Introduction

The American Cemetery in Margraten is the last resting place of Captain Walter "Hutch" Huchthausen. Contrary to most other soldiers buried here, Huchthausen did not die while engaged in warfare duties. It was his task to track down objects of artistic and cultural value and to bring them to safety. He belonged to what soldiers among themselves called Monuments Men, a member of the Allied program aimed at protecting Europe's cultural heritage during the war. This article is about these Monuments Men.

Establishment and goals

Cultural heritage in danger

Early in the war, culture lovers in the United States were concerned about Europe's cultural heritage. Most European museums had closed their doors and more than two million art objects had been hastily transferred to temporary repositories. Works of art were safe from bombardment there, but the storage conditions, such as humidity, were by no means always suitable for the storage of the sometimes centuries-old works of art. It was also feared that monumental buildings, such as churches, would be damaged or destroyed during an Allied invasion.

A man who was aware of the importance of preserving artistic and monumental objects from an early age was George Stout, an authority on art conservation in the United States. He wrote a pamphlet in the summer of 1942 with which he wanted to encourage the American government to take action. "In the areas ravaged by bombings and gunfights," he wrote, "there are monuments that are dear to the people of those regions and cities: churches, sanctuaries, statues, paintings and all kinds of works of art. Some may have been destroyed, others damaged. They all run the risk of being further damaged, robbed or destroyed." He advocated a protection program that, in his opinion, would not have a negative impact on the course of the battle. "Protecting these objects shows respect for the beliefs and customs of all people and shows that these things belong not only for certain people, but also to the heritage of humanity. Protecting these matters is part of the responsibility that lies in the hands of the governments of the United Nations."

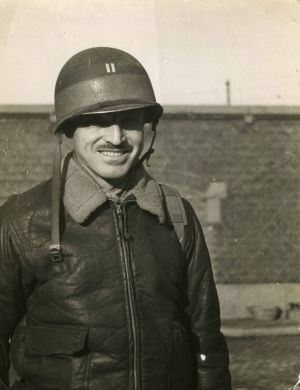

Monument Officer George Stout, an important inspiration for his MFAA colleagues. Source: U.S. National Archives

MFAA

The importance of cultural preservation was recognized by President Roosevelt. On June 23, 1943, he set up a committee led by Judge Owen Roberts to protect "historical and artistic monuments in war zones". The American protection policy initially meant very little. During the campaign in Sicily in the summer of 1943, only two officers were active in the field as art protectors. Their precise assignments were unclear, nothing was arranged in the field of transport and no staff members were assigned to them. Despite the good intentions, things went wrong in the Sicilian capital of Palermo; Allied bombing raids destroyed the historic city centre, including the state library, state archives and botanical gardens.

The Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives Section (MFAA) was decisive for the protection of Europe's cultural heritage. This military section was established at the end of 1943 and fell under the responsibility of the Allied military administrations in Europe. By the end of the war, 350 soldiers and civilians from thirteen countries were to work for MFAA. Most of them worked in the cultural sector, for example as museum director, curator, teacher, artist, architect or archivist. The task of these so-called Monuments Men was clear; to save as much of European culture as possible. George Stout, now a Lieutenant in the Navy, was one of the first to be asked to be part of the program. He became an inspiration to many of his fellow monument men.

That the protection program offered no guarantees was evident on 15 February 1944, when the Abbey of Monte Cassino was completely destroyed by an allied aerial bombardment. It was wrongly assumed that German troops threatening the Allied advance had entrenched themselves in the building. No monument men had been present when the decision was made to destroy the abbey with its unique historical and religious significance.

Definitielijst

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

Invasion of Normandy

Instructions from Eisenhower

Prior to the invasion of Normandy, Commander-in-Chief Dwight Eisenhower gave instructions on 26 May 1944 on how to deal with historical and cultural objects in Western Europe. He emphasized that the "historical monuments and cultural centres" his troops would encounter during the march "symbolizes everything for the world [...] we are fighting for to preserve it. It is the responsibility of every commander to protect and respect these symbols wherever possible". But he made a comment, because "where military necessity dictates, the commanders may order appropriate action, even if this may cause damage to a highly valued location". He cited Monte Cassino as an example, where military interests took precedence over cultural interests. Human lives were more important than monuments and art.

