Preface

"‘If only I were dead’, I wished. Why? I’m tired of struggling to stay alive. I’m afraid to think about the future, because I have an ideal. Yes, did not do my homework and I’m afraid school will start again. That is why I don’t care anymore if I do not witness the liberation. Another liberation might be for me. A liberation from this world, where you put others down to rise higher or to stay alive. This world of self-interest. Nobody understands me and that makes me feel so discouraged."[1]

This quote is from the 16-year-old teenager F.J. Wijkhuizen from Delft. As a teenager in wartime he had a very difficult time dealing with the situation. This strongly affected him personally because, as is evident from his diary, he had no parents or friends who could help him with these feelings. The last month of war was not just a difficult period of time for Wijkhuizen, but also for Western-Netherlands. Writers of diaries from the four cities were already dealing with food shortages which were increasing every week. People were dependent on soup kitchens and on the Swedish and Swiss Red Cross which offered some help with bread and margarine supplies. Other than that, Western Netherlands was on its own. In addition, the course of the war played a significant role in the daily lives of the people. People were constantly trying to find out the location of the Allies and where they were going. Moreover, there was a small group of diarists who reflected on five years of occupation and who had a vision with which the Netherlands and a future international organisation should comply. Based on these three themes, the perception of the last month of the war will be researched.

The battle to stay alive

The first large theme that interested the diarists was hunger. Hunger remained a big issue among them despite the upcoming liberation. Mr. C.L.M. Kerkhoven, a 50-year-old professor from Voorburg, noticed this hunger standing in line at one of the soup kitchens. "To the I.K.B. kitchen at a quarter to eleven. If you are standing in line you will hear how much hardship there is, people look miserable but still have hope in their hearts that soon it will be over and that soon we will be freed."[2] Fie van Baaren, a 45-year-old housewife from Delft, described the hunger as follows: "It is hunger at home and I even ate the cat’s food; my brother has lost so much weight that he can’t walk any further than the garden and the kitchen. He can’t work for a while; his legs and jaws are so skinny, it is a terrible sight. . . We are all so tired of the war, not even the food, but the pressure is so high. Here in Holland it is awful; we are slowly starving."[3] The hunger got so bad that by the time the food supplies were almost empty, Rudolf Jacob Lodewijk Simons, a 40-year-old Jewish man hiding in The Hague with a falsified identity card, noted the following: "It is a normal phenomenon, that you see people cry in shops or on the street because somebody has taken their place or because they forgot their coupons."[4] From the 66 diarists, 46 observed that either they or the people around them were starving. They lived off a minimum share and were dependent on soup kitchens or the help of the Red Cross. Hunger controlled society in this last month and caused major disappointment and despair among the diarists.

People struggled with other problems related to hunger. Heat sources were no longer available, and gas, water and electricity were shut down. Cooking and keeping food warm became problematic, just like heating the dwelling. "The last days of April were primarily cold. As a result of fuel scarcity we had already stopped heating the house. Only if food had to be cooked and the ´gas heater´ was in use – with paper, finely chopped wood and coals – the temperature would rise a bit in the living room,"[5] states 45-year-old J.S. Bartstra, a former professor who was active in the resistance. The absence of heat sources resulted in not only hunger, but also an increasing number of illnesses and deaths. This too in Leiden: "In the afternoon we unexpectedly received the death notice of the 19-year-old daughter of Van Wijngaarden, the director of the Museum of Antiquities, which affected us deeply because even though Kees didn’t see W. at the museum for three days, he did not know of her illness. This is a huge loss for this family, especially because the mother is very malnourished."[6] Trudy Braat-Bertel, the 26-year-old wealthy housewife from Oegstgeest, realised that even affluent families were dying of starvation. Similarly wrote Han de Wilde, a 39-year-old from Leiden who was known for his mattress shop on the Breestraat: "It is like watching paint dry. The days flew by thanks to bakery inspections, digging, sowing and seeding in both my allotments, chopping wood and running errands (because cycling is highly dangerous; every day bicycles are being taken!), but life seemed dry, monotonous and hopeless."[7] The Dutch society weakened. People died of starvation and cold, people became weaker emotionally with every setback, and the days were endless.

