Pre war years

Introduction

It was a historical first: war correspondents of a Propaganda-kompanie (PK or propaganda company) of the Wehrmacht fighting alongside front troops. "Whilst the pioneer of the shock forces cold-bloodedly aims his flamethrower without fear of death in order to break open an enemy bunker, " so Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels (Bio Goebbels) declared in May 1941, "a PK Mann will stand beside him with equal contempt of death and cold-bloodedness to record this dramatic and spectacular event in words or images." One of these PK men, called Kriegsberichter (war reporter) was the German author and journalist Thaddäus Troll, whose real name was Hans Bayer.

Youth and study

"Soap factory Bayer," it said for decades on the front of the building – meanwhile torn down – on Marktstrasse 11 in a suburb of Stuttgart, Bad Cannstatt. The Bayer family lived on the first floor and the working space and the shop where soap was produced and sold, were sited on ground level. Whoever visited the shop in the 20s of the previous century would probably have been served by a youngster called Hans, eldest son of owner Paul Bayer and his wife Elsa. Together with his junior brother Erich, Hans often helped out his father in the family business after school. It was to be expected that Hans, born in 1914, would succeed his father but at a young age he already had other interests. He loved the theatre and often went to shows in the Stuttgart theatre with his mother. Writing however was his biggest passion and he dreamt of a career in journalism.

After having graduated from the Johannes Kepler Gymnasium in Cannstatt, his father managed to get his son a traineeship during the summer of 1932 on the editorial staff of the Cannstatter Zeitung. Subsequently, Hans studied German language, literature, history of art, theatre science and journalism in Tübingen, Munich, Halle and Leipzig from 1932 to 1938. During the holidays, he made contributions to the Ludwigsburger Zeitung including articles on politics and reviews of theatre, movies and concerts.

During his time as a student, the seizure of power in Germany by the Nazi Party (N.S.D.A.P. or National socialist German Workers Party) of Adolf Hitler (Bio Hitler) caused a political earthquake which did not go unnoticed by student Bayer. In 1933, the year Hitler was named Reichskanzler, he joined the Sturmabteilung (SA), the paramilitary movement of the Nazi Party. Probably his membership was meant only not to be put in a disadvantageous position in a society that was soon dominated by the Nazis. He was not very active as a "brownshirt" and he left the SA in June 1937.

Since the start of his studies however, Bayer was an enthusiastic member of the Turnerschaft Palatia, a German-nationalist student corps in Tübingen where students traditionally crossed swords in fencing duels. Student life with the inherent duels, discussions and drinking orgies also appealed very much to Bayer. When in 1935, in a drunken mood, he damaged a wall portrait of Hitler, it spelled a sudden end to his membership of the corps because it was feared the student organization would be disbanded if this incident was ignored. It did not influence the course of his studies in any way though and in June 1938, Bayer passed his doctoral exam with a thesis entitled: "The press and messages of prisoners-of-war during the World War." From now on, he was allowed to call himself Dr. Phil. a title which not only included the subject of philosophy but for example sociology, political science and history as well.

Definitielijst

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- Sturmabteilung

- Storm detachment. Semi-military section of the NSDAP. Founded in 1922 to secure meetings and leaders of the NSDAP. Their increasing power was stopped during “The night of the long knives”, 29 and 30 June 1934.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Images

In the Propaganda companies

War messenger

In the year of Bayer’s graduation, dark clouds were gathering over Europe. German troops had invaded both Austria and the Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia in 1938, followed by the annexation of the rest of Czechia the next year. With that Hitler’s hunger for territorial expansion was far from appeased and German men were called up in their masses to serve in the Wehrmacht. Bayer was called up a few months after his graduation. He completed basic training in Nachrichtentruppe 25 in Cannstatt and just before the invasion of Poland, he was transferred to Nachrichten-Abteilung 178. Being a member of this unit, Bayer was involved in installing telephone communications on the German-French border. Following the capitulation of France on June 22, 1940, he and his unit were part of the army of occupation in France.