A day after Eisenhower gave these instructions, MFAA sent a list of 210 protected buildings in Normandy to Eisenhower's headquarters. The list was first rejected, but later adopted because it was shown that the majority of these buildings, including many churches, were not suitable for military use. On June 6, 1944, MFAA did not count in Italy the presence of fifteen men: eight Americans and seven British. Seven of them held organizational positions at Eisenhower's headquarters and the rest were assigned to the various Allied armies. They operated in the field with the task of inspecting and preserving all important monuments and art objects found during the Allied advance.

Eisenhower with his wife on the steps of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Source: Monuments Men Foundation

Church Towers in Normandy

Second Lieutenant James Rorimer was active as a monument officer in Normandy. He was curator of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, specializing in medieval art and culture. In Normandy he was assigned to the Communication Zone, the area behind the front line used for military supplies. He did not have his own transport, but rather hitchhiked with a convoy. His first stop was Carentan, a junction between the Omaha Beach and Utah Beach. airstrips. The battle that had raged here from 10 to 14 June had left its mark: the city had been largely wiped out by Allied artillery and aerial bombardments. However, he found the only building on Rorimer's list of protected monuments, the cathedral, virtually intact. Only the tower was slightly damaged.

When inspecting a monument, the monument men had three tasks: to determine the situation, to supervise possible repairs and to prevent further damage by civilians and military personnel. Although there was no immediate risk of collapse, Rorimer ensured that the local authorities would take care of the reinforcement of the cathedral tower in Carentan. He then placed a sign at the cathedral stating in French and English that 'entry or removal of any material or goods' was strictly forbidden.

Rorimer continued his inspection tour. Traces of war were visible in every place, but he found most churches intact, often with the exception of the tower. During the battle the church towers were used by German snipers and observers. Allied troops had aimed primarily at the towers, so that the churches were spared as much as possible. The damage was not limited everywhere: in La Haye-du-Puits, Rorimer had to send the churchgoers away because he feared that the passing military traffic would cause the tower to collapse and in Saint-Malo in Brittany the military supply route even ran right through the remains of the church.

Meeting between the ruins

There was little to save in Saint-Lô. The city was heavily bombed by the Allies and the first American troops did not enter Saint-Lô until July 18. According to later estimates, 95% of the city had been destroyed. The museum was levelled to the ground and the Notre Dame of Saint-Lô was severely damaged. Rorimer noted that before leaving the city, the Germans had placed booby traps on the pulpit and altar of the church. Illustrated manuscripts of the monks of the famous monastery of Mont Saint-Michel, among other things, were lost during the battle. However, it was determined that the destruction of the city could not have been prevented: the city was an important traffic junction and had to be conquered from the Germans who had entrenched themselves here.

The Notre Dame of Saint-Lô which was badly damaged during the battle for Normandy and has not been fully restored since then. Source: Ewoud van Eig

On 13 August 1944, some monument men, including Rorimer and Stout, met at the symbolic location that was Saint-Lô. They were frustrated by the many problems they had encountered in recent weeks. Most of them had no transport of their own, no camera and none of them had a radio receiver. The shortage of "forbidden entry" signs was cleverly solved by Stout: from now on, they would place in stock signs saying: "Danger: mines! But despite all the problems, the men concluded that their operation had been a success so far. The French were grateful to them and most of the commanders were helpful, despite the monument men having an advisory role and no authority.

Bare walls

While the allied troops advanced further towards Germany, the monument men became increasingly concerned with locating works of art. After the liberation of Paris on 25 August 1944, Rorimer made an inspection visit to the Louvre. In the previously crowded museum he found empty corridors and bare walls. The works of art had been transferred in 1939 and 1940 to country houses and remote castles, where they were safe from war damage. With the exception of two minor pieces of German origin, the French national art collection was left untouched by the Germans. Meanwhile, a new exhibition was being worked on and the first works of art returned to the museum.

