Introduction

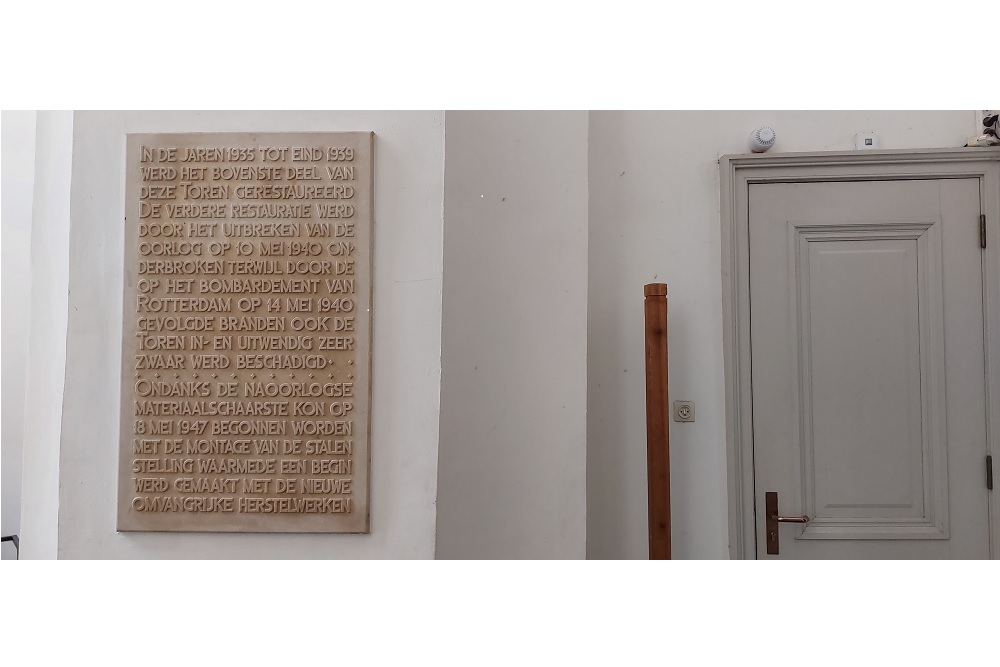

After the German invasion in the Netherlands on the early morning of May 10th, the situation for the Dutch army had deteriorated fast. On the Friesian side of the "Afsluitdijk", (enclosing dyke, that separated the former Zuiderzee from the North sea) they managed to hold their positions. On the Grebbeline too, attack after attack by the Germans was pushed back with much effort. The greater part of the German airborne troops were either destroyed or surrounded. A more serious danger was that German parachutists gained control over the Moerdijk bridges and that the 9e Panzerdivision (9th Armoured Division) proceeded in that direction by way of Noord Brabant. Eventually the struggle in Holland would be settled by a bombardment of Rotterdam.

Previous history

To open up the fortress of Holland for a rapid transit of the 9th Armoured Division, the Germans devised a plan in which the "7e Fliegerdivision" (7th airborne division) of Lieutenant General Kurt Student should gain control of the undamaged bridges of Rotterdam, Dordrecht and Moerdijk, which gave access to the heart of the Dutch defence (see Airdrops in the Fortress Holland). At Moerdijk and Dordrecht, the Germans succeeded in remaining in control of the bridges until the advancing 9th Armoured Division, and in her wake, the XXXIX Army Corps brought the necessary relief. Quite different was the situation in Rotterdam. In spite of the fact that German airborne troops controlled almost the entire southern side of Rotterdam, including the strategically situated Noordereiland (the island in the middle of the Maas river that divides the two city parts), the Dutch managed, mostly by the efforts of three sections of marines under the command of captain Schuiling, to keep the Maas bridge effectively under fire, so that a German crossing would likely result in considerable punishment.

May 14th 1940

On the 14th of May, tanks of the German 9th Armoured Divison (Major General Alfred Ritter von Hubicky) and units of the "SS-Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler" (Hitler's lifeguard, Dietrich) had already advanced into the southern part of Rotterdam. The commander of the XXXIX Army Corps, General Schmidt, had set up his headquarters in Rijsoord. These units stood under the direct orders of General G.K.F.W. von Küchler of the 18th army. On May 13th, at 17:05 hrs., this commander received an order from high command to break the Dutch resistance in Rotterdam with all means available. If necessary by threatening to carry out the destruction of the city. For Schmidt, one matter was obvious: a possible artillery or air bombardment had to be as limited as possible, as the German tanks needed room to manoeuvre in case fighting would break out in the city.

Negotiations had been started in Rotterdam after the presentation of the first ultimatum by the Germans. This first ultimatum had been received by the Dutch commander of Rotterdam, Colonel Scharroo. Therein he was threatened with the destruction of the city if no surrender would follow. The impression had been given that an artillery bombardment would take place, followed by an air bombardment. Meanwhile in Germany the bombers were already allowed to take off.

