Crash of Lancaster ED928 at Utrecht

On the night of 22 -23 June 1943, a British bomber was shot down by a German night fighter. The four-engine aircraft was on its way to Germany, but never made it there. Instead, the plane exploded. Burning fragments of the plane fell down in the Wittevrouwen district of Utrecht. There were several victims, including five civilians and five crew members.

Lancaster ED928 and its crew

The tragedy began the day before, on the evening of the 22nd of June, when the four-engine AVRO Lancaster Mk III ED928 took off from Bourn airbase, in the county of Cambridgeshire. The target that night was Mülheim in North Rhine Westphalia in Germany. Bomber ED928 was to offer support during the attack. Between attack waves the bomber was to mark the targets again. The aircraft belonged to the No. 97 Squadron 'Straits Settlements', and was registered under the number ED928. On both sides of the aircraft the marking "OF-B" was applied, respectively the squadron code and the call sign: "B". The plane was still relatively new with only 54 operational flying hours.

There were seven crew members aboard the Lancaster. George Armstrong was the 29 year old pilot and captain. He made all the decisions during the flight. Edward Bellis, as flight engineer, was tasked with monitoring the technical status of the aircraft. He also assisted with the takeoff and landing by operating the speed control levers and synchronizing the engines, while the pilot literally had his hands full with the controls of the aircraft. From his position on the jump seat, Bellis could see Bapiste Sylviel Paul Davis, 'Paul', the 22 year old bomb aimer who was lying down in the nose of the plane. David, in turn, lying on his belly, looked out from his dome at the world that was raging beneath him. He was responsible for making sure that the bombs would be dropped accurately onto their targets and would take over control of the plane from the pilot during the target approach. In addition, he could operate the nose turret during the outward and return flight. John Mansfield, the navigator, was sitting behind the pilot. He had to make sure that the Lancaster would find its target in a darkened Europe in the middle of a hostile airspace and then return to its base in England.

David Williams was the wireless operator and with his 34 years he was the oldest crew member. He ensured that, while flying, all radio signals between the air base and the plane were received and sent. He was also able to listen to German radio messages in the hope of finding out about surrounding dangers as quickly as possible. Because he was still trained according to the old methods, he could also be deployed as a gunner. In addition, the aircraft should have the ability of defending itself while the others were performing their duties. Sydney Blackhurst took care of that. He was 22 years old and sat in the mid-upper turret, just behind the wings. He had a magnificent view in every direction from his spherical, plexiglas covered turret. In the dark night he regularly turned the turret around in order to discover any attackers who might try to surprise them in the darkness. Finally, in the tail turret, there was Alexander Laing, 22 years old and from Manchester. The only way that Laing could communicate with the rest of the crew was through the intercom and it was not uncommon for him not to see anyone during the flight. Moreover, the tail turret was not heated, so the flight was not only lonely for him but also particularly unpleasant because of the cold and draft. The hours-long flights could be especially unpleasant. None of them, except for captain Armstrong, wore their parachute during the flight, in order to be able to move freely.

Most of the crew was British, except for David and Armstrong who were with the Royal Canadian Airforce (RCAF). The men had carried out eight missions together. The first was on 28-29 March 1943 to the French city of Saint Nazaire, where the famous German U-boat port was located. Following that, there was a mission on 2-3 April, during which they dropped sea mines on location. On 13-14 April an attack was carried out on the city of Spezia in Italy where a large Italian port was located. Following that was a bombing of Essen on 30 April – 1 May and on 4-5 May a bombing of Dortmund. On 12-13 May they participated in an attack on Duisburg and on the 28-29 May a bombing of Wuppertal. This was followed by a period of inactivity, they carried out their next mission a few weeks later on the 16-17 of June. The target was Cologne. On the 21-22 of June a bombardment was carried out on Krefeld.

