Introduction

Due to the limitations, imposed by the Treaty of Versailles, the number of warships to be constructed in Germany, the Kriegsmarine was far smaller than of her rivals Great Britain and France on the eve of the Second WorldWar.

In order to be on somewhat equal terms with the Royal Navy and the Marine Nationale and to keep the British and French warships away from future German operations, the Germans devised a cunning tactic. As Great Britain was an island empire, she needed to import food and raw materials by sea. The French as well as the British depended on the sea lanes to maintain the economy of their colonies. If German warships could thwart this maritine traffic by attacking and destroying merchantmen, the British and the French would be compelled to deploy large numbers of warships to protect the freighters and to track down the German raiders. Moreover, the Allies stood to lose many valuable vessels and stores in this way.

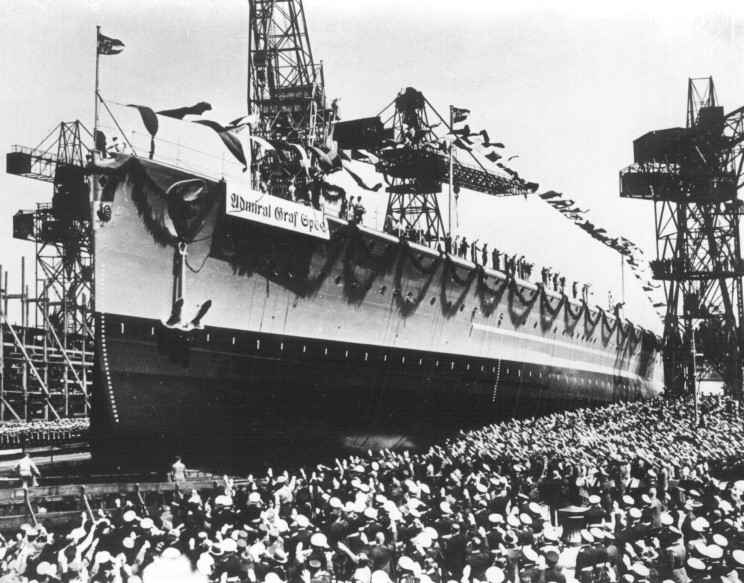

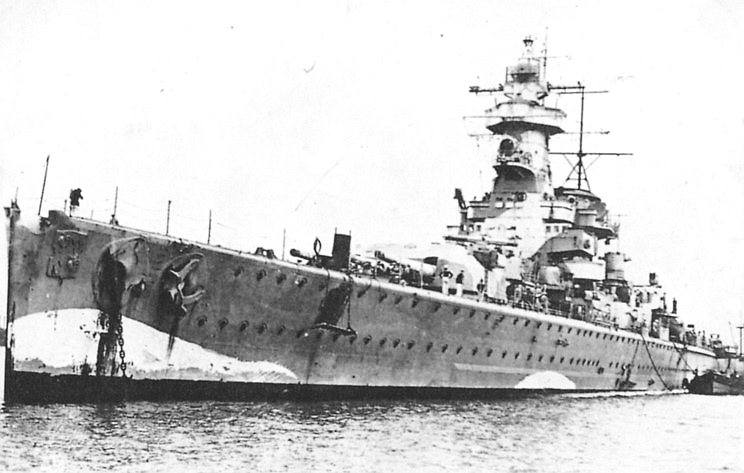

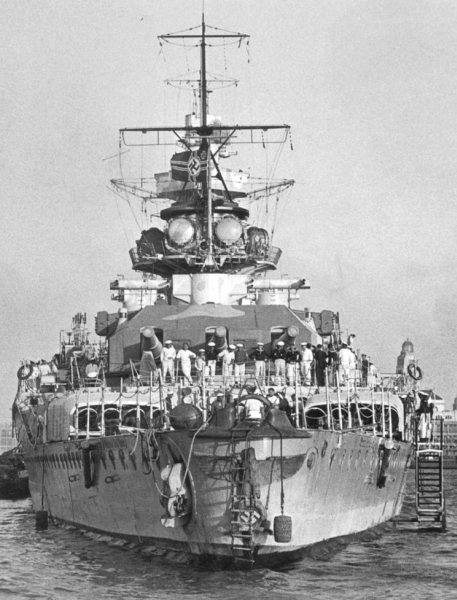

To apply this tactic, the Kriegsmarine had a few dozen U-boats and a number of surface vessels at its disposal. The latter would need a long range in order to operate independently in a large sea area. Only the two battle cruisers Gneisenau and Scharnhorst, the pocket battleships Deutschland (1933), Admiral Graf Spee 1933 and Admiral Scheer, 1934 and the heavy cruisers Blücher and Admiral Hipper met these requirements. All these vessels have been actually deployed as surface raiders. Larger vessels which would enter service later such as the battleships Bismarck and Tirpitz and the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen have been deployed as well to destroy Allied merchantmen.