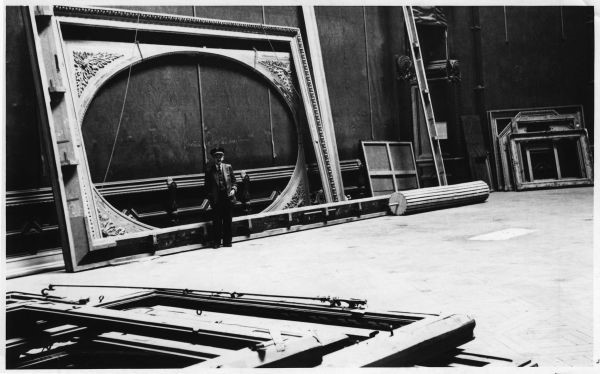

Part of the collection of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam had also been transferred to a safer destination on the eve of the war. Accompanied by Captain Walker Hancock, a well-known American sculptor, Stout visited an art storage facility in a marl cave in the Sint Pietersberg near Maastricht in October 1944. Stored in the cave were paintings from the Rijksmuseum. Rolled up in a tube, they found Rembrandt's The Night Watch. After first being housed elsewhere, the painting had been transferred to Maastricht in 1942. Stout concluded that the years of storage had not done the painting any good: it had turned yellow, but it could have been much worse. On 25 June 1945, the masterpiece returned to the Rijksmuseum by barge.

The Night Watch returns to the Rijksmuseum. The curtain is carefully unrolled on 30 June 1945 after having been kept rolled up for several years, most recently in a marl cave near Maastricht. Source: U.S. National Archives

Definitielijst

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

In Germany

Art Theft

The return of art did not always go so smoothly. During the years of occupation, the Nazis had massively robbed art in Western Europe. In all liberated areas the monument men discovered that art had disappeared. These were works by the great masters, such as Michelangelo, Rembrandt, and Vermeer. Religious relics, altar statues, jewellery and archives, for example, were also taken to secret warehouses in Germany.

Adolf Hitler donates a painting by the 19th century Austrian painter Hans Makart to Hermann Göring. In contrast to many other works, this painting was acquired legally. Source: Library of Congress

Art had also been stolen for the museum that Hitler wanted to open in Linz, Austria, after the war. Michelangelo's marble sculpture Madonna with Child (the Madonna from Bruges) and the multi-panel The Lamb of God (the Ghent altarpiece) by the Van Eyck brothers were stolen in the name of the Führer. Other works of art ended up in the hands of the greedy Reigh Marshal Hermann Göring. The walls of his country house Carinhall were decorated with full of looted paintings, different styles and periods crisscrossed. After the war he learned in Allied captivity that his showpiece, Vermeer's Christ and the adulteress, was a forgery of the Dutchman Han van Meegeren.

Much of the stolen art was privately owned, especially by Jews. In Paris alone, an estimated 22,000 works of art were stolen by the Nazis. Most of these works of art were confiscated by the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg, an organisation led by Nazi ideologist Alfred Rosenberg who was involved in confiscating Jewish household goods in France, Belgium and the Netherlands. A museum employee at the Parisian museum Jeu de Paume told Rorimer that the Einsatzstab had taken the art to Neuschwanstein Castle in the Bavarian Alps.

From Aachen to Siegen

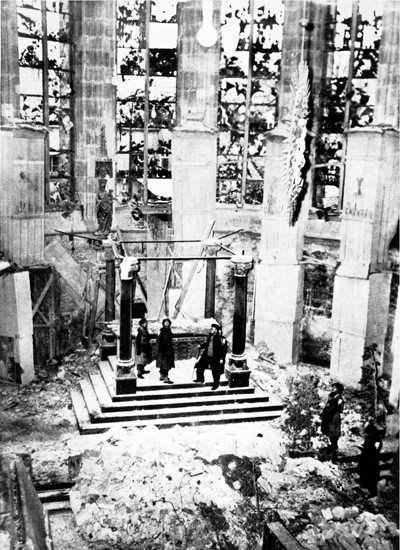

Neuschwanstein Castle in Bavaria and other art repositories of the Nazis were still in enemy territory in the autumn of 1944, but the monument men were already active in the already conquered western part of Germany. Hancock visited Aachen in October 1944, where a battle had raged from 2 to 21 October. The city was bombed by the U.S. Air Force and bombarded with mortars. In the Cathedral of Aachen, Hancock saw the consequences of the violence of war. All stained glass windows were shattered and brickwork lay all over the floor. Mattresses, dirty blankets and food remains had been left behind by the Germans who had sought refuge in the cathedral during the bombardments. An Allied bomb had pierced the apse and destroyed the high altar but had not gone off. The vicar told Hancock that the relics had been removed by the Nazis. Most of the works of art from the Suermondt Museum had also been transported to a copper mine in the slightly eastern located Siegen.

