Prologue

During the British bombing of the floating concentration camps Cap Arcona and Thielbek on 3 May 1945, more than 7,000 people died. That disaster in the Bay of Lübeck took place during the very last phase of the Second World War in Europe. The extremely violent death struggle of the Nazi regime was a complete chaos of German rear-guard battles, Allied bombardments, and senseless displacements of tens of thousands of concentration camp prisoners.

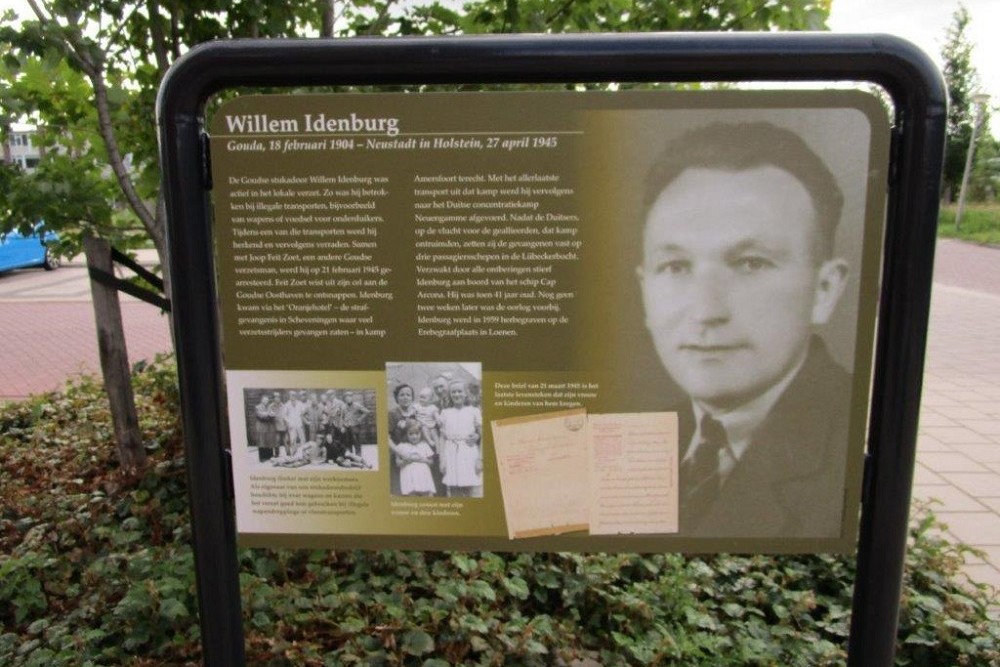

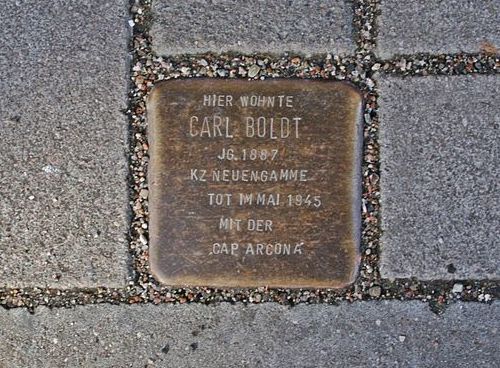

In October 1944, all concentration camp commanders met in the office of the SS-Wirtschafts- und Verwaltungshaupamt (SS-WVHA) [SS Economic and Administrative Office] in Berlin to discuss the liquidation of the camps. This was to prevent the advancing Allies from finding out about the horrific crimes the Nazi regime committed in the camps. In February 1945, the Western Allies were approaching the Neuengamme concentration camp near Hamburg. Starting in the beginning of March, the Higher SS-and Police Commander in Hamburg, Georg-Henning Graf von Bassewitz-Behr, and the Gauleiter of Hamburg, Karl Kaufmann, held their first discussions on the evacuation of Neuengamme and its ancillary camps.

The Higher Commander of the SS and Police and Kaufmann in his function as national defence commissioner of Hamburg agreed that the ancillary camps should be evacuated and the prisoners transferred to main camp Neuengamme. This transfer of prisoners was completed on 5 April 1945. Gauleiter Kaufmann then convinced Von Bassewitz-Behr to evacuate Neuengamme and to put the prisoners onto ships. Kaufmann could arrange these ships because he was also the Imperial Commissioner for German Maritime Navigation [Reichskommissar für Deutsche Seeschifffahrt (ReikoSee)]. He did not want the prisoners in Hamburg after the evacuation of Neuengamme, because he was afraid that they would plunder the city on the Elbe after the foreseeable liberation. Von Bassewitz-Behr agreed and charged the camp commander of Neuengamme, SS Leader Max Pauly, with the transport of prisoners. Pauly, in turn, entrusted SS Commander Christoph-Heinz Gehrig, who was the head of the camp administration, with loading the prisoners onto the ships.