Pursuant to the Treaty of Versailles, German battleships still to be constructed were limited to a displacement of 10,160 ton and were not to be equipped with guns larger than 28cm. The German response to this were the pocket battleships of the Deutschland class displacing 11,890 ton (the Germans specified only 10,000) with six 28cm guns. The three Panzerschiffe, as they were called by the Germans were, at the time of their commission, better armed and with their maximum speed of 26 knots also faster than any other cruiser of the time. Their light armor, the deployment of the main armament in two triple towers instead of three twin towers and the electrically welded hull instead of using rivets, led to a sharp decrease in weight. The use of Diesel engines gave the vessels a relatively high speed with a considerable range. Later on, the vessels were categorized by the Germans as heavy cruisers but the name pocket battleships, invented by a British journalist in 1930, will last forever. These vessels would prove to be very suitable as surface raiders.

In anticipation of the British and French declaration of war following the invasion of Poland on September 3, the commander of the Kriegsmarine, Admiral Erich Raeder, dispatched the Deutschland and the Admiral Graf Spee into the Atlantic Ocean in August of that year. This way, the two German vessels could already take up position before the British and French could deploy effective patrols. On September 3, the Deutschland was lying in wait in the Denmark Strait whereas Graf Spee was sailing near the Azores on her way to the southern Atlantic to ply her trade as a pirate. The tanker Altmark, which was to supply oil and stores to the raiders frequently was also sent to the Atlantic

Definitielijst

- cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Kriegsmarine

- Germa navy. Part of the Wehrmacht next to Heer and Luftwaffe.

- surface raiders

- Heavily armed and fast merchant vessels, mostly used by the Germans in the early years of both World Wars.

Previous events

As early as September 30, Admiral Graf Spee made her first victim when she sank the British freighter Clement near Pernambuco, northeast of Brazil. The commander of the pocket battleship Kapitän-zur-See Hans Langsdorff, did this in a very honorable fashion. He first made contact with the vessel, allowed the crew to disembark and then sank her. The officers were made prisoner and the rest of the crew was granted the opportunity to get ashore in the life boats. This way, it took a long time before he crew could raise an alarm and this gave Graf Spee ample time to disappear into the vastness of the ocean. Moreover, the imprisoned officers were the only ones who knew the exact posittion where their ship had been sunk. The most important reason however for Langsdorff was: in this way he could spare civilian lives.

The first half of October 1939 was a happy time for Graf Spee Between October 5 and 10, the British merchantmen Newton Beach, Ashlea and Huntsman were sunk off the west coast of Africa. She made her next victim on October 22 near St. Helens: the British freighter Trevanion. Each time, the crew of Graf Spee placed fake name plates on the vessel in order to cause confusion among the Allies who had five squadrons of warships search the Atlantic Ocean since October 5. Moreover, fake gun turrets and funnels, made of wood and canvas, were placed on the ship to alter her silhouette. In order to cause even more confusion among the Allies, Langsdorff decided to try his luck in the Indian Ocean.

On November 1 the Deutschland, having sunk two freighters, was ordered back to Germany. She berthed in Kiel on November 15. Allied warships searched the entire Atlantic Ocean for the two pocket battleships that weren’t there. On the same day the Deutschland arrived safely in Kiel, Graf Spee scored her only success in the Indian Ocean, sinking the small British tanker Africa Shell off the coast of Mozambique near Lorenzo Marques.

His limited success in the Indian Ocean made Langsdorff decide to return to the area between the islands of St. Helens and Ascension in the south Atlantic where he had known better times. Here, the British freighters Doric Star and Tairoa were sunk on December 2 and 3. Three days later, the battleship rendezvoused with Altmark to take on fuel and stores while the supply vessel took a large number of prisoners aboard. On December 7, the pocket battleship scored her last success. The small Streonshalh was sunk 900 miles east of Rio de Janeiro. Of all merchantmen she destroyed, not a single crew member had lost his life. Meanwhile, Graf Spee had covered more than 30,000 nautical miles since her departure from Germany and she was badly in need of maintenance. Langsdorff decided to try his luck in the heavy trafficked mouth of the Rio de la Plata before returning to Germany.