On 2 April 1945 Stout and Hancock inspected the mine in Siegen. Sculptures, paintings and altarpieces were stored in racks reaching up to the ceiling. The monument officers recognized the works of Rembrandt, Van Gogh and Rubens, among others. In some paintings the paint layer was damaged and several canvases were mouldy. Six crates were also found in the mine containing the missing relics of Aachen Cathedral, including the silver bust of Charlemagne containing part of his skull. Also found was the collection from Beethoven's house in Bonn, including the original manuscript of his Sixth Symphony. Everything found in Siegen came from West Germany. The search for looted art from the rest of Western Europe had to continue.

In the line of fire

On April 2, Walter Huchthausen and his assistant Private Sheldon Keck, who was an art curator by trade, were east of Aachen in a jeep on their way to the front to locate an altarpiece. Before the war, Huchthausen was a design teacher at the University of Minnesota. In 1942 he had joined the American Air Force. After he was wounded in a bombardment in London in 1944, he was appointed monument officer in the American Ninth Army. In Aachen, he set up a building board to coordinate all emergency repairs and set up a collection point in the Suermondt Museum for works of art found in the area of the Ninth Army.

On the day that he and Keck were on their way to the front, there was still ongoing fighting in the Ruhr area. However, the men felt safe in the area they thought was behind the front line. When they stumbled upon American soldiers everything seemed to be in order, but suddenly their jeep was shot at by Germans. American soldiers returned fire and brought Keck to safety. Huchthausen was taken by ambulance. For two days, Keck searched in field hospitals in vain for his superior. Eventually he found his name on the list those of killed. Huchthausen was killed by the gunfire. His body had pressed Keck's body to the floor of the jeep, so the assistant had survived.

Treasuries of Merkers

In the weeks following Huchthausen's death, his colleagues made discovery after discovery, for example in the Merkers salt mine in Thuringia where the Americans arrived on 8 April 1945. The complex included more than twenty-five kilometres of tunnels and had twelve entrances. Part of the underground complex was filled with treasures, including ancient Greek and Roman works, Byzantine mosaics and thousands of paintings from Berlin museums. Most of the monetary reserves of the German treasury were also stored here. Counted were 8,198 gold bars, 711 bags of American gold and enormous amounts of German and foreign currency. In the part of the mine used by the SS, large quantities of jewellery, watches, glasses, wedding rings and gold teeth were found that belonged to the Jews murdered in the extermination camps.

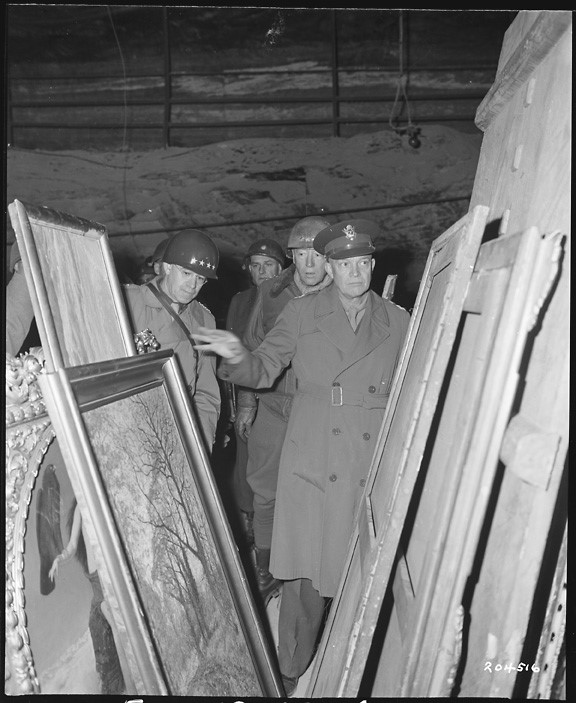

On 12 April, generals Eisenhower, Patton and Bradley visited the mine to see the treasure chambers with their own eyes. Stout had other things on his mind, because he and his colleagues had to take care of the rapid evacuation of the mine. It was located in the Soviet zone and it was necessary to prevent the valuables from falling into the hands of the Soviets. Stout had the works of art wrapped in sheepskin coats that had been found in a storage room of the Luftwaffe in the mine. They were then transported to an art depot in Frankfurt.

