Asterdorp, the fourth ghetto of Amsterdam

The situation in Amsterdam at the beginning of the 20th century

As in large parts of West-Europe, the population of Amsterdam also grew in the beginning of the 20th century. This increase was reflected in the housing: the small labourers’ houses where large families lived in, were bursting at the seams. These families often lived a poor life. Because of this, there was a huge need for social housing.

Because of the addition of the municipalities of Sloten, Watergraafsmeer, Buiksloot, Nieuwendam, and Ransdorp, the size of the municipality of Amsterdam almost quadrupled in 1921. Consequently, the demand for (cheap) housing could be met, that was built in the so-called ‘garden villages’ of Oostzaan, Nieuwendam, and Buiksloot.

City councillors with a vision who were responsible for the realisation were: mayor Monne de Miranda, the councilwoman of public housing, and the ‘soul’ of the College, Floor Wibaut, ‘the Almighty’ (‘Who builds? Wibaut!’). They were accompanied by contractor Willem de Vlugt and the driven CEO of the municipal housing service, Arie Keppler.

Asterdorp until the Second World War

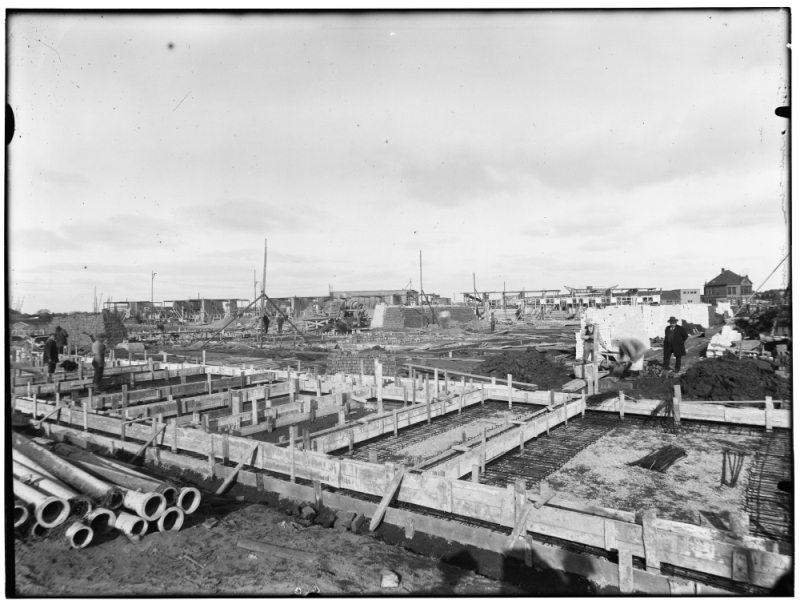

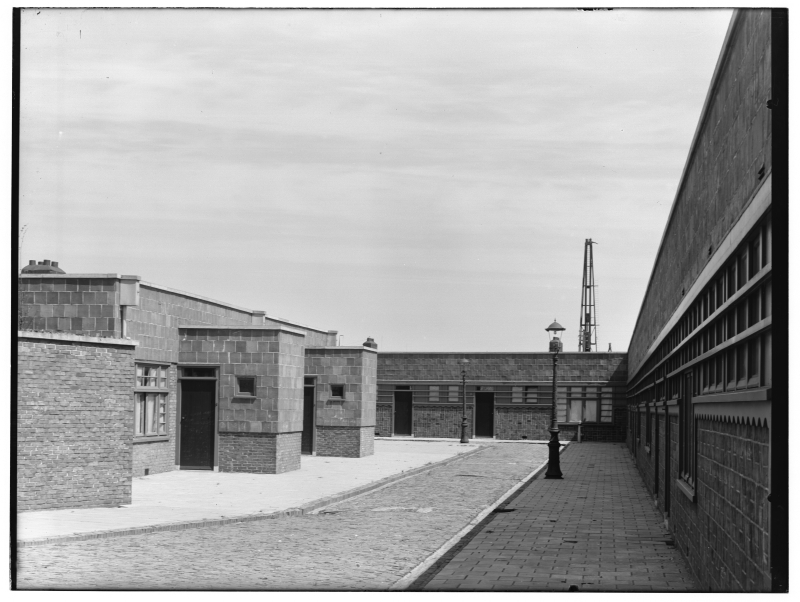

Some labourers and their families that lived and worked in terrible circumstances until that time, were seen as ‘inadmissible’ for state housing by the Gemeentelijke Woningdienst (GWD, Municipal Housing Service). In Amsterdam-North in 1927, a suburb was created with 132 houses on an industrial site built with a wall around it for precautionary measures. This ‘live-in school’ was named Asterdorp. Until 1940, around 450 families lived in Asterdorp, in total around 3000 men, women, and children.