German negotiators Hauptmann Raimund Hörst, with Plutzar and Pessendorfer after meeting with Kolonel Scharroo. Source: Public Domain (unknown)

Scharroo, supported by General Henry Winkelman (commander in chief of the Dutch forces) did not see any reason for surrender. They considered the ultimatum; an untidy, handwritten slip of paper, as well as being unsigned (the note was closed with, "the commander of the German forces"). The German negotiator was sent back with the request to return with an official document. Since May 11th, Scharroo had received reinforcements of no less than five battalions. In spite of the numerical superiority he did not succeed in driving the German forces back. Winkelman then ordered Colonel Wilson and two other staff officers to Rotterdam with the command to - if necessary - relieve Colonel Scharroo and take over command.

Once he arrived, Colonel Wilson could not but conclude that Scharroo could not have acted differently than he had done. Too many Dutch troops had to be deployed to guard the city against possible attacks from northern, eastern and western directions due to the many scattered parachutist troops at large in the area and operations against the alleged actions of the Fifth Column.

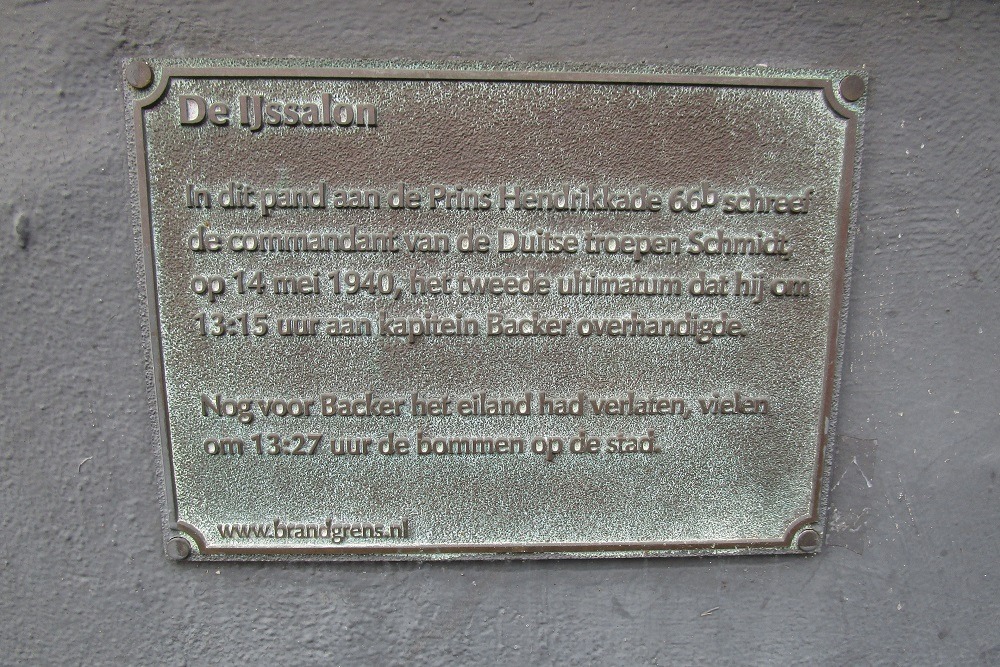

Since on German side the impression was raised that the Dutch commander was prepared to negotiate, Schmidt had sent a radio message to postpone the planned bombardment. He was informed, however, that the bombers were already underway and radio communications were no longer possible. The bombers could only be stopped by means of red flares. Colonel Scharroo sent Captain Backer to the demarcation line to receive the new ultimatum. This newly drafted ultimatum was handed over to him at 13:20 hrs., after which he returned to Scharroo's Headquarters. Schmidt allowed the Dutch three hours to answer. It should reach Schmidt at 16:20 hrs. Backer was accompanied by two German officers.

At this very moment the Heinkels approached the city. Even the German commander did not expect them so soon and was duly surprised. Immediately he had flares fired to stop the bombers from dropping their load.

Air fleet under way

At the Luftwaffe headquarters they were not aware of the negotiations. As Oberbefehlshaber der Luftwaffe (commander in chief of the air force), Hermann Göring was very anxious about the position of his 22e Luftlandedivision (22th airborne division). He was convinced that the situation in Rotterdam could only be solved by an air bombardment. Adolf Hitler, as Oberster Befehlshaber der Wehrmacht (supreme commander of the armed forces), had also announced that Dutch resistance had to be broken at any price.

Eventually the high command gave the order to Kampfgeschwader (battle squadron) 54 to take off. At 11:45 hrs. 90 Heinkels He 111 bombers took off from Delmenhorst, Münster and Quackenbrück, with destination Rotterdam. The unit was divided in two groups: Oberst (colonel) Wilhelm Lackner commanded a group of 54 Heinkels, whereas Oberstleutnant (lieutenant colonel) Otto Höhne commanded the remaining 36. The planning was that the aircraft would arrive over Rotterdam at 13:20 hrs.

The aircraft commanders knew that in case the bombardment was postponed, red flares would be fired. The message of Schmidt reached General Kesselring at 12:35 hrs. The squadron of Oberstleutnant Otto Höhne saw the flares and broke off the attack. The group of Oberst Wilhelm Lackner, approaching from the east, continued and dropped their bombs on the city.