Eisenhower, Bradley and Patton inspect paintings in the Merkers salt mine on 12 April 1945. Source: U.S. National Archives

Fairy-tale castle and coffins

In April 1945 the Bavarian castle Neuschwanstein was also taken by the Americans. The treasure chambers of the fairy-tale castle, built in the 19th century by order of the eccentric King Louis II of Bavaria, remained closed until monument officer Rorimer arrived on 4 April. He found coffins with the abbreviation ERR (Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg) on them. The castle was the main depot for the storage of the precious household goods and other possessions of mainly French Jews that the organization had appropriated. It also housed the jewellery collection of the Jewish banking family Rothschild. "I walked through the rooms as if in a trance," Rorimer wrote, "hoping that the Germans would lived up to their reputation for orderliness and that they would have photographs, catalogues and notes of all these things. Without them it would take twenty years to bring home the accumulated spoils of war." And indeed, he found in the castle the archives of the ERR that helped to identify and return the objects to their owners or their next of kin.

Neuschwanstein Castle, the former main depot of the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg. Source: U.S. National Archives

A remarkable find was made by American soldiers in a salt mine in Bernterode in Thuringia. They found four coffins with on one of them a wreath with red ribbons and a name: Adolf Hitler. On 1 May, Stout and Hancock identified the coffin as that of the Prussian king, Friedrich Wilhelm I, who died in 1740. The decorations were Hitler's tribute to "the King of Soldiers". The other coffins belonged to President Von Hindenburg and his wife and to Frederick the Great, son of Friedrich Wilhelm I. Precious artifacts of the Prussian monarchy were also found among the coffins, including the crown with which Friedrich Wilhelm I was crowned in 1713.

Art treasures in Altaussee

In a salt mine near the Austrian village Altaussee several missing (foreign) masterpieces were found. The salt mine had been claimed by Hitler for personal use. He had ordered that all art for his future museum in Linz should be stored here. Between May 1944 and 1945, more than 1,687 paintings from Hitler's Munich office arrived here. On 10 and 13 April, eight chests were brought into the mine. On the outside it was written that they contained marble, but in reality they contained 500 kilos of explosives. It was the intention of the local Gauleiter, August Eigruber, to blow up the mine and its irreplaceable contents. He was inspired by Hitler's Nero-order, which ordered the destruction of the German infrastructure to stop the Allied advance.

Captain Robert Posey and Private First Class Lincoln Kirstein, respectively architect and cultural agent by profession, arrived at the mine on May 16. The entrances had collapsed and were blocked by debris. Fortunately, miners commissioned by their management had thwarted Eigruber's plans to protect the art. In early May, with the approval of Ernst Kaltenbrunner, the head of the Reichssicherheitshauptamt, they had removed the heavy bombs and detonated the mine entrances. Posey and Kirstein ordered miners to make a small passage through the rubble and crawl in through it. In the flickering light of their carbide lamps, they beheld masterpieces of European heritage. They found the Ghent altarpiece, the Madonna from Bruges and Vermeer's The Astronomer, among others. They counted 6,577 paintings, 230 drawings and watercolours, 954 prints and 137 sculptures.

Because the mine was located in the Soviet zone it had to be evacuated as a matter of urgency. Stout supervised the packaging of the precious works of art. Packing the Bruges Madonna and the panels of the Ghent altarpiece took a whole day. "I think we can let her bounce from Alp to Alp, all the way to Munich, without any damage," said Stout about the carefully wrapped Bruges Madonna.

Wrapping up the Ghent altarpiece. The man with the N of Navy on his uniform is monument officer George Stout who initially served in the navy. Source: U.S. National Archives

Definitielijst

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- Gauleiter

- Leader and representative of the NSDAP of a Gau.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Luftwaffe

- German air force.

- Marshal

- Highest military rank, Army commander.

- mine

- An object filled with explosives, equipped with detonator which is activated by either remote control or by colliding with the targeted object. Mines are intended to destroy of damage vehicles, aircrafts or vessels, or to injure, kill or otherwise putting staff out of action. It is also possible to deny enemy access of a specific area by laying mines.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

Epilogue

After the war

After the war ended, the work of the monument men continued. It took them another six years to archive and return all the art and cultural goods found to the country of origin. In southern Germany alone, they had found 1,000 warehouses that needed to be inspected and cleared. New employees were assigned to MFAA for this gigantic task.

All works of art and other objects had to be returned to their original owners, even if they were German property. Transportation took a lot of time and care. This was the case, for example, with the stained glass windows of Strasbourg Cathedral. After the fragile glassware had been removed from a salt mine in Heilbronn, it was carefully packed in 73 crates. They were returned by convoy in October 1945. On 4 November, the return was celebrated with an elaborate ceremony, during which Rorimer was awarded the French Légion d'honneur.

