January 28, 1945 was to be our red-letter day. The target was Dortmond in the Ruhr Valley (the Ruhr was know as Flak Alley). The Ruhr was the heart of Germany’s Industrial Might. Our missions into the Ruhr had one simple objective – destroy the Ruhr at all costs.

Our flight started as usual, assembled over England, then over the Zuider Zee to the IP (initial point) then make the bomb run through heavy flak, drop, and head for home. A good plan except for the fact we lost an engine, Joe and Glenn couldn’t feather the windmilling prop, the net result being we couldn’t maintain speed or altitude, therefore, we had to drop out of formation and call for little friend protection (a lone bomber was what the Germans loved).

The squadron was notified of our predicament. Since we were flying squadron deputy, our spot in the formation was immediately occupied by the next plane. We had to turn back to head for the coast and Allied territory. The plane that moved into our position was hit in the bomb bay and exploded shortly after moving into our slot. I would later see 3 of the men on this plane. They were POWs. I asked how did they manage to live through the explosion, their answer was that they were blown out of the plane. One of the men said when he came to, he was floating to earth, his parachute open. Many strange stories similar to this came out of the war.

On our desperate run for the coast and friendly forces, we dropped our bombs on something – somewhere – threw out all guns, and all things that would lighten the load. We continued to lose altitude. Then a second engine went out, the situation had gone from serious to damn serious. We hit the North Sea coast line, everyone knew there was no way we could cross the North Sea, therefore down the coast, hopefully, to Allied lines. By this time we were moving sideways, losing altitude at an alarming rate, and everyone in the world shooting at us. Then it went from bad to worse, a third engine was either hit or just got tired. There AIN’T no way a B-24 can fly on one engine. Joe hit the jumpbutton, by this time Dusty, and possibly Johnny, had come back to the waist section. I had been there for sometime. When Joe hit the button, I looked down at Schouwen Island, it looked like a postage stamp, I looked at Dusty and said,

“Is he kidding?” I remember that question as clear as if it were yesterday. Dusty had one comment, “No Gibbs, get the hell out of here.”

With that I dropped through the waist escape hatch, calmly counting to ten prior to pulling the parachute handle (we had never practiced a parachute jump, but had been told to count to ten prior to pulling the parachute handle). I did, in this fashion, 1-2-6-10! The chute opened (I said a little thank you prayer to the packer). While floating earthward, I saw chutes in every direction, yet could count only eight other than myself. Who didn’t get out? Our B-24 seemed to be heading for the ground when it suddenly turned upward, so help me the plane was heading straight for me. Suddenly, when I thought sure the plane would strike me, it turned over heading straight into an open field where it crashed and burned.

Riding a parachute down is a most unusual trip. To me there was no sensation of falling until the ground starts rushing up to meet you. When this started happening I saw the area where I was heading had large poles sticking up everywhere. The poles were akin to light or telephone poles, placed where they were, to prevent allied gilders and/or planes from landing. Somehow I was able to swing and maneuver myself between the poles. Believe me, when you hit the ground it would be similar to jumping from the roof of a house.

Once on the ground the chute was hastily rolled up, shoved into a small thicket of bushes and scrub trees. I jumped into a small ditch that had some scrub trees on the banks. It was COLD, and as soon as I stepped into the ditch, the ice broke,and one of my flight boots was now filled with water. In my mind, a foot would be lost of frost bite. Yet, at the time this was the least of my worries. The first thing to do was look at my escape map to try to determine my present location. About the only thing that made sense was we had landed on an Island, off the coast of Holland, near the North Sea. The thought kept running through my mind – what in the world is this old boy from Itawamba County, Mississippi doing in this predicament. I wasn’t mad at anyone, yet the entire German Army was out to kill me. My foot was freezing, I was freezing, my entire world had been turned upside down.