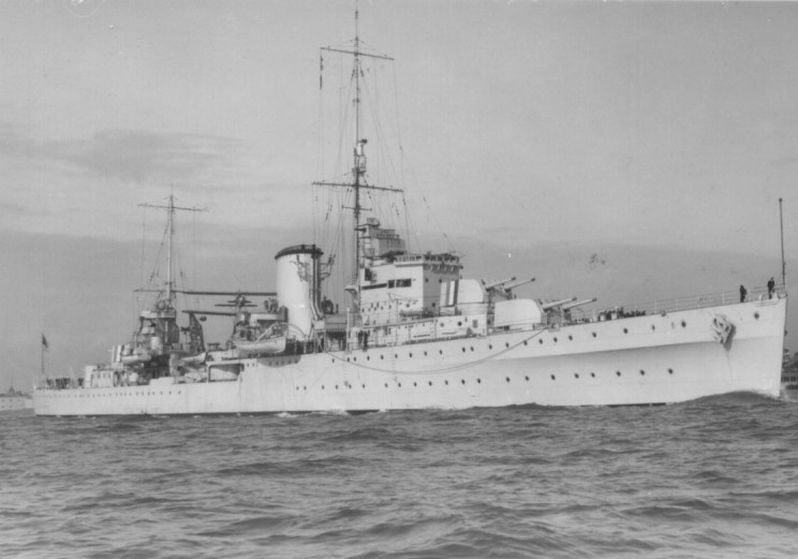

On December 3, the crew of Doric Star had managed to report their position by radio before she was sunk by Graf Spee. The commander of one of the squadrons of Allied warships looking for the pocket battleships, Commodore Harwood therefore decided to assemble his vessels in the mouth of Rio de la Plata. His squadron, the British South-American Division was made up of the heavy cruisers HMS Exeter and Cumberland and the light cruisers HMS Ajax (his flag ship) and the New Zealand cruiser HMS Achilles - at the time, the New Zealand Navy was still a division within the Royal Navy and over two thirds of HMS Achilles’s crew was of New Zealand origin. Harwood had been compelled to dispatch HMS Cumberland to the Falkland Islands for repairs and so, in the morning of December 12, the three remaining Allied warships arrived on the Rio de la Plata.

HMS Exeter was a heavy cruiser of the York class, displacing 8,250 ton and with a main armament of six 8" guns. HMS Cumberland was a heavy cruiser as well but of the County class, displacing 10,400 ton and a main armament of eight 8"guns. HMS Achilles and Ajax were both light cruisers of the Leander class, displacing 7,720 ton and a primary battery consisting of eight 6" guns. Harwood therefore had to make do without his largest and heaviest armed cruiser in the eventual battle against the German raider.

Commodore Harwood called a meeting with his commanders aboard HMS Ajax and presented three possibilities as to where the unknown raider would be. He told them that the first possibility was that the raider would return to the Indian Ocean. He considered this hardly likely as in his opinion, the vessel was in need of maintenance and so it would be farther from home. The second possibility: the raider would take the shortest possible route home. In this case, the other groups of Allied warships would intercept her. The third possibility was that Langsdorff would first try his luck on the Rio de la Plata before returning home. He opted for the third posibility and therefore the three cruisers were now in this area.

Furthermore, the division commander discussed the tactic to be applied in case they would meet the German surface raider: attack immediately and decrease the distance between the enemy and his own ships as soon as possible to gain maximum effect with the lighter guns of the cruisers. In daylight, HMS Exeter would attack from one side and both light cruisers from the other so the enemy would have to face two targets. This was considered too dangerous at night and therefore it was decided to attack in unison. The rest of the day was spent in training for the expected operations against the heavily armed enemy.

Definitielijst

- battleship

- Heavily armoured warship with very heavy artillery.

- cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

- squadron

- A military unit in the Belgian navy usually six to eight small ships operating together under one command. The smallest military unit in the Dutch air force of about 350 men. In most countries is the designation of a military unit thesize of a company. It is either an independent unit, such as a battery, or part of a bigger Calvary unit. In the air force it is the designation of a unit of aircrafts.

