Prologue

Tirpitz was the second Bismarck class battleship that was built for the Kriegsmarine. Her keel was laid on November 2, 1936 at the Kriegsmarinewerft in Wilhelmshafen. She was launched on April 1, 1939 and commissioned on February 25, 1941 by her commander, Kapitän-zur-See Friedrich Karl Topp. Until that date, the R.A.F. had already launched numerous air raids with twin-engine Handley Page Hampden and Vickers Wellington bombers. Construction of the mighty German vessel could not be delayed nor prevented by these attacks though. Before the battleship could start her sea trials, she was subjected twice to British air raids but with little effect though. Over the year 1941, her 2,065 crewmembers were trained for their tasks aboard the battleship. On May 5, 1941, Adolf Hitler personally paid a visit to the two Bismarck class battleships in Gothenhafen, the former Polish port of Gdynia on the Baltic, occupied and renamed by the Germans. 11 days later the Bismarck, accompanied by the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, set sail from Gothenhafen to meet her destiny. Both ships had been ordered to attack Allied convoys in the North Atlantic but were being pursued by the British Home Fleet. On May 27, 1941, Bismarck was sunk by an overwhelming British force.

| The sister ships Bismarck and Tirpitz were the largest and most heavily armed German battleships of World War Two. Both ships had a standard displacement of 42,000 tonnes and were almost 820 feet in length. They were heavily armored but nonetheless able to reach a maximum speed of 30 knots from their 12 Wagner high pressure boilers and three powerful steam turbines. The vessels were armed with eight 15 inch guns in four twin turrets, 12 guns of 6 inch and 16 guns of 4 inch. In addition the vessels were equipped with dozens of anti-aircraft machineguns and four spotter planes. The crews numbered over 2,000 officers and men. |

On November 13, 1941, Großadmiral Erich Raeder, Commander-in-Chief of the Kriegsmarine proposed to station the Tirpitz in the north of Norway to pose as Fleet in Being once her trials were completed. The presence of the battleship would force the British Home Fleet to protect the Arctic convoys sailing from Iceland and Scotland to Murmansk in the Soviet Union. This way, the British fleet would not interfere in a possible recapture of strategic highly important Norway. Hitler approved as he had forbidden the Tirpitz to venture out in to the ocean following the loss of her sister ship Bismarck. The armament of the vessel was expanded and Tirpitz set sail for Trondheim in Norway on January 1942, escorted by four destroyers. The British were informed of the departure of the Tirpitz and her escort as in the meantime, they were able to decipher the Enigma codes. Owing to bad weather, the R.A.F. was unable to take any action. Two days later, the German war ships were spotted in Trondheim by a British reconnaissance plane but the ship left the very same day for the Faettenfjord north of Trondheim. On arrival, the Tirpitz dropped anchor in a sheltered spot and was camouflaged with nets. A number of anti-aircraft batteries were established on the cliffs above the fjord and torpedo nets were rigged around the vessel.

A fortnight later, R.A.F. Bomber Command launched Operation Oiled, the first aerial attack on the Tirpitz in Norway. Owing to bad weather however, the attack by British Short Stirling and Handley Page Halifax bombers ended in failure. But the Tirpitz launched failed attacks of her own as well on Allied convoys. The most important attempt was code named Operation Sportpalast and was launched in March 1942. Tirpitz and her destroyer escort only managed to find and sink one Allied merchantman before the German battleship herself almost fell victim to British carrier based fighters. Tirpitz safely returned to the Fjaettenfjord on March 13. Over the next 3 months, the vessel was attacked three times by the R.A.F. but each time, bad weather caused the attacks to fail.

During Operation Rösselsprung, nearly all large surface vessels were deployed to attack two heavily guarded Allied convoys. The German war ships set sail from the Norwegian fjords. The British considered the threat of the German vessels so dangerous, they ordered the convoy to scatter and proceed to Murmansk on their own (convoy PQ 17 Ed.). This turned out to be a catastrophic blunder as over half of the merchantmen were sunk by German aircraft and U-boats. Just the threat of the large German surface vessels had been enough for the navy to abandon the Allied convoy.