All available wood was collected. Even the trees around the Hofvijver didn't make it. Source: Wikipedia/NIOD

Not everyone experienced this last month as desperate. There were families that possessed a reasonable food supply. Social relationships were also maintained. The family of Th. Witting, a 35-year-old stay-at-home dad from Ypenburg, celebrated Easter with a ‘good’ breakfast: "At half past seven, Mother, Jopie, Jantje and I went to the mass and took communion. Mother baked a cake. From the kitchen came beet soup. In the afternoon I played with the children and the Meccano box. Tonight we are eating porridge and soup."[8] Next to celebrating Easter, wedding anniversaries and birthdays, visiting each other and maintaining social relationships remained important. For example, Van Riemsdijk, the ex-marine from The Hague, wrote: "At two o’ clock in the afternoon, music was made in the home of Dr. Keiholz, together with Betsy and Mrs. Grelinger. Afterwards there was a wonderful get-together with tasty things. Including an abundance of delicious apple fritters, buns filled with smoked mackerel, radish, etc. Then a dinner that was excellent for this period of time! Cod, potatoes, lettuce (everything in abundance), sprinkled with a delicious Hungarian wine; then meat (roast beef), potatoes with escarole."[9] J.M.G. Beelen, too, an 18-year-old schoolgirl from Haarlem, kept doing sports at least once per week despite the hunger: "I am going to play tennis! Rietje Bonarius can’t go all of a sudden. Tonight I went to A. v.d. Ham and to L. Nieland. They both still go."[10] Next to tennis she still met with her friends occasionally. In total there were 13 diarists in the last war phase who had enough food thanks to supplies that were built up during the war. These people primarily came from wealthier circles and richer families.

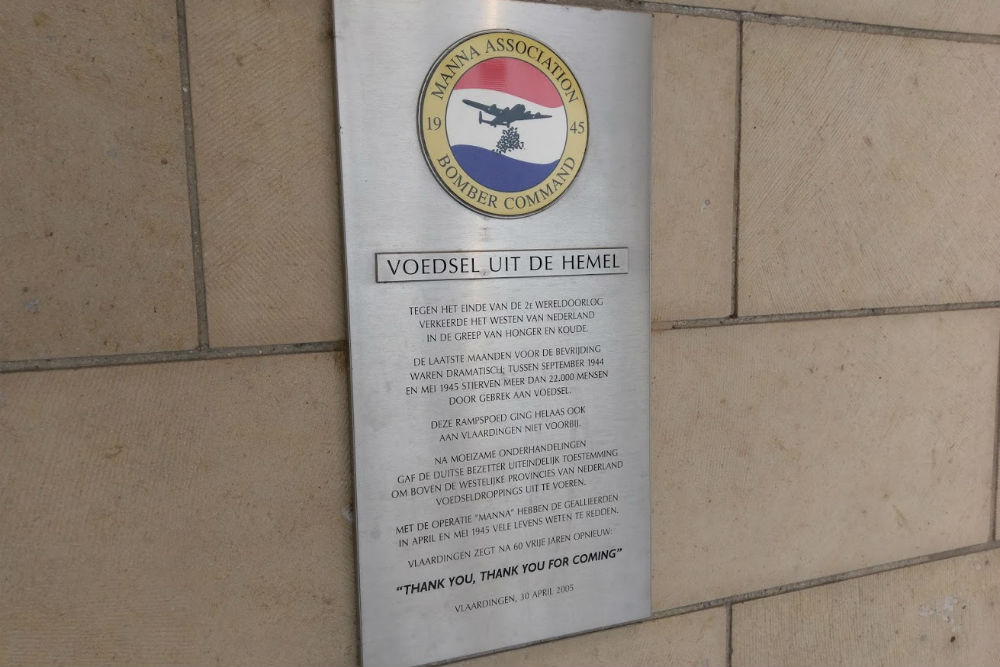

From the above it can be seen that in this last month, people not only experienced hunger and cold but also moments of joy. The biggest joyful moment among the diarists this month took place on April 29th, when food drops took place. J.H. Kasten, a 65-year-old technical civil servant from Leiden, summarised this nicely: "In the afternoon there was great joy when heavy bombers dropped food for the people at the airport of Valkenburg. A big excited crowd watched from the roofs and chimneys of the houses and from the tracks. It was an impressive sight. The need was high, but thank God rescue was near. Every hour we hope that the redeeming word peace will resound over the lowlands."[11] Mia Boeree, a teenage girl from Leiden who spent most of her time outside with friends, also wrote about the food drops in her diary: "got coffee with real milk at home with a meal and what a gift from English airplanes, big heavy bombers, that nobody took seriously if the packets did not really fall down at the airports near Valkenburg. It was like Mad Tuesday, the people climbed on the roofs, waved their handkerchiefs, cheered and the pilots greeted us back. Everyone had the feeling, the war has now ended, because that is not possible in total time of war!"[12] What makes this last part so special is that Mia finds that the war has ended for her, even though the war would end a week later. Five diarists realised that such help from the Allies could not have taken place earlier.

