Introduction

The story of Fred Seiker and his paintings can be found at: Fred Seiker, Lest We Forget.

Comments of the Author

I could have made this story longer by including, for instance, tales of childhood in Rotterdam, hobbies, varied and interesting holidays, his daughter Melanie and grandchildren Alexis and Micha, other family members, good friends we have both made.

They would have made a more complete picture and have all been an important part of Fred's life, which he considers has been a very fulfilling one.

But I wanted to show his ability, tenacity and courage, sometimes through indescribably terrible times, and I know I have succeeded.

I love him and am very very proud of him.

Liz Seiker

Rotterdam

Mathias Frederik Cornelius (Fred) was born in 1915 to Gertrude and Frederik Seiker in Rotterdam. He was the eldest of four children, two girls and two boys.

Theirs was an ordinary hardworking family but despite poverty and hardship Fred experienced a very happy family life with parents who worked hard to provide for their children. During the Recession Fred's father travelled the country to find employment and his mother went out getting paid housework, sometimes going without meals so that her children could eat.

Entertainment was not available but the children made their own homemade games. There were no holidays but a one-day visit to the seaside in the summer. The rest of the year there were occasional special food treats.

Fred's father was an engineer whose career began on the large powerful Rhine tugboats plying between Rotterdam and Basle. He later developed an interest in" industrial refrigeration and became known as one of the leading experts in Holland in that field.

After Fred had attended Primary School he went at age thirteen to a Technical College where he took a three-year course in engineering. This was followed by a two-year practical apprenticeship, part of which was served with Wilton shipyard in Rotterdam, part working with his father when Fred became familiar with industrial refrigeration. At the same time he attended evening school and took an advanced course in general engineering.

He succeeded in obtaining a place at the Rotterdam Marine Engineering College though because of the family finances his father had a hard time seeing his son through college. After obtaining his first sea-going diploma he was recruited by the leading shipping company at that time, Rotterdam Lloyd, who only took the best recruits, and began his career as a marine engineer. Fred remembered always the great pride of his father when he saw his son in uniform for the first time.

During his career with Rotterdam Lloyd Fred travelled the world. He took to the life and work of a seaman, felt totally suited to it and was always happiest when at sea. He progressed to the rank of Third Engineer.

Images

Start of the war

In 1938 Fred did not know it but he sailed on his last trip from Holland and would not return to his native land for over seven years. In May 1940, as his vessel was en route to his home port of Rotterdam, the captain received a signal to make for Weymouth Bay, UK, as the Nazis had attacked Holland. Because the small Dutch army had dared to resist their invasion the Nazis had obliterated the centre of Rotterdam by air bombardment.

Eventually Fred found himself in the port of Tilbury, Essex, awaiting further orders and during his ship's extensive stay in port he met and fell in love with an English girl, Edna.

His ship was instructed to make for Canada and visited some of the larger ports on the US Eastern Seaboard where they took on board several thousand tons of scrap iron. They passed through the Panama Canal to Kobe, Japan, where ironically the entire cargo of scrap iron went into a factory specializing in the manufacture of armour plating for the Japanese navy.

On arrival at the port of Tandjong Priok (port of Jakarta) in the then Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) Fred volunteered to serve on ships supplying Britain with food and war materials. He made several North Atlantic convoy crossings from the US Eastern Seaboard to Liverpool but although one convoy came under sustained U-boat attack his ship escaped serious damage. During a brief shore leave whilst in Liverpool he became engaged to Edna.

Fred's ship was eventually taken out of convoy duty and ordered to make for Java in the Dutch East Indies where he was transferred to a German vessel which had been confiscated by the Dutch Royal Navy.

From Java he went to Singapore where they took on board a cargo destined for Liverpool. The ship left Singapore to make for a convoy rendezvous in the Gulf of Dakar, via Capetown. A few days out of Dakar the ship was hit midships by a torpedo killing the entire engine room crew on duty at that time, including a colleague who was Fred's closest friend. The ship was abandoned in calm and orderly fashion and all survivors were picked up by a British corvette.

Definitielijst

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

- U-boat

- The German name for a submarine. German U-Boats (Submarines) played a very important role during the course of warfare until May 1943. Many cargo and passenger ships were torpedoed and sunk by these assassins of the sea.

Becoming a POW

Fred eventually arrived back in Java via Durban and whilst he was waiting to be placed on another ship the Japanese invaded. He volunteered for service into the Dutch army there but within a short period he became a prisoner of war of the Japanese, spending a short while in a POW camp in Bandung before being transported via a 'hell ship' to Changi jail in Singapore. On the voyage from Java to Singapore he soon learnt what it meant to be a POW of the Japanese. The journey lasted several days during which many of his comrades perished.

The situation in Changi was deplorable but endurable. The POWs were herded into any available space within the prison. The sleeping area allocated to him was on top of an iron grid in a passageway. In general day to day life was not too difficult, although the food and living accommodation was bad. Because of daily transportations to the Singapore dockside occasional food items could be smuggled into the camp or small food gifts from friendly Chinese would find their way in. The various nationalities imprisoned in Changi at that time were under the command of their own officers. Providing you kept your head down and kept a low profile the Japanese guards left you alone.

Then one day all the POWs were called on parade where they were told that they would be transported to another place where they would have the honour of building a railway for Emperor Hirohito of Japan. Soon after, during night time, a convoy of lorries took them to Singapore railway station where a long train of steel cattle, trucks was waiting. Prior to being herded into the trucks the POWs were told that whilst building the railway for the Emperor they would be well treated and food would be adequate providing they followed the orders given by the Japanese armed forces. In the case of non-obedience the punishment would be harsh but fair. It transpired that 'the other place' was Thailand. The train journey from Singapore to Ban-Pong in Thailand lasted several days during which it became obvious what kind of treatment they could expect from Hirohito's brave soldiers. The POWs were crammed into the steel trucks with thirty to thirty-two in each wagon which meant there was standing room only. During this journey dysentery claimed its first victims.