Because of the effort of a female supervisor, people wanted to transform these families into ‘decent’ families who, through proof of good behaviour, would be assigned a house of the GWD. However, private as well as corporation housing would still be out of reach.

Many didn’t wait for a regular move to a GWD house. They left Asterdorp prematurely, because they kindly declined the stigma that was placed unto them for living in Asterdorp. A stigma that took away an honest chance on the job market. They ended up in shacks or on houseboats.

A large number however, managed to get a more expensive (private or corporation) house. They went to project developers of new expensive rentals (with rent from ƒ7,50 per week). There were too many of these houses, so they were empty. Project developers didn’t lower the rent, but gave new tenants 1 or 2 weeks of free housing. New tenants moved into these houses and stayed as long as they could pay rent. If they would again be evicted, they would go to one of the other project developers.

Asterdorp in the Second World War

On 14 May 1940, Rotterdam was bombed. Homeless families found (temporary) roofs over their heads in Asterdorp. After they had left, the village was seized by the German occupier. During that time, some of the original residents still lived there, of which the last ones would leave in the spring of 1941. After they had left, the village was empty for some time.

In the beginning of March 1942, the German authorities stated that the complex would be redeveloped for housing Jewish families. The redevelopment was finished in May.

The fourth ghetto

In the Second World War, Amsterdam knew 4 areas where Jews were concentrated awaiting deportation to the destruction camps:

- the Jodenbuurt (the area around the Staalstraat until the Peperstraat)

- the Transvaalbuurt

- the Rivierenbuurt

- Asterdorp

An eyewitness reports

Simon Waterman lived in Asterdorp with his family in 1943 for about 6 months:

"No idea how we got there, with all the others. Jews had to be concentrated in certain areas. Then they could easily get caught in some raid. And Asterdorp was such a place. All these houses were connected to each other and formed - well, you know. So it was easy to close off and then you would have them all."

"They emptied the house. It always happened at night in some way and was very quiet. That was very peculiar. The family was suddenly gone. I went to get that girl, looked inside and I saw plates with food on the table. Apparently they were taken in the dark. And that’s how it went: silently.

"To me, Asterdorp means that I feel things differently than other people. Yes. I don’t know. It left psychological scars carved into your soul. That’s how I would like to put it and it’s just there. I’m different from other people. I think. Others don’t think so, that’s how I feel."

Until June 1943, 307 Jewish people lived in Asterdorp. Of them, 227 were killed. The Dutch Jews in Asterdorp were some of the last that were still in Amsterdam. In the beginning of June 1943, Asterdorp was cleared, the remaining residents were housed in the Transvaalbuurt.

Asterdorp 1945 - present

After the Second World War, Asterdorp did not succeed in being transformed into a normal suburb. All the houses were demolished. Since 1955 the area is again an industrial park.

Asterdwarsweg 10, gate house of the former Asterdorp. Ex- studio of artist André Volten. Source: Amsterdam City Archive / Eijnden, Janus van den

Acknowledgement

In 2014, the Verbond Belangenbehartiging Vervolgingsslachtoffers (VBV, Union for Advocacy for Victims of persecution), had a meeting in Bonn with the German authorities. During this meeting, the Jodenbuurt, the Transvaalbuurt, and the Rivierenbuurt were officially acknowledged as ‘Judenviertel’ (Jewish quarters) and as ghettos.

Sixty-nine years after the Second World War ended, this acknowledgement is very important, because it made the way for a one-time ‘ghetto benefit’ of 2000 Euros. This benefit is intended for people who lived in the Jewish ghettos in Amsterdam during the Second World War and carried out ‘non forced’ labour for the German occupier.

The excitement that this acknowledgement brought was so great, that people forgot to address the status of Asterdorp. In 2015, Asterdorp was finally acknowledged as ‘Judenviertel’. The VBV was helped by film maker Saskia van den Heuvel, maker of the documentary Het vergeten getto (The forgotten ghetto).

Definitielijst

- ghetto

- Part of a town separated from the outside world to segregate Jewish population. The establishment of ghettos was intended to exclude the Jews from daily life and from the rest of the people. From these ghettos it was also easier to deport the Jews to the concentration and extermination camps. Also known as “Judenviertel” or Jewish quarter.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

Information

- Article by:

- Paul van de Kar

- Translated by:

- Barbara Keus

- Published on:

- 19-12-2020

- Feedback?

- Send it!