A.F. Koenraads, a 40-year-old teacher from Delft, interpreted this armada of airplanes differently: "Sceptics wonder what they will see on the table from all that has been dropped. They were not entirely wrong. That not everyone profits from it, that is not the worst thing. The worst thing is that, with such a gift from the sky, we need to be kept alive. I can’t shake the thought that the whole unleashed armada did not bring us one step closer to liberation, yes that they gave us food for a day at most.d I’d rather see paratroopers falling from the planes."[13] Also J.A. Ladan, a 30-year-old technical draughtsman from The Hague, noticed that the food drops were being criticised. "R.A.F. will drop packets of food. This subject is hotly debated! People call it madness."[14] They are the only diarists within the diary research who were negative about the food drops; the others were extremely excited. However, the food drops in Leiden and Haarlem didn’t go as planned. The mattress seller Han de Wilde from Leiden noted that some people were very selfish: "Unfortunately some people from Katwijk could not keep their hands to themselves and decided to rob by stealing cans or opening them. They were caught, took a good beating, stood with a sign around their necks saying ‘I am a thief’. Their names will be read out loud in church, which really means something to Katwijk people!"[15]

Food transport from Rhenen to Western-Netherlands. The army truck carries the white flag because the capitulation has not yet been signed. Source: Wikipedia/Nationaal Archief

Definitielijst

- heat

- High-explosive anti-tank warhead. Shaped charge projectile to punch through armour. Used in e.g. bazooka or in the Panzerfaust.

- Mia

- Missing in action, Missing.

- paratroopers

- Airborne Division. Military specialized in parachute landings.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

War news

A second important concern was the warfare and the uncertainty surrounding the liberation. The diaries showed that progress from the Allies brought a lot of joy. Early April, the 45-year-old welder L.D.J. Thannhäuser from Haarlem wrote about the approaching Allies: "At the moment we are all hopeful, the news from all fronts is more than good, in several places the Americans and the English have crossed the Rhine and this is very important for our country, especially for the part where we live, namely north of the big rivers. We have hope that we too will be liberated in a few weeks, and even if it will not be much! Perhaps slightly better than it is now."[16] Next to happiness and optimism among the people in Haarlem, again it appears that people were dealing with shortages. Positive war news sparked joy nonetheless. "Achterhoek practically liberated. Don’t know much else, but can tell from the newspaper that it is going great!"[17], states the 40-year-old civil servant C.D.M. van Erp Taalman-Kip from The Hague. News from the front would put 38 diarists in a good mood whenever they would hear similar news. Other diarists did not describe their reaction or were reticent.

An unemployed man from Wassenaar, the 40-year-old Johan L. van Soest, described his feelings in a different way: "Was among Germans on Easter! April 1st, Easter Sunday, the front moves, it is even starting in the east of the country; on Easter Monday stronger and stronger. But here!? Many Germans have left, but the Ostkommandatur is still occupied, the guard at the telephone exchange still present… Joy about the front messages, wretchedness that there is nothing here yet. Beautiful spring weather, then cold and rainy. Good meals, then a hollow, empty, hungry feeling, that terrible fight, in each family the same!"[18] There was talk of some joy when the Allies came closer, but also an ‘empty’ feeling due to the delay of the liberation. Both optimistic and pessimistic messages seemed to increase, such as with Mrs. Chr. Kroes-Ligtenberg, a 30-year-old housewife from The Hague. On April 12th she wrote about the war news: "A blast of optimism for all the people now that the messages, especially those from Mid-Germany are so positive. In our country too there is progress, and the expectations of a rapid liberation vary between a few days and a few weeks."[19] The next day she observed a different atmosphere: "The mood today was not as joyful as yesterday. There is progress, but there is no big news and the sudden death of president Roosevelt casts a shadow on the upcoming victory."[20]

Another example of these mood swings comes from the diary of Mr. Kerkhoven, the 40-year-old professor. He described the tension on April 18th, when rumours circulated that the Allies would soon reach The Hague. "The people become nervous and crabby from the tension. Every day there are the craziest rumours. Because of the magnificent weather everyone is walking around in summer clothes and then you can really see how terribly skinny everyone is."[21] Several days afterwards he wrote the following: "According to the last messages the Allies were 3 km away from Amersfoort and people in liberated areas will pray for us. Well, then it is clear that it will take ages before we are freed."[22] The belief that people would be freed decreased. A.G.M. Batelaan-Van den Berg, a 40-year-old housewife from Leidschendam, wrote on April 5th: "But now, after the evening messages my hope has diminished. The Germans offered more resistance in eastern Netherlands than it initially seemed."[23] Thirty-four diarists demonstrated these optimistic and pessimistic mood swings. Messages such as ‘where the hell are the Allies?‘, ‘why are we being skipped?’, ‘they will never arrive’ and ‘will it be next week?’ occurred in 43 diaries.