Soon after arriving at Ban-Pong Fred's group was transported to a large POW base camp at Kanchanaburi where the accommodation allocated to them was a long derelict bamboo hut. The roof was open to the sky in many places, the interior bamboo sleeping platforms were virtually non-existent, the allocated sleeping space on the slats was about two feet in width for each man, the floor was mud. The POWs were immediately put to work to repair their hut. During this period Fred had his first experience of the promised fair treatment from the Japanese guards which was beating prisoners across their back with a bamboo stick for no apparent reason.

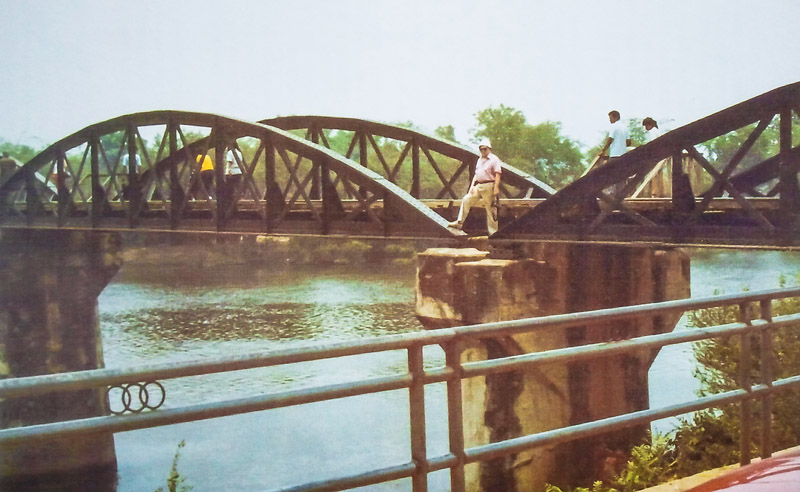

Fred started work on the railway by driving straight tree trunks into the river bed at Tamarkan, intended as the foundations for the concrete columns supporting the Kwai river bridge. He was forced to work from dawn to dusk on a meagre rice and slush diet. The entire pile driving operation was carried out without any mechanical aid. Groups of POWs were forced to stand waist deep in the river operating the ram by means of a triangular bamboo structure fitted with a pulley and a stout rope assembly. The POWs pulled and released the ram on the command of a Japanese guard standing on the river bank shouting through a megaphone the rhythm at which he wanted the POWs to operate the piling ram. Great discomfort was experienced by the POWs. Fred arrived back at camp at dusk and could hardly raise the spoon to his mouth trying to eat the rice and grey coloured slush given to the prisoners. The pain in his arms made it difficult to sleep in readiness for the next tortuous day. This exercise went on for several weeks when his group was transferred to building embankments for the railway running from Ban-Pong into Burma.

Working on the embankments in the areas where the main base camps were located the countryside was mainly flat and level. Whilst steadily moving north the terrain changed from flat to undulating, with irregular soil conditions. When building an embankment many meters high with soil alongside the track, often containing heavy boulders, then the physical difficulties in transporting the required volume of earth for each day became manifold. The building of these embankments was accomplished either by individual POWs carrying a wicker basket: filled with earth from the digging area alongside the track to the top of the ever growing embankment or by two POWs carrying a makeshift stretcher to the top. This was not too strenuous a job whilst the embankment was in its early growth stage but as the height increased so did the problems accompanying the work. Fred experienced incidents of a daily occurrence when struggling up the embankment with a heavy load on his shoulders and sinking into the loose earth and finding it impossible to move his legs because of cramp in his thigh muscles. When this happened the Japanese guard would begin shouting and hitting him with a stick with the result that somehow Fred would get moving again, if only to escape the dreaded bamboo stick.

With the advance of the embankment building Fred's group moved steadily northwards , leaving the base camps behind. They were now based in smaller camps which did not have a name but were identified by a number only. The smaller camps were always under the command of a Japanese non-commissioned officer and these creatures soon became notorious for their cruel and inhumane treatment of the prisoners. During his captivity and work on the railway in the smaller camps Fred himself underwent atrocities and witnessed many tortures carried out on fellow POWs by the Korean guards, under the command of Japanese superiors.

Definitielijst

- POW

- Prisoner of War.

Images

Cruelties

An example of the type of cruel and indefensible behaviour carried out by the Japanese happened on a day when it was Fred's turn to make his way to the Japanese cookhouse and try to find something for his group to eat. It had become known that a small Red Cross consignment of food for the POWs had been delivered to the camp. These rare Red Cross deliveries, intended for the prisoners, were always confiscated by the Japanese for their own use.

Fred managed to reach the cookhouse safely and found a small case containing tins of fruit. He took one tin. On leaving the cookhouse he was suddenly confronted by a Korean guard kicking him in the groin and crushing his rifle butt into Fred's chest. Fred was kicked and prodded by bayonet to the guardhouse where several guards assaulted him until he was in a semi-conscious state. The Japanese commander then arrived, poured a bucket of water over Fred and told him in broken English that he had committed a terrible crime by stealing property belonging to Emperor Hirohito. Fred tried to make the commander understand that he could not be a thief when the item was the prisoners' property. The commander did not accept this logic and said that the crime was punishable by death, to be carried out at sunrise.

He was taken to a tree ten yards in front of the guardhouse where he was tied by hands and feet to the trunk and a wooden bucket filled with water put on the ground in front of him. After some more face bashings he was left alone. This kind of torture is sophisticated but horrendous. It leaves no physical marks but the mental torture is indescribable because during the time that you are tied to the tree your mind tells you that your life will come to an abrupt end when the sun rises. However there is just

a small corner in your mind that tells you the commander's verdict was only delivered to create a mental torture.

Fred regained consciousness in the POW hut whilst a mate tried to make him drink some water. This kind of torture was carried out daily along the entire railway track. Soon after this experience he was back on the railway laying rails and hammering retaining spikes into the wooden sleepers.

In addition to the various tortures there was the constant threat of dying because of the total absence of medical treatment for the many diseases the prisoners contracted. POWs who were forced to bud Ld the Thai-Burma railway have suffered lifelong health problems as a result of maltreatment.