In the fall of 1942 the Tirpitz underwent maintenance, at anchor in the Faettenfjord. In this period, the Tirpitz was attacked by the British and the Norwegians with so-called chariots, human torpedoes. These attacks also ended in failure due to bad weather.

In February 1943, the battleship Scharnhorst arrived to reinforce the German navy in Norway and together with the Tirpitz, the vessel carried out an attack on British bases and weather stations on the island of Spitsbergen. During this attack – Operation Sizilien – both war ships were protected by 10 destroyers. After the attack, the German warships returned to their hide out in the Norwegian fjords. The Tirpitz berthed in the Kaafjord, a tributary of the Altafjord in the extreme north of Norway. Although Operation Sizilien had not had that much effect on the progress of the war in Norway, the threat of the Tirpitz, the Lonely Queen of the North, as the vessel had been dubbed by the Norwegians in the mean time, could not be ignored.

Definitielijst

- battleship

- Heavily armoured warship with very heavy artillery.

- Bomber Command

- RAF unit which controlled strategic and sometimes tactical bombing (as in Normandy)

- cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

- destroyer

- Very light, fast and agile warship, intended to destroy large enemy ships by surprise attack and eliminating them by using torpedoes.

- Enigma

- Cryptographic (de)coding machine used by the Germans during World War 2. The code was broken by the British with help from the Poles. Much German military information was known to the British in advance. This was a huge aid to the war effort.

- Fleet in Being

- A war fleet preventing battle but by its presence and force forcing the enemy to take measures by allocating forces to keep an eye on them thus preventing those forces from being deployed elsewhere.

- Kriegsmarine

- Germa navy. Part of the Wehrmacht next to Heer and Luftwaffe.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

Images

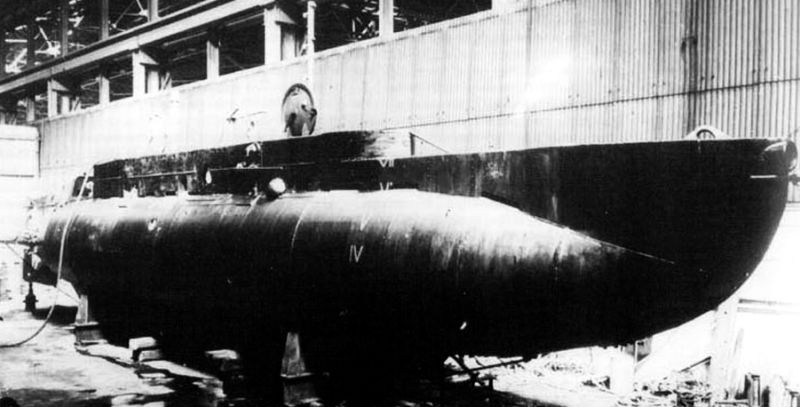

An X-craft on exercise. Source: Navy News.

An X-craft on exercise. Source: Navy News. Tirpitz on sea trial on the Baltic Sea. Source: Bundesarchiv.

Tirpitz on sea trial on the Baltic Sea. Source: Bundesarchiv. German surface vessels Tirpitz, Admiral Hipper and Admiral Scheer on their way for Operation Rösselsprung, July 1942, Source: Courtesy of Michael W. Pocock.

German surface vessels Tirpitz, Admiral Hipper and Admiral Scheer on their way for Operation Rösselsprung, July 1942, Source: Courtesy of Michael W. Pocock. Tirpitz at anchor in the Kaafjord. Source: Bundesarchiv.

Tirpitz at anchor in the Kaafjord. Source: Bundesarchiv.British attack by midget submarines

