Canada's "Charge of the Light Brigade"

Introduction

Norrey-en-Bessin, 1944. Lieutenant George Gordon of the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade drove his Sherman tank at such a speed around a curve that it turned over, leaving imprints on the small building at the corner. He retreated to Norrey-en-Bessin for a German counterattack from Le Mesnil-Patry. The imprints should still be visible, although there are no pictures of them.

Norrey-en-Bessin, 2011. My travel companion points at muddy tractor tracks in the asphalt. No, those are not the ones, and we continue searching. Unfortunately we do not find anything and walk back to the car. Precisely there, where we had stared at the asphalt, were the imprints … still clearly visible in the old wall…

The situation prior

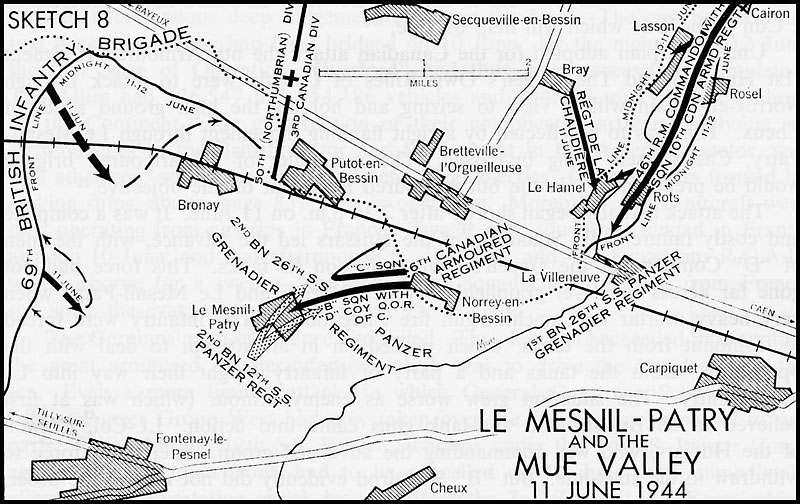

D-Day, 6 June 1944, the start of Operation Overlord, the Allied forces landing in Normandy and the start of the liberation in the west. American, British and Canadian troops went ashore on five different beaches. In the middle it was the British 50th Infantry Division that landed on Gold Beach. East of there, the Canadian 3rd Infantry Division landed on Juno Beach. During the days after D-Day both units moved inland -- the British towards Tilly-sur-Seulles and Villers-Bocage and the Canadians towards Carpiguet and Caen. The gap that developed between the two divisions was filled by the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade. Her regiments also landed ashore on D-Day, all supporting the Canadians on Juno Beach.

The Canadians of the 3rd Infantry Division already managed to reach the Caen-Bayeux railway on June 7th. With this the troops of the Regina Rifle Regiment succeeded in capturing Norrey-en-Bessin. This location served as a sort of bridgehead on the other side of the railway. On the right flank, against the 50th Infantry Division, the Royal Winnipeg Rifles were located in Putot-en-Bessin. This front would remain unchanged for the next four days, during which only the British on the right flank could further advance.

On June 11th the British 69th Brigade, part of the 50th Infantry Division, had almost advanced up to Tilly-sur-Seulles. They managed to reach the villages of Audrieu and Saint-Pierre northeast of Tilly. From there they were given the assignment to attack that day in a south-easterly direction towards Brouay and Cristot. Both places border Le Mesnil-Patry on the west.

The initial plan

On June 10th the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade started with planning a southern attack from Norrey-en-Bessin. The goal of the assault was advancing to the same line as the British 69th Brigade on their right flank. The assault was planned for June 12th. It would be the first time that the Canadian brigade could devise and carry out a plan of their own. Previously the units of the brigade had always been deployed in support of infantry units.

