Operation Haudegen

Introduction

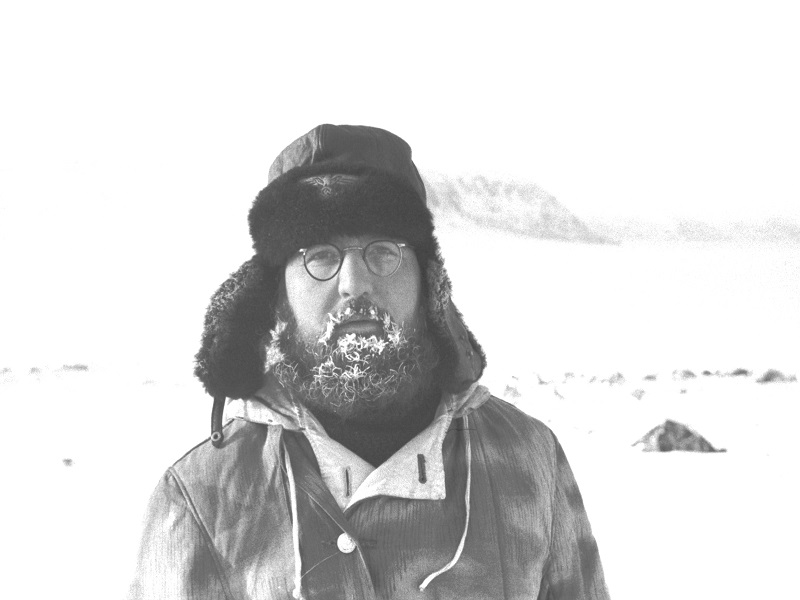

Operation Haudegen was the code name of a secret mission of the meteological department of the Kriegsmarine on the island of Spitsbergen, carried out by a small complement of 11 men. The name Haudegen (Swashbuckler) referred to the commander of the unit, Dr. Wilhelm Dege. It was the last unit of the Kriegsmarine to surrender as late as September 5th, 1945, forced by circumstances; nearly four months after German general Alfred Jodl had signed the unconditional capitulation of the German armed forces in Reims, France on May 7th, 1945.Wilhelm Dege

Dege qualified as a teacher in 1931 and started teaching at a primary school. At the same time he studied geography, geology and history. During 1935, 1936 and 1939 he made several expeditions to the island of Spitsbergen on his own initiative and made his doctorate in 1939 with a thesis on the northern part of the island.Wilhelm Dege was a geographer first and foremost (geology was his secondary subject). His task on Spitsbergen was therefore first of all of geographical nature. His knowledge of the island from his previous expeditions, as well as his knowledge of the language and his survival skills were of great value after the German invasion of Norway in May 1940.

The training

In the winter of 1943, on the snow covered Goldhöhe, the German name for a training camp on the hills of the Karkonosze (Giant Mountains), a mountain range on the border between Czechoslovakia and Poland, 60 volunteers were in training for a secret mission. They had to learn skiing, abseilen (descending down a cliff or building on a rope), how to build snow cabins, handle polar dogs and dog sledges, navigate their way across endless plains of snow and ice but were also taught how to cook and bake. Weathermen taught the men how to use meteorological instruments in order to determine the weather conditions. In 1944 they were taught their last skills, mountaineering, how to traverse mountainous terrain, battle positions and defense and the use of fire arms for their own safety in case an ice bear crossed their path. Meanwhile paramedics held crash courses in medicine like extracting teeth, attending to gunshot wounds but also how to amputate frozen limbs. The men heard all sorts of rumors and they did assume that in the future they were to be deployed in the Arctic region in order to provide weather reports for navy and air force.The start of Operation Haudegen