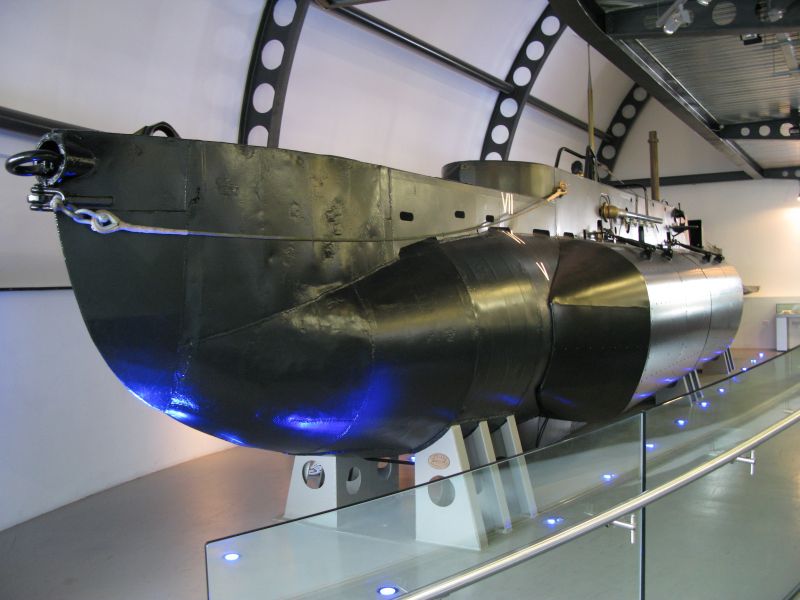

As the aerial attacks on the Tirpitz had all been in vain so far, the British decided to risk an attack on the German battleship using midget submarines or X-craft. In the summer of 1943, the 12th Submarine Flotilla, Royal Navy underwent a specialized training. The 6 X-craft, allocated to Operation Source, were to be towed to Norway by conventional submarines. Living conditions aboard the midget subs were so deplorable, the crews would be totally exhausted if they would have to make the passage themselves. Ample reason to man the X-craft by a relief crew during the voyage and replace them by the operational crew shortly before the attack.

| X-craft midget submarines: H.M.S. X-5 to X-10 all belonged to the X-5 subclass of the British X-class midget submarines. The entire subclass was built in the Vickers Armstrong dockyard at Barrow-in-Furness, England. The midgets displaced 30 tonnes submerged and an over all length of 51 feet. On the surface, the vessels were propelled by a single 40 hp Gardner 4 cylinder diesel engine, giving them a maximum speed of 6.5 knots and a range of 500 nautical miles. Submerged, they were propelled by a single Keith Blackmann electric engine which could deliver 30 hp. The batteries to drive the engine were being charged when the midgets sailed on the surface on the diesel engine. Submerged, the X-craft reached a maximum speed of 5.5 knots and a range of a mere 80 nautical miles. The midgets were tested to a maximum depth of 300 feet. The armament of the X-craft consisted of two detachable explosive charges of 2,200 lbs of Amatol each, attached to either side of the vessel. |

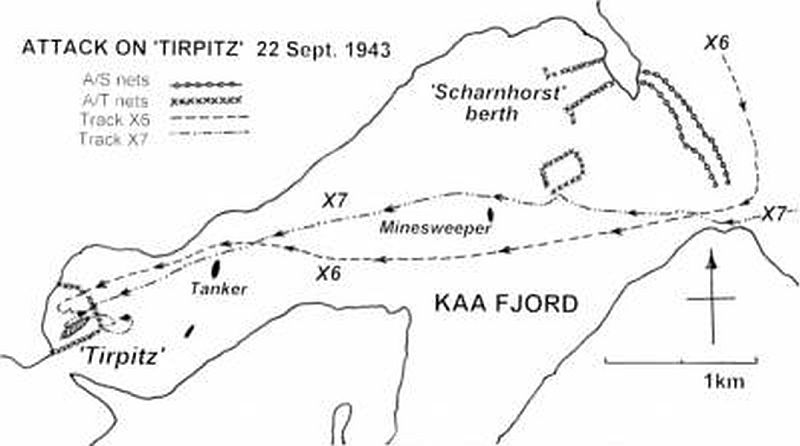

The conditions in the northern Norwegian fjords as to weather, the position of the moon and the period of darkness would be most favorable between September 20 en 25. Hence it was decided that September 19 would be the last day to detach the midgets from the towing subs and to replace the crews. In order to make it on time, departure of the subs from Loch Cairnbawn in Scotland was set on September 11, 1943. Towing the midgets fell to the submarines H.M.S. Thrasher, Truculent, Syrtis, Seanimph, Stubborn and Scepter. In preparation for the operation the 6 midget submarines H.M.S. X-5 to X-10 were hoisted aboard the depot vessel H.M.S. Bonaventura 5 days before. Here the midgets were prepared and fitted with the Amatol explosives. In addition to the Tirpitz the German battleship Scharnhorst and the heavy cruiser Lützow in the Kaafjord were to be attacked by the 6 midgets as well.