The 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade was under the command of Brigadier Robert Wyman. The brigade included the 1st Hussars (6th Armoured Regiment) and The Fort Garry Horse (10th Armoured Regiment), under commands of Lieutenant Colonel Ray Colwell and Lieutenant Colonel Ronald Morton, respectively. On June 10th at 21:00 hours, Wyman held a conference with these two officers. The plan was to advance south towards Cheux on June 12th. The Forth Garry Horse would then sweep the Mue Valley whilst the 1st Hussars would advance to Cheux itself. Colwell held his own O-Group meeting at 04:00 hours, and there he communicated that his staff would have 24 hours to prepare. Moreover, in preparation for this assault, Wyman had decided to move his headquarters from Basly to Bray. It was during this relocation that new orders came in.

Quick adaptations

Lieutenant General Miles Dempsey, as commander of the British Second Army, held his own conference on June 10th, where, as a part of Operation Perch, it was decided to perform a pincer movement the next day in order to conquer Caen. This eventually resulted in the famous Battle of Villers-Bocage on June 13th. For this reason it was decided to expedite the Canadian operation in support of the attack by the 69th Infantry Brigade. Dempsey had learned from his intelligence that the Germans were planning a counterattack, and he wanted to forestall this assault. However, it would take fifteen hours before this information reach the 2nd Armoured Brigade. Ultimately Wyman would get to hear it at 07:30 hours on June 11th.

At 08:00 hours the 1st Hussars were told that the assault would start at 13:00 hours. A little after 10:00 hours the commander of The Queen’s Own Rifles, Lieutenant Colonel J.G. Spragge, was also informed that his battalion would attack a couple hours later. Around 11:00 hours Brigadier Wyman had his O-Group meeting. Both commanders, Colwell and Spragge, protested and asked for more preparation time. However, Wyman indicated that wasn’t possible. The attack consequently was organized on a very short notice without sufficient preparation (for example, artillery support). The plan was to drive around Cheux via Norrey-en-Bessin and Le Mesnil-Patry toward the eventual target, the higher ground south of Cheux, also known as Hill 107. 1st Hussars and The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada were deployed for this. The rest of the 2nd Armoured Brigade would follow as soon as the target was reached.

D Company (under Major J.N. Gordon) of the Queen’s Own would lead the attack and take Le Mesnil-Patry. Once the village was taken, A Company (Major H.E. Dalton) would pass through and take the crossroads half a mile beyond the village. B and C Companies would subsequently drive tanks to the higher positioned terrain 5 miles further on (south of Cheux).

D Company was attached to B Squadron of the 1st Hussars (Captain R. Harrison), followed by C Squadron (Major D.A. Marks), the headquarters of the 1st Hussars and A Squadron.

Charles Martin, Company Sergeant-Major of A Company, The Queen’s Own Rifles [QORs], wrote the following about the start of the Battle of Le Mesnil-Patry: "The QORs were being asked to push forward seven miles against unknown opposition. We had no information on the enemy. There were none of the usual aerial photographs. There was no opportunity to send out patrols. It made no sense, so the whole idea of this action seemed suspect." … "There was a fair amount of confusion, which did nothing to reassure any of us."

The Canadian advance

The Canadians left from Bretteville, across the railway towards Norrey-en-Bessin. The precise time when the troops left on June 11th remains unclear. As a result of the Allied minefields around Norrey, the tanks were forced to move through the village itself. These minefields caused so many problems that at 13:20 hours the 2nd Armoured Brigade made the urgent request to 3rd Infantry Division for more information concerning other possible minefields in the area.

B Squadron, 6th Armoured Regiment (1st Hussars Regiment), drove ahead with the troops of D Company, The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada, on the tanks. They had already been discovered by the radio surveillance of the 12. SS-Panzer-Division "Hitlerjugend". When the column manoeuvred through Norrey and turned right towards Le Mesnil-Patry they were fired on by the German artillery and mortars. Meanwhile, the tanks of B Squadron had already passed through Norrey, so they did not face problems with the artillery. C Squadron, on the other hand, was in the middle of it. Colwell drove back there and hit a mine with his tank in Norrey, losing a track. He got out to solve the traffic chaos in the hail of artillery and decided to send his headquarters tanks and A Squadron back to Bretteville in order to support the advance of B and C Squadrons from there.