On 19 April 1945, the British were so close to the Neuengamme main camp that the Nazis also had to evacuate this location. The transports of 9,000 to 10,000 prisoners from Neuengamme to Lübeck, partly by freight train and partly on foot, started in the third week of April. Those prisoners who were no longer able to travel due to exhaustion or illness were mercilessly shot in the neck by the accompanying SS and camp guards. Under appalling conditions, without sanitary facilities and deprived of food and drink, the remaining prisoners were placed on the cargo ships Thielbek (2,600 prisoners), Athen (2,300 prisoners), Otterbek, and Elmenhorst, and in freight train cars on the dock. Many prisoners died of malnutrition, dehydration and diseases such as typhoid fever and dysentery. From April 26, thousands of prisoners were taken to the ocean steamer Cap Arcona, which together with the smaller cargo ships, Thielbek and Athen, was anchored in the Bay of Lübeck. The ocean liner Deutschland was waiting in the same area for prisoners from Sachsenhausen.

On 1 May 1945, the British 11th Armoured Division was just outside the city of Lübeck. In the meantime, the Bay of Lübeck was filled with all kinds of German warships. On 3 May, the Cap Arcona, the Thielbek, and the Deutschland were situated among the numerous military ships and as a result were not recognizable as floating concentration camps. That same morning the British were informed by a representative of the Red Cross about the presence of the prisoners on board some ships. This had also been reported to them a few days earlier by Red Cross workers. However, the British assumed that there were German soldiers on board who wanted to escape to Denmark or Norway to continue the war, and they therefore ordered the ships to be attacked.

The Athen was taken back to Neustadt, which was located on the north side of the Bay of Lübeck. The prisoners that were on board were the lucky ones who escaped the British air raid. They were liberated that same day by British ground troops. Only a few hundred of the approximately 7,000 prisoners on the Cap Arcona and the Thielbek survived the disaster in the Bay of Lübeck.

Definitielijst

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Division

- Military unit, usually consisting of one upto four regiments and usually making up a corps. In theory a division consists of 10,000 to 20,000 men.

- Gauleiter

- Leader and representative of the NSDAP of a Gau.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

- Reichskommissar

- Title of amongst others Arthur Seyss-Inquart, the highest representative of the German authority during the occupation of The Netherlands.

Images

The burning ocean liner Cap Arcona in the Bay of Lübeck. Source: Vriendenkring Neuengamme.

The burning ocean liner Cap Arcona in the Bay of Lübeck. Source: Vriendenkring Neuengamme. Concentration camp Neuengamme. Source: Getuigen.

Concentration camp Neuengamme. Source: Getuigen. Rear entrance of Neuengamme Source: Vriendenkring Neuengamme.

Rear entrance of Neuengamme Source: Vriendenkring Neuengamme. Victim of one of the evacuations of the Neuengamme side. Source: Getuigen.

Victim of one of the evacuations of the Neuengamme side. Source: Getuigen.The Cap Arcona

