Dave Hersch, Escape from a Death March

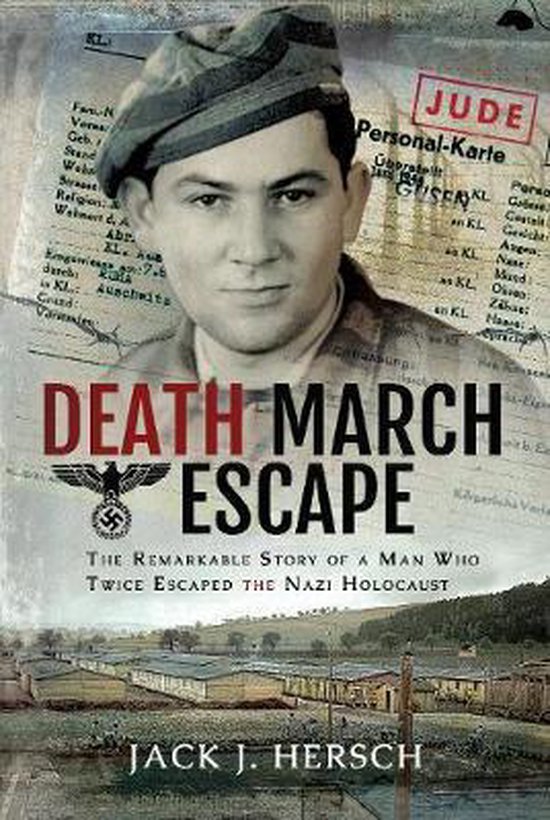

The following true story is written by Jack Hersch, son of Holocaust survivor Dave Hersch. He has written a book about the war time experiences of his father, that was published in 2018 by Frontline Books as "Death March Escape". More information can be found at the website deathmarchescape.com.

My father, Dave Hersch, spent the last year of World War II slaving in Mauthausen Concentration Camp, self-rated by the Nazis as the harshest, cruelest labor concentration camp in the entire Reich. Near the end of that year, in April 1945, he escaped from a death march originating at the camp. Recaptured, and inexplicably – perhaps miraculously – not killed for it, he was returned to Mauthausen. Placed on another death march the following week, he escaped again. This time he was found by a local family and, at the risk of their lives, hidden until the US Army’s 65th Infantry Division liberated the town. This is the story of my father’s first escape.

My father at 17: My father, in a photo taken when he was 17, one year before being sent to Mauthausen. The photo appeared on the Mauthausen website in 2007 and launched me on my journey about his story. Source: Jack Hersch

At the start of the war, it seemed the Jews of Hungary were going to miss the worst of the Holocaust visited on the rest of Europe. The Hungarian Regent, Miklos Horthy, had steadfastly refused to deport the Jews living in his cities and towns to death camps and concentration camps, and the Nazis tired of pressing the issue. But in the spring of 1944, after catching Horthy trying to negotiate a separate peace with the Allies, the Nazis took control and quickly made up for lost time. Within weeks, more than half of Hungary’s 800,000 Jews had been shoved into cattle cars, most shipped to Auschwitz Concentration Camp to be killed immediately, the others forced into slave labor.

My father was among the latter. On June 6 1944, the same day 150,000 Allied soldiers assaulted Normandy, he was sent first to Auschwitz, and a few days later on to the granite mines of Mauthausen, in Western Austria. He arrived exactly one month before his eighteenth birthday. Granite mining was backbreaking, soul-sucking labor in the best of times, but the Nazis made it worse. By imposing horrific treatment and a starvation diet on the prisoners, the Nazis used Mauthausen to slowly kill resistance members, communists, intellectuals, common criminals, incorrigible Allied POWs, gays, gypsies, and of course Jews.

By late winter 1945 my father, slim and of average height before the war, had been whittled down to under 80 lbs. And he was fighting typhus, tuberculosis and pneumonia. Then, in the first week of April they assigned him to that first death march, along with around 750 other Jews from the camp.