The assault started at 14:30 hours. The German Pioneers at the frontline lay camouflaged in a wheat field. They were given the instruction to let the Allied tanks drive by and to attack the infantry following them. Since the Canadian infantry rode along on the first tanks the Germans opened fire immediately. The infantrymen jumped off the tanks and found themselves in a man-to-man-fight with the Germans. Meanwhile the tanks continued moving whilst firing and were subsequently attacked by the Pioneers with anti-tank rifles, Panzerfausten and magnetic mines.

Pionier Gassner put a magnetic mine on one of the Shermans but was then killed by the tank’s gun. The tank itself exploded shortly after. Pionier Lütgens managed to eliminate another Sherman with a Panzerfaust.

For a lack of artillery support from his own units, Lieutenant Colonel Spragge, the commander of the Queen’s Own, gave his mortar platoon instructions to give as much support as possible. Lieutenant Ben Dunkleman, the platoon commander chose a thickly walled barnyard in Norrey in which to put his mortars. Once the assault had started and the Canadians came under heavy fire, Dunkleman saw plumes of smoke coming out of four grain heaps. He gave the order to fire on them with smoke grenades and soon they were lighting up. These four camouflaged German positions were silenced. The disadvantage, however, was that the Germans now knew where the mortars were located and the platoon was soon bombarded by German artillery and mortar fire.

Meanwhile, the first units had advanced 300 yards (274 meters) to Le Mesnil-Patry. Soon half of the infantry and tanks were eliminated. The survivors of D Company painstakingly managed to cover the remaining 900 yards towards the village. The tanks of B Squadron had in fact been rushed by Captain Harrison to make a move towards Le Mesnil-Patry. However, when the tanks neared the village they were attacked by the well-camouflaged Jagdpanzer IV’s of SS-Panzerjägerabteilung 12. Despite this, a number of tanks and infantrymen succeeded in entering the village. Indeed, at 15:15 hours the village was declared secured. A few minutes later, however, Captain Wildgoose reported that German tanks were approaching from the west. These were the tanks of SS-Sturmbannführer Prinz, to which we will come back later.

Major Gordon, commander of D Company, had in the meantime been wounded. One of his platoon commanders, Lieutenant George Bean, was also wounded (in his leg) but nevertheless took eight men and two tanks to enter Le Mesnil-Patry via the right flank. They were able to cause a lot of damage to the Germans there, even though Bean got wounded a second time, this time in his back. After the tanks’ radio failed and Bean got wounded for the third time, Sergeant Scrutton decided to withdraw. Everyone was put on the tanks and they raced back to their own lines. Of the nine men, two were killed, one was missing, and two wounded. Bean would receive the Military Cross for this action.

Siegel’s counterattack

Around 14:00 hours SS-Obersturmführer Hans Siegel was on his way to an award ceremony at the headquarters of II. Abteilung, 12. Panzerregiment, south of Fontenay. Siegel was the commander of 8. Kompanie. Just outside of Fontenay he encountered his own commander, SS-Sturmbannführer Prinz. He had received a request from SS-Obersturmbannführer Wilhelm Mohnke, commander of the 26. SS-Panzergrenadier-Regiment, for support. Prinz ordered Siegel to turn back immediately to investigate. Back at his company, Siegel took three tanks and left for Le Mesnil Patry.

Siegel drove in front in the first Panzer IV tank. The hedge they drove by suddenly ended, and a number of Shermans appeared on the left flank. "Enemy tanks left – 9 o’clock – 200 – fire!" Quickly four or five Shermans were on fire. The last tank had approached to 100 meters though. "Enemy tank sharp left – 10 o’clock – 100!" This last tank too exploded. The other two German tanks could now advance past the hedge. Their advance continued to the main line of resistance where Siegel eliminated two more Shermans 1.200 meters away.

Siegel’s advance continued but came across heavy anti-tank fire from the Canadians. Consequently his three tanks were quickly destroyed. Simultaneously the units of the 1. Pionierkompanie had started a counterattack. They were able to capture or beat back all of the advancing Canadians.