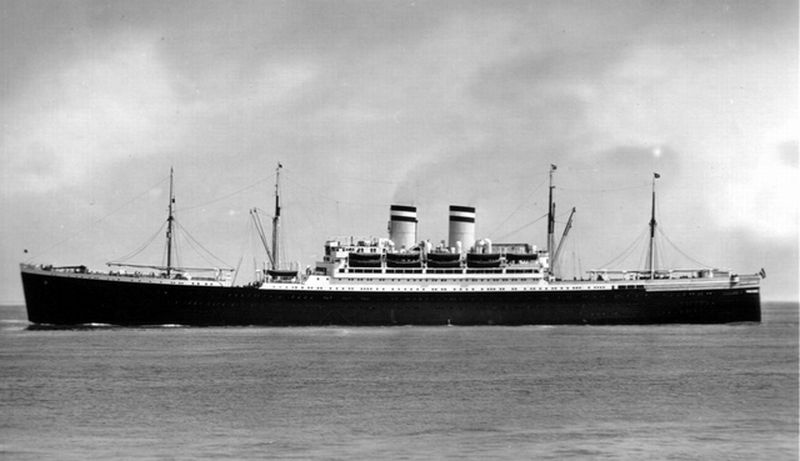

The Cap Arcona was a luxury passenger ocean liner of the Hamburg-South American Steamship Company. Weighing over 27,000 tons, the ship was built at Blohm & Voss in Hamburg and provided scheduled services between 1927 and 1939. Voyages were mainly between Hamburg and South America, especially Rio de Janeiro (Brazil) and Buenos Aires (Argentina). The Cap Arcona was one of the most beautiful ships of its time with a huge cherry wood hall, beautiful dining rooms, and luxurious cabins with excellent beds and washbasins for 1,365 passengers. At the outbreak of the Second World War, the ship was requisitioned by the navy and deployed for troop transport. From 29 November 1940, the ship in Gothenhafen, today's Polish town of Gdynia, was deployed to provide accommodations for 2,000 seamen who were trained as crews for U-boats. In April 1941, the engine room was severely damaged by a fire. By the end of 1944, Soviet troops were so close to the eastern border of Germany that the Germans proceeded with large-scale evacuations of troops and civilian refugees from East Prussia to north-western Germany. For this reason, the Cap Arcona was made ready to sail again. From 31 January to 4 February 1945, the passenger ship took 10,000 refugees from Gotenhafen to Neustadt at the Bay of Lübeck, and from 5 April the Cap Arcona took the same number of evacuees to Copenhagen in Denmark. However, due to fuel shortages, the ship was unable to make a third voyage. Captain Heinrich Bertram was therefore ordered to sail to Neustadt. On 14 April, the Cap Arcona eventually anchored in the Bay of Lübeck.

On 15 April, Gauleiter & ReikoSee Kaufmann from Hamburg gave an order by telephone to Counter Admiral Conrad Engelhardt, Seetransportchef der Wehrmacht in Flensburg, that the Cap Arcona had to take on board 8,000 concentration camp prisoners from Neuengamme. Because Engelhardt refused, the Cap Arcona was placed under the direct command of Kaufmann. On 20 April, Captain Fritz Nobmann of the Athen tried to off-load the prisoners on his cargo ship onto the Cap Arcona, but Captain Bertram refused because of the risks and the insufficient capacity of his ship. The next day, the Captain of the Athen made a new attempt to put Athen prisoners on the Cap Arcona. This was again refused by Bertram, this time with the consent of his shipping company, Hamburg-Süd, to which the ship now belonged. On 23 April, Kaufmann ordered director Dittmer of that shipping company to take prisoners aboard the Cap Arcona, but two days later Captain Bertram still refused while the Athen now lay alongside the ocean liner. That night a courier picked up a written order from Dittmer for Bertram. The next day this order was handed over to Bertram by SS-Commander Gehrig, who was accompanied by an SS-Executive command. Moreover, Gehrig threatened Bertram with death; so the merchant captain agreed to board the prisoners. However, he refused to take full responsibility for what might happen to his ship and to the people on board.

From 26 April 1945, 6,500 prisoners from the Athen itself, the Otterbek, the Elmenhorst, and from the freight train cars were taken by the Athen to the Cap Arcona. The other prisoners remained on the Thielbek. On board the Cap Arcona the prisoners were grouped by nationality. The Russians were locked up in the banana bunker and the potato cellar without light or ventilation. The German prisoners mainly ended up in the luxury huts on C-Deck, the French in the barges, and the remaining prisoners, at times in groups of up to 12 people, in the mostly double and quadruple cabins. The large numbers of seriously ill prisoners were housed in the huts on D-Deck. On average, every half hour a death occurred on board the passenger ship. The dead were brought ashore to Neustadt on a daily basis by a funeral command with a motorboat and buried in mass graves at the local cemeteries. The 50 SS and the 500 naval artillery soldiers, who guarded the prisoners, stayed in the restaurant and the main hall on the upper deck. On 30 April, the Athen took back 2,000 prisoners from the Cap Arcona.

In the early morning of 3 May, a supply cutter came alongside the Cap Arcona to deliver drinking water. It remained docked next to the ship. A little later there was, via Neustadt, another transport of 205 prisoners from Mittelbau-Dora, an ancillary camp of Buchenwald, who had to board the passenger ship. They were housed in the luggage compartment. That same morning the Cap Arcona and the unoccupied passenger ship Deutschland, were supplied with a small amount of fuel oil by the tanker Forbach. From the 1st of May, the Deutschland, a passenger ship of the Hamburg-American Packaging Company (Packetfahrt-Actien-Gesellschaft - HAPAG) weighing over 22,000 tons, was anchored in the Bay of Lübeck near Sierksdorf, south of Neustadt. The intention was to place prisoners from Sachsenhausen concentration camp on this ocean liner.

Definitielijst

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Gauleiter

- Leader and representative of the NSDAP of a Gau.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Images

The Cap Arcona in 1927. Source: Wikipedia.

The Cap Arcona in 1927. Source: Wikipedia. The ocean liner Cap Arcona. Source: Shipsnostalgia.

The ocean liner Cap Arcona. Source: Shipsnostalgia. HAPAG `s ocean liner Deutschland. Source: Shipsnostalgia.