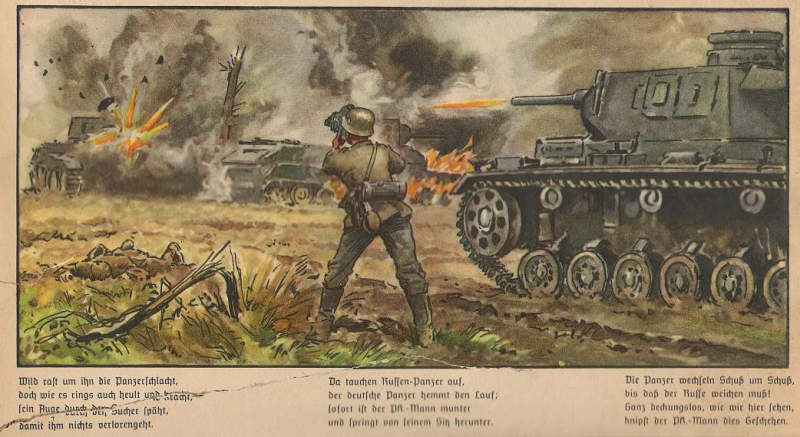

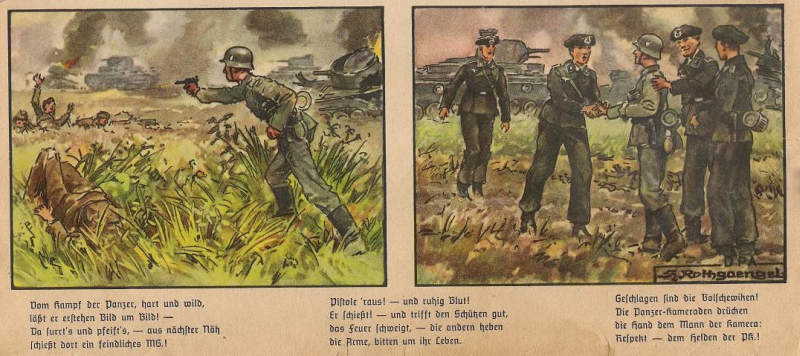

Serving as a private until the end of the war was certainly not Bayer’s cup of tea. As early as 1939 he had applied for the Propagandakompanien (PK) of the Wehrmacht. These companies were first deployed in 1938 in the invasion of the Sudetenland and were mainly tasked with reporting about the German actions in the war. At the invasion of Poland, the German army had 13 of these units: seven as part of the Army, six of the Luftwaffe and two of the Kriegsmarine. From 1940 onwards, the Waffen-SS had a Propagandakompanie at its disposal as well. The members of these units, Kriegsberichter (war messengers) occupied themselves with reporting about the war through newspaper articles, radio transmissions, photo’s, movies and drawings. Their work was distributed among the front troops and also on the home front after it had been subjected to military censorship by the high command and political censorship by the Propaganda department of Joseph Goebbels. The units may well have been under military command but individual correspondents were recommended and given specific tasks by Goebbels and his associates.