At 16:00 hours on September 11, 1943, H.M.S. Truculent with X-6 in tow and H.M.S. Syrtis towing X-9, set sail from a position 75 nautical miles west of the Shetlands where they had taken over the midgets from H.M.S. Bonaventura. Next, every 2 hours H.M.S. Thrasher left with X-5, H.M.S. Seanimph with X-8 and H.M.S. Stubborn with X-7 in tow. Last to leave was H.M.S. Scepter at 13:00 hours on September 12 with X-10 in tow. The four-day trip to the next rendezvous point proceeded well and the 12 submarines all reached the position 150 nautical miles west of Altafjord. During the passages, the targets for the individual midgets were determined using aerial photographs. X-5, 6 and 7 were to attack Tirpitz, X-9 and 10 Scharnhorst and X-8 Lützow. On September 15, the submarines towed the midgets in the direction of the Altafjord short of the German minefields. The towing cable between H.M.S. Syrtis and H.M.S. X-9 snapped however and the crew of Syrtis only found a trace of oil during their search for the midget submarine. H.M.S. X-9 and her three-men relief crew went missing without a trace. Two days later, H.M.S. X-8 encountered technical problems and as a result of leakage in the explosive charges, it was decided to detach them from the midget and detonate them so the midget itself could be salvaged. The explosion caused so much damage to X-8 however that she was scuttled. The crew got aboard H.M.S. Seanimph safely.

At sunrise on September 20, the remaining midgets reached their starting points at some 60 nautical miles west of the Altafjord without further problems. From then onwards, the X-craft had to find their own way through the minefields, hiding submerged during daylight and the next day, again at sunrise, enter the Kaafjord. Between 18:30 and 20:00 hours in the evening of September 20, the 4 X-craft detached themselves from the towing subs and proceeded towards the Soroy Sound, the entrance to the Altafjord. Lieutenant Henty Creer, commander of H.M.S. X-5 shouted his wishes of good luck to the commander of H.M.S. X-7, Lieutenant Place. This was the last time the British heard anything about the X-5. H.M.S. X-10, commanded by Lieutenant Hudspeth encountered technical problems and the crew attempted to sort them out but without much success though. As H.M.S. X-8 and H.M.S. X-9 had already been lost earlier and H.M.S. X-10 no longer being available, the British Navy was forced to cancel the attack on the Scharnhorst and the Lützow. X-10 was found on September 27 by H.M.S. Stubborn in the Ofjord and both vessels turned for home. As X-10 was unable to make the passage back to Scotland, it was decided to scuttle the vessel and take the crew in aboard the Stubborn.

Commander Lieutenant Donald Cameron managed to guide his X-6 through the minefields and took up position off the Brattholm islands, a group of rocky islands at the entrance of the Kaafjord in the evening of September 21 to lie in wait. Lieutenant Place equally managed to steer his X-6 safely past the German sea mines and saw the Scharnhorst leave the Altafjord at 16:30 hours. He also took up a safe position off the Brattholm islands to wait for the night but did not make contact with Lieutenant Cameron.