HAPAG `s ocean liner Deutschland. Source: Shipsnostalgia. The Deutschland before the Second World War. Source: Wikipedia.

The Deutschland before the Second World War. Source: Wikipedia.The Athen and the Thielbek

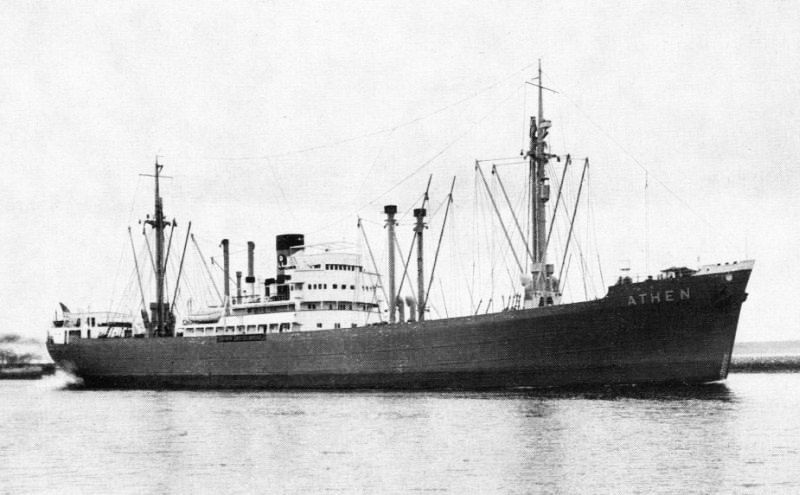

The Athen

The Athen was a 4,450-ton cargo ship of the Deutsche Levante Line, which was delivered in 1936 by the German shipyard in Hamburg. The ship was in use from 1940 by the mine warfare command and control department of the navy, but in 1942 the cargo ship was returned to its original owner. In mid-April 1945, the ship was commissioned by Gauleiter & ReikoSee Kaufmann to take in concentration camp prisoners from Neuengamme. On 19 April, the Athen was directed to the industrial harbour of Lübeck. That same evening Captain Nobmann was visited by SS-Commander Gehrig, who ordered him to take 2,000 prisoners on board. The next day 2,300 prisoners and 280 SS guards were boarded. Until 26 April, Captain Nobmann made several trips to give the prisoners to the Cap Arcona. On that day, the Athen sailed twice back and forth between Lübeck and the Cap Arcona, which was anchored at Neustadt, transferring a total of 6,500 prisoners.

The following days were used to clean the compartments of the cargo ship as much as possible using fire hoses. On 30 April, the Athen once more had to take over 2,000 prisoners from the Cap Arcona because the Germans thought the luxury passenger ship was too crowded and were afraid of not being able to maintain overall control. The cargo ship was then anchored in the Bay of Lübeck, at Neustadt. A Dutch survivor recounted that "the medical care was appalling. Practically nothing was being done about the dysentery sufferers. Only the worst cases of inflammation are treated, after which they are swathed in bandages of toilet paper. We suffered a lot from the cold and were constantly coughing. Reason being that the surroundings consisted entirely of iron; no matter where you lie. We have no choice but to sleep on our backs, because our hips were raw. The days on the Athen were like a horror in our memory."

On 3 May at 12:30 p.m., Captain Nobmann was ordered by the commander of the naval base in Neustadt, Heinrich Schmidt, to enter the port for the purpose of taking more prisoners on board. He immediately weighed anchor and entered the harbour. At 1:45 p.m. the ship was moored at the local naval port.