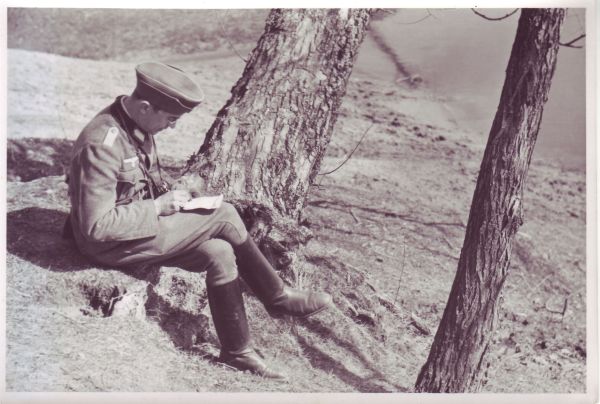

Initially, Bayer’s application was rejected but in October 1940, he was eventually transferred to the PK. He started his training at the Propaganda-Ersatz-Abteilung in Potsdam on October 11, 1940. While war correspondents today only operate integrated in military units, yet are no part of them, Kriegsberichter on the other hand were armed soldiers as well and so part of the army. "The PK Mann is not a reporter in the usual sense of the word but a soldier," so Goebbels said. "In addition to pistols and hand grenades he carries other weapons as well: the movie camera, the photo camera, his drawing pencil or his note book." Part of the course was therefore military training as well as lessons on the tasks of the PKs and the influence of propaganda. "Propaganda pulls a cord and you get what you want, contempt or hatred, boundless enthusiasm or indignation," as Bayer wrote in a letter to his girlfriend during his training.

The Warsaw ghetto

The real work for Hans Bayer as Kriegsberichter began on January 19, 1941 when he joined PK 689 which was stationed in Warsaw since the end of 1940 after first having taken part in the invasion of Poland and subsequently having been active in France in 1940. In the Polish capital, PK 689 was mainly involved in organizing theatre and cinema shows and meetings for German soldiers. In addition, publications including anti-Semitic ones in Polish were distributed among the local population and the paper Der Stosstrup (Shock troop) was published which was distributed among soldiers free of charge. Bayer’s first task for the company was peeling potatoes; it goes without saying he wasn’t too happy with this as a future war correspondent. He soon made his debut as a reporter however with an article in Der Stosstrup of February 5, 1941 on the inconveniences of wearing army boots. Later articles by him about the superiority of German civilization as compared to the Polish, were a better match with Nazi ideology.

Bayer’s unit was stationed in the Wola district which contained a section of the Jewish ghetto established in 1940. At the time the ghetto was sealed off from the rest of the city, some 380,000 Jews were living here, a number that would grow to 445,000 in May 1941. Due to an extremely high population density and severely limited food rations, living conditions were appalling and the death rate was high. In April 1941, PK 689 was ordered to report about this dismal place. Bayer’s colleagues took pictures and films. He visited the ghetto himself seven times between April 25 and May 8; on May 1, he was accompanied by Benyamin Zabludovsky, a member of the Jewish Council who showed him around. Bayer wrote three articles about the ghetto and all were published in May. One of the articles he made a contribution to, was a photographic report "Juden unter sich" (Jews among themselves) an article filled with anti-Semitic prejudices such as the charge that Jews spread diseases. Whether these texts actually came from Bayer’s pen is unclear, his name was not mentioned in the article and possibly, the text had been massively edited by the censors of the Propaganda department.

Definitielijst

- Abteilung

- Usually part of a Regiment and consisting of several companies. The smallest unit that could operate independently and maintain itself. In theory an Abteilung comprised 500-1,000 men.

- capitulation

- Agreement between fighting parties concerning the surrender of a country or an army.

- ghetto

- Part of a town separated from the outside world to segregate Jewish population. The establishment of ghettos was intended to exclude the Jews from daily life and from the rest of the people. From these ghettos it was also easier to deport the Jews to the concentration and extermination camps. Also known as “Judenviertel” or Jewish quarter.

- ideology

- A collection of principles and ideas of a certain system.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Kriegsmarine

- Germa navy. Part of the Wehrmacht next to Heer and Luftwaffe.

- Luftwaffe

- German air force.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- Waffen-SS

- Name of Military section of the SS.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Images

A radio reporter reporting from the front, December 1940. Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-L15659 / CC-BY-SA 3.0.