In telling his story, my father never actually called it a death march. Though now a well-known feature of the Nazi killing machine, he’d never heard the term. He called them what the Nazis always called them, a transport. It’s a German word that means essentially the same in English, a way of getting from one place to another. He learned he was going to be marched to Gunskirchen Concentration Camp, to get him and the other Jews on his transport away from approaching Allied armies.

Gunskirchen, near the Austrian town of the same name, was thirty four miles southwest of Mauthausen. It eventually held more than 20,000 Jews during the last few weeks of the war, death-marched there from Mauthausen and other labor camps near Russian and American army front lines. The camp was a nightmare. Wildly overcrowded, it had no running water, very little food, and not nearly enough shelter for so many people. Given his health, my father’s odds of surviving the march were slim. And even if he made it to Gunskirchen, his chances of remaining alive for the next month till the Americans liberated it were just as poor.

As the march began, my father fell into place with two old friends, brothers from his hometown. The younger one, bespectacled and slight, Izsak Moses had been in Mauthausen with him since the start. The older one, tall and broad-shouldered, Chaim Moses, had arrived a few days earlier on a 100 mile death march that had begun in Hungary. Chaim had spent the past year in a Hungarian Labor Service battalion repairing roads, bridges and railroad track, and was, compared to his brother and my father, in good shape.

The first two miles of the march were a long descent from the hilltop camp to the north bank of the Danube River. A mile further on they crossed a bridge to the south side, and the road became mostly flat. My father felt well enough for these first miles and the trio held together. But on the straight flat stretch his strength leaked away. Chaim took his elbow. When that wasn’t enough, he slipped a powerful arm under my father, supporting him. Bus soon that wasn’t enough either. My father told him to let go, imploring him to save his energy for his brother instead. He slipped out of the stronger man’s grasp.

Dragging himself weakly, my father made it to the side of the road. To go to the side of the road meant death. It was a firm rule of the transports: if you sat down on the roadside, you were declaring your intention to die. He sat on a boulder, took off his wooden shoes, and waited. An SS trooper guarding the march spotted him and walked towards him, his pistol ready. The Nazi seemed to study my father as he approached.

Their eyes met. The trooper glanced at my father’s shoes on the ground, then back to my father, and kept walking, moving right past my dad while holstering his pistol. My father was absolutely incredulous. It was supposed to be over for him! He was supposed to be dead!

The Nazi must have thought my father had a pebble in his shoe, or that he needed a break for a minute. Actually, my father had absolutely no idea what the man thought, because the unassailable rule was, if you went to the side of the road, you died. You didn’t get to take a pebble out of your shoe, or rub your feet, or take a break for a minute. But not for the first time in this difficult year a rule seemingly didn’t apply to my father. Once again, something went his way.

His heart racing, the shock of not being dead gave him a jolt that sprang him back onto his feet. Those few seconds sitting on the boulder regenerated just enough strength for him to stand and resume marching. But he was struggling to move now, lost in a fog. Soon the road pitched up steeply for a few hundred yards. At the end of the uphill, the route bent to the right and leveled off as my father and the other marchers reached a major intersection. From his left, from the south, thousands of soldiers and refugees were flowing north, away from the town of Steyr and towards Enns, directly across their path. The Mauthausen prisoners were heading west, cutting across the intersection and in front of the desperate refugees.

SS guards attempted to keep order in the dust-choked and chaotic crossroads, trying to shepherd their Jewish charges through gaps in the flow of soldiers on foot and horseback, and civilians with their luggage carts and children. Boiling like lava in a volcano ready to blow, the mass of civilians and soldiers agitated while the Jews filed slowly past them. Finally, the SS halted the marchers immediately behind my father. He was the last one into the junction.