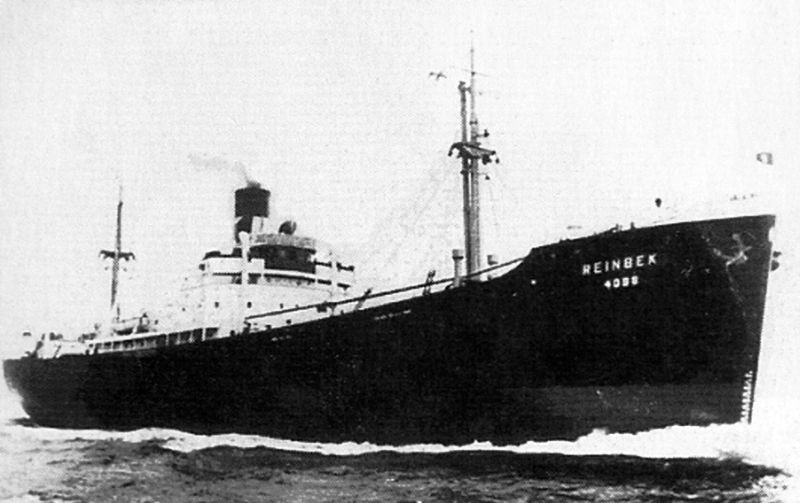

The Thielbek

The Thielbek was a fairly new cargo ship of 2,815 tons, which was delivered in 1940 by Orenstein & Koppel AG at Lübeck. The cargo ship was damaged in 1944 on the Elbe by a British air raid and was repaired by a ship repair company located in a shipyard at the Bay of Lübeck. Although the repairs had not yet been completed, Gauleiter Kaufmann had the ship towed to the industrial harbour of Lübeck on 19 April 1945. Captain John Jacobsen and 18 crew members were on board. From 20 April, more than 2,000 prisoners were taken on board, who were locked up in the compartments without food or drink or sanitary facilities. A small group of SS and a group of naval artillerymen came on board as guards. The last loading of the Thielbek consisted of coal. As a result, the compartments were extremely dirty. The weakened prisoners were tightly packed on the steel plates of the cargo compartments. In the lower front cargo compartment were the sick, of whom dozens died daily.

Part of a letter from Captain John Jacobsen to his wife has been preserved. He describes how he found his ship after the prisoners were brought on board during his absence. He had to cross the Elmenhorst to get on board. "There are four corpses on the Thielbek. Prisoners are constantly dying. Every morning the dead are first removed from the compartments. Five deaths this morning on the Thielbek. They are now being collected. You can see who will perish tomorrow. Yet, not all of them are half-starved bodies, on the contrary, there are also some who still look good, powerful and fresh. The crimes for which they were imprisoned also differ considerably. Ages range from 14 to 70 years. All social classes are represented. There are also all kinds of nationalities. The foreigners are not allowed to enter the deck. They sit like sardines on top of each other. They did their needs in private barrels, which are emptied if necessary. At first, you see all this with horrified eyes. However, you quickly get used to it. Tragically, people are not grasping their situation. The guard consists of soldiers, but the prisoners keep their own order and discipline. The distribution of food is also in the hands of prisoners, who share bread, packets of margarine along with pencils and papers. If only there was more hygiene. On the hatches where dead corpses or private barrels were placed, loaves of bread are stored and divided. Maybe they are well-disposed because they see the end approaching and with it, freedom and probably revenge as well. Nevertheless, I will be glad if I don't have to see this situation anymore. After all, it is one big misery and unworthy of humanity". Probably the wife of Captain Jacobsen was spared the overly horrible images, as the testimonies of several imprisoned survivors accounts of a true hell aboard the Thielbek.

On 1 May 1945 the Thielbek was loaded with supplies, but the ship remained in the harbour. The next day at 12:00 the last transport, which arrived on foot from Neuengamme in Lübeck, was boarded on the cargo ship. Two hours later the Thielbek was towed out of the harbour by two tugboats and then towed down the Trave in the direction of the Bay of Lübeck. The German ship anchored 700 meters from the Cap Arcona with about 2,800 prisoners on board.

Definitielijst

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Gauleiter

- Leader and representative of the NSDAP of a Gau.

- mid

- Military intelligence service.

- mine

- An object filled with explosives, equipped with detonator which is activated by either remote control or by colliding with the targeted object. Mines are intended to destroy of damage vehicles, aircrafts or vessels, or to injure, kill or otherwise putting staff out of action. It is also possible to deny enemy access of a specific area by laying mines.

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

Images

The Athen of the Deutsche Levante Line. Source: Shipsnostalgia.

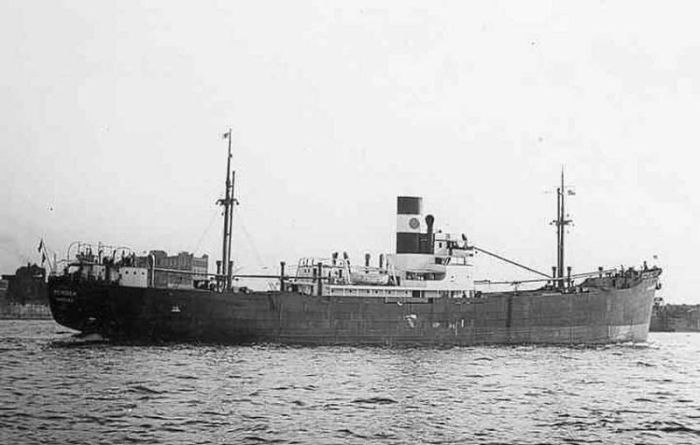

The Athen of the Deutsche Levante Line. Source: Shipsnostalgia. The cargo ship Thielbek. Source: Shipsnostalgia.