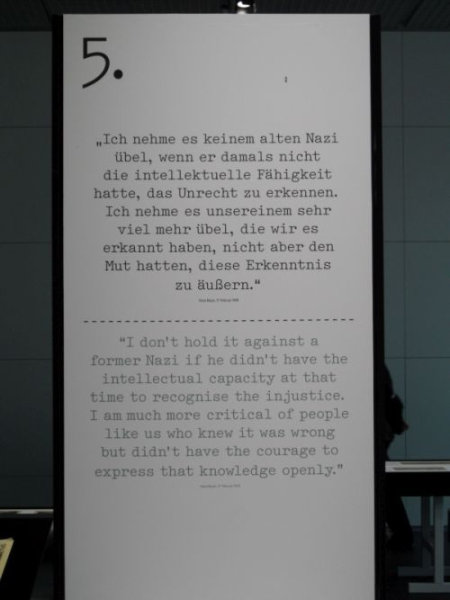

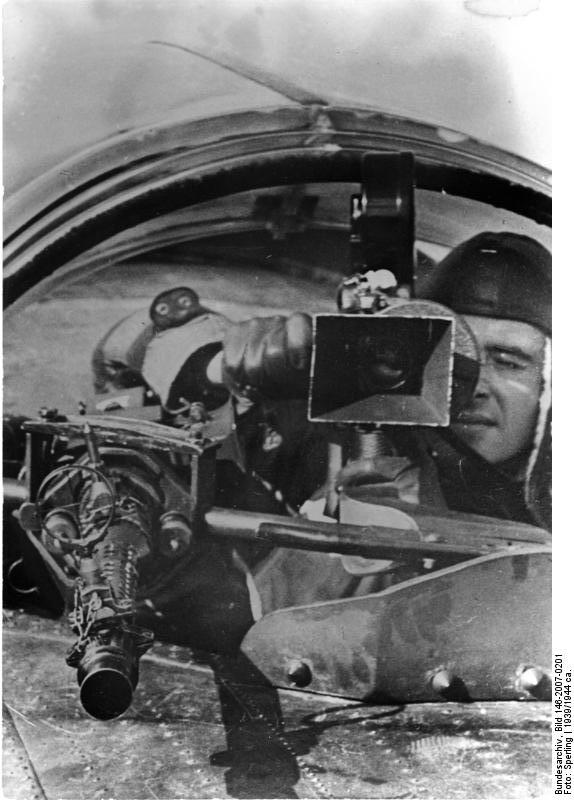

A radio reporter reporting from the front, December 1940. Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-L15659 / CC-BY-SA 3.0. A camera man of a Propagandakompanie filming aboard a Luftwaffe aircraft. Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-2007-0201 / Sperling / CC-BY-SA 3.0.

A camera man of a Propagandakompanie filming aboard a Luftwaffe aircraft. Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-2007-0201 / Sperling / CC-BY-SA 3.0.On the Eastern front

Invasion of the Soviet Union

From the moment German troops marched into the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, the importance of the Propaganda-kompanien only increased. The Nazis portrayed the war as an inevitable life and death struggle against the ultimate enemy, Bolshevism. Reports about German racial superiority, the successes of the Wehrmacht and the heroic actions of individuals at the front were meant to convince German soldiers and civilians alike of the importance of the struggle and of a German victory. Towards 1942, the number of Kriegsberichter had grown to some 15,000 men, spread over 30 Propaganda-kompanien. Until 1945, they produced a total of 80,000 pages of reports, 3,107 miles of film and 3 million pictures.

The day prior to the German attack on the Soviet Union, Bayer’s PK 689 was posted to 4. Armee commanded by Generalfeldmarschall Günther von Kluge (Bio Von Kluge) which took part in the advance on Moscow as part of Heeresgruppe Mitte. Bayer and his colleagues of the first platoon reported on numerous battles including Brest-Litovsk, Bialystok, Minsk, Gomel, Mogilev, Smolensk and Bryansk. Bayer wrote about the speedy advance of the German army which ground to a halt in December 1941 at some 37 miles from the Russian capital, due to the autumn rains and the poor preparation for the early onset of the Russian winter. From that moment on, Bayer focused on the daily life of the soldier, the life of the local population under German occupation and heroic achievements of individual soldiers and divisions in his articles. He kept silent about the crimes against prisoners-of-war, Jews and alleged partisans committed on the Eastern front. His work was published in the army paper Der Stosstrup and in various other papers in the Reich.