Fred suffered many illnesses, the aftermath of some remaining with him for life. The illnesses he suffered were malnutrition, chronic dysentery I malaria (of which one attack was touch and go), pellagra, the beginning of beri-beri and a small tropical ulcer on his left foot which miraculously healed. He claims this was cured by standing motionless in the river and letting tiny fish eat away the infected flesh. This treatment was only possible when the ulcer was at an early stage. In the majority of cases the wound spread rapidly to the bone. The treatment for removing puss and rotting flesh was carried out by 'medics' holding down the patient whilst one comrade removed the infect ion by scraping the wound with a sharpened spoon. If the infection was too advanced for this treatment then the infected limb had to be amputated. This was carried out by handsaw and without an aesthetic!

Probably the most feared disease was cholera and Fred experienced this at one of his camps. Overnight the huts were filled with the dead and the dying. The Japanese were terrified of this disease and hastily retreated to a safe distance, after barricading the entry to the camp with rolls of razor wire. The prisoners were instructed to incinerate the dead, not to bury them. Cholera strikes swiftly without warning and is terminal in the absence of medication. The prisoners' medical kit did not contain even an aspirin tablet. Combined with the emaciated state the prisoners were in the onslaught was terrifying. You could be OK in the morning and dead in the evening. Once dehydration set in your place on the pyre was assured. Fred was one of a team attending the funeral pyre and depositing the bodies of his friends into the flames. This was a round the clock operation,24 hours a day. It was particularly macabre and frightening at first. Bodies would suddenly sit-up, or an armour a leg extend jerkily. But even this horror soon became a routine job. The cholera epidemic vanished as suddenly as it broke out.

After the incredibly short construction period of the railway of only 16 months the two sections, leading from Burma and Thailand respectively, met inside the Thai border in October 1943. After that Fred's group was taken to the camp in Kanchanaburi for the purpose-of regrouping the remaining POWs and putting them to work in other areas of the South Pacific, including Japan. Those who were destined for Japan were herded onto the notorious hell ships in indescribable conditions. Of the 15,500 allied POWS shipped at this time approximately 11,000 perished at sea as a result of allied naval action because the Japanese ships transporting the POWs did not display signs that POWs were on board, as required by the Geneva Convention.

Fred became part of a small group destined to carry out ongoing repairs to track and bridges of the railway in the north of Thailand. These groups were small in number and never long in anyone place. Often their encampments consisted of a small clearing in the jungle or, if fortunate, a derelict abandoned camp. During the spring of 1945 Fred was digging tunnels into hillsides. These tunnels were used by the Japanese to store ammunition for their front in Burma and they were connected to the main rail track by narrow gauge rails. Fred and his comrades were surprised that the Japanese appeared to be unconcerned that the POWs-were aware of these dumps-but the reason for the lack of concern became clear later on. In a small camp just south of the Three Pagodas Pass his group was ordered to dig a deep and wide trench. On querying with the Korean guards the purpose of this trench the explanation was that Thais was a trap intended for allied tanks. Fred suspected that this was not the true purpose. Later evidence confirmed his suspicion when barrels of kerosene were found near the camp and written orders from the Japanese high command to drive the prisoners into the ditch, kill them all and set the corpses alight then fill in the ditch. The POWs concerned would have disappeared without trace.

Definitielijst

- bayonet

- Pointed weapon that can be placed at the end of a rifle and used in man-to-man combat.

- POW

- Prisoner of War.

Freedom

On the morning of the 18th August 1945 Fred went to the latrine looking for the guard, who was usually hiding in the shadows, to make the compulsory bow to him. To his surprise the guard was not to be seen. There was an unusual stillness in the camp. Fred and a mate crawled to a bush from where they could see the guardhouse. The Japanese flag which was always tied to the base of the flagpole at sundown was not there. A number of empty crates and general rubbish was strewn about and there was not a guard in sight nor any noise coming from the guardhouse.

Fred saw a look of utter amazement and bewilderment on the face of his mate, not daring to think the unthinkable. After a while they decided to approach the guardhouse from two ways, not knowing what to expect. Fred remembers clearly his heart throbbing, the palms of his hands sweating in fear. He and his mate slowly began to realize that something momentous had happened during the night. Then someone shouted "the bastards have gone" but still the fear remained that the guards would suddenly return and open fire on them until several natives came running into the camp wildly gesticulating and shouting saying that the guards had left during the night in lorries. They also told the prisoners that the unthinkable had indeed happened and that the Japanese had surrendered on the 15th August.

Pandemonium broke loose in the camp. Some just stood there quietly, tears streaming down their haggard faces. Others jumped around like mad men, shouting and yelling. Still others sank to their knees and prayed in silence. Fred remembered this incredible event with great emotion and a kind of pride. A pride at having survived a living hell for three and a half years while knowing that every hour, every day, during that period his life could end. He suddenly realized that he was a free man again. Free to say "no" to anyone and anything.

The natives took them to a small siding along the rail track where there was a locomotive and two flattop trucks. In spite of many defects Fred and his comrades managed to get a low steam pressure in the boiler after natives helped to fill the engine's water tanks and load timber which would hopefully take them several hours down the track. The sick not able to walk were carried to the flattops . Those who could still walk got the locomotive going, accompanied by alarming clanks and hissing steam from the engine. After a short while of very slow travel and crossing two small bridges Fred remembered one of the most wonderful moments of his life. Someone on the leading flattop shouted to stop the engine. Ahead of them puffing slowly round a bend came a locomotive with two Red Cross flags flying at either side of the engine's boiler. It was a Red Cross train that had left Kanchanaburi searching for POWs in the north of Thailand. It appeared that they had orders to look for them without knowing where they were as there was no administrative evidence. The rescue team had almost given up hope of finding any more survivors when they came upon Fred's group.