The cargo ship Thielbek. Source: Shipsnostalgia. The Thielbek was salvaged after the war and brought back into service as Rheinbek. Source: Getuigen.

The Thielbek was salvaged after the war and brought back into service as Rheinbek. Source: Getuigen.The Swedish Red Cross

The Swedish Red Cross played an important role during the months of April and May 1945 in the relocation of tens of thousands of concentration camp prisoners. The prisoners had been dependent on this organisation for months for their food supply. The Red Cross packages, which were regularly supplied by cargo ships, not only contained food, but also cigarettes and sometimes medicines. The Swedish Red Cross was also active in other ways. For example, on 20 April 1945 a total of 4,255 Danish and Norwegian concentration camp prisoners were taken by the legendary white buses via Denmark to Malmö in Sweden.

On 29 April, Doctor Hans Arnoldson, representative of the Swedish Red Cross in Lübeck, received an anonymous letter describing the terrible situation of the prisoners on the ships in the port of Lübeck. He then offered the German authorities to take 250 sick French, Belgian and Dutch prisoners to Sweden on board the cargo ships Lillie-Matthiessen and Magdalena. The ships had brought a load of Red Cross packages and were therefore readily available. The Germans agreed and the next day a total of 250 prisoners were taken from the Thielbek and the Cap Arcona. That same day the Lillie-Matthiessen departed for Trelleborg in Sweden carrying 420 female prisoners from concentration camp Ravensbrück, and the Magdalena with the same destination carried approximately 400 male prisoners from the Thielbek and Cap Arcona and the sick from a barn in Süsel, a village 10 kilometres southwest of Neustadt.

On 2 May, Arnoldson began preparing for the transfer of the concentration camp prisoners, who were on the docksides and ships in Lübeck, as the British were quickly advancing. However, when he appeared on the dock that morning, it was empty and the ships were gone. The representative of the International Red Cross in Lübeck, P. de Blonay, informed the British General-Major George Roberts of the 11th Armoured Division about the prisoners aboard the ships in the Bay of Lübeck near Neustadt. Roberts passed this information on to the headquarters of Group 83 of the 2nd Tactical Air Force (TAF). On the morning of 3 May, Arnoldson told the British that there were prisoners on the ships in the Bay of Lübeck. In the event of a possible air attack on the ships, they would be at great risk. That same afternoon, Arnoldson accurately informed two British officers about the prisoners. The officers promised to act immediately, but it was already too late to prevent the imminent catastrophe.

Definitielijst

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Division

- Military unit, usually consisting of one upto four regiments and usually making up a corps. In theory a division consists of 10,000 to 20,000 men.

- International Red Cross

- Name of a complex of co-operating humanitarian organisations which primarily focusses on providing assistance to the sick and wounded military during wartime, to prisoner of war and to civilians during wartime and other conflicts. The role of the Red Cross during World War 2 is somewhat controversial.

Images

The air raid

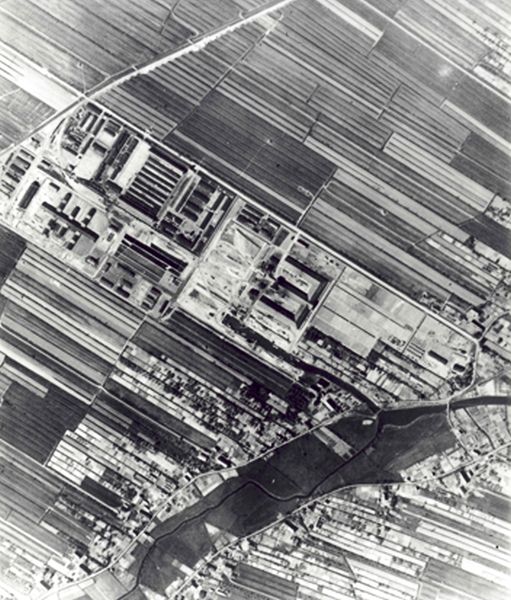

In April 1945, the British advance in north-western Germany was unstoppable. On 15 April, the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp was handed over to the British by the Wehrmacht. Two days later, British planes dropped leaflets over Neuengamme with an aerial photograph of the camp and together with this indicating that they were aware of the camp's and prisoners existence. On 19 April, British troops reached the left bank of the Elbe at Lauenburg, about 30 kilometres from Neuengamme. On 26 April the British took Bremen. Two days later they made a breakthrough at Lauenburg and established a first bridgehead in Schleswig-Holstein. The next day, fierce German resistance slowed down the British advance in the Lauenburg area. As a result, the British also expected heavy resistance in the areas still controlled by the Germans. That is why military measures were taken, including armed reconnaissance flights by tactical air units. On 30 April, the British troops approached the coast at Lübeck and Travemünde, and the next day the 11th British Armoured Division stood just outside the city of Lübeck. In the afternoon of 2 May, they took the city without battle.