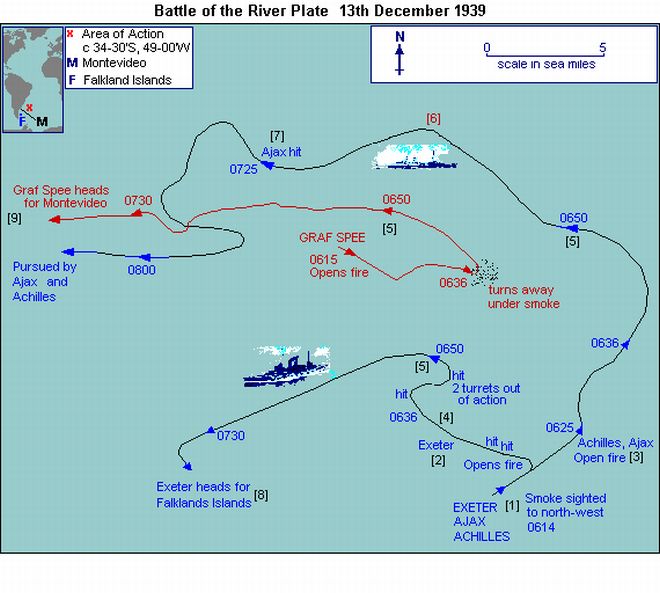

The battle

In the morning of December 13, smoke was observed on the horizon and HMS Exeter was ordered to find out where it came from. At 06:11 the cruiser radioed: "probably a pocket battleship". Graf Spee had observed tops of masts and assuming they belonged to escort vessels of a convoy, the German vessel headed towards the Allied cruisers. When the German raider identified HMS Exeter - one funnel being higher than the other - an engagement was inevitable. At 06:17, Graf Spee opened fire which was answered at 06:20. Both light Allied cruisers approached at full speed to launch a flank attack on the pocket battleship. The battle of Rio de la Plata had begun.

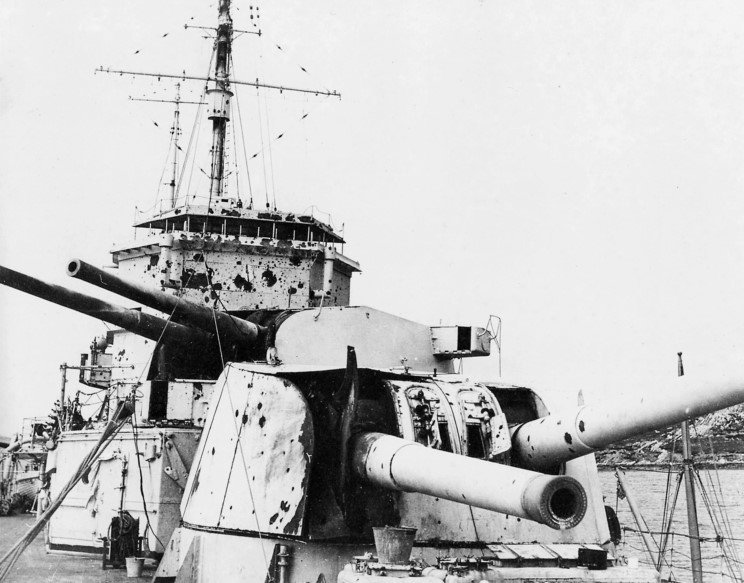

HMS Exeter was hit by various 28cm shells on the fore deck and a few minutes later, HMS Ajax and HMS Achilles opened fire on the German raider with their 15cm guns. Covered by a smoke screen Admiral Graf Spee turned away to escape the fire from the Allied cruisers. Her 28cm guns kept firing though. HMS Exeter received more hits which disabled her forward turrets and struck the bridge. Her commander, Captain F.S. Bell and two others survived the direct hit and for a moment, the ship was out of control. Commander Bell rushed aft to an emergency compass and the emergency steering room was manned. Through a chain of crew members, the commander’s orders were passed on to this position. HMS Exeter was partly operational again and opened fire with her last remaining turret while her last torpedoes were being launched.

The persistence of HMS Exeter granted the light cruisers time to complete their encircling movement and attacked Graf Spee in the flank. They struck with such ferocity that the German vessel had to divert her attention from HMS Exeter and focus on the onrushing light cruisers. HMS Exeter continued firing until power to her last operational turret was cut off by water flooding in. She was compelled to break off the engagement and headed for the Falkland Islands at 07:30 for emergency repairs. Out of her crew, 61 men had died and 22 had been injured by the seven direct hits by 28cm shells and the numerous near misses.

