Resistance in Belgium in World War Two

In the thirties of the 20th century Central Europa came increasingly under influence of Germany. The Anschluss was realized and also the Sudetenland was annexed. The other powers in Europe let Germany get away with this. This however didn’t happen when Germany invaded Poland on September 1st 1939. Two days later France and Great Britain declared war on Germany. World War Two had started. Belgium also was involved: on May 10th 1940 Belgium’s neutrality was violated. The Belgian army wasn’t a match against the German onslaught and received one hammer blow after the other. After an 18 day campaign the Belgian king Leopold decided to lay down arms.

The first months of occupation

When the Germans invaded Belgium thousands of Belgians were caught by deadly fear. The dark and scaring memories of the German atrocities in the Great War came to life again. Interestingly enough this fear quickly subsided when the people were confronted with a very disciplined and even affable German army. Except for the killings in Vinkt during the actual fighting there was no trace of terror or outrages.

Paul Struye, publisher of the clandestine La Libre Belgique wrote in his diary that was later published: "During the first months there really was no enmity to be detected between the population and the army. It was a pleasant surprise for the Belgians to see the German soldiers, correct in their attitude and other behaviour. They had nothing in common with the imperial troops of 1914-1918. Belgium was occupied by an army in which order and discipline reigned without outrages. "

Besides that it seemed the war was won by the Germans. Almost everyone, including king and government, thought that Great Britain would go down quickly and would be obliged to accept a compromise peace. Who would risk one’s life for a seemingly lost cause? After the capitulation there followed no deluge of anti- German actions. When these occurred on a small scale the perpetrators couldn’t count on sympathy or support from the population who feared German reprisals. Resistance in the first few months really was almost not existent. The occupying regime grew harder and slowly a pro-British attitude submerged. The succession of decrees, like among others the suspension of municipal and provincial councils and the implementation of a curfew led to resentment among the population. The problems with the supply of food turned public opinion wholly against the Germans.

On top of that Germany suffered her first major setback in World War Two: She lost the Battle of Britain. Germany turned out not to be invincible. All this brought a change in the mood of the population and offered the resistance a fertile ground. The resistance spread slowly and started to become a menace for the occupying military administration.

Intelligence services

Intelligence services comprised all networks that collected information that could be useful for the allied war effort and managed to pass this information through an organised network to these allies. This definition is important in order to discriminate between other organisations of resistance that also had an intelligence branch but only used this for their own benefit.

The most important intelligence service in Belgium was active under the name Clarence and was commanded by Walthère Dewé. During the Great War he commanded the network La Dame Blanche in service of the British Intelligence Service. Because of the magnificent results that he had got Dewé was called upon again in 1939. He didn’t hesitate for a second. Next to Clarence two other prominent intelligence services came into being: Zero under command of Frans Kerkhofs en Luc (from 1942 on Marc), the largest in number of agents under command of Georges Leclercq.

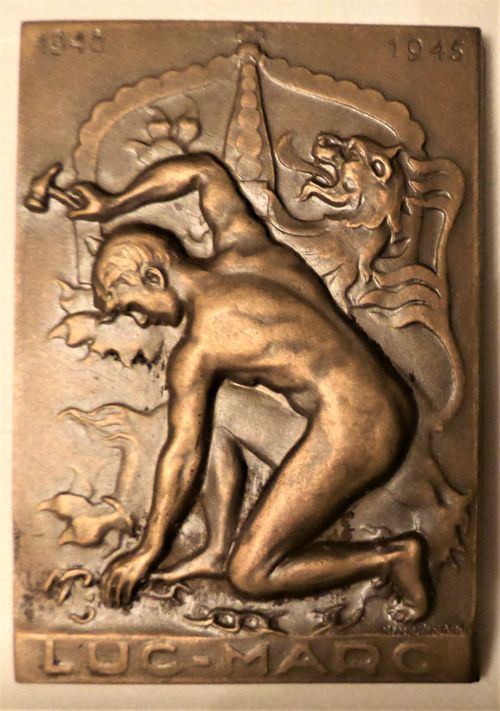

Commemorative copper plaque received by members of intelligence agency Luc after the war. Source: Christine Vinck

Onward from 1941 a permanent connection was established between Belgium and London. The intelligence services informed the allied supreme command about almost everything which went on in Belgium: The German defensive system on the Belgian and Northern French shore, everything concerning airports, AAA and coastal batteries, stockpiles, traffic, communication and German orders with Belgian companies. The internal organisation of such an intelligence network can best be compared to a large pyramid of which the basis is formed by thousands of observers that looked at their immediate surroundings. Divided into sectors they were coordinated by the top of the chain of command. In order to guarantee as much safety as possible the network was divided into many smaller cells that comprised just a few agents and that had no contact with other cells, unless through one contact person. In this way it was difficult for the Germans to eliminate the whole network. The intelligence services led a life completely separated from the other resistance organisations.