Fred firmly believed that this was a miracle without doubt. Sadly a few of the sick died shortly after arrival at the field hospital in Kanchanaburi. Fred was sad at being separated into groups of nationalities again because during his period as a prisoner, and in particular in the smaller camps, the question of nationality never arose. They all helped each other to stay alive. He always afterwards missed the closeness and feeling of total mutual trust among his fellow POWs. Fred's weight at the time of liberation was 5 stone 6 pounds.

It was stressed to the surviving POWs that it was essential for their well-being to remain on a starvation diet for a short while because the digestive system would not be able to process a normal diet. Sadly, however, some disregarded this advice and went outside the camp to feast on Thai food. As a consequence several died. Once the dietary restrictions were lifted and normal food was gradually introduced Fred was astonished at the quick rate of recovery.

Soon after liberation the Americans were airlifted from the base camps, the Australians were shipped home, followed by the British. The Dutch contingent to which Fred belonged was ordered by their government to remain in Thailand until further notice. Because of the native uprisings on Java and Sumatra all military personnel in Thailand were put on standby to be sent to quell the rebellions.

The situation for Fred now was that having volunteered into the Dutch army he had become a professional soldier and as such he could now be sent anywhere as directed by the military authorities. He decided that he would not obey any such orders. He learnt that if accepted by the Military Police he would not be sent to Java so he applied for a post with them and was accepted.

He was moved to a special hut with comfortable accommodation, allocated a jeep and driver, and soon found himself working in collaboration with the Thai police in fighting well organized gangsters engaged in drug dealing.

During this time he and his colleagues used to visit a Thai cafe for drinks, snacks and to exchange news. The owner of the care had a little girl who had stolen their hearts, in particular Fred's. Suddenly this little girl fell seriously ill. The Thai doctor treating her said that he did not have the necessary drugs and that without them she would die. Fred and his friends dragged their own doctor to the cafe to examine this little girl and he agreed with the diagnosis of the Thai doctor. The drugs were available to the military but under rules at the time could not be given to the Thai population. However Fred understood the 'wink and nod' and he became a 'thief' once more. A course of drugs was given to the girl who made a complete recovery. Fred felt it was a small 'thank you' to those Thai people who had put their lives on the line in trying to help the POWs whenever they could.

After a while the gangster activities abated and life became one of daily routine. In the latter half of April 1946 the remaining Dutch exPOWs still in Thailand were transported to Bangkok where they embarked on to a Dutch passenger liner, the Nieuwe Holland, bound for Amsterdam. AT LAST!

During the journey home Fred realised that for many exPOWs their ordeal was not over, in spite of their new found freedom. The mental scars would remain with them for the rest of their lives. There were some who could not handle the return to civilian life and committed suicide by jumping overboard. Fred believed that the two reasons for surviving his time as a POW were his determination to see his fiancé again and his total belief that the Japanese would be defeated.

Definitielijst

- collaboration

- Cooperation of the people with the occupying forces, more generally spoken the term for individuals who cooperate with the occupying force is collaborator.

- POW

- Prisoner of War.

Images

Coming home

The arrival at IJmuiden (port for Amsterdam) was a complete anti-climax with regard to the reception Fred and his comrades received from the Dut.eh authorities. When the ship arrived in Dutch waters it reduced speed in order to arrive in port during night hours. There were no officials to welcome their countrymen home. No brassband playing. No relatives on the quayside. The military were put into buses and driven to the Harskamp, a military encampment in the centre of Holland, where they were billeted in army tents with room for four persons in each.

Several days later they were told that all military personnel would be demobbed. After receiving the outstanding back pay from the army there was a table to the right of the paymaster where a man in a grey suit declared that Fred owed him 10% of his back pay for income tax. At that moment Fred made up his mind that he wanted to leave Holland as soon as possible. Following the pay he was given a set of second-hand clothing in exchange for his military uniform.

Although Fred's parents had been informed by the authorities of their son's arrival in Holland they were not told when to expect him. He was taken by coach to his home town, Rotterdam, not outside his parent's home but some streets away. He remembered After leaving the coach he felt like a stranger in a foreign place. He even had to ask a passerby where the street of his parent's home was located.

His welcome at his home from his parents and eldest sister was not what he had hoped for after an absence of 7 years, since going back to sea in 1938. The welcoming situation was one of disappointment and bewilderment on both sides. Fred learnt that his parents had not received the one card he was allowed to send whilst a POW in Thailand. In the absence of any news during all those years his family had come to believe that he had perished, either at sea or as a POW. From the moment he entered his parent ' s home he felt uncomfortable and claustrophobic. He immediately began the difficult process of travelling to England with the view of finding a sui table occupation and beginning a new life. Six weeks After his arrival in Holland Fred was united with his fiancé in England. The welcome he received from her was a shock although he did not realize it at the time and it would only become clear in years to come.

Fred settled in Grays, Essex, not quite knowing what the future for him would hold. He had a letter from a doctor in Holland to hand to an English doctor. This said he should under no circumstances seek work for at least a year and that he should report to the Hospital for Tropical Diseases in London, which he attended at three monthly intervals during that year.

Fred was married to Edna in August 1946. None of his family or friends were present at the wedding. Edna worked full time as a manageress of a local catering company and as such was the only earner. Her job demanded that she was in the office during daytime and working most evenings supervising functions. It was painful for him to realize that his wife was keeping him. Because of the home situation he soon began to feel lonely and isolated.

In time Fred began to make friends who became concerned about his well-being as he had problems in returning to civilized living. He had inexplicable bouts of anger and became visibly frightened when meeting strangers. After seeking medical advice ne attended a psychiatrist in London for a year after which he was ready to go forward with his life.

The main reason for him being allowed by the British authorities to settle and work in England was because of his engineering qualifications. He was given to understand that he would have no problem in finding sui table employment. This, however, was far from what actually followed. Any job that Fred considered suitable and he applied for always ended at the interview "By the way, what is your accent?". And then "Sorry, British only". Fred eventually found a job as a ships' fitter. In 1949 their daughter Melanie was born.