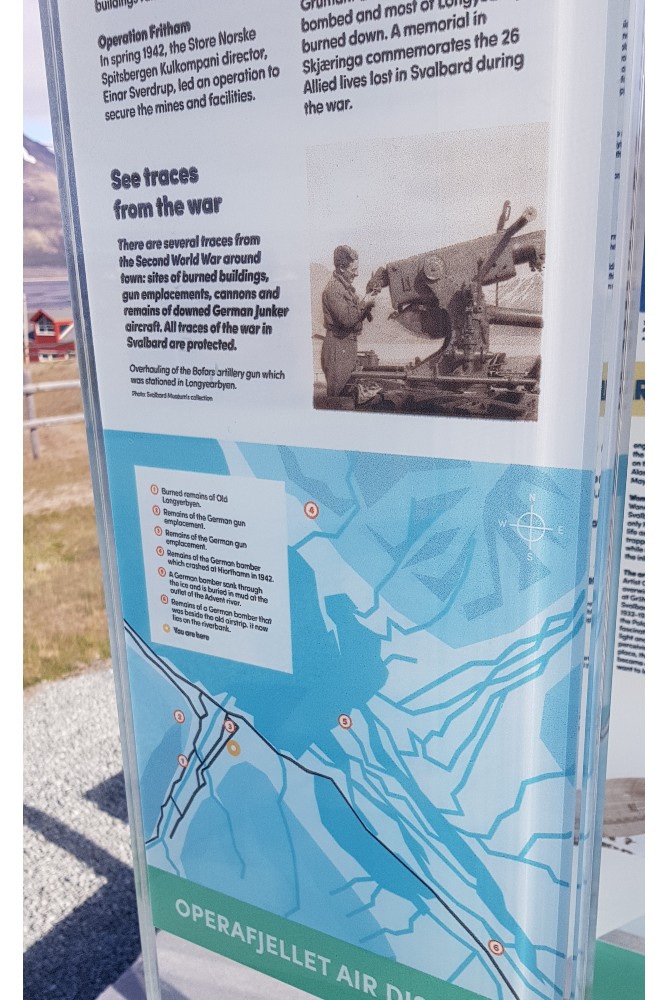

At the end of the training in 1944, 10 wireless operators were selected to begin their task. The small unit was taken by U-boat from the Norwegian port of Tromsø to their final destination on the east coast of Spitsbergen on the island of Northeastland (Nordaustlandet in Norwegian), deeply hidden in the Rijpfjord. While waiting for the vessel, commander Wilhelm Dege told his men they were tasked with setting up and operating a weather station. He explained further that the German army was under fire from all directions and that the army command wanted to have weather developments from the Arctic region in the direction of Europe at its disposal in order to enable navy and air force to prepare for bad weather. It has been proved time and again by the history of the various wars and the operations that have been carried out during these wars that it is expedient to know beforehand what the weather is going to be like.Spitsbergen (Svalbard in Norwegian) is an archipelago in the Northern Ice Sea, some 351 miles north of Norway, consisting of three large and some 80 smaller islands. The archipelago has a special status in the Kingdom of Norway since 1920. Dutch whale hunter Willlem Barentz christened the islands Spitsbergen when he discovered them in 1596. In 1925, Norway opted for the name Svalbard, derived from an Icelandic text of the 12th century which can be translated as cold rim or cold coast.

On arrival at Spitsbergen it was hard work to get all the equipment, arms, munitions, food, building materials and their meteorological instruments ashore quickly. U 307 and the supply vessel Karl J. Busch immediately returned to Norway. The polar winter set in and daylight became increasingly less. The risk of being discovered by Allied aircraft or war ships was great. Soon, two inconspicuous flat-roofed huts were constructed of wooden panels and camouflaged with white nets.

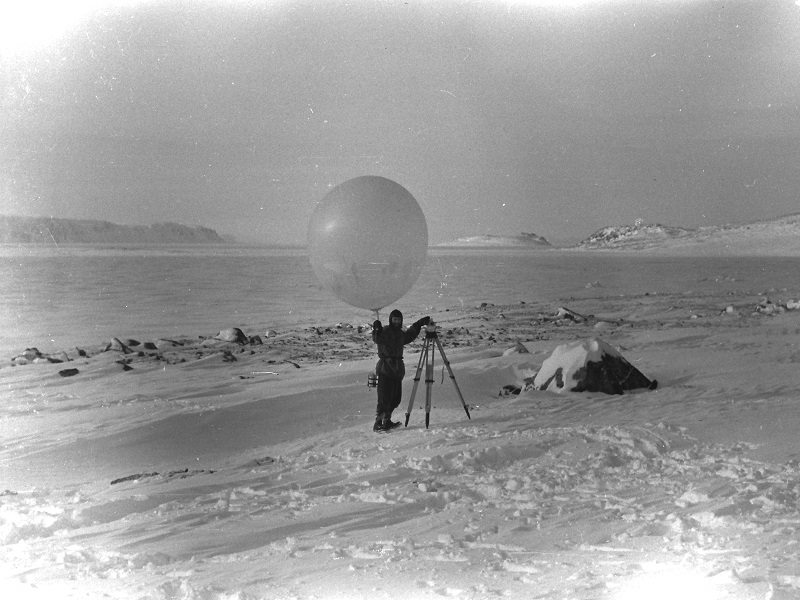

Operation Haudegen started in December 1944 as soon as the construction of the weather station was completed. Each day, five coded weather forecasts were transmitted to the weather station in the port of Tromsø. Commander Dege used the remaining time for scientific research in the arctic region.

The conditions on the North Pole were harsh for the unit. The men had a hard time getting used to the long polar night, 126 days without the sun rising. An encounter with an ice bear was dangerous, the reason why they always went out in pairs, armed with hunting rifles. In the arctic winter, temperatures well below freezing point and snow storms did not make the conditions any more bearable.

