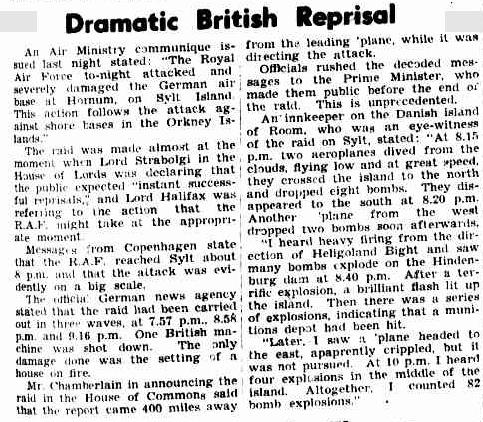

Bombardment of air base Hörnum, 19-20 March 1940

Preface

At the outbreak of World War Two RAF Bomber Command consisted of five Groups. The Command possessed four types of bombers with which every part of Germany could be reached, with the exception of the very east. Nevertheless, the role of Bomber Command during the first six months of the war was confined to reconnaissance-flights, attacking German shipping and nickelling (dropping propaganda leaflets). Not until March 1940 did Bomber Command launch an assault on a German land target. The Command bombed the air base at Hörnum, on the island of Sylt, during the night of 19/20 March 1940. It was a reprisal raid for the Luftwaffe bombardment on the naval base in Scapa Flow at the Orkney Islands and was ordered by the British government.

Western Air Plans and the attack on Scapa Flow

From 1934 Great Britain had undertaken a programme of re-arming as a consequence of growing tensions in Europe. Aerial warfare had become more and more important during the Interwar period. Bomber Command had outlined a detailed set of plans in 1936, in case of a German attack. These ‘Western Air Plans’ – sixteen in total – held different scenarios, like bombing raids on the United Kingdom or a land offensive against France, and Bomber Command’s targets were adjusted to them. However, help to Poland wasn’t part of the Western Air Plans, because it was out of the bombers reach. So when the German armies advanced eastwards, the role of Bomber Command was confined. This had to do with an appeal from the American President Roosevelt as well. He appealed to the countries at war not to carry out any bombing operations on undefended towns or other targets where civilians might be hit. Great-Britain and France gave Roosevelt assurances at once and Germany did so on 18 September. It proved difficult to define purely military targets, so the Air Ministry ordered no targets on German soil were to be bombed at all. The bombers could therefore only attack Kriegsmarine ships at sea or drop propaganda leaflets.

However, fourteen German bombers attacked the British Home Fleet at its base in Scapa Flow on Saturday 16 March 1940. The bombs inflicted damage on HMS Norfolk and killed four men. One bomber dropped its bomb load over the village of Bridge of Wraight which killed the 27-year old James Isbister and wounded seven more civilians.

Reprisal raid

In reply to the Luftwaffe bombardment the British government ordered Bomber Command to attack a German ground target. They chose the airbase of Hörnum, on the southernmost tip of the island of Sylt. The base was located near the German-Danish coast and the Luftwaffe used it to operate seaplanes. A force of fifty bombers had to cause as much damage as possible. The aircraft came from No.4 (thirty Whitleys) and No.5 (twenty Hampdens) Group. Seven Whitleys came from No.10 Squadron. They were led by their squadron commander, Wing Commander William Staton. He was an advocate of target marking and his suggestions would later lead to the formation of the Pathfinder Force. The crews of 10 Squadron were full of excitement at the briefing, now they were to carry out a real bombardment for the first time.

The bombardment took place during the night of 19/20 March 1940. The thirty Whitleys commenced the bombing and their attack lasted four hours. It was followed by a 2-hour bombardment by the twenty Hampdens. Visibility was good and on their return to base 41 crews claimed to have hit the target. Only one bomber, Whitley N1405 of No.51 Squadron, was lost. The aircraft was hit by flak and crashed into the sea to the north of the island. The crew of five was killed in the crash.