The bombardment

In Rotterdam the air raid warning was given. A great number of people fled into shelters, laid down on the street or pressed themselves against the facades of large buildings. In a quarter of an hour time 158 bombs of 250 kg and 1150 bombs of 50 kg fell down on the city. The damage was enormous. Connections fell out, houses caught fire. The fire spread so fast that the entire heart of the city was reduced to rubble. When the smoke cleared on May 15th, one could take stock. About 800 people were killed. Over 80.000 people lost their homes and 24.000 houses were lost.

At 15:00 hrs. Colonel Scharroo ordered his sub commanders to cease fire. At 15:50 hrs. he offered the surrender of Rotterdam to General Schmidt, with the approval of the representative of General Winkelman, Lieutenant Colonel Wilson. At 15:30 hrs. Wilson arrived at the General Headquarters of General Winkelman at The Hague. "I'm coming from hell", he said and told that Rotterdam had been bombed, was on fire and had surrendered. Winkelman was shocked, but not prepared to issue immediate orders for total capitulation.

Meanwhile Scharroo was on his way to inform his troops of the intended surrender. Due to the bombardment so many roads were blocked that he was not able to reach his headquarters until 18:30. In the meantime, Göring lost patience and ordered a new a bombardment on Rotterdam. A second wave of bombers took off around 15:30 and would reach Rotterdam somewhere around 17:30 and 18:30 hrs. The German General Schmidt considered this totally unnecessary and reported immediately that his troops controlled the northern part of the city, which was definitely not true at that time.

Meanwhile the news had arrived that the Germans had demanded the surrender of Utrecht under the threat of the destruction of the city. This was enough for Winkelman. Obviously the Germans were determined to destroy all the big cities in case he would continue fighting.

Aftermath

Up to the present day a debate is going on about the question whether the bombardment should be considered a tactical bombardment, a strategic bombardment or simply an act of terrorism. The target in itself, the inhabited centre, did not have any military significance. Rotterdam however was a defended city, in the middle of a frontline.

After the bombardment the city centre was in ruins, here the Hoogstraat Source: Public Domain (unknown)

In spite of the criticism, one may have on the view of Göring and Hitler regarding such bombings, the target was certainly strategic. After all, the intention was to force the Dutch into capitulation. However, by bombing the inhabited centre of Rotterdam, instead of the positions held by the Dutch, it could not be considered a tactical bombardment but took the character of terror bombing. In particular the subsequent threat to lay the entire city of Utrecht in ashes underlines this.

Since World war II, there have been many discussions in various articles about this issue. Often it has been said that it must be considered an "accident". The German planes were supposed to be sent back by firing red flares and owing to circumstances these flares were not noticed by a part of the planes.

Under international law, however, one thing is clear. Back in 1938 the 19th assembly of the League of Nations unanimously accepted principles that forbade the bombing of civilian targets, no matter the circumstances. Even on September 1st, this principle was endorsed by Hitler himself. The order, given to the crews of the bombers, was also clear, deliberately throwing bombs on civilian targets, without distinguishing between civilian and defended military targets. On this basis, one can certainly speak of terrorist bombing. It goes too far, however, to list this bombardment in the row of, for instance, London, Coventry and cities like Berlin, since the bombing of Rotterdam happened to a defended city. It was after all the Dutch supreme command that wished to defend Rotterdam to the utmost. Where international law is concerned, one can certainly speak of an act of terrorism, the debate on this issue however will always keep supporters and opponents.

Information

- Article by:

- Wilco Vermeer

- Translated by:

- Cor Korpel

- Published on:

- 01-09-2013

- Last edit on:

- 30-09-2024

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Sources

- AMERSFOORT, H. & KAMPHUIS, P., Mei 1940, 2005.

- ELFFERICH, L., Eindelijk de waarheid nabij, Leopold, Den Haag, 1983.

- KNEEPKENS, M., In het rijk van Demonen, Uitgeverij Ad, Donker, 1993.

- MIDDELKOOP, T. VAN, Een soldaat doet zijn plicht, Europese Bibliotheek, Zaltbommel, 2002.

- NOLYWAIKA, J., Die Sieger im Schatten ihrer Schuld, Deutsche Verlagsgesellschaft, 1994.

- STEENBEEK, W., Rotterdam, Standaard Uitgeverij, Antwerpen, 1974.

- Anneveldt S., original article at Go2War2, 2001

- Brongers E.H., Het bombardement van Rotterdam - mei 1940, Armamentaria nr. 24, 1989.

- Jacobsen H.A., Der Deutsche Luftangriff auf Rotterdam, Zeitschrift für die Europäischhe Zicherheit, jrg. VIII, nr.5, mei 1958.

- League of Nations, official Journal, supplement 182, octobre 1938.

- Opperbevelhebber van Land- en Zeemacht, Bericht van de capitulatie n.a.v. het bombardement op Rotterdam en de bedreiging van Utrecht, telegram Wo2, Sectie Militaire Geschiedenis, nr 503/11, 14 mei 1940