View north up Weiner Strasse. This is the view refugees had while waiting in the intersection for the Mauthausen marchers, including my father, to pass on the street in front of them, from right to left. Just beyond the blue house in the distance are doors to homes - my father knocked on one of them. Source: Jack Hersch

My father stepped into the intersection moving like he was under water: slowly, exhausted from the steep uphill. Working his way across the crossroads he was alone, his steps agonizingly short, every breath a struggle for air. But watching him take step after ponderous step, he was simply too small and inconsequential for the refugees. Suddenly, their scramble away from the fighting could not wait another second. They went, plunging into the intersection before my father could get through. In a second, he was drowning in a streaming lava flow of Austrian townspeople and German soldiers. They hit him like a tidal wave, nearly knocking him over, refugees crossing in front and behind him, from his left to his right. Nearly panicked at first, with adrenalin flooding him his clarity suddenly became total. He could see his fellow marchers, and knew if he kept going, he would eventually reach them.

Or, if he turned quickly, he would be swept up and carried along with the refugees. He thought about it for an instant. Then he turned, joining the refugee column. No one noticed, or if they did, no one said anything. It wasn’t lost on my father that he was wearing concentration camp prison clothes. But two steps after turning he spied a raincoat on the ground. Picking it up in stride and throwing it on, it fit perfectly.

He was free. The Nazi troopers monitoring the march never saw my father’s snap maneuver. He heard someone call his name, a fellow prisoner, judging by the accent. He ignored it. He was not about to turn around. He didn’t dare do anything but walk straight ahead.

My father’s heart was booming in his chest. With his Mauthausen prison uniform invisible beneath the raincoat, he blended in. Even his hair didn’t give him away. The Nazis shaved a line down the middle of every Mauthausen prisoner’s head, a reverse Mohawk. But my father’s head hadn’t been shaved in weeks, and his hair had grown in enough so that the line in the center was no longer noticeable. He looked like any other refugee fleeing the fighting.

He was moving on some burst of energy that thirty seconds earlier hadn’t existed, and now he could feel that energy waning quickly. He didn’t have much stamina left. He took stock. The intersection was big and busy and had no houses facing it. Structures on either side offered no doors to knock on. But he could see ahead that the street narrowed. Its walls bore the doors and windows of small homes behind them. He scooted to the side of the street and approached one of the doors.

He wasn’t sure what to do. Knock. Don’t knock and keep going. He was so tired and hungry, he couldn’t go on much further. But it was very dangerous to knock. The person on the other side of the door might be a lifelong Nazi and shoot him dead, or hold him until the SS came to kill him. Or the person might be sympathetic. He knocked.

An elderly woman with white hair opened the door. My father spoke to her in fluent German, which he’d learned in Mauthausen by knowing Yiddish – a very close cousin to German and the language his family spoke at home – and honing it with SS guards and German prisoners. He told her he was hungry and asked if she would please give him something to eat. She studied him, her eyes taking in his raincoat, and then she stepped back from the door. My father walked in.

Letting him into her tidy home, she didn’t ask him where he’d come from, and my father couldn’t tell if she knew – or suspected – that he was from Mauthausen. Businesslike, or perhaps just formal, she directed him to sit down. My father never said where he sat, whether in the kitchen or the living room or somewhere else. She brought him a plate of cheese and noodles, then left him alone as he ate slowly, enjoying every bite.

When he finished, he felt truly full for the first time in a very long time. His face glowed. She allowed him to rest on the grass in her postage-stamp sized back yard. But after ten or fifteen minutes, she returned, nervous and agitated, and asked my father to leave.

Hearing the edge in her voice, my father assumed she suddenly comprehended the risk she’d taken by letting him in to her house. Maybe she’d spotted the Jewish star on his prison shirt peeking out from under the raincoat. Or perhaps his striped pants were enough to convince her she’d made a mistake. It could even be she feared a neighbor, or a refugee on the street, had seen her letting him in. She could be shot for it.