Peeping out from the bushes, a man was spotted waving his arms at me. For better or worse I ran to where he was standing. There was a language barrier between us, yet there was something about the man that said he was trying to help me. He quickly hustled me inside his house. Bennie was sitting in front of a big fire, he had hit the side of the barn and was in a hazed condition. Within a half minute a lady rushed into the room with a glass of spirits. I gulped the stuff down. It must have been 200 proof, for a warm glow was immediate. During all this, I could hear dogs barking. Suddenly the door burst open and in came the Germans. One, a soldier of maybe 17 years old, shoved a burp gun in my face (it looked like an 88m cannon), screaming at Bennie and me. The lady ran out of the room. The man signaled for us to raise our hands. We were now POWs.

In 1972, Joe and his wife, Dusty and his wife, Otis, Dot, and I visited Schouwen Island. So many changes had been made we were unable to locate any place. After we returned home we received a letter from a man, Mr. Boot, who was the Burgermeister of that area when we were shot down. In his letter he told about his mother giving some US Airman some spirits. She was arrested by the Germans, tried and released due to his influence and the fact the German court asked her if those men had been Germans would you have done this? She replied “Yes”.

* = The writer probably means the V-1 bomb instead of the V-2 rocket.Definitielijst

- cannon

- Also known as gun. Often used to indicate different types of artillery.

- flak

- Flieger-/Flugabwehrkanone. German anti-aircraft guns.

- MIA

- Missing in action, Missing.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- radar

- English abbreviation meaning: Radio Detection And Ranging. System to detect the presence, distance, speed and direction of an object, such as ships and airplanes, using electromagnetic waves.

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- rocket

- A projectile propelled by a rearward facing series of explosions.

- Squadron

- A military unit in the Belgian navy usually six to eight small ships operating together under one command. The smallest military unit in the Dutch air force of about 350 men. In most countries is the designation of a military unit thesize of a company. It is either an independent unit, such as a battery, or part of a bigger Calvary unit. In the air force it is the designation of a unit of aircrafts.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Images

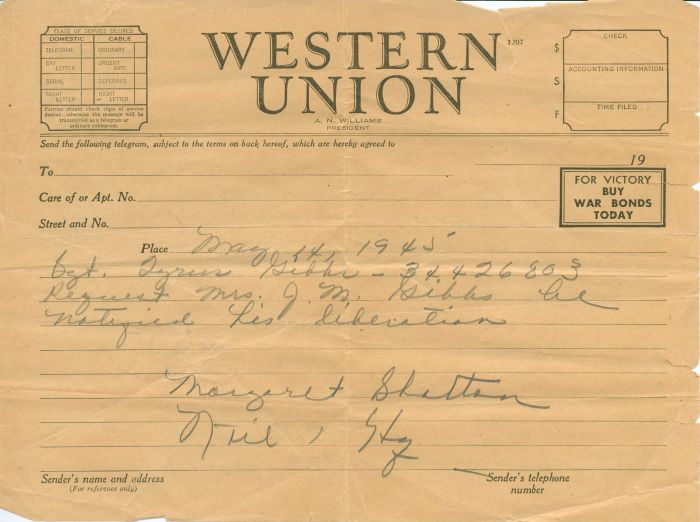

Prisoner of war

Men in combat may think about an injury, some may adopt or become something of a fatalist, yet I never heard one that spoke of becoming a POW. It just didn’t cross your mind. Yet here we were, POWs and would remain such until the war with Germany would end. There were later incidents that raised considerable doubt as to whether we would survive until war’s end.

After our surrender to the troops and dogs that surrounded the Dutchman’s house, we were stripped of our worldy goods (I always carried several packets of cigarettes, Lucky Strikes, 4 or 5 of the British 5 pound notes in my gear), these items, my beautiful watch, pistol, knife, and few lesser items were in the hands of my captors (the cigarettes and five pound notes were trading items). We were marches through the little town to the German’s headquarters. Upon our arrival at HQ we were separated. For some reason I was left out in the long hall with a young (16/17 years old) guard. In no time it was most evident the German officers were enjoying my cigarettes. The captors had left me with about half a pack. I fumbled one out, no match! The young guard noticed my situation, when no one was in the hall he handed me a small box of matches. That was one fine smoke. As soon as I lit up I started to hand him the matches, he was shaking his head in a negative manner. There was a non-com walking down the hall, after the non-com passed, I slipped the young guard his matches and a couple of my precious cigarettes.