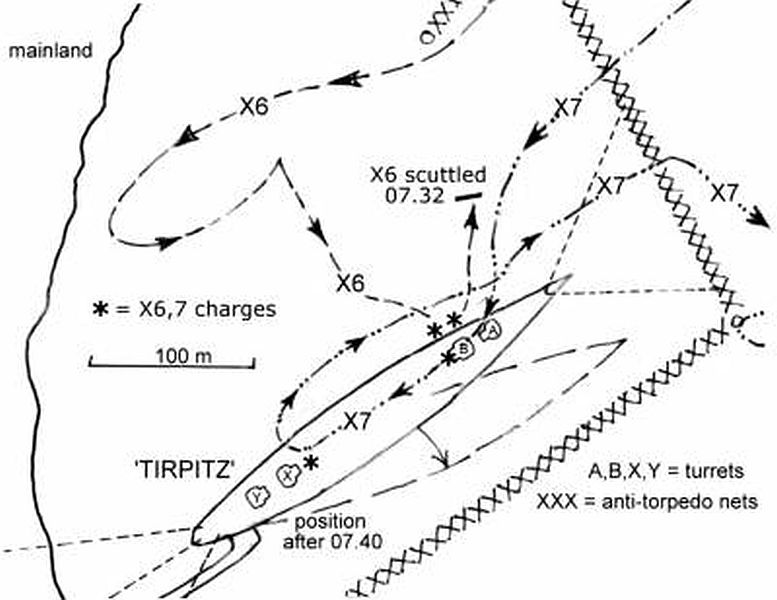

Two torpedo nets were strung around the Tirpitz. Just before sunset on September 22, the outer boom was opened to let a coaster pass. Commander Cameron of X-6 reacted quickly by diving behind the coaster and sneaking through the opening before the boom was closed. Despite the fact his periscope and gyroscope did not function, his midget struck an unchartered rock under water and he was being spotted by guards aboard Tirpitz, he did manage to get his X-6 beneath the Tirpitz, place his charges and arm them. As he and the other crew members of the midget realized escape was impossible, they scuttled X-6 and surrendered. The 4 British sailors were apprehended and taken aboard the Tirpitz.

X-7, commanded by Lieutenant Basil Godfrey Place got entangled in one of the torpedo nets but did manage to place its explosives and arm them. On the way back the midget, badly damaged by a depth charge got entangled in the net again. Two members of her crew managed to escape from the vessel but the other two found a seaman's grave in the midget. The vessel sank and the two survivors, including Place, were apprehended as well and transferred to the German battleship.

The crews of the six X-crafts:

|

After the war, the captured crew members of H.M.S. X-6 and X-7 returned to Great Britain safely. The commanders of both midgets, Lt Cameron and Lt Place were awarded the Victoria Cross, Britain's highest award for courage displayed during Operation Source. Lt Lorimer and the Sub-Lts Aitken and Kendall were awarded the Distinguished Service Order and Artificer Goddard was presented with the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal for services rendered.

Definitielijst

- battleship

- Heavily armoured warship with very heavy artillery.

- cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

Images

An unknown X-craft during a trial run. Source: Navy News.

An unknown X-craft during a trial run. Source: Navy News. An X-craft comes alongside a surface vessel, Navy News Source: Navy News.

An X-craft comes alongside a surface vessel, Navy News Source: Navy News. An X-craft undergoing maintenance. Source: Navy News.

An X-craft undergoing maintenance. Source: Navy News. F.l.t.r. Lt. L. Martin, Lt. K.R. Hudspeth, Lt. B. McFarlane, Lt. B.G. Place and Lt. D. Cameron. Source: Navy News.

F.l.t.r. Lt. L. Martin, Lt. K.R. Hudspeth, Lt. B. McFarlane, Lt. B.G. Place and Lt. D. Cameron. Source: Navy News. The cramped interior of an X-craft. Source: Navy News.

The cramped interior of an X-craft. Source: Navy News.Aboard the Tirpitz

Aboard the German battleship, the day had started like any other. The hydrophone watch was ended at 05:00 to perform maintenance on the underwater listening device. As the hydrophones were out of action, additional lookouts were positioned on deck. At 07:07, a slight disturbance on the surface of the water inside the torpedo nets was spotted but it was done away with as a surfacing porpoise. In reality, the lookouts of the Tirpitz had spotted the movement in the water when H.M.S. X-6 struck the under water rock. At 07:12, X-6 was identified as an enemy submarine when she surfaced again for a few moments. A lifeboat was manned and launched quickly. At the same moment the alarm was sounded aboard the battleship. A mistake was made here because instead of sounding the right number of bell tones, indicating danger from a submarine, the alarm for closing watertight hatches and doors was sounded. Hence, the majority of the crew was not aware of the real danger. As the midget was so close to the battleship, she was out of range of her guns and the crew of the Tirpitz could not prevent her from submerging again. A few minutes later, the midget surfaced again and the lifeboat came alongside immediately. The Germans arrested the crew but could not prevent them from scuttling the midget. As the prisoners were very dejected, the Germans thought they had prevented possible bad intentions. As they were unaware that X-6 had set her charges, the order was given to make steam instead of casting off immediately.