A period now began when Fred faced the experience of being an immigrant. Because of his training as a marine engineer he soon became popular with the company's management. This resulted in hostilities from his workmates and culminated in unacceptable abuse from a Union spokesman. He left the job to start work as a maintenance fitter at a large oil storage establishment at Thames Haven (Essex).Definitielijst

- POW

- Prisoner of War.

Career

He found the work there pleasant and interesting and soon made his mark by taking on some work that was usually contracted out for repair purposes. He earned the respect of his work colleagues and made several friends. After about a year the foreman of the engineering repair section was retiring. The management were keen that are placement should be sought from the interior workforce or from the neighbouring Shell refinery. To Fred' s surprise the foreman entered his name on the list of applicants and to his even greater surprise Fred learned that the entire maintenance staff at the Thames Haven works had recommended that he should take over from the retiring foreman.

The job of foreman of the engineering shop was one of importance to the company. With the job came a company house and car expenses. The possibility of obtaining such a job was exciting and satisfying to Fred because he felt that he would again become a useful member of society. He discovered, however, that if he was selected for the job he would have to move to the company house which was located about one mile from the job site and his wife made it quite clear that she would not move from their house in Grays.

However prejudice and ignorance struck once again. Fred had already had a typical experience of the Union power which was established in factories all along the river front from Southend to London. Now, when the Amalgamated Engineering Union representative at the Shell plant, whose name also appeared on the vacancy list, heard of the plan to promote Fred he started a campaign - aided and abetted by Union officials - to have Fred's name removed from the list because Fred was non-British and therefore should not be given a job of management status. Fred being a Union member, by virtue of being compelled to, fought hard against this unfair attitude. It was to no avail and the Shell Union representative got the job. Fred immediately resigned from the company, disillusioned and downhearted. He applied for another maintenance fitter job at a factory closer to home.

This company operated a non-Union workforce in as much that those who wished to belong to a Union could do so as long as they accepted company rules. The wages were the highest in the area, with excellent work and welfare conditions. Fred was offered a job from a long list of applicants. The factory was only ten minutes ride by motorbike from his home. Here once again, because of his engineering background, he was soon allocated to important jobs. He was recognised as an effective maintenance fitter, without any prejudice from his work colleagues.

In a few years Fred was given the responsibility for the maintenance of a new processing plant. This offered an increase in basic pay but with the need to be on call-out twenty four hours a day. When the company extended their works by adding a new processing facility, including hither to unfamiliar machinery, Fred was given the job of installing and test running the new plant. He remembered the satisfaction and pride he felt that the company had given him this important job.

After some ten years of employment Fred felt that the time had come to advance his career further and to get away from manual engineering. He seized his chance by applying for the job of a draughtsman wi thin the company and believed he would get it. However, to his dismay, a colleague was offered the job. The reason for not getting the job was explained to him in terms that he was more important to the company in his present position. Fred resigned to look further afield to fulfil his ambition to get away from manual engineering. To achieve this he realized that he had to look to London where the large engineering employers were situated.

Within a short while of leaving Fred was employed by a large engineering company in London specializing in building grass root oil refineries and electricity generating power plants. This meant daily commuting from Grays, making a twelve hour day from home.. After initial training he was sent around the country to ensure that equipment deliveries to the various worksites were maintained. This meant being on the road from Monday to Friday and only home at weekends. Although the work was strenuous and involved long working hours he enjoyed the job as it meant responsibility and often on the spot decision making. In the meantime Fred was divorced in 1966 from his wife Edna after 20 years of marriage.

After a while he was promoted to Expeditor Inspector. Over the years he made steady progress, became an Inspector and was eventually appointed as a kind of troubleshooter. His work involved many visits to countries abroad. Fred became a popular member of the company's engineering staff. However, After completing important negotiations with a U.K. steel manufacturer, he discovered that his report, intended for management, was taken over by a senior colleague who claimed credit for Fred's achievement.

At this time the manager of the Fired Heater Division was appointed Managing Director of a newly opened branch of an American company. This company supplied fired heaters to oil refineries. He offered Fred the job of Contract Engineer at a salary almost double what he had been earning and in view of the fact that this offer appeared to have career advancement opportunities Fred decided to join the new company.

Because Fred's new employer was based in East Sheen, south west London, this meant even longer journeys to and from work and because of marital problems Fred moved into lodgings closer to his office. He met Elizabeth. They initially became friends, friendship soon grew into love and they decided to live together. Firstly in rented rooms in East Sheen and then in their own maisonette in Richmond. They were married in January 1972. The new company initially went from strength to strength and Fred felt great satisfaction in the work he was doing. It soon transpired, however, that the higher salary he had been offered was purely a ruse to encourage him to join the company. The expected salary increments did not appear and worse was to happen. After a visit from a director of the parent company in America the London branch folded and Fred was made redundant.

He was able to find new employment with another engineering company based in central London and began working for them in early 1971. This company specialized in supplying oil refineries with sulphur recovery plant. The work Fred dealt with was varied and interesting, particularly on one occasion when he was sent to Vienna to oversee the installation of a sulphur recovery plant at the only oil refinery in Austria. He recalled the satisfaction when he was responsible for finding a fault in a turbine which was preventing the plant from going on stream. But once again disaster struck. At the time that the French left Algeria the company had won a contract with the main Algerian oil refinery to refurbish and modernize equipment. Because of the political instability in Algeria at that time the job eventually became a burden on the company's financial resources and it subsequently folded. Once again Fred found himself made redundant.

By now Fred had begun to wonder whether he would ever again be able to obtain permanent employment in the engineering industry. He decided to try self-employment and bought a franchise in a business for exterior house maintenance. In order to buy the franchise he had to use his life savings. One of the main reasons Fred entered this unknown territory was that the other participants in the scheme were all people of business experience. The owner was an Argentinean, married to an English woman, and had lived in the UK for many years. Fred worked hard at the new venture and felt that he was gradually gaining confidence and obtaining contracts. Business increased steadily to a point that he needed to employ assistants.