In an hour or so I was called into a room with two German officers. The questions were fired at me from both of them,

“What BG? How many crew members? Our target?”.

After each chance to answer, it was the same.

“My name is Staff Sergeant Tyrus C. Gibbs, 34426803, US Air Force”.

I must have repeated that eight to ten times.

One of the officers screamed,

“Damn it Sergeant, we know your name, rank and serial number.”

(Under the Geneva convention that was all I was required to give them. Germany was a signatory to this convention). On the desk in front of the officers were several items of mine, watch, fountain pen, mints, and a Vicks inhaler (the writing was gone from the inhaler), one of the officers pointed to the inhaler, “Vas es Los?” (What is this?)

Again, my response was name, rank, and serial number. The officer picked up an intercom, snapping out sharp orders. In about thirty seconds an enlisted man entered the room with a pair of tongs, he gingerly lifted up the inhaler, held the “secret weapon” at arms length, departing the room immediately. My watch, fountain pen, a few mints, and chewing hum were returned to me.

The German officer’s command of the English language was impeccable, one commented,

“We know you are from the South.”

How did he guess. Prior to dismissing me one of the officers asked,

“Are you scared?”

My answer, “No, sir”.

Surely the good Lord won’t hold that big lie against me.

From the interrogation to a holding cell where most of the crew was being held. It was a welcome sight to see the crew, also to learn that ten parachutes were counted. That meant that everyone made the jump. By this time my foot that had gone into the ice water felt as if it were frozen. One of the fellows, I can’t remember which one, helped me get my boot off then vigorously rubbed my foot to help restore the circulation. I still believe this saved my foot from freezing. Prior to putting my foot back in the boot, I dried the boot as good as possible, wrung out the sock, used an undershirt for lining, making life much more bearable.

After short rations to eat, we were loaded on a small boat for a trip to the mainland. By the time we were loaded on the boat it was dark and cold (bear in mind we were almost in the North Sea in the dead of winter.) We landed in Rotterdam, staying there for a short time, then put in the back of open trucks for the first leg of our journey to Germany and the POW camps. Riding in the back of the truck through Rotterdam, I well remember these brave Dutch people, men, woman, and children, at every opportunity giving us the V for Victory sign. Men scratching their faces with their fingers forming a V, when the guards backs were turned, women throwing V kisses, even the youngsters making the V signs. It was most heartening for some GIs who were having a bad day. Down into Germany by various means of transportation.

Somewhere along the journey we were split up into two groups; pilot, co-pilot, navigator, bombardier, radio operator, and myself made up one group. I am not sure if the other four were able to stay together. Prior to splitting our crew, there was an incident that caused me to think “This is it”. In some town, not sure where, the ten of us were confined upstairs in a building. We were placed behind barbed wire with a German guard manning a machine gun pointed straight at us. There was a big pile of hay on our side of the wire. The hay made a super warm bed, in minutes I was sound asleep. On awakening the only crew member left in our area, was Bennie. I asked,

“Where is everyone?”

Bennie, in a trembling voice, replied,

“Gibbs, they have been carrying everyone out, one at a time.”

No sooner had he said this, than a machine gun opened fire from some area downstairs. Bennie didn’t help lifting my spirits when he said the machine gun opened fire every few minutes. This was it – what we had heard about Germans killing prisoners was true! Suddenly all my thoughts were about home, Mother, Dad, Jimmy, Bonnie, Ruth and Paul. A little prayer kept running through my mind. “Dear God, please let me die like a man in a way that would bring no dishonor on my family or my country.”I must have repeated that prayer a dozen times before the guard summoned me to follow him.

Again, I was sent to an office for more interrogation.

“Where is your home? We need to notify the Red Cross that you are alive and well”.

This and similar questions were asked with name, rank, and serial number as my response. I think it was after this episode that the crew was separated.