At 07:40 a second midget submarine was spotted. It was H.M.S. X-7 attempting to escape through the net after having set her deadly charges. The midget came under fire from anti-aircraft machineguns and was plastered with depth charges by the destroyers Z 27 and Z 30. Heavily damaged by one of the depth charges, X-7 got entangled in the net and two British survivors were arrested as well. Unsure of the fact whether the battleship was undermined or not, her commander Kapitän-zur-See Hans Meyer ordered Tirpitz to be turned away from possible danger by swinging her to starboard using her anchors and mooring wires. He had quickly realized that steaming away at very short notice was impossible as it would take at least an hour before the engineers could have put up enough steam.

At 08:12, two massive underwater explosions sounded almost simultaneously. The German battleship was lifted almost 3 feet out of the water. An oil tank was torn open and armor plating was buckled. A large hole was blown in the double bottom of the vessel and some 1,400 tonnes of freezing water rushed in. As a result, both generator compartments were flooded and all but one turbo generator were rendered inoperable causing almost all electric power to fail. The shafts of the screws seized in their bearings and two of the 38cm turrets were lifted from their foundations. Various anti-aircraft batteries became unusable, range finders and fire control equipment were dislodged and all radar failed. Two of the 4 Arado spotter planes were blown overboard and utterly destroyed. In this chaos, a third midget was spotted at 08:43, some 710 yards from the severely damaged battleship. German destroyers and Tirpitz' still usable anti-aircraft guns opened up immediately on the vessel just spotted. In all probability, this was H.M.S. X-5 which had taken up position outside the torpedo nets to starboard of the Tirpitz to await her chance to place the explosives in her turn. The midget submerged after having been hit a few times and was subsequently plastered with depth charges by Z 27. Neither her crew, nor the wreckage of the midget were ever found.

The Kriegsmarine dispatched 2 generator vessels, the Karl Junge and the Watt to the Tirpitz which by now listed 30 degrees. Karl Junge arrived the same day from the Langefjord. On September 25 the German Navy staff decided, with permission by Hitler himself, the Tirpitz was to be repaired on the spot. Yet everyone agreed, the German vessel could no longer be made 100% operational and seaworthy again because a large number of frame beams had been buckled as a result of the heavy explosions and these could not be replaced without the vessel having to be put in dry dock for a very long time. Nonetheless, crew members of the Tirpitz and technical specialists from the repair- and supply vessel Neumark managed to repair the Tirpitz to an acceptable operational level within 6 months. Without the help of heavy cranes and a dry dock, in the middle of winter and far beyond the Arctic Circle, this was an extraordinary achievement.

Definitielijst

- battleship

- Heavily armoured warship with very heavy artillery.

- Kriegsmarine

- Germa navy. Part of the Wehrmacht next to Heer and Luftwaffe.

- radar

- English abbreviation meaning: Radio Detection And Ranging. System to detect the presence, distance, speed and direction of an object, such as ships and airplanes, using electromagnetic waves.

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

Images

Another picture of Tirpitz in the Kaafjord, surrounded by torpedo nets, March 1943. Source: Courtesy of Michael W. Pocock.

Another picture of Tirpitz in the Kaafjord, surrounded by torpedo nets, March 1943. Source: Courtesy of Michael W. Pocock. Drawing of the attack on Tirpitz. Source: Warfare Magazine.

Drawing of the attack on Tirpitz. Source: Warfare Magazine. Drawing of the attack on Tirpitz. Source: Warfare Magazine.

Drawing of the attack on Tirpitz. Source: Warfare Magazine.The end of the Tirpitz

As Winston Churchill had given highest priority to the destruction of the Tirpitz, attacks on the German battleship continued relentlessly. On December 26, the Scharnhorst went down first in the battle for the North Cape. Shortly afterwards, Lützow and most destroyers stationed in Norway were recalled to Germany. The Allies, headed by the British could now concentrate on the Tirpitz still under repair. In the night of February 10 and 11, she was attacked by Soviet bombers but those could only report just one indirect hit. A few months later, Tirpitz concluded her first sea trials and on April 3, she was at anchor again behind the torpedo nets in the tributary of the Altafjord.