The franchise system called for regular meetings at the owner's Loridon office. On one of these occasions Fred arrived to find several franchise participants standing outside the office with a note stating that the office was closed. To the horror of everyone i t was discovered that the owner and his family had moved back to Argentina taking all the proceeds of the company.Two members of the group decided to start legal proceedings to recover their money but it became clear that their task would be futile. Efforts to trace the owner in Argentina were also a failure.

This period in Fred's life was a very low point as he again became a person without a job and felt humiliated every time he went to collect his unemployment benefit. He still felt that a return to engineering would not be viable in the long term. In desperation he looked for a job on the information board at the Unemployment Office and started work on a commission basis selling double glazing. This meant that every evening and weekends he was visiting potential customers but he could not make an adequate living and left, again looking for work. He now joined a company selling sophisticated massage equipment to sports people, hospitals and customers in their homes and this again meant working evenings and weekends. He found he could not apply the 'hard sell' type of selling method, was unable to reach a satisfactory sales target and decided to leave.

Deciding to try again to find employment in the engineering field he found a company specializing in industrial and domestic water treatment. He worked in the drawing office, setting out schemes for potential clients. The salary offered was well below the earnings he was used to in previous engineering jobs and the work was undemanding. After about a year Fred could no longer stand the boredom of the job. Also he was given more and more responsible work without additional benefit.

He applied for an advertised engineering job in Hounslow, Middlesex and got it. At that time, 1975, Fred was sixty years of age. He started work as a Contract Engineer. Over the years he steadily advanced to Contract Manager and finally Project Manager. The company specialized in medium capital projects, ranging from a single item to a complete plant. Fred found the work challenging and of great professional interest because every job was based on concept to final handover.

The main engineering business was the design and installation of inert gas equipment for oil tankers worldwide. The company also specialized in their patented industrial dust recovery plant and Fred was in charge of the building of one of these plants for the Greater London Authority in Wandsworth. The most prestigious job that he handled was a complete updating of the ventilating system in the other hither Tunnel, London. The job finished within budget and ahead of time.

Retirement

When Fred reached the official retiring age of sixty five the company asked him whether he would like to stay until the age of seventy and Fred accepted the offer with enthusiasm because he did not feel ready for retirement. During his latter years he designed a combined system of bar charts and graphs showing main project activities such as budget, contract duration etc. on the basis of program, progress, workforce etc. This system showed program schedules and actual achievements on a weekly basis and proved a success.

In 1983 Liz and Fred went on holiday to the Far East, visiting Singapore, Bangkok, Hong Kong (including a one day trip to China) and Penang. While staying in Bangkok they went to the Kwai River bridge at Tamarkan and the allied war cemetery at Kanchanaburi, an upsetting and emotional experience for Fred.

Fred retired at the age of seventy in 1985. His retirement party was a very special occasion as Liz had secretly organised a celebration lunch at a nearby hotel. When Liz and he arrived there he thought it would be a private family celebration but instead he found a large room filled with friends and work colleagues. It was a tremendous success.

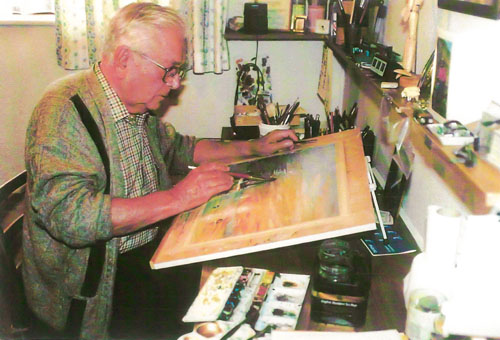

In October 1987 Liz and Fred moved to Worcester. After a period of settling in he began to think about retirement activities and he went to watercolour painting classes at Bevere Vivis in Worcester. He discovered that he had a talent for this and his work was regularly sold in the Bevere gallery and at many other local venues. In 1991 he had an exhibition of his work in the auditorium of the Swan Theatre and in 1993 a special exhibition at Bevere's gallery.