The night of 22 -23 June 1943

After the bombing of Krefeld, a few hours of rest followed, because later that same night (22 June) they would take off again, with the city of Mülheim in Germany as their target. In total, 557 twin and four-engine bombers were deployed for this attack: 242 Lancasters, 155 Halifaxes, 93 Sterlings, 55 Wellingtons and 12 D.H. Mosquito's. The ED928 was a so-called 'Pathfinder', a support aircraft. They were tasked with marking the target areas with red or green marker flares between the attack waves, so that after the first attack wave, the following formations would be able to differentiate the targets in between the fires that were caused by the first bombardment. For Paul David, the bomb-aimer, the night must have been special above all. He turned 23 that night.

Crash at Utrecht

While the enormous formations of planes were flying over the North Sea, the Luftwaffe's night fighters had already taken off to await the English aircraft over the Netherlands. They were guided towards the British bombers by radar stations. The moment visual contact was made, the German pilots would maneuver their aircraft into a favorable position and open fire. This would often happen from behind and below the bomber. This way the night fighter would remain out of sight of the gunners and could quickly dive away to make a new attack if needed.

ED928 was probably shot down by German fighter pilot Werner Baake, but it could also have been Georg Kraft. Both men were German night fighter pilots who claimed to have shot down a Lancaster near Utrecht. Most likely it was Werner Baake. It is also possible that both Germans shot at the same plane and only filed a claim after the plane crashed. This because although the bomber was hit, it did not immediately crash.

Thirty minutes after midnight, the roar of hundreds of aircraft engines on their way to Germany awoke the inhabitants of the Dom city. At 00:56 the battered Lancaster ED928 OR-B was spotted from the Utrecht Dom Tower, where a German observation post was located at the time. This information was then passed on to various authorities, such as the fire brigade, the air protection service, the police and other emergency services. The bomber went straight across Utrecht. The plane swept low over the houses with screeching engines and a lot of noise. Armstrong will have tried to keep the plane stable, so that his crew could save themselves with their parachutes. Five of the men managed to bail out before it exploded and crashed in the Wittevrouwen district of Utrecht. Alexander Laing probably managed to escape because he was in the tail turret. There was a special way the dome could be exited, in which Laing would have had to grab and put on his parachute, he then had to turn the dome and drop backwards into the dark night. Another possibility was that he left the plane through the access door, on the right-hand side in the rear part of the fuselage. Hanging on his parachute, he floated down.

Kwakman, a 20 year old man from Utrecht, stood watching the German anti-aircraft gun from 8 Takstraat. He too had seen a fireball heading directly for his neighborhood and for a moment he feared it might crush him. However, he was too curious to flee and breathed a sigh of relief when it turned out he was not in danger. He was in for a different, remarkable meeting, because in the meantime Laing was coming down on his parachute. He ended up in the walnut tree on the grounds of the Veterinary university, behind the garden wall of 2 Takstraat.

Curious, Kwakman and Frans van Veen, an older kid from the neighborhood, climbed over the wall and went to the parachutist. Laing had managed to free himself and he was bleeding heavily from a cut in his finger. Once he was helped over the wall, Laing was given shelter at 8 Takstraat. He was completely shaken by his experience. He told them that he was Alex Laing from Manchester. He also gave them all of his spare change and his home address. Kwakman considered hiding Laing at his house, but due to his injuries Laing was first taken to Nieuwenhuizen, a family doctor from the Biltstraat. This doctor offered the Englishman a glass of real brandy, which surprised the two boys! Later Laing was taken away by a member of the Grüne Polizei.