And yet: "It was a marvelous time," Siegfried Czapka, at the time 19 years old, told the German magazine Der Spiegel in 2010, "it was an unforgettable experience; we had everything but beer."

Efforts to pull the unit out

While the unit had little to fear from the war on the icy plains of Spitsbergen, on the European mainland the tide was turning for the German army which suffered heavy losses. In late April 1945, the Luftwaffe inquired about landing facilities near the weather station in order to pick up the group Haudegen. The men constructed an improvised landing strip in a short time and waited for a few days, "but no aero engines were heard; instead, we heard on radio Germany had capitulated."The forgotten unit

While German general Alfred Jodl (Bio Jodl) signed Germany’s unconditional surrender on May 7th, 1945 in Reims, France, the unit on the Norwegian island of Spitsbergen was completely forgotten by German military command.Desperation sets in

The members of the Group Haudegen were getting desperate, their task was finished and for them the war had ended as well. They finally wanted to go home to see how the home front was doing after the capitulation. The only way to achieve this was to contact the Allies by radio which would probably result in their being made prisoners of war. Dege remained optimistic. "The crew of a weather station can hardly be considered war criminals," he said.Radio contact with the station in Tromsø, now manned again by Norwegians, proceeded arduously. They frequently sent their coordinates on the wave lengths in use by the Allies but no ships or aircraft appeared. To kill time, Wilhelm Dege was more or less forced to continue his geographic research on Spitsbergen while at the weather station, the crew kept busy with table tennis until the last ball had succumbed. Towards the end of August, a message from Norway was finally received to the effect that in early September a vessel was to sail for Spitsbergen.

Their relief was great when in the night of September 3rd to 4th, a vessel, the Blaasel, berthed in the fjord near the weather station. Actually she was used for hunting seals but she had been chartered by the Norwegian navy in order to pick up the Germans. Commander Dege insisted on formally surrendering to the Norwegian skipper Albertsen who did not know how to handle this. Dege handed his gun to the captain, saying: "I don’t know how to handle this either." That belatedly ended the capitulation, almost four months after Jodl had put his signature on paper.

Prisoners of war

On arrival in Tromsø harbor, the unit was taken prisoner immediately. In December 1945, after three months in captivity, Wilhelm Dege returned home which now was in West Germany following the new definition of the borders. After the war he was temporarily employed in his former profession of teacher until he became lector in geography at a school for teachers. He retired in 1976 and passed away three years later.The men of the unit tried to meet each other for a yearly reunion but during the Cold War, this was difficult if not impossible due to the tensions between East and West Germany. The men of Haudegen, living in West Germany were duly invited by their former colleagues in East Germany but none of them dared travel to East Germany. This only changed after the collapse of the Berlin Wall whereupon the men could again meet in freedom.

Siegfried Czapka, the youngest member of the unit, passed away on August 12th, 2015 at the age of 90. Nowadays, the former weather station on Spitsbergen is part of Norway’s historical heritage.

Definitielijst

- capitulation

- Agreement between fighting parties concerning the surrender of a country or an army.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Kriegsmarine

- Germa navy. Part of the Wehrmacht next to Heer and Luftwaffe.

- Luftwaffe

- German air force.

- U-boat

- The German name for a submarine. German U-Boats (Submarines) played a very important role during the course of warfare until May 1943. Many cargo and passenger ships were torpedoed and sunk by these assassins of the sea.

Images

Information

- Translated by:

- Arnold Palthe

- Published on:

- 19-12-2016

- Last edit on:

- 30-09-2024

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Sources

With thanks to Dr. Eckart Dege for his permission to use the photos. We would like to mention his father’s book 'Gefangen im arktischen Eis. Wettertrupp Haudegen - die letzte deutsche Arktisstation des Zweiten Weltkrieges', published by Convent in Hamburg, 2006. The book is also translated in English, entitled: "War North of 800".

-De vergeten Wehrmacht-eenheid van Spitsbergen, Nos.nl

-Kriegsende in der Arktis, Spiegel Online

-Wilhelm Dege, de.wikipedia.org

-Reuzengebergte, nl.wikipedia

-Geheime deutsche Wetterstation in der Arktis 1941 - 1945 , Lexikon der Wehrmacht

-D-Day: De belangrijkste weersverwachting uit de geschiedenis, IsGeschiedenis.nl

-Nordauslandet, nl.wikipedia

-Spitsbergen, wikipedia.nl

-Het weer als cruciale factor in oorlogstijd, Weeronline.nl

-Post War U-boat events, Uboat.net

-Spitsbergen-Svalbard.com

-Vergessene Helden, Polarnews.ch