That same afternoon British reconnaissance aircraft discovered that in the Bay of Lübeck, near Neustadt, six German destroyers, some U-boats and troopships had arrived. The Cap Arcona and the Thielbek lay in among the warships and could not be recognized as floating concentration camps. The ships did not fly a white flag, had armaments on board, and on deck armed guards were walking around. Most SS men had meanwhile secretly left the ships. The still empty Deutschland was also anchored among the German military ships.

On 3 May, at 11:15 am, a day order 71 was issued by the British RAF headquarters. German ships that left or threatened to leave the ports of Schleswig Holstein on a large scale had to be destroyed by Groups 83 and 84 of the 2nd Tactical Air Force (TAF). Twenty minutes later, the first squadrons of Hawker Typhoon Mark 1B fighter-bombers took off from the Ahlhorn base to target the ships in the Bay of Lübeck. However, they returned shortly afterwards to their original position due to poor visibility. At 11:45 four Typhoons took off from the Hustedt base. They fired 32 60lb RP-3 rockets on the Deutschland, of which only four hit their target. The damage to the ocean liner was minor and the fires that occurred could easily be extinguished by the crew.

At 14:00 hours, the second air attack started with nine Typhoons from the base Plantlünne near Nordhorn. Half an hour later, five aircraft fired 40 rockets at the Cap Arcona, after which the ship was engulfed in flames. Captain Bertram had white flags hoisted but the damage had already been done. The wood used to decorate the luxury ship and the thousands of concentration camp prisoners were easy prey for the fire. The stairwells worked like chimneys, further fuelling the fire. Life jackets were only for the crew and the guards, so that many prisoners who could get off the ship drowned in the cold water of the Bay of Lübeck. The lifeboats could not be lowered because the ropes were incinerated by the fire. Some of the boats that were launched in one way or another, were quickly overloaded and sank. The few remaining SS men and guards shot their weapons at fleeing prisoners, then jumped overboard or were trampled in panic by the crowd. The supply cutter, which was still alongside the Cap Arcona, quickly took a number of shipwrecked people and then sailed to the naval port in Neustadt, which saved the lives of some 50 prisoners.

At the same time as the Cap Arcona, the Thielbek was attacked by four Typhoons which fired 32 rockets at the packed cargo ship, after which the attack was continued with firing of the 20mm on-board machine guns. The ship quickly capsized, while black plumes of smoke rose from it. The Thielbek sank fifteen minutes after the attack. Captain Jacobsen, his first officer, ten other crew members, and almost all 2,800 prisoners went down with the ship.

At 15:15, the third and fourth British air raids started with a total of seventeen Typhoons from the Ahlhorn and Celle base. With 36 rockets along with on-board weapons, these aircraft bombarded the Deutschland, which caused the ship to go up in flames. The crew was able to leave the ship safely by means of a couple of lifeboats. Moments later the burning passenger ship was hit again with two 500-pound bombs which were dropped by the Typhoons of base Celle. Four hours later the ship capsized and sank.

From the Athen, the British fighters were shot at with anti-aircraft guns. The cargo ship was in turn attacked by British tanks that had taken position at the Neustadt maneuvering area. After the Athen had been hit several times by shells from these tanks, the crew and the guards left the ship. The prisoners disembarked but stayed close to the dock where they got their food supply such as cheese, sugar and butter from a warehouse appropriately named "Glücksklee" (four-leaf clover). A few hours later the prisoners were freed by British ground troops.

The prisoners aboard the Cap Arcona were less fortunate. The on-board fire extinguishing equipment and the watertight bulkheads were not working. Most of the prisoners perished from burning, smoke inhalation, or drowning. The few who managed to reach the beach were attacked by SS, Wehrmacht soldiers, and members of the Hitler Youth. Hundreds of prisoners were killed in this way. Some rushed minesweepers, which had received strict orders to rescue only Germans. Prisoners who wanted to climb aboard these ships were beaten off or shot.

At 17:00 a fierce explosion took place on board the Cap Arcona, possibly caused by oil vapours in the fuel tanks, which were only filled to a few percent. The ship capsized, but remained partially above water because the water depth was only 18 meters, while the passenger ship was 26 meters wide. A few prisoners who had remained on board were able to survive on the warm hull of the ship. They were picked up in the evening by British rescue teams. Ultimately, approximately 350 prisoners of the Cap Arcona and no more than 50 prisoners of the Thielbek survived the disaster in the Bay of Lübeck.

Definitielijst

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Division

- Military unit, usually consisting of one upto four regiments and usually making up a corps. In theory a division consists of 10,000 to 20,000 men.