Another crew member who managed to escape the plane was Edward Bellis. He had been hit by three bullets and had several shrapnel fragments in his body. He lost consciousness during the fall, but he came too in time to open his parachute. After that he lost consciousness again and landed in a hay field outside of town. Because he did not want to endanger the Ginkel family, who had taken care of him at their home, he asked them to turn him in to the German military authority, which subsequently arrested him. In his diary, which he kept during his captivity, Bellis wrote:

"I had suffered minor injuries, after I was hit by three bullets and peppered with shrapnel fragments from exploding grenades. I left the plane in an unconscious state, regained consciousness while I was falling, but lost consciousness again after I pulled the cord of the parachute and eventually I regained consciousness and found myself lying in a hay field, about a quarter of a mile outside Utrecht. Around 10:30 that morning I was arrested by the SS and spent several days locked up in a room in Amsterdam, with little food. The following Sunday I was transferred to the Dulag Luft interrogation center near Frankfurt."

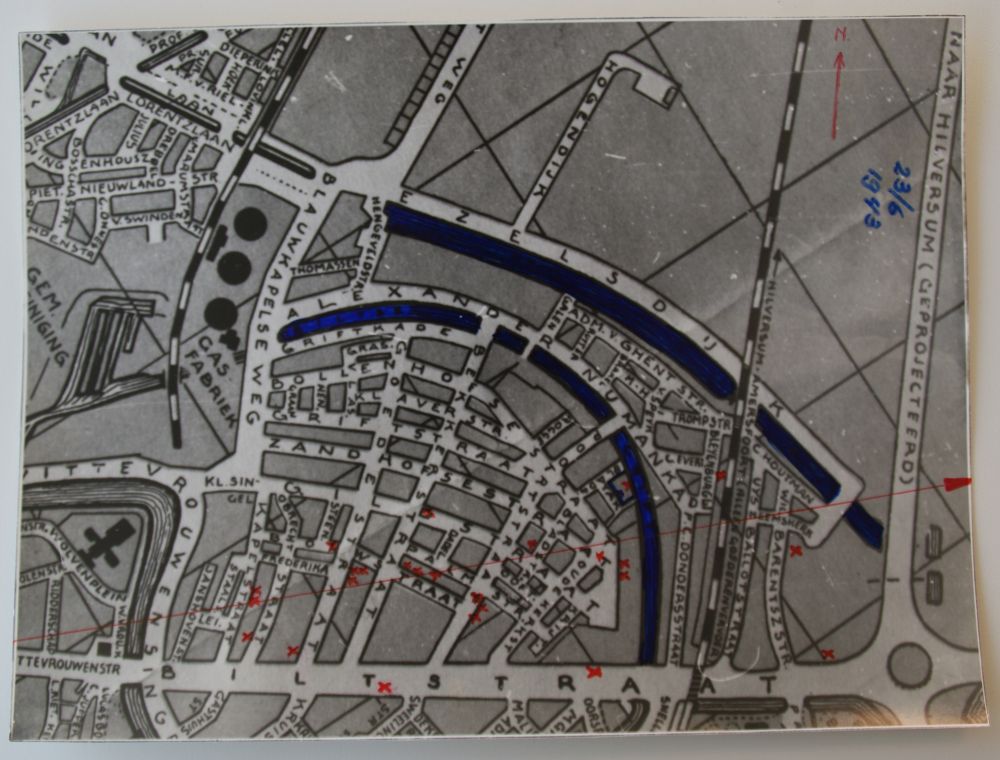

Flight direction of the bomber and the locations where debris and crew members came down. Source: Het Utrechts Archief

Victims and damage

Three of the crew members that escaped did not survive the fall. Possibly because their parachute did not slow their fall enough for various reasons or because they lost consciousness, just like Bellis, or because they were hit with debris. At the home of the Tomassen family, at 192 Bollenhofsestraat, the couple was sitting at the foot of their bed when a crew member crashed through the roof and landed on it. The parachute was found on the roof of 198 Bollenhofsestraat. A little further lay the tail wheel that had initially fallen down with the parachute of a crew member. At 29 Poortstraat another crew member fell to his death when he smashed into the facade of a house. He was very young and had blond hair, but was not identified on the spot like the others. The last crew member lay dead on the street in a pool of blood at 94 Gildestraat. His head had smashed against a wall when he landed.