At 07:25, HMS Ajax was hit by two 28cm shells from the German raider, wrecking the [...] gun turret. Aboard the flag ship, seven men were killed and a number of men injured. Commodore Harwood and the commander of HMS Ajax, Captain Woodhouse wanted to withdraw from the battle when it transpired that Graf Spee was unable to direct its gunfire and with a blazing fire amidships was leaving the battle zone. HMS Achilles had been hit by a single 28cm shell and shrapnel from near misses had damaged the director control tower, killing four men. The British commander of the New Zealand cruiser, Captain W.E. Parry had been slightly injured. Both damaged cruisers went into pursuit.

As the day went on, it became clear that Langsdorff was heading for the shelter of a harbor. During the pursuit, Graf Spee repeatedly fired at the two light cruisers but they didn't give up and pursued the German vessel until she dropped anchor at 00:50 on December 14 in the port of Montevideo, Uruguay. Outside territorial waters, the two Allied light cruisers immediately started patrolling the shipping channel in the Rio de la Plata.

Damage to the German vessel wasn't too bad. She had received 15 hits that had destroyed the gunwales and had damaged the bridge. There were a few holes in the deck and in the hull just above the waterline. The largest hole of some 16 square feet was near the bow. In the battle against Harwood’s cruisers, 37 men had been killed and 57 had been injured. In the early morning of December 14, the remaining British prisoners-of-war still aboard, were released.

Definitielijst

- battleship

- Heavily armoured warship with very heavy artillery.

- cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

Diplomatic battle

Montevideo was a neutral port and the Uruguayan government was determined to adhere to the international laws as stipulated in the Convention of The Hague of 1907. An article from this convention prohibits a warship of a nation at war to remain in a neutral port for a maximum of 24 hours. British diplomates in Montevideo, Chargé d’affaires Sir Eugen Millington-Drake and naval attaché Captain Henry McCall, assumed Graf Spee must have been severely damaged, otherwise Langsdorff wouldn't have sought the safe shelter of a port, so they argued. They asked the Uruguayan Secretary of Foreign Affairs, Dr Guani, to send Graf Spee away as soon as possible before the damage could be repaired or else confiscate the vessel and imprison her crew. The French chargé d’affaires in Montevideo, Desmoulins, made a similar request.

Langsdorff received legal assistance from the German Ambassador in Uruguay, Dr Otto Langman and the German Ambassador in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Baron von Thermann (the Argentinian capital is located only 125 miles to the west on the Rio de la Plata. His diplomatic assistants applied for a residency permit for two weeks to repair the damaged pocket battleship. After having consulted the Oberkommando der Marine - OKM - in Berlin, Langsdorff was given three options. The first was an attempt at break out and escaping to Buenos Aires a second. The third was to scuttle the ship. The vessel wasn't to be interned under any circumstance. The Germans were afraid that the Uruguayan government, favorably inclined towards the British, would side with the Allies and then Graf Spee would still fall into enemy hands.

After consultation with London and Commodore Harwood, Millington-Drake and McCall found out that Graf Spee had only suffered minor damage and that the cruisers off Montevideo harbor were worse off. If Admiral Graf Spee was to set sail now, she could probably not be stopped. Therefore they decided to take another route. Publicly, they still advocated the departure of the German vessel as soon as possible but secretly, they expelled the British merchantman Ashwort from the harbor, based on another article in the Convention. This article stipulated that a warship from a nation at war was prohibited to leave a neutral port within 24 hours after an enemy merchantman had done so.

At the same time, the BBC was spinning a propaganda web. They made it known that a large number of British and French warships were heading towards Montevideo to wait for Graf Spee in case she had to leave the harbor. Actually, only the heavy cruiser HMS Cumberland, which had arrived from the Falklands at high speed, joined HMS Ajax and HMS Achilles on December 14. The battlecruiser HMS Renown and the carrier HMS Ark Royal, escorted by the cruiser HMS Shropshire were indeed heading for Uruguay from the north. The heavy cruiser HMS Dorsetshire had set sail from South-Africa as well but none of these vessels was able to reach Montevideo before December 19.

The same night at 20:00, the Germans had managed to get permission to stay another 72 hours in Montevideo for repairs. On December 15, the 37 dead crew members of Graf Spee were buried on the Cementerio del Norte in Montevideo. Langsdorff delivered a short eulogy but he embarrassed the Nazi propagandists by bidding goodbye to his men with the military salute. All other Germans present, including the clergy, gave the Hitler salute.

