Abraham Asscher (1880-1950)

Abraham Asscher was born in Amsterdam on 19th September 1880. His father and uncle worked in the diamond trade and founded a company together, the Diamantmaatschappij. Later, Abraham Asscher became the director of the company and its only shareholder. Under his leadership, the business gained a worldwide reputation. The absolute pinnacle of Asscherâs diamond factory would surely have been the cutting of the Cullinan diamond, the largest diamond ever discovered.

From an early age, Asscher belonged to the Jewish religious elite, although he was by no means orthodox since he only visited the synagogue on religious holidays. His political involvement was evidently greater than his religious commitment. At a young age, he became the leader of the Liberal State Party (Liberale Staatspartij) and was a member of the States-Provincial in North Holland in 1917. As was usual for members of the Jewish elite, Asscher had an aversion to socialism, a political movement that had a large following among the Jewish proletariat. As an important industrialist and prominent politician, he was a man of status in Amsterdam and was connected to almost all of the significant Jewish institutions and committees. Asscher always did things on a grand scale. He loved to give speeches in theatres packed full of important people in the audience. As a governor and representative of the Jewish community, he succeeded Mr. Dünner as the leader of the Dutch-Israelite Church Association, the umbrella organisation of the Jewish councils in the Netherlands. He was also a governing member on the council of the biggest member organisation of this association, the Dutch-Israelite Main Synagogue in Amsterdam. In addition, Asscher was on the board of Keren Hayesod, a fundraising organisation for Palestine. Because of his great achievements, he was made a Knight of the Order of the Netherlands Lion in 1935. He received the honour in the presence of prominent members of the Dutch political and governing world.

David Cohen was a member of several of these organisations. Asscher worked with him predominantly on the Committee for Special Jewish Interests, an organisation with many divisions such as the most important, the Committee for Jewish Refugees. The committee assisted German Jews and warned of the dangers of national socialism. In the years between 1941 and 1943, Cohen and Asscher were both chairmen of the Jewish Council.

The German occupiers appointed Asscher and Cohen as chairmen of the Jewish Council in 1941. Both Jewish leaders approached the task with the sincere conviction that they could make the best of a bad situation or at least delay the process so that Jews would have the time to flee or to go into hiding. Initially, the Jewish Council's tasks were limited to Jews in Amsterdam but their tasks were rapidly expanded on a national scale. Unwittingly, the Jewish Council became an important instrument in the deportation of Dutch Jews. After the war, both chairmen were held accountable for their involvement in the Jewish Council.

Asscher, whose wife had died in 1940, was deported to Westerbork in 1943 and then onwards to Bergen-Belsen on 13th September 1944, where he was liberated in 1945. After the war, the Jewish Honour Council found Asscher and Cohen guilty of reprehensible actions. They were found guilty of what happened to Dutch Jews during the war and they were forbidden from working in any Jewish organisation again. Asscher was so insulted that he cancelled his membership to every Jewish organisation. Abraham Asscher died on 2nd May 1950 in Amsterdam. As a final protest, he did not ask to be buried in the Jewish cemetery in Muiderburg but rather in a general cemetery, Zorgvlied in Amsterdam. Hundreds of people attended his burial but among them was not one representative of the Jewish community.

An evaluation of the Jewish Councilâs conduct and its later condemnation by the Jewish Honour Council is provided in more detail in the article about David Cohen.

Definitielijst

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- national socialism

- A political ideology drawn up by Hitler based on the superiority of the German race, the leader principle and fierce nationalism that was fed by the hard Peace of Versailles. National socialism was anti-democratic and racist. The doctrine was elaborated in Mein Kampf and organised in the NSDAP. From 1933 to 1945 National socialism was the basis of totalitarian Germany.

- socialism

- Political ideology aiming at slight or no class differences. Means of production are owned by the state. Evolved as a response to capitalism. Karl Marx tried to substantiate socialism scientific.

- synagogue

- Jewish house of prayer.

Images

Abraham Asscher was a diamantaire, politician and, during the war, one of the two chairman of the Jewish Council. Source: Beeldbank WO2.

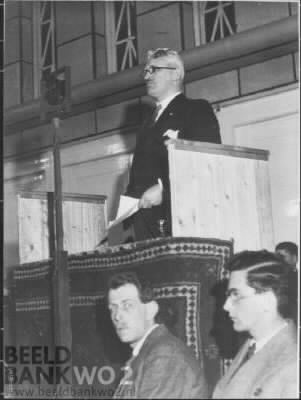

Abraham Asscher was a diamantaire, politician and, during the war, one of the two chairman of the Jewish Council. Source: Beeldbank WO2. Asscher at a meeting opposing the Neuremburg laws as part of the Committee for Special Jewish Interests (established on 21st March 1933). Source: Beeldbank WO2.

Asscher at a meeting opposing the Neuremburg laws as part of the Committee for Special Jewish Interests (established on 21st March 1933). Source: Beeldbank WO2.Information

- Article by:

- Frans van den Muijsenberg

- Article by:

- Rachael Darwin

- Published on:

- 19-01-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Related books

Sources

- BERKLEY, K.P.L., Overzicht van het ontstaan, Amsterdam, 1945.

- HERZBERG, A.J., Kroniek der Jodenvervolging 1940-1945, Meulenhoff, Amsterdam.

- KNOOP, H., De Joodsche Raad, Amsterdam, 1983.

- PRESSER, J., Ondergang, Aspekt, Soesterberg, 2005.

- VELD, N.K.C.A. IN ÂT, De Joodsche Eereraad, SDU Uitgeverij, Den Haag, 1989.