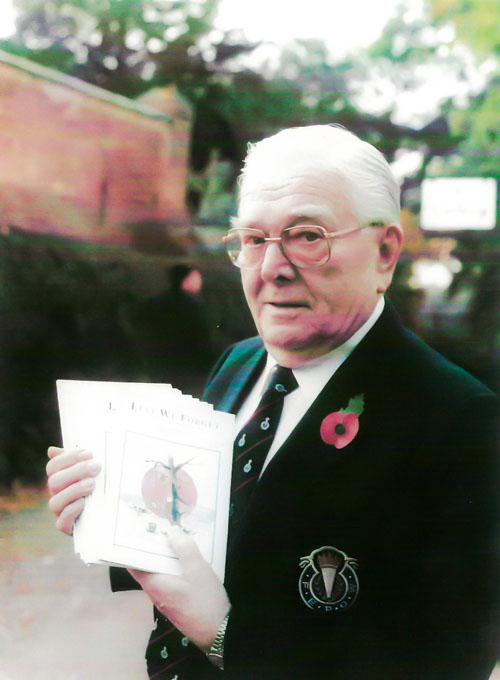

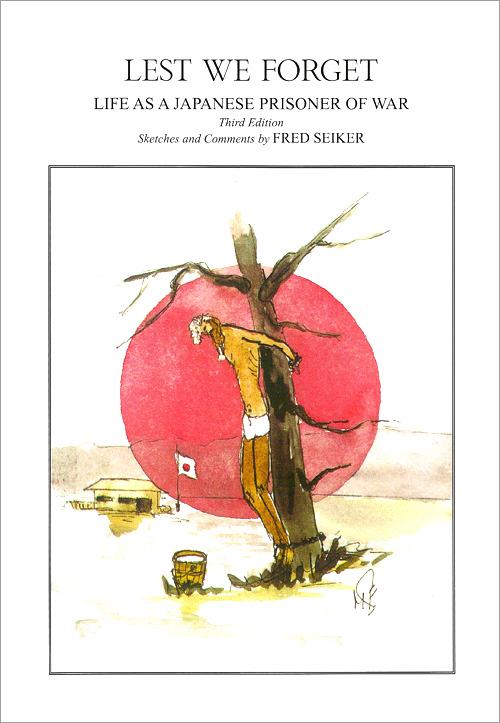

15th August 1995 was the fiftieth anniversary of the ending of World War II. During the fifty years the war in the West had been well covered by historians and the media whilst the war in the Far East had been consistently ignored. In the spring of 1995 Fred began to think of ways to make the public aware of what had happened in the Far East. He decided rather than putting his thoughts into words he would produce watercolour sketches of his own experiences and incidents he had witnessed as a POW of the Japanese. He sat down one day and started to draw a few images showing atrocities carried out by the Japanese and other events the prisoners had endured. Liz was greatly affected when she saw the simple line pictures Fred produced. As he proceeded with his sketches the memory gates opened and incidents long forgotten flooded back. It took several weeks before he finished his collection during which period he became emotionally affected and had to stop drawing from time to time.

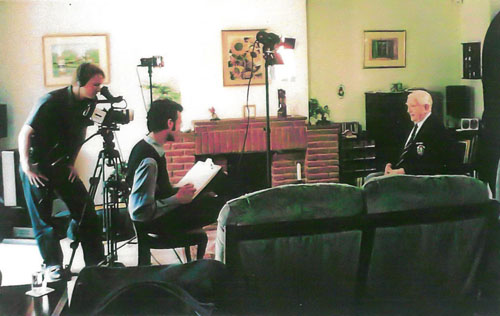

When Fred showed his collection to Bevere Gallery they suggested that he put it on show during the August anniversary. The exhibition raised an interest far beyond Fred's expectations and television, radio and press gave it full coverage. There was also a psychological impact on Fred during this time and when BBC television visited his home to interview him it was the first time he talked freely of his experiences in fifty years.

People had come from far and wide to view the exhibition and when it was over the Gallery owners suggested that Fred's pictures should be published in the form of a book. Consequently a publishing company was formed by the name of Bevere Vivis Gallery Books and Fred named the book Lest We Forget. The book was launched in November 1995 from the Gallery, with good media coverage and a book signing at W.H. Smith in Worcester. To Fred's delight several members of the Birmingham FEPOW (Far East Prisoners of War Association) attended the launch and soon after Fred became a member of FEPOW.

To reach a wider public it was decided to advertise the book Lest We Forget on the internet and this was done by the Gallery. The effect was immediate on a worldwide scale, producing many emotional E-mails from people who visited the website.

During the ten years 1995 to 2005 Fred suffered a deterioration in his health and it annoyed him greatly when he was unable to attack life with his usual vitality. He had two hernia operations, a replacement hip operation and is now troubled with the carpal tunnel nerve in one wrist. He developed Meniere's syndrome and tinnitus, was found to have fibrosis in both lungs and has ongoing diverticular disease. Arthritis has been painful in many parts of his body and gets worse. He has had several breathing attacks necessitating three urgent visits to A&E by ambulance and now has oxygen by his bed for emergencies. Despite all these problems, together with health problems by being a POW, strangers take him to be 15 years younger than his actual age.

Fred took any and every opportunity from 1995 onwards to make known the story of the allied prisoners of the Japanese in World War II, particularly he wanted to inform the younger generation so that they could be aware of what so easily could happen again. He donated any fees given to him to charities. The following are some of his activities.

Fred Seiker passed away in his home on June 2nd, 2017 at the age of 101.

Definitielijst

- POW

- Prisoner of War.

Images

Publicity of Lest We Forget

The story of Lest We Forget and paintings can be found at: Fred Seiker, Lest We Forget

The book can be found at the Imperial War Museum in London, the Imperial War Museum North in Manchester, the National Memorial Arboretum at Alrewas, the Second World War Experience Centre in Leeds, Eden Camp in Yorkshire, the Nimitz Museum, Fredriksberg, USA and various other venues.

In October 1997 Fred was invited to speak to a meeting in London of a group formed to promote and commemorate the story of the Thai-Burma railway. Local dignitaries were invited, including the Mayor and Mayoress of Westminster and following the meeting his talk was put on the internet. He has given the talk in the UK tb various institutions and organisations including schools, Probus, and Rotary groups, U3A, Worcester University and the Royal British Legion. Abroad he lectured in Japan and the USA.

Fred's talk and his book have been translated into the Japanese language by Akira Tanzawa and Koshi Kobayashi respectively. This has been of great satisfaction to Fred as it has meant that the Japanese people would learn something about the war which had previously been withheld from them.

His book and transcript of his talk are in the HelI Fire Passmuseum and the information centre at Kanchanaburi, both in Thailand. Professor Pasternack of the University of California, USA requested Fred's permission to use his talk in a series of lectures programmed for the autumn 2005 semester at the university.

Correspondence with VIPs

Prime Minister John Major, Prime Minister Tony Blair, Prince Philip, Prince Charles, Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands, President Clinton, Japanese Ambassador in London, Japanese Foreign Minister in Tokyo, Director of Imperial War Museum in London, Director of Imperial War Museum North in Manchester, Military Attaché at Netherlands Embassy in London, British Embassy in Bangkok, Royal British Legion in London.

Media and other interviews

Fred has been interviewed by national and local radio, television and press in the UK, the Netherlands, USA and Japan. Also the Records Office of Hereford and Worcester County Council and the Second World War Experience Centre in Leeds. His story Smile from his book, and his talk, have been recorded on audio tape by the Royal National Institute for the Blind for their talking books project.

Written articles and stories

He has written articles for the Merchant Navy Association, corporate organisations and USA magazines.

Two of his poems - 48 Hours Leave and Bill - have been published by Poetry Now of Peterborough. The first poem is set in wartime Britain, the second is a tribute to a dying comrade whilst a POW.

Documentaries

Fred is a contributor in the documentaries:

The True Story Of The Bridge On The River Kwai made by Greystone Communications of Hollywood, USA.

Hell In The Pacific produced by Carlton TV, UK.