Bayer scored his greatest success as Kriegsberichter with his article "Urlaub auf Probe" (Holiday on probation). The satirical article was about the fictional person Alois Hinterhuben, a battle-hardened German front soldier who is an annoyance to his fellow men during his leave due to his rough manners. Initially, Bayer wrote the article on occasion of New Year 1941-1942 but his superiors did not give permission to publish. It was already circulating among soldiers though and in February 1942 it was first published anonymously in the front paper "Das Neueste." Later on it was published in other papers as well, including "Der Stosstrup" and other papers in the Reich. Bayer’s humorous view on a widely known subject as brutalization of men on the Eastern front appealed to the readers. Meanwhile recognized as the author of the text, it was his breakthrough to a larger audience.

Hardening at the front

The rank of Sonderführer and an armband with the text: "Kriegsberichter" made them stand out from other soldiers but at the front, they were not spared the violence of war either. "The new German war correspondent is not a guest but a comrade, fighting alongside the troops," those were the words of Generalmajor Hasso von Wedel, head of the propaganda department of the Wehrmacht on the O.K.W. in Berlin. That applied equally to Bayer as he and his unit did make their military contribution. For his participation in the fighting near Gomel and in the vicinity of Mogilev he was awarded the Eisernes Kreuz ii. Klasse (Iron Cross 2nd class) in August 1941. A few days after the invasion of the Soviet Union, on June 25, 1941 his company was involved in the clearing of a forest near Ruzhany in Byelorussia were various Red Army soldiers were taken prisoner. Three of them were injured and executed by order of the commander of PK 689 although evacuation of the wounded men on make-shift stretchers made of branches had already begun.

Although Bayer did not mention the event mentioned above in his diary, from other notes it appears unmistakably that he did not close his eyes to the cruelty of war. "War is a terrible inferno and it is difficult to be fully involved without getting your hands dirty," as he noted in 1941. In July 1941, he described his amazement about "how cold-blooded and harsh you can act when it is absolutely necessary." Despite his wish the war would be over soon, "for the sake of humanity," he did confess in August 1941 that exposure to danger was appealing to him as well. "Taking part in an attack, a reconnaissance mission or rowing in a rubber dinghy is an exciting experience." He was fully aware of the risks though because on the same day three prisoners-of-war were executed by his company, a colleague in his platoon, camera operator Rolf Carl was killed. He was one of the 546 members of the PK who lost their lives up to October 1943. Bayer himself narrowly escaped execution in October 1941 after having been a prisoner-of-war of the Soviets for 32 hours. Together with two others, he managed to escape and return to his unit.

In the first six months of the war in the Soviet Union, Bayer was shocked by the poverty and the misery of the local people which he attributed to Bolshevism. In an article of June 27, 1941 he described how ethnic Germans and Ruthenians (a name for the population of roughly the Ukraine and Byelorussia) had been suppressed for years by "Bolshevists and political commissars" whom he considered Jews without exception. He emphasized the happiness of the population on arrival of the Wehrmacht which was considered as its liberator. Bayer and his colleagues also suffered appalling conditions in the fall of 1941. They suffered from the bad provisioning, the continuous pouring rain and the cold of winter. An article by Bayer of September 4, 1941, in which he praised the provisioning of the army by the field kitchens and the companies of bakers and butchers was meant to kill rumors on the home front about the bad supply of food stuffs to the front but German soldiers were actually starving.

Definitielijst

- Eisernes Kreuz

- Iron Cross. German military decoration.

- Heeresgruppe

- The largest German ground formation and was directly subordinate to the OKH. Mainly consisting of a number of “Armeen” with few directly subordinate other units. A Heeresgruppe operated in a large area and could number several 100,000 men.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Iron Cross

- English translation of the German decoration Eisernes Kreuz.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Images

Detail of a front page of the army paper Der Stosstrupp, in which various articles by Bayer were gepublished. Source: DHM.