A last finding that regularly appeared in diaries was the lack of information. As stated earlier in this article, the power supply went down thus stopping radios, among other things, from working. Moreover, newspapers were no longer published. This led to a large number of war rumours being spread across the Western Netherlands. "Hope lives again, especially because of all the rumours that are circulating. And although we know by now what these rumours are worth, still you cling to them like a drowning man clutches at a straw,"[24] said C.E.A.C. Arnold-Mees, a 40-year-old doctor from The Hague. The rumours that were going around gave him hope. Unlike Mr. Koenraads, the teacher from Delft: "I didn’t hop on my bicycle yet, when the girl next door shouted at me: ‘They have crossed the IJssel’. My first reaction was sceptical. You don’t believe anything anymore and especially now that the last newspaper has gone, the truly trustworthy messages are getting scarcer."[25]

The diarists had mixed reactions towards these rumours. More than half tried to ignore them, like Mr. Koenraads, because they hadn’t been confirmed yet. One of the most interesting rumours and speculations was an invasion on the Dutch coast. On April 19th there was a ‘smokescreen’ off the Dutch coast, an event that is not described in the secondary literature. Martinus Alexander Wertheim, a 40-year-old Jewish man in hiding in The Hague, wrote: "In the morning of Thursday April 19th there was a smokescreen hanging off the entire coast. People are climbing on the roofs to see it. Would the Allies really be planning a landing operation? Airplanes were coming and going: it was a beautiful sunny day, but it was a bit windy. My host, who climbed on the roof of one of the electricity factories, noted that the screen went from the Hook of Holland far up north."[26] S.H. Sprang-Nortier, a 35-year-old housewife living with family on the Rapenburg in Leiden, also described the rumours surrounding the smokescreen: "In the afternoon, talk around town was that there was a smokescreen off the coast from the Hook of Holland to IJmuiden. Talk like that doesn’t have a hold on us anymore, but still, it was a small effort, Clara and I went to the attic to convince ourselves that it wasn’t true. But to our great surprise, when we discovered that indeed off the coast, as far as you could see, there was a thick strip of clouds! That must mean: an invasion!"[27]

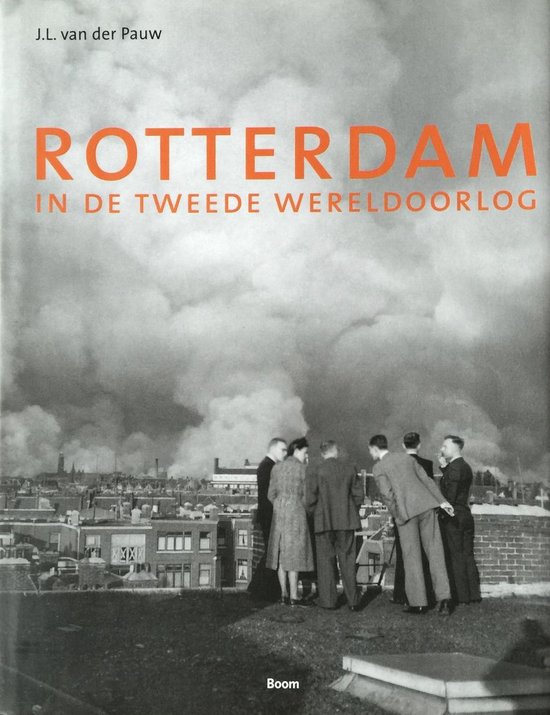

An invasion, retreating Germans or just a fog bank? These kinds of speculations spread quickly in the last month of war. As can be read in the last citation, not everyone believed these rumours straight away. Amongst the 34 diarists that showed mood swings, these rumours were the biggest source of optimism and pessimism. The same mood swings appeared to be taking place in Rotterdam as well. In Rotterdam in de Tweede Wereldoorlog Van der Pauw states that in April and May pessimism and optimism alternated quickly in Rotterdam. This alternation has been linked to the long waiting for and the uncertainty around the liberation.[28]