Three bulletins were issued by the Air Ministry during the attack. The first, in the evening of 19 March: "Tonight the Royal Air Force attacked and severely damaged the German air base at Hornum, on the Island of Sylt. This is one of the shore bases from which German aircraft operate against our naval forces and merchant shipping. This action follows the attack upon our shore bases in the Orkneys." The second was made public at 4 a.m. on the following morning: "The attack by aircraft of the Bomber Command upon the Hornum air base, on the Island of Sylt, which started at about 8 p.m. yesterday evening was still in progress at 3 a.m. this morning. The first aircraft to take part have already returned in safety and captains report accurate bombing of the objective. Some searchlight and anti-aircraft gun opposition was encountered." The last bulletin was issued at 7.45 a.m.: "The attacks made on Hornum last night were spread over a period of about seven hours. All our aircraft have returned safely with the exception of one which is overdue and must be presumed to have been lost. The information now available shows that the damage reported earlier is very extensive and includes direct hits on slipways and hangars."

No.10 Squadron and its commander became temporary heroes because of their involvement in the attack. The press had been informed about the reprisal raid to bring it to the attention of the British people. Most of the publicity descended on 10 Squadron. The Daily Mirror published a story on ‘Crack ‘Em Staton’ and his leadership in the attack on Sylt. The bombing of the base at Hörnum drew the attention of the foreign press as well. It was reported that severe damage had been inflicted on the base. The Australian newspaper ‘The Argus’ mentioned that dumps, hangars, slipways and barracks had been wrecked.

Aftermath

Two Bristol Blenheims of No.82 Squadron were sent to Sylt for photo reconnaissance on 21 March. These photos however showed only minor damage to the base and its installations. The staff at Bomber Command considered every possible explanation, including that the Germans had repaired the base overnight. Their commander, Air Chief Marshal Sir Edgar Ludlow-Hewitt, was reluctant to this view. He had already started a discussion about the deficiencies of Bomber Command and its crews, but would lose his job a month later because of doing so. The report on the raid concluded that crews had the utmost difficulty in identifying and bombing targets, even under the best conditions. The attack had revealed the shortcomings of Bomber Command. A communique released to the press stated that the reconnaissance photos were of too poor quality to assess the damage caused by the raid.

During the night of 19/20 March 1940, the Air Ministry and Bomber Command had abandoned their strategy not to bomb targets on German soil as ordered by the British government. However, no civilians had been killed in the attack. A couple of weeks later ground targets, mainly airfield, were bombed again when the Germans invaded Norway. At the time of the German offensive in Western Europe in May 1940, more and more raids were carried out against ground targets. Although efforts were still made not to bomb civilians, the allies would expand their bombing offensive step by step.

Definitielijst

- Bomber Command

- RAF unit which controlled strategic and sometimes tactical bombing (as in Normandy)

- flak

- Flieger-/Flugabwehrkanone. German anti-aircraft guns.

- Kriegsmarine

- Germa navy. Part of the Wehrmacht next to Heer and Luftwaffe.

- Luftwaffe

- German air force.

- Marshal

- Highest military rank, Army commander.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- Pathfinder Force

- Unit flying ahead of the bombers to locate and mark the target with flares to enable the following bombers to drop their bombs at the pre-set time, height and course from the target.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- RAF

- Royal Air Force. British air force

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

- Squadron

- A military unit in the Belgian navy usually six to eight small ships operating together under one command. The smallest military unit in the Dutch air force of about 350 men. In most countries is the designation of a military unit thesize of a company. It is either an independent unit, such as a battery, or part of a bigger Calvary unit. In the air force it is the designation of a unit of aircrafts.

- strategy

- Art of warfare, the way in which war should be conducted in general.

Images

Reconnaissancephoto of the air base. Source: Royal Air Force.

Reconnaissancephoto of the air base. Source: Royal Air Force.Information

- Article by:

- Pieter Schlebaum

- Published on:

- 01-05-2015

- Last edit on:

- 30-09-2024

- Feedback?

- Send it!