My father decided to wait just a few more minutes. The grass felt so good, and the meal settling in his stomach was his first decent food in a year. It was a few minutes too many. Two young SS troopers were patrolling on the street. They belonged to an SS company quartered in Enns. Flagging them down, the old woman brought them into her back yard. My father had no idea what she’d said to them.

The SS soldiers sprinted towards my father, rifles ready. He stood to face them. He was trapped. The worst possible outcome was playing out. Things were out of his control. He knew his future, if he had any, was up to these two kids – he guessed they were seventeen while he was now nearing nineteen – with SS lightning bolts on their tunic collars and loaded weapons in their hands. But as he watched them approach, he was at peace. What were they going to do, kill him? He figured he should have been dead months ago.

Amazingly, the SS troopers were Hungarian. They were among the thousands of young men from occupied countries who’d volunteered to serve in elite German units. One of them asked him, in bad German, "Who are you?" They had their big rifles pointed at his chest. He stood up as tall as he could make himself, looked right at them, and said in Yiddish, "I am a Jew from Mauthausen." They never realized he was mocking them.

Momentarily flustered by his brazenness, the Nazis took a step back to discuss what to do. Speaking his native language, my father understood everything as they debated if they should kill him in the old woman’s back yard, kill him in the street, or take him to the Enns gendarmerie headquarters, essentially the local police station. They acted as if they didn’t realize their captive understood them. Maybe they hadn’t seen the ‘U’ for Ungarn on his prison shirt under the raincoat, the letter preceding his prisoner identification number signifying he was originally from Hungary. Or maybe they didn’t know what it meant.

Eventually they decided, for no reason my father could discern, to take him to the gendarmerie station in the town square a half-mile away. They pushed him out of the woman’s yard, through her small house, and into the street, where they turned towards the square. Walking in front of the SS men, my father had time to contemplate what had just happened, and his earlier resignation was quickly replaced by frustration at what he judged to be his own monumental stupidity. He chastised himself for knocking on her door, for not having the sense to stay with the refugee column a little while longer, and for dawdling when she’d asked him to leave.

Soon my father and his SS captors arrived at the gendarmerie outpost in the town square. In many European countries, gendarmeries are nation-wide paramilitary organizations. The closest American version is a state police, or a sheriff serving rural areas. The Austrian Gendarmerie was the country’s national police force before the Nazi occupation. After Germany annexed Austria in 1938, the Gendarmerie was rolled into the Ordnungspolizei, or Orpo, the German national police during the Nazi reign. Under the Orpo, members of the Austrian Gendarmerie retained their jobs and responsibilities, as well as their ranks as gendarmes. My father was about to meet one of them.

Gendarmerie station. The brown building, today a cafe, housed the gendarmerie station where the SS troopers brought my father after his escape in April 1945. The door under the blue "Volksbank" flag was the main entrance to the Gendarmerie. Source: Jack Hersch

Dad and his escorts marched into the gendarmerie station. The lone gendarme inside, resplendent in his green Ordnungspolizei uniform, stood to attention behind his desk. The Nazis saluted and announced their prisoner. Returning the salute, the gendarme looked them over patiently and with great interest. My father immediately sensed this was not going to play out the way the young storm troopers had expected.

The gendarme said to the boys, "I’ll handle the prisoner." He said it with authority. One of the troopers replied, "Are you going to kill him?" "Don’t you worry," the gendarme said. "You leave him with me," and he ordered the SS boys to leave.

Hesitating for an instant, they eventually heil-Hitlered, smartly about-faced, and left. His authority over them emanated from Heinrich Himmler. As the high ranking Nazi controlled both the Orpo and the SS, the ranks of both were equivalent. Still standing by his desk, the gendarme said slowly in German, "I won’t hurt you," to which my father replied "danke," thank you, and then added, "ich spreche ein bisschen Deutsch." I speak a little German.