Detail of a front page of the army paper Der Stosstrupp, in which various articles by Bayer were gepublished. Source: DHM.The tide turns at the front

The German advance grounds to a halt

After the advance of the German army had ground to a halt before Moscow, Bayer called on his readers in an article of January 6, 1942 in the Stuttgarter Neues Tageblatt to keep in touch with the soldiers at the front by sending them letters. The same months he returned to Germany temporarily for a series of speeches to local party offices and military schools, organized by the Department of Propaganda. On January 22, 1942, he delivered a speech about the military campaign in the Soviet Union to the workers in an armaments factory in Teltow near Berlin. On May 24, 1942, he published an article on this visit, emphasizing again the communication between the front and the home front. He failed to mention the slave laborers employed in the factory though.

After having been named "one of the best writing journalists" by the Department of Propaganda, Bayer finished a course for war correspondents in April 1942, again as one of the best. In May he returned to his company on the Eastern front where he was placed in command of a battalion. On July 20 he was awarded the Ostmedaille, a decoration for civilians and military personnel who had served on the Eastern front from November 15, 1941 until April 15, 1942. His stay at the front was short lived though as in August 1943 he contracted jaundice and was transferred to the military hospital Bühlerhöhe in the Black Forest. After his recuperation he took a course at the Kriegsschule in Potsdam. In the summer of 1943, he was promoted to Leutnant and transferred to PK 670 in Kiev in the Ukraine to reinforce the editorial staff of the army paper Der Sieg (Victory).

Bayer stayed in Kiev only for a short while for after just a month, the editorial staff and the production of the paper were transferred to Warsaw due to the advance of the Red Army which would recapture Kiev in November 1943. Bayer was happy to be back in Warsaw. His attended theatre shows and concerts and met old acquaintances. On the editorial staff of Der Sieg he deputized for the editor in chief in his absence. In his articles, he concentrated on serial and humorous stories, portraits of the city and articles on German poets and thinkers. He left political articles to his colleagues although he did call, in his first article as deputy editor in chief, on soldiers to hold their ground. To Bayer’s great joy, he was promoted to editor in chief in August 1944. The editorial columns he wrote were more in line with Nazi ideology. He called on soldiers to do their utmost to protect their homeland and he praised the abolition of working hours in the war industry, something he wanted to introduce at the front as well.

Hunted down like rabbits

A few days prior to the Polish uprising in Warsaw on August 1, 1944, Bayer and his editors moved east to Lodz or Litzmannstadt as the Germans called it. When it became too dangerous in December 1944, due to the advancing Soviet armies, the editors of Der Sieg continued their work aboard a so-called printing train equipped with everything necessary to publish a paper. Aboard the train, they had to make do though. "In this cramped space and under continuous observation, it felt like being in prison," he wrote on January 1, 1945. They traveled to the north, their first destination being Soldau (Dzia-dowo) in present northern Poland. Next, the train took a whimsical route through east and west Prussia which took Bayer and his colleagues in a roundabout way to Bütow(Bytów) and Neustadt (Wejherowo) to the Neufahrwasser district (Nowy Port) in the port of Danzig (Gdañsk) the journey’s final destination.