Prinz’s counterattack

After Prinz had sent SS-Obersturmführer Siegel on his way, he received further information about the scope of the Canadian attack and decided to deploy the not-yet-deployed tanks of his II. Panzerabteilung. They were all Pzkpfw IV tanks and not "Panther" tanks. 5. Kompanie drove across the northside of Le Mesnil-Patry to the west and 6. Kompanie through the village. They quickly encountered C Squadron from the 1st Hussars, who were operating on the right flank in support of B Squadron. It was around 16:15 hours.

Major Marks, the commander of C Squadron, reported at that point to Colwell that he was under fire from a large number of anti-tank weapons. Marks thought this was the British 69th Brigade which had planned an attack on Brouay and Cristot in that direction. After checking with Colwell and Colwell with brigade, Marks gave the order for a ceasefire and the display of recognition flags. Since he couldn’t forward this message by radio to his other tanks, Marks stepped out of his own tank to order the others in person, all the while he was under heavy fire and tanks around him were exploding.

Once back in his tank he communicated to Colwell he could not remain in his position because of the amount of shooting. Colwell then gave the order to withdraw. Shortly afterwards the German tanks and troops became visible.

The Canadians retreat

Colwell gave the order to retreat at about 16:30 hours. The operation had clearly failed, and he expected a strong German counterattack. He forwarded this order to the commanders of B Squadron (Harrison) and C Squadron (Marks). Only Marks acknowledged that he had received the message; no response came from Harrison. Captain Cyril Tweedale had command over a number of tanks of The Fort Garry Horse which temporarily had been put under Marks’s command. Tweedale and Marks were the only two remaining tanks from their squadron.. The rest had either been destroyed or had already retreated. They created a smoke screen to cover the retreat. This was around 17:00 hours. Tweedale encountered Gordon's overturned Sherman blocking the road. By driving through several walls in Norrey he could eventually retreat.

Lieutenant George Gordon had driven round the corner so fast that his Sherman had overturned and his tracks had left marks on the wall of the house. Unfortunately, this blocked another road through the village. Going around was not possible because the area was full of mines laid by the Regina Rifles.

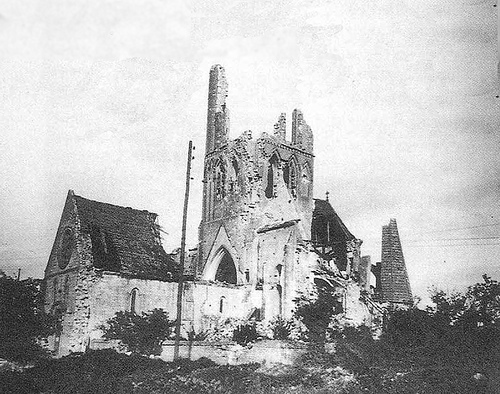

The German artillery fire had destroyed many buildings in Norrey-en-Bessin, and the village was covered in debris. Meanwhile Colwell was busy retreating the tanks of C Squadron . They were given the instruction to drive through walls in order to get to the other side of the village. One of the tanks drove through a wall and landed in the cellar of a house. Another one drove straight through the wall of the yard where Dunkleman’s mortar platoon was stationed, narrowly missing the soldiers.

In the meantime Wyman had ordered Colwell via radio to stay where he was, so that reinforcements could be sent to him. Colwell, however, never received this message and was already located 1.000 yards (914 meters) north of Norrey-en-Bessin. Major Frank White (Second-in-Command of the 1st Hussars) thereafter organized a defence line across the railway with tanks of 1 Troop, A Squadron, and what was left of C Squadron.

Losses

A number of soldiers of the 1st Hussars thought they had ended up in a heavy German attack by an entire panzer division. This belief was even endorsed by Lieutenant-General Guy Simonds, commander of the 2nd Canadian Corps. He specifically said the next day: "While the battle yesterday seemed futile, it actually put a Panzer Division attack on skids." These soothing words were unfortunately not fully based on truth: there was no further German attack planned for that day. Although Dempsey had received a message that an attack was planned, this had already been postponed by Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel, commander of Heeresgruppe B.

The 1st Hussars lost 34 Shermans and 3 Fireflies during the battle, and there were 80 casualties in dead, wounded and missing. The Queen’s Own Rifles lost 96 men out of the 105 who went into action that day.

