Airraid on Kleykamp

Introduction

The population registration administration and personal identity documents were an important checking tool for the German occupying forces. Slowly but surely a resistance movement developed itself against this system. The forging of these documents became a sophisticated issue. Another possibility was the elimination of the administration registers. One of the most well-known examples thereof is the attack on the Kleykamp in The Hague. The remarkable fact of this attack is that it was not carried out by the resistance movement itself, but by aircraft of the Royal Air Force.

Identity Cards

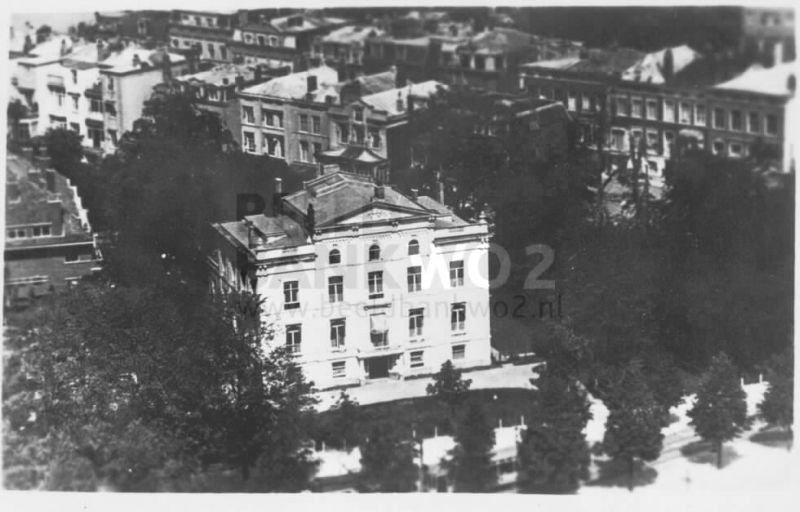

The Kleykamp mansion was a large white house at the Scheveningseweg in The Hague. In 1916 it became an art exposition and cultural centre. In that capacity it would eventually even be called the Royal Art Centre Kleykamp. Up to 1941 there were regular art exhibitions and lectures. In that year the German occupying forces introduced the obligatory identity card. Also a centralized registry had to be set up where duplicates of all issued identity cards could be stored. This shadow registry was established in the Kleykamp Villa in August 1941. The Sicherheitspolizei [German state security police] had free access to this register and therefore to an exceptional checking method of the personal identity cards of suspect persons.

In order to sabotage the efficiency of this checking method, documents were forged by the various resistance units. There grew an increasing need for forged passes. Jews received a “J” in there personal identity card, which enhanced their identification. Also resistance members that were registered with the criminal investigation department of the Sicherheitspolizei required a forged identity card. In July 1942 the Persoonsbewijzencentrale (PCB) [The Registration Office of Personal Identity Cards] was erected by amongst others Gerrit Jan van der Veen. This resistance organization printed until the end of the war in 1945, approximately 80.000 forged identity cards. Also the Falsificatie Centrale (FC) [Forging Centre], in Nijmegen established in 1942, played an important part in the document forging activities. This FC would later on be merged with the Landelijke Organisatie voor Hulp aan Onderduikers (LO) [National Organisation for Assistance to Persons in Hiding].

Not only the forging of the personal identity cards was a way and means to sabotage the control methods. Another option was the elimination of the population registries. Archives and collections of documents were destroyed or requisitioned by the various resistance groups. These were however rather smallish activities with rather little results.

Request to the RAF

The shadow archives in the Kleykamp Villa were a powerful weapon for the German occupational forces and its destruction would be an important advantage for the resistance movement. But within the resistance movement there was not enough power to commit a large assault on the Kleykamp mansion. Apart from that, the house was well guarded and surrounded by a moat.

In July 1943 the Dutch resistance fighter Pierre Louis d’Aulnis de Bourouill was dropped out of an airplane over The Netherlands as a secret agent. He became the communications officer between the resistance and the Dutch-Government-in-Exile in London. On December the 16th 1943 he passed the request on to the (Dutch) Intelligence Office in London to have the Centrale Bevolkingsregister [Population registry] bombed by the Royal Air Force.

The contents of the telegram in Dutch can be translated as follows:

“Permanent forgery of the personal identity cards impossible because a governmental inspection department, manned by German sympathizers [NSB] , of the population registry holds copies of all real data. It has been established that these copies are exclusively and completely saved in a housing in The Hague, destruction of same not possible by us. In case RAF destroys these archives, we will be able to forge the municipal registry which will make many persons legal.”

After elaborate discussions between the Dutch Government and the RAF it was decided to carry out an air attack. 613 Squadron (unit of the 2nd Tactical Air Force) was appointed to carry out the orders. The mission was prepared under top secret circumstances. In order to prepare the flight crews as detailed as possible of this “special operation” mock ups were build of the Kleykamp mansion and its surroundings of The Hague. During the briefing on the morning of the attack also a number of higher ranking air force officers participated. They emphasized that “the target was of a great political importance and the total destruction of it to be of essential value”.

The Attack

Tuesday April 11th was the day of the attack, which had deliberately been planned to take place on a working day. The chances were greater that the archive cupboards would be opened and that personal identity cards would be placed on the desks, which would enhance the chances for destruction of this shadow archive. Also the time frame of the attack, a little before 15:00 was carefully planned, in order to avoid the fact that there would be too many people in the streets. The attacking force consisted of only six fighter bombers and Squadron Leader Robert Bateson, commander of 613 Squadron was in charge. One of the Mosquitoes was piloted by 21 year old Robert Cohen, a student of Delft University. Cohen was of Jewish descent and succeeded together with a co-student to cross the North Sea between 19 and 22 June 1941 in a canoe and to reach England. There he volunteered with the Royal Air Force. The remainder of the aircraft was crewed by British of the Commonwealth.