On December 16, Langsdorff called his most important officers to discuss the situation with them. The three options from the OKM in Berlin were discussed one by one. Langsdorff believed the BBC and assumed that a large Allied fleet was waiting for the pocket battleship off Montevideo. Moreover he was so distraught by the loss of 37 of his men that he didn't want to take the risk to lose even more of his men in an unequal battle. Evasion to the Argentinian capital seemed out of the question to him as well because the German vessel was in great danger of running aground in the shallow shipping channel. It was also very likely the water intakes of the cooling system of the Diesel engines would be clogged by the mud in the river and the vessel would come to a stop. His ship would then be easy prey for the Allies. His officers agreed with him. Hence, there was only one option left: scuttle the vessel themselves. Langsdorff would discuss this with Langman. The German ambassador in Montevideo saw no other way out either.

Millington-Drake meanwhile had ordered another British merchantman to leave port. At 18:15 Dunster Grange left the Uruguayan capital. Admiral Graf Spee was not allowed to leave port before 18:15 on December 17 but was compelled to do so before 20:00 because at that time the residency permit expired.

Definitielijst

- battleship

- Heavily armoured warship with very heavy artillery.

- cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- OKM

- “Oberkommando der Kriegmarine”. German supreme command of the navy

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

The end of Admiral Graf Spee

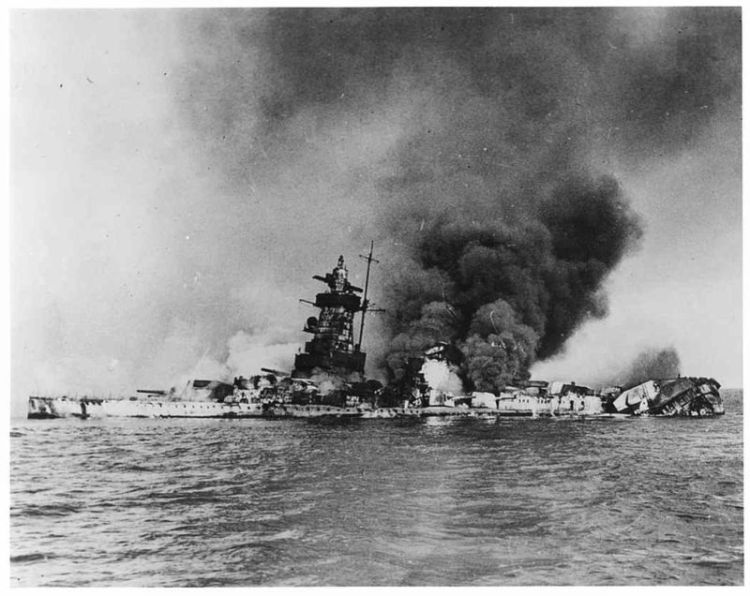

December 17 was entirely spent in making preparations to scuttle Admiral Graf Spee. First, as many secret documents as possible were destroyed and equipment that shouldn't fall into enemy hands was removed. Then the engines were fired up. Finally, the major part of the crew transferred to the German merchantman Tacoma. Only a skeleton crew of 42 and a demolition team remained aboard. They placed charges that would blow up the magazines. It was taken into account that the pocket battleship wouldn't sink very deep and so she would have to be destroyed by the explosions and the fire.

Admiral Graf Spee just before leaving Montevideo, December 17, 1939 Source: Courtesy of Michael W. Pocock.

Langsdorff informed the Montevideo harbor master of his intention to set sail at 18:15. He was allotted a pilot and weighed anchor. Exactly on time, the pocket battleship steamed out of the harbor, watched by tens of thousands. Outside the harbor, the vessel headed for open sea and the pilot left. A few moments later, the German raider suddenly changed course and steamed westwards towards Buenos Aires. She was beached in the mud of the river and dropped one anchor. The charges were armed and the remaining crew members, including Langsdorff, took to the life boats at 20:40 and rowed towards Tacoma which was waiting in the channel. Langsdorff stood rigidly at attention as the charges went off and the magazines blew up. The explosions turned the vessel into a burning and sinking wreck. She soon went down in the shallow river and burned out completely.