Definitielijst

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Mid

- Military intelligence service.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Worries about the future, reflection on the past

Finally, prior to the liberation, six diarists were occupied with the future of The Netherlands and were looking back at five years of occupation. They focused especially on the changes within the Dutch society that this period had caused. The 74-year-old Ernst Heldring, a former member of the Upper House living in Leiden, wrote: "The invaders left our country completely broken, a lot destroyed, flooded and deliberately wrecked or taken away. I have nothing to say on this subject: It is well-documented and the expected difficulties in the repair work will confirm it. The morality has sunk in an appalling manner."[29] He noted a decrease in morale during the years of occupation and a collapsing country due to the German domination. Prior to the research, the expectation was that multiple diarists would reflect on the decay of the Dutch society due to German occupiers. It turned out to only occur with a handful of diarists. The reason for this was most likely the miserable conditions, as described in previous paragraphs. People were mostly trying to keep the family alive and to make it through the war instead of reflecting on the past.

D. van Elsas, the 50-year-old chief clerk at a bank in The Hague, wrote very interesting passages about warfare and morale. So too when he talked about cruelties committed by Germany. "How awful it is, is shown in how every generation yearns and strives for a ‘frischen fröhlicher Krieg’ [a fresh, happy war], it shows the way in which these people, like modern Huns, fight a ‘frischen fröhlicher Krieg’. But on top of this all is the disgust it creates among all the people in the world, through the bloodthirsty treatment of the defenseless. In this period 1939-1945, made public in the concentration camps and prisons. Hundreds of thousands, no millions, will not live to tell how they were disgustingly abused before their death."[30]

In addition, people looked forward to the future and to the new world order. Chief clerk D. van Elsas’ statements were interesting here as well. He feared how Germany would be treated after the war: "Nobody wants 1919 to repeat!!! But a radical solution of every gram of Deutschtum ..., the root of evil of two world wars in 25 years’ time. Fighting that feeling from the body of nations to prevent everything from going terribly wrong."[31] Germany should not be punished, like what happened after the First World War with high reparation payments, territorial restrictions and abolishment of the German army et cetera. Naturally, this would cause another war, stated Mr. Van Elsas. A.H.H. Backer van Ommeren, a 30-year-old engineer from a gas company in The Hague, wrote about the future of the Netherlands: "How difficult it will be to start building, without ways of transportation on the tracks, by tram, or even by car. Without fuel and with people’s mentality more aimed at food, robbing, plundering and destroying. Where the work is needed most, the possibilities are few."[32] At the beginning of April, he feared for the rebuilding of the Netherlands.

A final example of looking ahead can be found in the diary of R. Ledeboer, a 35-year-old ophthalmologist from The Hague. He described the founding of an intergovernmental organisation with the goal of preventing disputes between countries: "As primary preamble: the world needs an organisation internationally - to calm down. So 1. Nations should continue to exist. These are sovereign bodies. 2. One needs an international police force. Second preamble: One shall never be able to prevent arguments between nations. That means, chances of war can never be excluded."[33] Furthermore, like Mr. van Elsas, he based a similar section on the situation after the First World War, where a few measures were taken to prevent a new war with Germany. He realised that a League of Nations should be established so that future disputes between countries would be solved peacefully.

Definitielijst

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

- League of Nations

- International league of Nations for cooperation and security (1920 – 1941). The League was located in Geneva, in neutral Switzerland. During the 1930s the league of nations could do little against aggressive behaviour of Japan, Manchuria, Italy, Abyssinia and Hitler. The league of nations was in fact the predecessor of the United Nations.

Conclusion

From this article, several conclusions can be drawn. First, the diary research and the examples presented here show that there were quick shifts between optimism and pessimism. These emotional shifts could be found with 34 diarists. When progress was made on the Western Front and the Eastern Front, when food supplies increased, or when it became warmer outside, an increasing joy was observed among the diarists. This joy could soon disappear due to setbacks on the fronts, such as a heavy resistance from young SS troops near Zutphen, causing the city to be liberated only after four days. Rumours were another important source of these mood swings. Other diarists showed these mood swings too; however it took longer for the swing to appear, or it was less strong. The biggest sources of disappointment were the rumours that were spread around this time. These conclusions are similar to those of Van Der Pauw from his book Rotterdam in de oorlog. He encountered the same mood swings between optimism and pessimism in Rotterdam.