Japan's Prisoners Of War produced by the History Channel.

The Bridge On The River Kwai - The Documentary made for National

Geographic, USA.

An extract from the story Smile in his book is used in a documentary by Irish Promedia TV, Dublin entitled Surviving The Sword.

Foreign visits

In 1998 Fred was approached by Keiko Holmes of Agape, an organisation to encourage reconciliation between exPOWs and Japanese people. She invited him and Liz to attend the annual meeting between Japanese Agape members and exPOWs in London that summer. During a visit to the Japanese Embassy Fred was pleased to have a long and interesting conversation with the Ambassador.

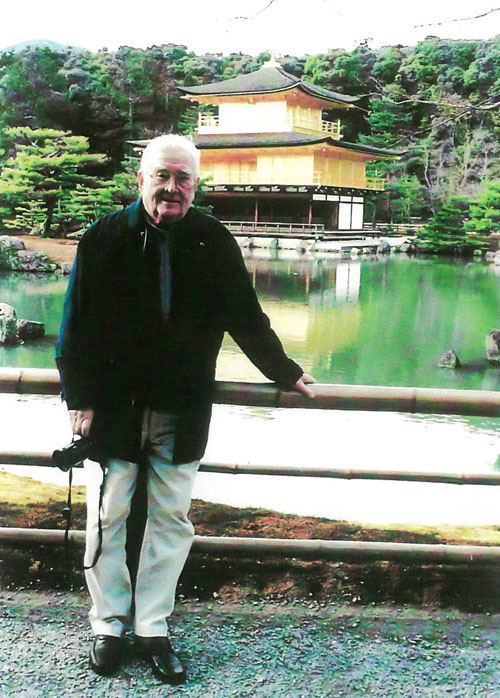

The following year Fred and Liz were invited by Keiko Holmes to travel with a group of exPOWs to Japan on a reconciliation pilgrimage. They found the people they met welcoming and friendly. However, whilst visiting the, atomic museum in Nagasaki Fred became angry that the reason for dropping the atomic bomb on that city was presented by the Japanese in such a way that the Americans were made to appear the aggressors and that the dropping of the bomb was totally unnecessary. Fred was approached by reporters from a leading Japanese national newspaper and national television. He agreed to be interviewed provided that the views he expressed were truthfully represented. The interview was shown on television that evening, also a report appeared in the press, and according to an interpreter the media kept their word.

Fred had made contact with Val Roberts-Poss, the Executive Director of the USS Houston Survivors Association & Next Generation. As a result in 2000 he and Liz attended the annual commemoration service in Houston, Texas, USA of the cruiser USS Houston which was sunk by the Japanese during the battle of the Java Sea. Survivors from the ship were taken prisoner by the Japanese and transported to the Thai/Burma railway.

National Memorial Arboretum, Alrewas, Staffordshire

In 2002 two memorable events took place connected with the installation of an original section of the Thai/Burma rail track. Fred was invited by the BBC to attend the actual arrival of the rail track. He and Liz were driven by taxi to the Arboretum and Fred found himself standing in a wet and foggy field at 7am being interviewed for BBC World Service and the Breakfast TV programme. For the rest of the day representatives of the media were queuing to interview him and he found the experience emotionally and physically exhausting. There was a slight hitch in the arrival of the track which did not arrive until late afternoon. When the track was eventually unloaded the emotion experienced by Fred and his comrades was overwhelming.

The second memorable event was when Fred was invited to meet Prince Charles who was visiting the Arboretum and interested in viewing the rail track. The Prince listened with great interest to what Fred had to say and showed obvious signs of sympathy with the plight of the POWs. Fred felt very honoured later to receive a personal letter from the Prince, a copy of which is on display at the Arboretum beside his pictures.

Fred and Liz became Friends of the Arboretum and have donated a bench and a tree, which are sited alongside the rail track, also an electric scooter for the use of invalid visitors.

In early 2013 Fred moved his original painting collection Lest We Forget to the Bronbeek Museum, Arnhem, The Netherlands.

Memberships

Fred is a member of the Royal British Legion, Merchant Navy Association, FEPO (Far East Prisoners of War Association), Friend of the National Memorial Arboretum and an honorary member of the USS Houston Survivor's Association.

Other events

He is responsible for having a memorial plaque installed at the Eden Camp museum in Yorkshire commemorating those who perished during the construction of the Thai-Burma railway. Copies of his watercolour paintings as depicted in his book are used in display panels in hut 10 at the museum.

His name is inscribed on a memorial monument in Hirado, Japan, because of his involvement with the International Relations Organisation based in Hirado.

In 2001 Fred was presented with a campaign medal of the Netherlands army in Indonesia during WWII. The medal was presented at his home in Worcester, some 60 years late, by the Military Attaché from the Netherlands Embassy in London, his Adjutant and a representative of the Royal Netherlands Navy.

Fred has been and always will be willing to help in anything to do with the POW scene. Requests are diverse and arrive unexpectedly by letter, phone, Email or FAX from all over the world. Many come from those searching for information of loved ones who perished on the Thai-Burma railway. Recently a university student stayed with Fred and Liz while doing research on POWs for her dissertation - she was particularly interested in anything relating to her now deceased grandfather who had been a POW on the railway.

A most memorable occasion took place in August 2005 during the 60th anniversary commemorations of VJ Day at the Cenotaph in Whitehall, London. The BBC approached Fred asking for permission to use a poem he had written in memory of a dying friend whilst a POW.

The BBC intended to use the poem as a closing item of their TV broadcast. Fred agreed and his poem was read by the commentator James Naughtie, with a credit to Fred by name. It was a fitting and moving end to the ceremony and Fred felt very proud at being able to contribute to this important national occasion.

Definitielijst

- cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

- Nagasaki

- Japanese city on which the United States dropped the second atomic bomb on 9 August 1945.

- POW

- Prisoner of War.

Images

Information

- Published by:

- Ewoud van Eig

- Published on:

- 20-03-2013

- Last edit on:

- 21-11-2023

- Feedback?

- Send it!