Many works of art were never recovered and are believed to have been lost. Thousands of paintings were never claimed because the owners had perished. Sometimes it took decades before works of art were returned to the original owners or their next of kin, for example in the case of the collection of the Dutch Jewish art dealer Jacques Goudstikker. It was only in 2006 that the Dutch government, which owned a large part of the collection, decided to return it to the heir, Goudstikker's daughter-in-law.

Lessons for the present

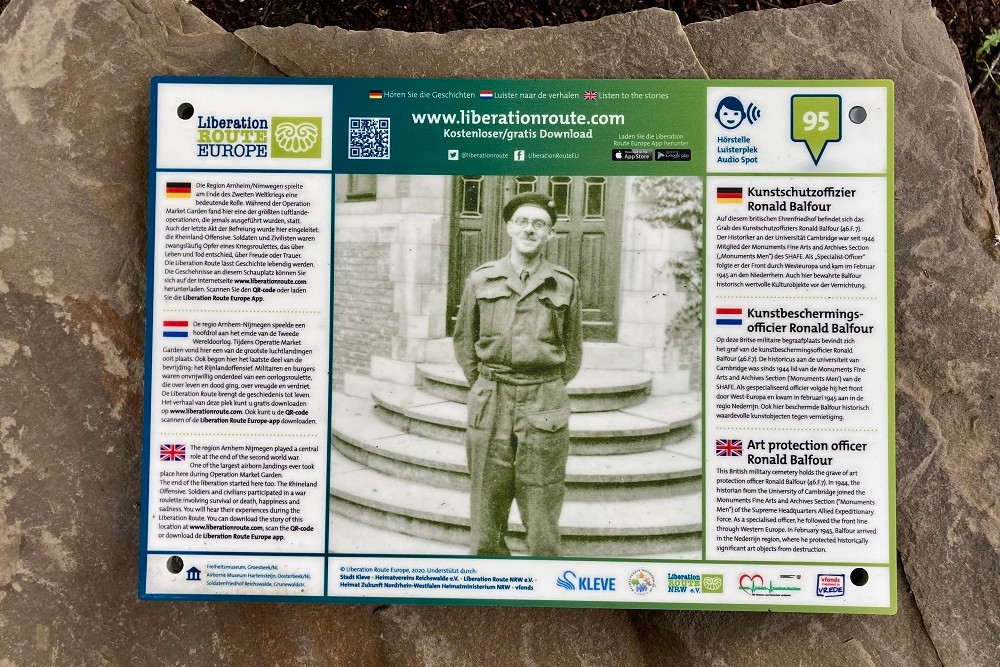

Two monument men were killed while carrying out their work: the British historian Ronald Balfour, who was killed in a grenade attack in Kleve on 10 March 1945 while clearing a church, and Huchthausen. "He was a great guy," Walker Hancock wrote to his wife about Huchthausen "who truly believed in the fundamental goodness of all people. ... Hutch's attitude toward his mission in this war is one of my best memories. The buildings he had hoped to build as a young architect will never be built ... but the few people who have seen him at work - friend and foe - should have a better picture of mankind thanks to him". David Finley of the Roberts Committee, who would later become director of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, praised Huchthausen in a letter to his next of kin as "one of the outstanding monument officers in the field. His work in the Loire Valley and in Aachen will continue to make a significant contribution to the cultural preservation of Europe".

Huchthausen, Balfour and their colleagues who did survive the war not only deserve our attention because of their contribution to the preservation of our cultural heritage, but their work also contains a lesson for contemporary wars. A lesson from which little seems to have been learned. The MFAA veterans must have looked with sadness at the television images of Iraqi citizens who during the Iraq war in 2003 fetched centuries-old antiquities from the National Museum in Baghdad. Many pieces have been found by now, but others are still being searched for...

Definitielijst

- mine

- An object filled with explosives, equipped with detonator which is activated by either remote control or by colliding with the targeted object. Mines are intended to destroy of damage vehicles, aircrafts or vessels, or to injure, kill or otherwise putting staff out of action. It is also possible to deny enemy access of a specific area by laying mines.

Information

- Article by:

- Kevin Prenger

- Translated by:

- Fernando Lynch

- Published on:

- 19-01-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!