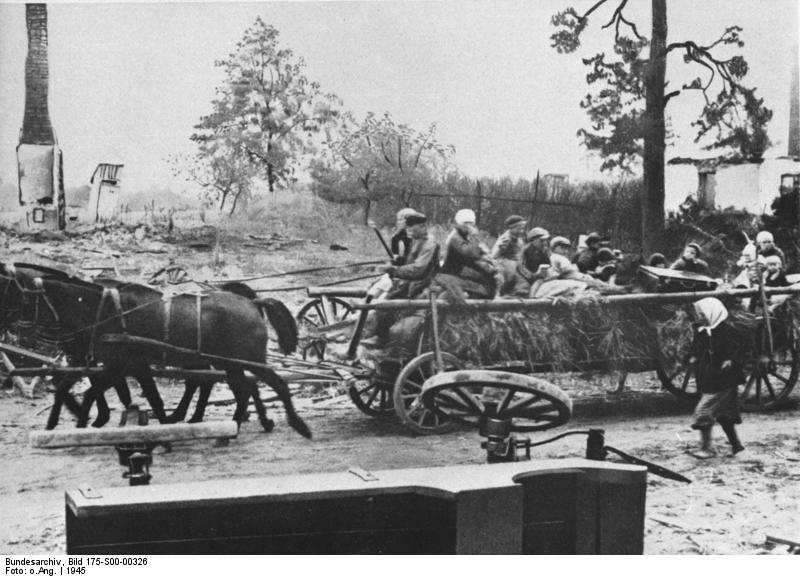

During the train ride of some 311 miles, Bayer witnessed long, hapless columns of civilians fleeing before the Red Army making their way in the freezing cold. "Now our own compatriots are walking past as if in a large funeral procession," he wrote in his diary on January 16, 1945. "Nothing has been prepared for them. It was considered defeatism if one prepared for the worst. It has happened nonetheless. The Eastern front has collapsed in a way even worse than the most pessimistic souls could ever have imagined. We were hunted down like rabbits." On January 24, Bayer witnessed a horrendous scene on a bridge across the Weichsel. A woman was standing on the bridge, irresolutely as if considering suicide. Two packages she held in her arms contained the frozen bodies of her twins she could not bury in the frozen ground. As she hesitated whether to throw the bodies into the flowing water, a man took the packages from her and cautiously dropped them into the river. "We all go our separate ways as if we have seen hell," Bayer noted in his diary afterwards.

As early as the previous year, high command had been complaining about the tone of Der Sieg becoming too a-political. "The gentlemen now want a Stürmer tone but with that I cannot be of any service to them," he concluded in March 1945, referring to the sickly anti-Semitic weekly of Nazi official Julius Streicher. The same month, the last edition of Der Sieg was published; on March 25, 1945 Bayer and his colleagues celebrated its burial ceremony which was also their last meeting. After having occupied himself with military training of members of the Volkssturm, the people’s militia established in 1944, in Soldau in January; in the last weeks of the war, Bayer was in command of two transit camps for German refugees in the vicinity of Danzig. He provided them with food, housing and transport across the Baltic Sea. On May 8, 1945, he boarded the last vessel to Germany and was subsequently taken prisoner-of-war in Neustadt in Schleswig-Holstein by the British.

Definitielijst

- ideology

- A collection of principles and ideas of a certain system.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

Images

Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels meets the commanders of the Propaganda-kompanien in Berlin, January 28, 1941. Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-B00548 / CC-BY-SA 3.0.

Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels meets the commanders of the Propaganda-kompanien in Berlin, January 28, 1941. Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-B00548 / CC-BY-SA 3.0.After the war

Prominent journalist

Bayer was imprisoned by the British in Schleswig-Holstein in PoW camp Putlos were he became director of the camp theatre at the end of May. He was released in July 1945 and returned to Bad Cannstatt. There he completed his deNazification form and asked the American authorities permission to continue his work as a journalist. He wrote on his form he had never written any political articles during the war, "just reports on the fighting, descriptions of land and people, psychological articles and about cultural subjects." Early 1946 he received his work permit and was acquitted by the deNazification tribunal. The next year, the Stuttgart District Attorney (Staatsanwalt) belatedly opened an investigation into Bayer on grounds of "falsified information on the registry form." On this form, he allegedly omitted his N.S.D.A.P. membership. Bayer however denied having been a member of the Nazi Party and in 1948, the case was closed for lack of evidence.