The collected intelligence was mostly put on micro film and transported to London. Sometimes carrier- pigeons were used, but this method proved to be unreliable. Another option was to bring the intelligence to unoccupied France where there was less control and contacts with the British could be made. Spain and Portugal also became important gateways to London. Finally there were wireless operators that sent coded messages to the other side of the North Sea. They were the most vulnerable because the Germans made great progress in localizing the transmitters.

All these intelligence services quickly received a reputation. In a report from the Abwehr, the German counter espionage service, literally it was written that from all intelligence services the Belgian were the most dangerous.

Lines of escape

The most important goal of the lines of escape was to transport to Great Britain downed allied pilots, Belgian military personnel that would join the armed forces in Great Britain and Belgian resistance fighters that had to disappear because they were "burned" (known to the Germans). Besides that Jews, Dutch resistance personnel and POW’s that had escaped from Germany were transported. The Komeet line, founded by Andrée de Jongh was the most famous but by far not the only line of escape. The Komeet was the only line that had a fully own infrastructure from Belgium to Spain. The work of running such a line needed a vast number of operatives (around 2,000) that had to take care of shelter, food, clothing, false papers and guides. The pilots, called "colli" ( packages), "klanten" (customers) or "enfants"(children) in the escape business, departed by train from Brussels to Quiévrain, where the border was crossed on foot. From there the trip continued to Paris, now with a French identity card and on to Bayonne from which they travelled to Anglet. Then the journey was started over the Pyrenees where the pilot was brought to the British consul. In total Komeet which was known as a safe escape line transported over 700 allied military personnel.

For the agents themselves the work was fraught with danger. Because of the length of the line and the nature of the work escape lines were very sensitive to infiltration or German counterespionage. No less than 800 from the operatives of Komeet were arrested from which at least 155 perished in camps in Germany or were executed in occupied territories.

Sabotage and armed resistance

These resistance groups came about spontaneously even more so than other resistance groups. We can distinguish three large groups: "Groep G" as an example from an organisation which was stimulated by the British sabotage service; "De Partizanen" as the armed branch from the Kommunistische Partij van België (KPB), the communist party and the "Geheime Leger" or secret army as exponent from resistance led by former Belgian military personnel.

Groep G (Groupe Général de Sabotage) was actively supported by the SOE, the Special Operations Executive, the British sabotage service. One SOE agent, André Wendelen, was dropped in January 1942 into Belgium with orders to establish a new sabotage group or make contact with an existing group. He laid contact with Jean Burgers, Robert Leclercq, Henri Neuman and Richard Altenhof, the four founders of Group G. From the spring of 1943 the structure of this organisation was established and she was capable of starting coordinated actions to inflict as much damage as possible to the occupying forces, without destroying needlessly or to provoke reprisals. The sabotaging was very simple: cutting of brake circuits, unscrewing of rail bolts, adding sugar to petrol tanks etc. Also railway tunnels, pillars of bridges, sluices and the like were destroyed. The most spectacular action from Group G took place in January 1944 and is known as the "grande coupure" or "great interruption". The electrical high tension network over almost the entire Belgian area was knocked out of work in one go through a series of coordinated actions. Despite the relative limited number of active members (approximately 4,000) Group G had the highest number of sabotage actions on its account.

De Partizanen were the armed branch of the KPB, the Belgian communist party, the only political party as such that chose for resistance. She was affiliated closely to the Onafhankelijkheidsfront or Independence Front, a broad Belgian-patriotic front that came into existence by a communist impulse. First the actions of the Partizanen remained limited to relatively simple acts of sabotage. From the summer of 1942 onwards the actions got tougher and they started to target quite literally collaborators, informers and even German soldiers. By these assaults the Partizanen wanted to let the occupier feel that he wasn’t the sole master in Belgium. They committed hundreds of assaults and acts of sabotage, most of which in 1943 and 1944. No exact figures are known about the number of Partizanen. After the war more than 11,000 were acknowledged, but this number is probably a lot higher than reality.