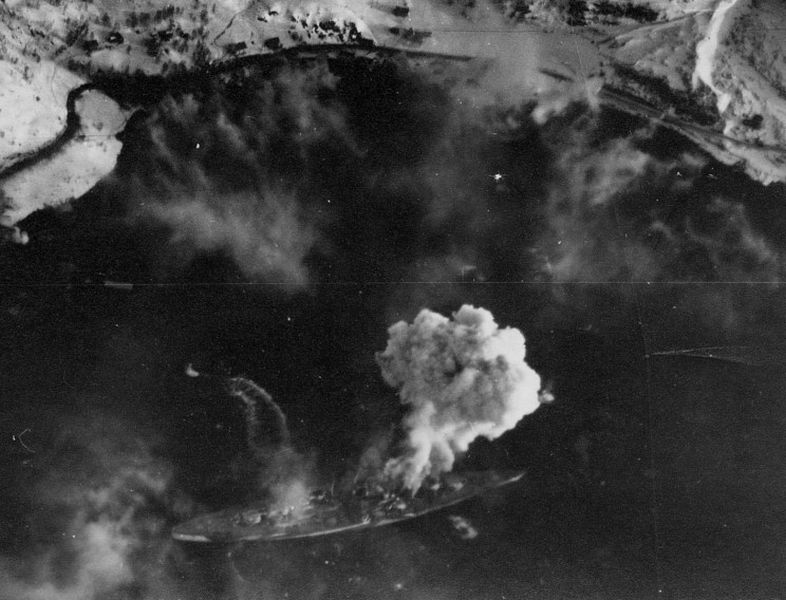

The Royal Navy attacked the battleship with dozens of carrier based planes in Operation Tungsten. The battleship received 14 hits and a near miss with bombs of 1,600 and 500 lbs. 122 crew members lost their lives and over 300 were injured aboard the vessel that suffered even more damage to her buckled frame beams. 2,000 tonnes of water flooded in, two 15cm turrets were knocked out and the two remaining spotter planes burned to ashes in their storage. The decks of the apparently indestructible vessel had not been penetrated however and the battleship was still operational. The Tirpitz was repaired once again and her threat remained.

Subsequent planned operations, code named Planet, Brawn and Tiger Claw failed due to adverse weather conditions. Operation Mascot, launched on July 17, 1944 failed because the Germans were alerted to the attacks by advanced radar technology. They laid thick smokescreens, completely hiding the battleship from the bombers. In August, the Royal Navy undertook the last attempts to knock out the Tirpitz. Operations Goodwood I, II, III and IV all amounted to nothing. The bombers of the Royal Navy were only able to score two hits in total.