The wreckage of the Lancaster came down as metal rain over the whole of the Wittevrouwen district. Various homes were damaged, mostly glass damage. Mrs. van Hes, who lived at 154 Gildestraat, described how her home was spared. "A chunk of the gas tank of the aircraft had fallen down and landed exactly on [the telephone wires], and like a spring mattress, the burning piece fell down past the edge of our roof onto the lower rear of our neighbors [house] at 2 Bladstraat." There was a lot of neighborly love and willingness to help each other. Mrs van Hes continued:

"The whole lot next to it caught fire soon after and bystanders and neighbors formed a chain in order to save what could be saved. Because of the stress a lot was being smashed, by roughly and too quickly throwing down what needed to be saved first. Almost all the crockery was smashed onto the street and they had almost nothing left. At our place a lot was grabbed together in a hurry and because this was rushed as well, my records flew in an arc through the room, but we survived the night despite everything."

The Maarschalkerweerd family, at 174 Zandhofsestraat, had a wheel crash on their doorstep. Across the street, at the Klaassen residence, a bomb dropped on the house according to Mr Klaassen and he needed help. Karel Maarschalkerweerd responded: "Well if what you are saying is true, I certainly am not going in to get it." When nothing happened, he decided to venture in nonetheless, to see what was lying inside. An oxygen cylinder lay hissing on the floor.

Karel Maarschalkerweerd points at the spot where the wheel of the Lancaster fell down, in front of his house at 174 Zandhofsestraat. Source: Co Maarschalkerweerd

In addition to the five crew members, five residents of Utrecht also lost their lives. Cornelis de Boer and Jacoba Verkerk lived at 49 Kapelstraat with their 12 year old son Johan. Their bodies were found on the afternoon of June 23 amongst the ruins of their house. The three family members were burned beyond recognition, but their identities were assumed because the parents and Johan had not been heard from by the families' other children who no longer lived at home.

The youngest victim was 4 year old Aart Stravers, from 47 Kapelstraat. Father Stravers was employed in Germany. The three oldest children of the Stravers family were awakened by the noise, but the youngest was not. From the mother's bedroom the family looked out of the front window, while at the same time the back of the bedroom was hit and caught fire, the blaze made it impossible to reach young Aart. An attempt to save him, by the eldest daughter Johanna, failed. The other family members managed to escape along the gutter. Johanna herself eventually jumped down in a panic after a burning curtain fell on top of her. She was brought to hospital in an ambulance to be treated for her burns. Mr. and Mrs. Van Emmerik, neighbors of the family, remembered this event:

"Mrs. Stravers was outside and kept calling 'The child is still up there'. We brought a large ladder but we could not reach it as everything was on fire because of the gasoline. The pear tree in our garden was completely ablaze as well. It was a terrible sight. Later on we saw another plane on fire, but that one luckily went into a different direction."

A tragic victim was 79 year old Mr. Cornelis van Heelsum, who lived at 20 Obrechtstraat. Debris of the bomber hit the roof and the front of the house and drove a hole all the way to the ground floor. Mr. van Heelsum was startled awake in the dark and got out of bed, where he fell through the hole to the ground. He died from his injuries.

Despite the attempts of the fire brigade and the neighbors, six homes were completely destroyed: 47 and 49 Kapelstraat, 37 and 39 Bouwstraat, 20 and 61 Obrechtstraat. The families living here were sheltered at the school at 73 Poortstraat. On the grounds of the Veterinary School two bombs had come down which needed to be cleared. If these bombs had exploded, the situation would have been much more disastrous than it already was. On top of all the misery, someone saw the situation as an opportunity to steal a bicycle from 67 Goedestraat. The smallest amount received by the victims was 4 guilders for damage to the windows of 36D Goedestraat, a home for poor families, owned by Mr. A.G.E. Asch van Wijck. The largest amounts, between 3000 and 3200 guilders, were paid to the owners of 47 and 49 Kapelstraat, the homes that were completely destroyed. The total damages were estimated between 28.409,50 and 30.259,50 guilders.