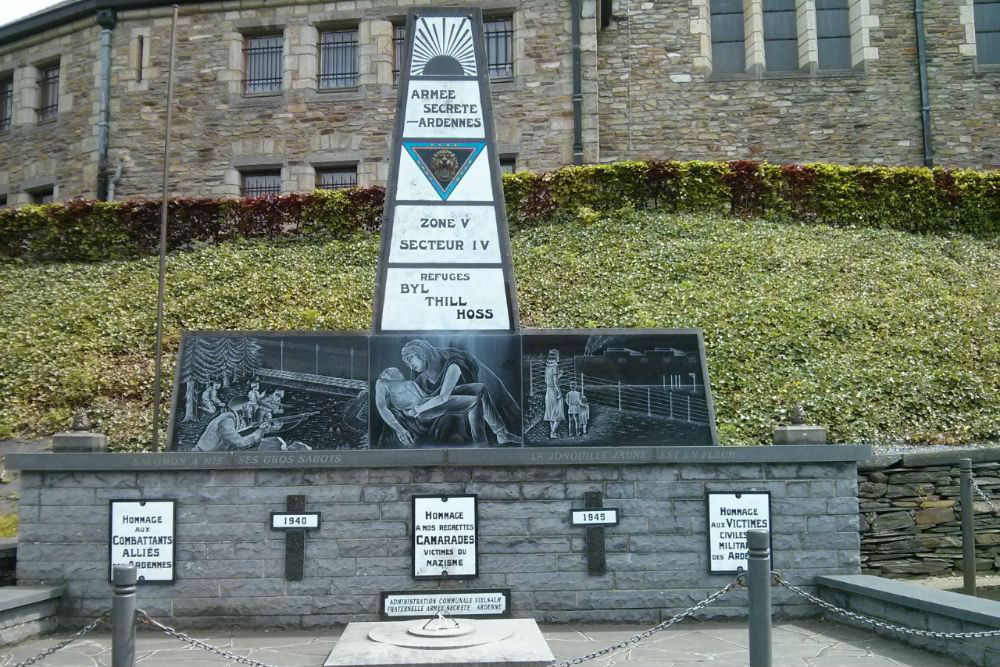

Het Geheime Leger or the Secret Army was a merger of various small groups of military personnel that didn’t want to accept the defeat of May 1940. This merger only occurred after lots of problems and internal conflicts in which even the Belgian exiled government played an active part. Since 1943 the relations between London and the secret troops had been regularised. It was decided that the secret troops would only become active when the allied invasion would start. Since 1943 sabotage actions were perpetrated. Especially since June 1944 the Secret Army got into action. She started with interfering the railroad traffic and bridges and sabotaging the German lines of communication. Among others 95 railway bridges,15 sluices and 17 tunnels were destroyed. Due to a lack of explosives the Secret Army didn’t succeed in blocking the German transports and lines of communication totally. In the same time she had an anti-destruction assignment which consisted of trying to keep the Germans from destroying strategic points and major crossroads when they retreated. In this context it is worthwhile mentioning the capture of the intact harbour of Antwerp which greatly helped resolve the logistical problems for the allies. From the end of August 1944 the government ordered the Secret Army to attack the enemy through guerrilla actions. Because of geographical reasons these were only conducted on a limited scale in the Ardennes. After the liberation 54,311 members of the Secret Army were acknowledged as armed resistance fighters, from whom 4,000 were killed during the war.

Definitielijst

- Abwehr

- Term used for the German military intelligence unit during the WW1 and WW2. From 1935 onwards under command of Admiral Wilhelm Canaris. The organisation often came into conflict with other secret services such as the SD and the Gestapo. During World War 2 under Canaris frequently a source for conspiracies against the Nazi regime until in 1943 a major conspiracy by a number of prominent members of the Abwehr was discovered and the Abwehr was placed under command of Himmler. After the assassination attempt on Hitler in 1944, Canaris was discharged and the Abwehr was dissolved. The conspirators and Canaris were prosecuted and in 1945 they were executed atc oncentration camp Flossenburg.

- capitulation

- Agreement between fighting parties concerning the surrender of a country or an army.

- infiltration

- Quiet incursion into enemy lines prior to an attack.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- neutrality

- Impartiality, absence of decided views, the state of not supporting or helping either side in a conflict.

- POW

- Prisoner of War.

- Resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- SOE

- Special Operation Executive. British organisation during World War 2 conducting secret operations and espionage.

Information

- Article by:

- Gerd Van der Auwera

- Article by:

- Peter ter Haar

- Feedback?

- Send it!

The War Illustrated

Related sights

Related books

Sources

- HERMAN VAN DE VIJVER & RUDI VAN DOORSLAER, België in de Tweede Wereldoorlog 6, De Nederlandsche Boekhandel, Kapellen, 1988.

- HERWIG JACQUEMYNS, België in de Tweede Wereldoorlog 2, De Nederlandsche Boekhandel, Kapellen, 1982.

- MEYERS, W. & SELLESLAGH, F., De vijand te lijf, Helios, Antwerpen/Amsterdam, 1984.

- PAUL LOUYET, België in de Tweede Wereldoorlog 4, De Nederlandsche Boekhandel, Kapellen, 1984.

- SCHWEGMAN, M., Het stille verzet, Socialistische Uitgeverij Amsterdam, Amsterdam, 1980.

- VERHOEYEN, E., België bezet, BRTN, Brussel, 1993.