De Havilland Mosquito LR355

Wing Commander Robert Bateson.

Flying Officer B. Standish

De Havilland Mosquito LR376

Flight Lieutenant Peter Cobley

Flying Officer G. Wlliams

De Havilland Mosquito NS844

Squadron Leader C. Newman

Flight Lieutenant F. Trevers

De Havilland Mosquito NP927

Flight Lieutenant R. Smith

Flying Officer J. Hepworth

De Havilland Mosquito NI408

Flying Officer Robert Cohen

Flight sergeant Peter Deaves

De Havilland Mosquito LR366

Flight Lieutenant V. Hester

Flying Officer R. Birkett

The six aircraft took off at 13:05 (GMT) from RAF station Swanton Morley in Norfolk. A short report of the attack, made by Wing Commander Bateson was edited in the “Vliegende Hollander” [Flying Dutchman] (a small newspaper which was dropped by the allied air forces) of Thursday May 4th , 1944, and which can be translated as follows:

“We flew very low. The inundation of certain parts of the country, looking like marshes, did not help to make it easier to find our way. At first we thought to be over the wrong coastal area, but when we finally managed to find our way all went smooth. On the mock up we had paid especially attention to a number of chimneys, but when we arrived at the spot we saw so many chimneys that we didn’t trust too much on those marks. I ascended to approximately 700 meters, took a good look around and noticed at a distance of approximately six kilometers, the tower of the Peace Palace, which was situated really close to the target. I descended again and started the nose dive towards the target.

The building counted five stories and was estimated to be 25 meters high. We bombed from an altitude of approximately 18 meters, so lower than the roof. A sentry was posted outside, but he threw his rifle away and ran. I myself could not see what happened but my number 2 told me later, that he had been able to follow my bombs exactly, that one hit the middle of the front door and that the two others entered two large windows.

All bombs landed on the target and the incendiaries functioned as intended. When number 5 and 6 had had their turn nothing very much remained of the whole building.”

Aftermath

The Kleykamp Villa had been turned into a sea of flames. Some houses around the mansion were also destroyed as a result of the explosions. But in spite of the fact that the building was completely in ruins, it appeared that the attack had been less effective than hoped for. Only less than half of the shadow archives had been destroyed. Many personal identity cards and other documents had been safe in the fire resistant archive cupboards against the destruction by the falling debris and the fire. The Germans cleared those documents from the ruins in the weeks that followed and stored them somewhere else.

At the attack 59 people lost their lives. Most of them were occupied in the “Centrale Bevolkingsregister” [Central Registry]. It had been assumed that these employees were collaborators with the German occupying forces but this was not correct. There appeared only to have been a few collaborators amongst the staff, the others were innocent people. Afterwards many asked themselves often why this attack had been planned on a working day. The effect proved to be not much greater, but had resulted in significant number of civil victims. Also the fact that the attack took place only in April 1944 and not much earlier during the occupation generated the discussion about the advantage of the attack. The deportations of the Jews for example had by that time already been finalized.

De crews of 613 Squadron completed the mission without losses.

“We escaped, as a matter of speech, without a shot being fired at us. The Germans had no idea of what was happening. An escort group of Spitfires was waiting for us to guide us home safely.” Said Bateson. The commander was awarded the Distinguished Flying Medal (DFM) for demonstrated courage and determination during a secret operation. Resistance member Pierre Louis d’Aulnis de Bourouill was awarded the Militaire Willems Orde [ Highest Military Medal] .

Definitielijst

- Commonwealth

- Intergovernmental organisation of independent states in the former British Empire. A bomber crew could include an English pilot, a Welsh navigator, air gunners from Australia or New Zealand. There were also non-commonwealth Poles and Czechs in Bomber Command.

- inundation

- “Latin: No bottom”. The deliberate flooding of land with the aim of stopping or hindering the advance of the enemy into a certain area.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- NSB

- National Socialist Movement. Dutch political party sympathising with the Nazis.

- RAF

- Royal Air Force. British air force

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Squadron

- A military unit in the Belgian navy usually six to eight small ships operating together under one command. The smallest military unit in the Dutch air force of about 350 men. In most countries is the designation of a military unit thesize of a company. It is either an independent unit, such as a battery, or part of a bigger Calvary unit. In the air force it is the designation of a unit of aircrafts.

Images

Kleykamp Villa, before the attack. Source: Beeldbank WO2.

Kleykamp Villa, before the attack. Source: Beeldbank WO2. The building is being struck during the attack. Source: Beeldbank WO2.

The building is being struck during the attack. Source: Beeldbank WO2. The smoldering ruins of the Centrale Bevolkingsregister (the population registry). Source: Beelbank WO2.

The smoldering ruins of the Centrale Bevolkingsregister (the population registry). Source: Beelbank WO2. The destruction after the attack. Source: Beelbank WO2.

The destruction after the attack. Source: Beelbank WO2.Information

- Article by:

- Pieter Schlebaum

- Translated by:

- Fred Bolle

- Published on:

- 29-12-2011

- Last edit on:

- 30-09-2024

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Related books

Sources

- HEIJBROEK, F., Kleykamp, Waanders B.V., Zwolle, 2008.

- JONG, L. DE, Het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden in de Tweede Wereldoorlog 7, Staatsuitgeverij, Den Haag, 1969.

- ROEGHOLT, R. e.a., Het verzet 1940-1945, Unieboek b.v., Weesp, 1985.

- SCHULTEN, C., En verpletterd wordt het juk, Sdu Uitgeverij Koninginnegracht, Den Haag, 1995.

De Vliegende Hollander No.30 (4 mei 1944)

Andere Tijden 23 oktober 2008