- RAF

- Royal Air Force. British air force

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Images

The British aerial photo of Neuengamme taken on April 16, 1945. Source: Vriendenkring Neuengamme.

The British aerial photo of Neuengamme taken on April 16, 1945. Source: Vriendenkring Neuengamme. A British Hawker Typhoon fighter-bomber. Source: Wikipedia.

A British Hawker Typhoon fighter-bomber. Source: Wikipedia. A Hawker Typhoon is loaded with rockets, july 1944. Source: Wikipedia.

A Hawker Typhoon is loaded with rockets, july 1944. Source: Wikipedia. The Cap Arcona on fire. Source: Geschiedenis 24.

The Cap Arcona on fire. Source: Geschiedenis 24. Cap Arcona capsized and still burning. Source: Vriendenkring Neuengamme.

Cap Arcona capsized and still burning. Source: Vriendenkring Neuengamme.Epilogue

After the disaster, corpses washed ashore for weeks onto the beaches in the Bay of Lübeck, from Timmendorf in the south to Pelzerhaken in the north. The last human remains were not found until 1971. With over 7,000 casualties, the massacre in the Bay of Lübeck became the biggest maritime disaster in history after the sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff on 30 January 1945. In that disaster, with three torpedoes a Soviet submarine sank the former German cruise and passenger ship, packed with German refugees. More than 9,000 people were killed. The harshest part of the disaster in the Bay of Lübeck is that it took place in the very last phase of the Second World War. Hitler had already committed suicide, and the Allies were about to overpower Germany. So why did the SS still go so far as to desperately try to keep the atrocities of some concentration camps secret while several others had already been liberated? Because the SS had left the ships prematurely, the fire extinguishing equipment on the Cap Arcona had been rendered unusable, and because the ships with prisoners on board had not been identified, it seems that Von Bassewitz-Behr, Kaufmann, and Pauly had speculated about a British attack. In any case, they seriously considered that such an attack could be carried out, and they subsequently took advantage of the situation to get rid of as many prisoners as possible. The shelling of the prisoners who were able to reach the beach seems to confirm this.

It is generally believed that despite the warnings of the Red Cross, the British allowed the attacks on the ships to continue because they did not want to run any risk of SS soldiers and military equipment escaping to Denmark or Norway, where the Germans could continue the fight. The British Government decided that the secret documents relating to the shelling of the floating concentration camps in the Bay of Lübeck would not be made public until 2045. This 100-year secrecy is seen by the survivors and their families as an indication that the British have something to hide. This seriously disrupts the processing of the disaster.

RAF pilot Allan Wyse of squadron 193 later recalled: "We used our cannon fire at the chaps in the water.....we shot them up with 20mm canons. Horrible thing, but we were told to do so and we did it. That`s war."

Definitielijst

- cannon

- Also known as gun. Often used to indicate different types of artillery.

- RAF

- Royal Air Force. British air force

- shelling

- Indication for shooting targets with grenades. Both from artillery and armoured artillery.

- squadron

- A military unit in the Belgian navy usually six to eight small ships operating together under one command. The smallest military unit in the Dutch air force of about 350 men. In most countries is the designation of a military unit thesize of a company. It is either an independent unit, such as a battery, or part of a bigger Calvary unit. In the air force it is the designation of a unit of aircrafts.

Images

Washed ashore, a victim of the disaster in the Bay of Lübeck. Source: Getuigen.

Washed ashore, a victim of the disaster in the Bay of Lübeck. Source: Getuigen. The wreck of the Thielbek. Source: Getuigen.

The wreck of the Thielbek. Source: Getuigen. The wreck of the Cap Arcona after the war. Source: Vriendenkring Neuengamme.

The wreck of the Cap Arcona after the war. Source: Vriendenkring Neuengamme. The Cap Arcona-Thielbek monument in Neustad, Holstein. Source: Vriendenkring Neuengamme.

The Cap Arcona-Thielbek monument in Neustad, Holstein. Source: Vriendenkring Neuengamme.Information

- Article by:

- Peter Kimenai

- Translated by:

- Fernando Lynch

- Published on:

- 11-12-2019

- Last edit on:

- 19-09-2024

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Related books

Sources

- DOBSON, C. e.a., De ondergang van de Wilhelm Gustloff, Elsevier, Amsterdam/Brussel, 1979.

- GEERTSEMA S., De ramp in de Lübeckerbocht, Boom, Amsterdam, 2011.

- MALLMANN-SHOWELL J.P., Das buch der deutschen kriegsmarine 1935-1945, Motorbuch verlag, Stuttgart, 1995.

- SCHUYF, J., Nederlanders in Neuengamme, Aprilis, Zwolle, 2005.