After the war, Bayer continued his journalistic career. He was one of the founders of the political-satirical journal "Das Wespennest"(Wasps nest) that appeared until 1949. He distanced himself immediately from National socialism; with his contribution he wanted to "liberate his fellow men from the last remnants of the mental tyranny of National socialism and to erase its ideology from the minds." Initially he used Peter Puck as nickname but from 1946 onwards, his readers knew him as Thaddäus Troll. As he said himself, he had chosen this name in order to have his works stand on the left of the books by German author Tucholsky on book shelves. Because he still wrote theatre reviews in his own name, he later called his attitude "schizophrenic." He also published articles under his "new" nickname that had been published under his real name during the war. All told, he wrote over 70 books, hundreds of poems, theatre reviews and serials.

Bayer evolved into a prominent journalist in Western Germany as contributor to various renowned newspaper such as Der Frankfurter Allgemeine, Die Zeit and Der Spiegel. In 1962 he was awarded the Theodor Wolff prize, a yearly prize for journalists of German newspapers, named after a German-Jewish journalist who had been driven out by the Nazis in 1933. His greatest national success was his book "Deutschland deine Schwaben", published in 1967 in which he painted a picture in his habitual ironic tone of character and culture of the Schwaben, the population of southern Germany. In addition to being an author, Bayer also was one of the co-founders of the "Süddeutsche Schriftstellerverband" (Union of South-German authors) and an active defender of copyrights within the federation of German writers. He also was a member of the international writers union P.E.N. He actively resisted (inter)national political developments he considered totalitarian and he advocated freedom of the press and freedom of expression.

An undigested past

In post war Western Germany, it was no obstacle having been a Kriegsberichter because many former members of the Propaganda-kompanien managed to build a career unobstructed. Some former Kriegsberichter were Lothar-Günther Buchheim (author of "Das Boot", made into a movie in 1981), manager of the ZDF (German TV station), Karl Holzamer and Herbert Reinecker (script writer of, among other things, 281 installments of the police serial Derrick). Bayer kept this past a secret for many year, he called himself just a soldier of World War Two. As late as the 70s, this changed as his daughter discovered copies of Der Sieg in his bookcase and had asked her father about it.

After having supported the election campaign of Willy Brandt in 1969, Bayer was deeply impressed when Brandt, meanwhile federal chancellor, as representative of his generation, knelt before the monument commemorating the Warsaw uprising during his visit to Poland on December 7, 1970.

The years of silence and the shame about his involvement in the Nazi regime put heavy pressure on Bayer. "I don’t hold it against a former Nazi if he didn’t have the intellectual capacity at that time to recognize the injustice," he declared in 1978. "I am much more critical of people like us who knew it was wrong but didn’t have the courage to express it openly." Disturbed by depressions, Hans Bayer committed suicide at the age of 66 in his apartment in Stuttgart on July 5, 1980. He was buried in the Steigfriedhof in Stuttgart under the name he was best known by: Thaddäus Troll. A sculpture of the main character in Bayer’s play "Der Entaklemmer" (1976) in the Thaddäus Troll Platz in Stuttgart in Bad Canstatt, near the house he was born in, stands in memory of the adorable Schwabian writer whose undigested past led to his death. In the fall of 2014, in the documentation center Topographie des Terrors in Berlin, an exposition was dedicated to him.

See also: Final statement Streicher, Verdict Streicher

Definitielijst

- deNazification

- Post war policy of the allies in Germany to punish Nazi war criminals and to remove known Nazis from positions of power or public service.

- ideology

- A collection of principles and ideas of a certain system.

- National socialism

- A political ideology drawn up by Hitler based on the superiority of the German race, the leader principle and fierce nationalism that was fed by the hard Peace of Versailles. National socialism was anti-democratic and racist. The doctrine was elaborated in Mein Kampf and organised in the NSDAP. From 1933 to 1945 National socialism was the basis of totalitarian Germany.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- PoW

- Prisoner of War.

- Propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- socialism

- Political ideology aiming at slight or no class differences. Means of production are owned by the state. Evolved as a response to capitalism. Karl Marx tried to substantiate socialism scientific.

Images

Information

- Article by:

- Kevin Prenger

- Translated by:

- Arnold Palthe

- Published on:

- 19-01-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!