Still outside Uruguayan territorial waters, all crew members of Graf Spee boarded two tugs and a trawler sailing under Argentinian flag. The German Ambassador in Buenos Aires, Baron von Thermann, had made the arrangements hoping that the Argentinian government would label them as shipwrecked. On arrival in the Argentinian capital, it transpired however that the Germans were granted the status of military personnel at war and would be interned. The officers were allowed to spend the rest of the war in Buenos Aires itself but the remaining crew members were interned in camps in the interior supervised by local authorities. In practice this meant they had limited freedom of movement and were only obliged to report daily. After the war, many of them settled in Argentina permanently.

Langsdorff was heavily criticized. The local sensation press blamed him for not having gone down with his vessel. Hitler reacted furiously on hearing that Graf Spee had been scuttled by her own crew. He preferred the ship to have gone down in battle. The German commander took all this criticism personally On December 19. 1939 he wrote three letters. One to his wife and a second to his parents. In the third letter to Baron von Thermann he took all responsibility for the loss of his ship upon himself. Subsequently, he committed suicide by shooting himself through the head with his pistol. He was found the next day, wrapped in the flag of the former German Imperial Navy.

Kapitän-zur-See Langsdorff was buried with military honors on the German graveyard in Buenos Aires. Even some officers of British merchantmen who had been sunk by Admiral Graf Spee paid him the last honors.

Definitielijst

- battleship

- Heavily armoured warship with very heavy artillery.

Epilogue

Langsdorff had set an example to German raiders that would be emulated with great success but not as honorable as he had. After his successful campaign, he could have entered into a battle he might have won but he was surprised by the combativeness and determination of Harwood’s cruisers and thrown off balance by the loss of 37 of his crew members. He had walked into the fateful trap of Montevideo himself.

HMS Exeter underwent emergency repairs in Port Stanley on the Falklands and a few weeks later she set sail for England under her own power and unescorted. One cold morning in 1940, the severely damaged cruiser entered the port of Plymouth in southern England where the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill was waiting for her. During a speech, attended by the entire crew, the future British war leader voiced his admiration of the role the heavy cruiser had played in the battle on the Rio de la Plata. HMS Exeter spent 13 months in dock for reparation and modernizing. One year later, on March 1, 1942 the British vessel was sunk by Japanese cruisers in the Sea of Java.

HMS Ajax was repaired on Malta and during the war, she saw action mainly in the Mediterranean where she was damaged frequently by German and Italian aerial bombs. In Ontario, Canada a new city of Ajax was baptized after the successful battle at Rio de la Plata and many streets were named after crew members of Harwood’s cruisers. The ship was torn down in 1949 in Newport, Rhode Island, USA. The same year, one of the ship’s bells was donated to the city of Montevideo and presented by Admiral Sir Henry Harwood and Sir Eugen Millington-Drake.

After the Battle of Rio de la Plata, HMS Cumberland left for Simonstown near Cape Town in South-Africa and later on, she was mainly deployed to protect the arctic convoys to and from Russia. In the last year of the war, the vessel saw action in the Far East. After the war the heavy cruiser was modernized again and her entire armament was replaced. The Suez crisis in 1956 was the last conflict in which she was deployed, mainly transporting troops to Cyprus. In 1959, the vessel was torn down in Newport, Rhode Island.

HMS Achilles actually would be sent to Malta for repairs as well, but the British Admiralty complied with a request by the New Zealand government to send the vessel to Auckland. The Leander class cruiser was received by military parades in Auckland and in Wellington, the capital of New Zealand.

Owing to the important role of HMS Achilles had played during the Battle of Rio de la Plata, the New Zealanders gained greater affinity with the navy. On March 31, 1941, the Royal New Zealand Navy - RNZN - was established and HMS Achilles was renamed HMNZS Achilles. Towards the end of the war, the New Zealand Navy numbered over 10,000 men, predominantly serving aboard British vessels. The light cruiser remained in Auckland until June 1940 where she was repaired and modernized. Thereafter, she mainly saw action in the Pacific. After the war, the vessel was returned to the Royal Navy. In 1948, HMS Achilles was sold to India and commissioned as INS Delhi. The vessel was torn down in Bombay, India as late as 1978. One of her gun turrets was donated to New Zealand and now stands as a memorial on Devonport Naval Base in Auckland.

Definitielijst

- cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

Information

- Article by:

- Peter Kimenai

- Translated by:

- Arnold Palthe

- Published on:

- 04-12-2022

- Feedback?

- Send it!