The gendarme smiled at that, then asked my father how it happened that he’d arrived at his headquarters. My father related to the gendarme the story of his escape and capture. The sense of peace he’d felt when the SS men had seized him in the old woman’s home had returned. Not only that, he felt surprisingly safe.

His instinct was right. When he’d finished with his story, the gendarme told my father he would put him in one of his jail cells for the night, feed him dinner and breakfast the next morning, and then he would get him safely back to Mauthausen.

And that’s exactly what he did. Dinner was a plate of eggs, my father’s first since the cattle car to Auschwitz nearly one year earlier. Breakfast was a roll and real butter, a rare delicacy in war-ravaged Europe. While giving him breakfast the gendarme told my father he would recall the same two SS soldiers who’d captured him, order them to return him to Mauthausen, and see that he’s accepted back.

I’ve known my father’s story of survival most of my life. It’s a story he often told, sometimes at the dinner table, other times when asked. But one thing he never said, and I never asked, was why the gendarme treated him so well. My father was an escaped prisoner from the notorious concentration camp seven miles away, and perhaps worse, he was Jewish. What made the gendarme deal with my father as kindly as he did?

My father never suggested a reason other than he was a good man, and there’s no doubt that’s true. But I suspect I know a second reason. My father’s father – my grandfather – had been a corporal of cavalry in World War I fighting for Austria, more accurately for the old Austro-Hungarian Empire, for the gendarme’s country. I often wonder if my father told the gendarme about his father’s cavalry service. With all the military-age men off fighting, it’s probable the gendarme was in his fifties or even sixties. He almost certainly was in uniform in the Great War. Maybe he felt the son of a man who’d honorably served the Empire deserved just treatment. It just might explain his actions.

After breakfast the following morning, the Austrian gendarme retrieved the two young Hungarian SS troopers. Making sure my father heard him clearly, he ordered the SS soldiers to return him to KZ Mauthausen. My father listened but doubted he would make it back alive, sure they would kill him the second they had the chance, and report that he’d tried to run away again. Besides, my father doubted he had the strength to walk a mile, let alone all the way to the concentration camp, in spite of the food he’d eaten and the rest he’d gotten in the past twenty four hours.

My father was wrong. With his hands tied behind his back, hiking seven exhausting miles over the Danube and up the hill they arrived at Mauthausen’s imposing main gate. Just outside the gate, the SS men untied my father’s hands and left him standing there, while they marched off back down the hill. The huge main double doors swung open, and my father walked through alone. He looked up at the Nazi guards in the towers. They returned his gaze impassively. Not surprisingly, or perhaps very surprisingly, they didn’t greet him. In fact, no one greeted him. No one sent him to the camp prison, or to the gas chamber. Maybe the gendarme had called ahead, or maybe the young SS men had said something that had given my father safe passage.

Main Gate: Mauthuasen Concentration Camp main gate, and barracks and the appelplatz, the main parade ground, as it looks today. Source: Jack Hersch

My father returned to the barracks and bunk he had been using before going on the death march the day before. He had been gone barely a day. His friends in the camp were stunned by his return. He told a few of them the story, but not everyone believed him. So he stopped telling the other prisoners where he’d been.

Definitielijst

- cavalry

- Originally the designation for mounted troops. During World War 2 the term was used for armoured units. Main tasks are reconnaissance, attack and support of infantry.

- Concentration Camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Holocaust

- Term for the destruction of European Jewry by the Nazis. Holokauston is the Greek term for a completely burnt sacrifice.

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- Jewish star

- Star of David on a yellow background which had to be worn by Jews in Nazi Germany and occupied territory during World War 2.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Mauthausen

- Place in Austria where the Nazi’s established a concentration camp from 1938 to 1945.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- trooper

- Short for paratrooper.

Information

- Article by:

- Jack Hersch

- Published on:

- 07-09-2019

- Last edit on:

- 21-11-2023

- Feedback?

- Send it!