The Germans lost a similar number of men (189) but significantly fewer tanks. Several sources, including the war diary of the 1st Hussars, indicate that 14 German tanks were lost. 12. SS Division confirmed only the destruction of Siegel’s three tanks. Of these three, one was repaired later. The losses in troops were divided as follows: 26. SS-Panzergrenadier-Regiment lost 51 men (dead, wounded or missing. The Pionierbataillon lost 83 men, and II. Panzerabteilung lost 13 men.

The further course of the battle

The following day the British continued their advance towards Villers-Bocage, resulting in the famous battle of Villers-Bocage on June 13th. The Canadians primarily wenton to the defense. They would see action again during Operation Windsor and Operation Charnwood in early July. These operations were aimed against Carpiquet and Caen, respectively.

Le Mesnil-Patry would eventually be occupied in the night of 16 to 17 June. There was no more resistance by the enemy, since the British had already advanced further on the right flank.

In Mouen on June 17, seven Canadian prisoners of war were brought to the headquarters of the 12. SS Pionierbataillon. After a couple hours of interrogation they were brought to the edge of the village and executed. Six of these soldiers were from the Queen’s Own and one was from the 1st Hussars -- all reported missing on June 11th at Le Mesnil-Patry.

Definitielijst

- Abteilung

- Usually part of a Regiment and consisting of several companies. The smallest unit that could operate independently and maintain itself. In theory an Abteilung comprised 500-1,000 men.

- Brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- D-Day

- The day of the long awaited invasion of western Europe in Normandy, France, 6 June 1944. After a long campaign of deception the allies attacked the coast of Normandy on five beaches to begin their march on Nazi Germany. Often explained as Decision Day, though this is entirely correct. The D stands for Day as generally used in military language. In this case it means an operation beginning on day D at hour H. Hence “Jour J“ in French.

- Heeresgruppe

- The largest German ground formation and was directly subordinate to the OKH. Mainly consisting of a number of “Armeen” with few directly subordinate other units. A Heeresgruppe operated in a large area and could number several 100,000 men.

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- mine

- An object filled with explosives, equipped with detonator which is activated by either remote control or by colliding with the targeted object. Mines are intended to destroy of damage vehicles, aircrafts or vessels, or to injure, kill or otherwise putting staff out of action. It is also possible to deny enemy access of a specific area by laying mines.

- mortar

- Canon that is able to fire its grenades, in a very curved trajectory at short range.

- O-Group

- Order Group, where a commanding officer issues his orders.

- Panzerfaust

- German anti-tank gun used by the infantry. Consists of a long tube with the grenade mounted at the front side. It was a disposable weapon. After being used it cannot be reloaded. Major disadvantage is the long flame back blast from the tube.

- Regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Squadron

- A military unit in the Belgian navy usually six to eight small ships operating together under one command. The smallest military unit in the Dutch air force of about 350 men. In most countries is the designation of a military unit thesize of a company. It is either an independent unit, such as a battery, or part of a bigger Calvary unit. In the air force it is the designation of a unit of aircrafts.

Images

Information

- Article by:

- Jeroen Koppes

- Translated by:

- Thijs de Veen

- Published on:

- 30-05-2021

- Last edit on:

- 30-09-2024

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related themes

Related sights

Related persons

Related books

Sources

- COPP, T., Fields of Fire, University of Toronto Press Inc., Toronto, 2003.

- ELLIS, L.F., Victory in the West, Volume I.

- ELLIS, L.F., Victory in the West, Volume II, H.M. Stationery Office, 1968.

- FOSTER, T., Meeting of Generals.

- GRAVES, D.E., Fighting for Canada Seven Battles: 1758-1945.

- MARTIN, C., Battle Diary.

- MEYER, H., The 12th SS (volume one), Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA, USA, 2005.

- REYNOLDS, M., Steel Inferno, Dell Publishing, New York, 1997.

- STACEY, C.P., The Victory Campaign.

- ZUEHLKE, M., Holding Juno, Douglas & McIntyre, Vancouver, Canada, 2006.