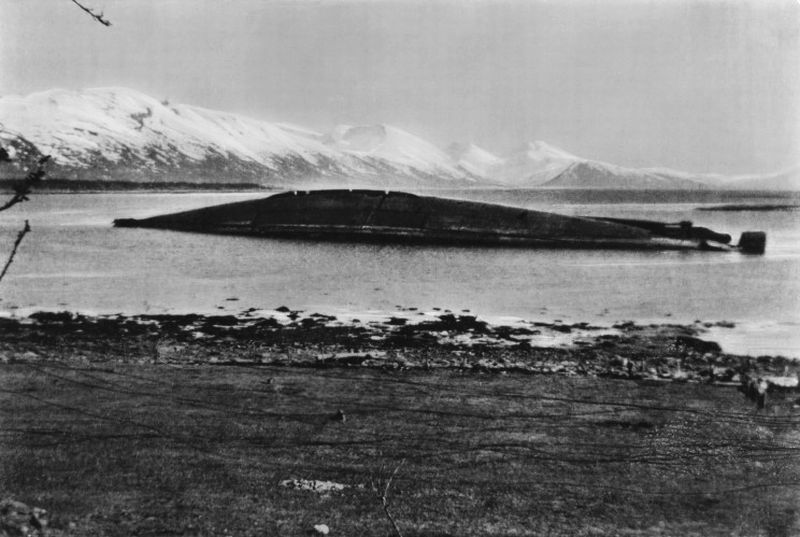

Meanwhile, the R.A.F. had prepared plans to attack the battleships with the new Tallboy bombs. These were specially designed 12,000 lbs bombs that, once dropped, reached extremely high speed by their rocket shaped streamline and tailfins. This enabled the projectiles to penetrate deeply into concrete bunkers and armored steel decks before exploding. On September 11, 38 four-engine Lancasters launched Operation Paravane, flying via Archangelsk in northwestern Russia to the Altafjord and releasing 20 of these newly developed bombs. As the Germans were alerted again and laid thick smokescreens, Tirpitz was hit on the forecastle by only 2 bombs. The two bombs penetrated the bow of the vessel however and detonated beneath the ship on the bottom of the fjord. This time, the damage caused to Tirpitz was massive. Engines and fire control equipment were as good as knocked out and the already heavily damaged frame beams suffered even more irreparable damage.The German navy leadership quickly concluded the battleship could never be made seaworthy again. Therefore it was decided to transfer the vessel, after emergency repairs had been made, to the island of Håkøy near Tromsø to serve as a floating artillery emplacement against the expected Allied recapture of Norway. The German Admiralty had not realized however, the battleship was now within range of Lancasters flying from R.A.F. Lossiemouth in Scotland. After a failed attack with Tallboys, Operation Obviate on October 29, the R.A.F. launched Operation Catechism on November 12, 1944. Out of the 31 attacking Lancasters, 29 were able to drop bombs on the Tirpitz. Two of those were direct hits and a lone Tallboy scored a near miss. This caused Tirpitz to list to port which quickly increased to 20 degrees. Her list increased to 60 degrees and for a moment it looked like the battleship would stabilize itself in this position but a violent explosion sealed the fate of Tirpitz. The vessel capsized and her superstructure disappeared into the sandy bottom. Over 1,000 crewmembers got trapped in the armored hull of the battleship. Surviving technical specialists, dockyard workers and other navy personnel managed to make a few openings in her keel with blow torches, enabling 82 trapped crew members to escape. For 971 members of her crew, rescue came too late due to the freezing water rushing in at high tide.

The threat by the Lonely Queen of the North was finally over. Partly owing to the midget submarines and their extremely courageous crews, who had surprised the battleship in the fall of 1943, the Arctic convoys were now able to make the safe passage to Murmansk and back safely.

Definitielijst

- battleship

- Heavily armoured warship with very heavy artillery.

- radar

- English abbreviation meaning: Radio Detection And Ranging. System to detect the presence, distance, speed and direction of an object, such as ships and airplanes, using electromagnetic waves.

- rocket

- A projectile propelled by a rearward facing series of explosions.

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

Images

Tirpitz under fire during Operation Tungsten. Source: Courtesy of Michael W. Pocock.

Tirpitz under fire during Operation Tungsten. Source: Courtesy of Michael W. Pocock. The wreck of the Tirpitz near the isle of Hakoy. Source: Courtesy of Michael W. Pocock.

The wreck of the Tirpitz near the isle of Hakoy. Source: Courtesy of Michael W. Pocock. H.M.S. X-24 in the Submarine Museum in Gosport, southern U.K. Source: Wikipedia.

H.M.S. X-24 in the Submarine Museum in Gosport, southern U.K. Source: Wikipedia. A work of art in honor of the X-craft that successfully attacked Tirpitz. Source: Submarine Museum.

A work of art in honor of the X-craft that successfully attacked Tirpitz. Source: Submarine Museum.Information

- Article by:

- Peter Kimenai

- Translated by:

- STIWOT translator

- Published on:

- 23-06-2019

- Last edit on:

- 30-09-2024

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Related books

Sources

- GRöNER, E., German Warships 1815-1945, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland, 1990.

- HORE, P, Slagschepen, Veltman Uitgevers, Utrecht, 2006.

- LYON, H, Encyclopedie van de belangrijkste oorlogsschepen ter wereld, Scriptoria, Antwerpen, 1980.

- MALLMANN-SHOWELL J.P., Das buch der deutschen kriegsmarine 1935-1945, Motorbuch verlag, Stuttgart, 1995.

- STERN, R.C., Kriegsmarine, Arms & Armour Press, London-Melbourne, 1979.