Afterwards

Of the bombers that took part in the action, 58 did not reach their target. This could have been because of technical malfunction, or due to illness of a crew member. In total, 39 aircraft were lost, including the ED928 of the 97th Squadron. In total 64% of the cities of Mulheim and Oberhausen were destroyed. In both cities 578 people were killed and no fewer than 1174 were injured. 1135 houses were destroyed, 12.637 houses were damaged to greater or lesser extent. Also, 41 public buildings were hit 27 schools, 17 churches and 6 hospitals.

and Bellis survived the war as prisoners of war. While they were held in the Dulag Luft interrogation center they got little to eat. Bellis wrote that he got three or four rotting potatoes and some sandwiches for lunch and breakfast. Afterwards they were held in several different camps. Two of them were Stalag Luft 6 in Heydekrug, nowadays Silute in Lithuania, and Stalag 357 ("Kopernikus") in Thorn, nowadays Torun, Poland, Initially the food had been better, but by the end it was so bad that Laing ended up with an ulcer. He was liberated in the vicinity of Aachen. Bellis died in the first half of the 90s. Laing died when he was 33 years old.

Cornelis van Heelsum was buried with his wife at the Den en Rust cemetery in Bilthoven. The grave is a silent witness to the Second World War, like many others that can be found on Dutch cemeteries. Because victims like these are not formally recognized as victims of war, the graves of victims of bombings and plane crashes threaten to disappear without an intervention of a municipality or other authority. The young Aart Stravers was buried on the 28th June 1943 at the Soestbergen General Cemetery in Utrecht. The De Boer family was buried on the 26th of June 1943 in a communal grave, but they were later transferred to a private grave.

Werner Baake downed his last aircraft on January 5, 1945, a Handley Page Halifax. He scored a total of 41 kills. He survived the war and became a pilot for Lufthansa. He lost his life on July 15 1964 in an air crash, along with two other crew members.

In 2016, a plaque was unveiled at 47 Kapelstraat by mayor Jan van Zanen together with the then resident of the house. The commemorative plaque reminds the reader of the events that happened in the Wittevrouwen district at the time. The crew members who were killed are buried at Soestbergen Cemetery on the Koningsweg.

Definitielijst

- raf

- Royal Air Force. British air force

- Squadron

- A military unit in the Belgian navy usually six to eight small ships operating together under one command. The smallest military unit in the Dutch air force of about 350 men. In most countries is the designation of a military unit thesize of a company. It is either an independent unit, such as a battery, or part of a bigger Calvary unit. In the air force it is the designation of a unit of aircrafts.

Information

- Article by:

- Samuel de Korte

- Translated by:

- Marieke Feller

- Published on:

- 24-12-2018

- Last edit on:

- 21-11-2023

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related books

Sources

- MIDDLEBROOK, M. & EVERITT, C., The Bomber Command War Diaries, Pen & Sword Books Ltd, Barnsley, 2014.

- Het Utrechts Archief, 1105 Verzameling historisch werkmateriaal van Het Utrechts Archief, 146 Stukken, ingekomen bij en verzameld en opgemaakt door A. Cocural, naar aanleiding van een onderzoek naar het neerstorten van een Engelse bommenwerper, type Avro-Lancaster B. III, op 23 juni 1943 in de wijk Wittevrouwen te Utrecht, 1973-1976, met foto’s (34), 1943, met name reproducties, ca. 1975.

- Het Utrechts Archief, 92310, J. E. Spruit, Lancaster, (2011).

- Maarschalkerweerd, J.C., "Een nacht… Een Lancaster", ’40-’45 Toen & Nu, 44-49. Met dank aan Co Maarschalkerweerd.

- World War II Allied Aircraft Crashes in The Netherlands & North Sea

- RAF Pathfinders Archive