Secondly, from the last month of war it is concluded that the majority of the diarists could barely make ends meet to obtain the food that was available, which caused a lot of dissatisfaction. There were 46 diarists dependent on the soup kitchens and the food bank. There was often no money left for the black market. These diarists consumed less than 340 calories per day and had the most trouble putting something extra on the table. A small group of 13 diarists knew how to get by with the accumulated supplies and the black market. This group held gatherings regularly where there was an abundance of food and where literature or music were being discussed. Social contacts were maintained among almost all diarists. Families looked after each other whenever possible. There is uncertainty around this subject with seven diarists, as they did not write about their private life: the focus in their diaries was primarily at describing the hunger and the approaching Allies.

One last thing that was observed in six diaries was the looking forward to the time after the war and looking back at five years of occupation. When looking back at the period after the war, the changes within Dutch society as a result of this occupation were extremely significant. When looking forward, the establishment of the Netherlands, international cooperation and the treatment of Germany were important. Against all expectations prior to the research, people were mostly dealing with the present. Being freed had the utmost priority. As this took longer than expected, people were not happy. Comments such as ‘it is taking too long’, ‘when will they be here?‘, ‘it is awfully quiet here’, ‘we will just wait’ and ‘will it happen next week’ appeared in no less than 43 diaries. The arrival of the liberators was most important. Everybody looked forward to that.

See also:

- Run-up to the liberation of the Netherlands

- Celebrations in the Netherlands

Notes

- F.J. Wijkhuizen, Dagboek, 38 (10 april 1945)

- C.L.M. Kerkhoven, Dagboek, 83 (22 april 1945)

- Fie van Baaren, Dagboek, 36 (28 april 1945)

- Rudolf Jacob Lodewijk Simons, Dagboek, 841 (1 mei 1945)

- J.S. Bartstra, Dagboek, 249 (eind april 1945)

- W. G. J. Braat-Bertel, Perzisch kleed voor een kistje aardappels - Oegstgeest 1940-1945: Uit het dagboek van Trudy Braat-Bertel (Oegstgeest 2010) 147 (21 april 1945)

- A. D. van Berge Henegouwen en J. A. van Doorn-Beersma, Oorlogsdagboek Han de Wilde (Leiden 2015) 571 (21 april 1945)

- Th. Witting, Dagboek, 45 (1 april 1945)

- Van Riemsdijk, 67 (2 april 1945)

- J. M. G. Beelen, Dagboek, 744 (13 april 1945)

- J. H. Kasten, Dagboek, 36 (29 april 1945)

- Mia Boeree, Dagboek, 74 (29 april 1945)

- A. F. Koenraads, Dagboek, 538 (29 april 1945)

- J. A. J. A. Ladan, Dagboek, 47 (25 april 1945)

- Van Berge Henegouwen en Van Doorn-Beersma, Dagboek, 521 (30 april 1945)

- L. D. J. Thannhäuser, Dagboek, 132 (2 april 1945)

- C. D. M. van Erp Taalman-Kip, Egodocument, 123 (4 april 1945)

- Johan L. van Soest, Dagboek, 32 (5 april 1945)

- Chr. Kroes-Ligtenberg, Dagboek, 94 (12 april 1945)

- Ibidem, 95 (13 april 1945)

- Kerkhoven, 77 (18 april 1945)

- Ibidem, 81 (21 april 1945)

- A. G. M. Batelaan-Van den Berg, Dagboek, 132 (5 april 1945)

- C. E. A. C. Arnold-Mees, Dagboek, 69 (14 april 1945)

- Koenraads, 524 (19 april 1945)

- Martinus Alexander Wertheim, Dagboek, 317 (20 april 1945)

- S. H. Sprang-Nortier en familieleden, Dagboek deel 4 en 5, 41 (19 april 1945)

- J. L. van der Pauw, Rotterdam in de Tweede Wereldoorlog (Amsterdam 2006) 6

- J. Vries, Herinneringen en dagboek van Ernst Heldring 1871-1954 (Groningen 1970) 1455 (5 mei 1945)

- D. van Elsas, Dagboek, 914 (21 april 1945)

- Ibidem, 926 (29 april 1945)

- A. H. H. Backer van Ommeren, Egodocument Backer van Ommeren, 672 (8 april 1945)

- R. Ledeboer, Dagboek, 40-41 (1 mei 1945)

Definitielijst

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Information

- Article by:

- Joshua Rijsdam

- Translated by:

- Barbara Keus

- Feedback?

- Send it!