Introduction

As early as 1942, the Allies had been drafting plans for a possible invasion of the continent of Europe. After lengthy consultations between high ranking military and a critical search for a suitable landing site, Normandy was selected eventually. The area offered advantages as most beaches were readily accessible to men as well as to heavy equipment. The relatively weak defense of the Germans in the area would offer sufficient opportunities for the Allies to occupy the beaches quickly and push inland.

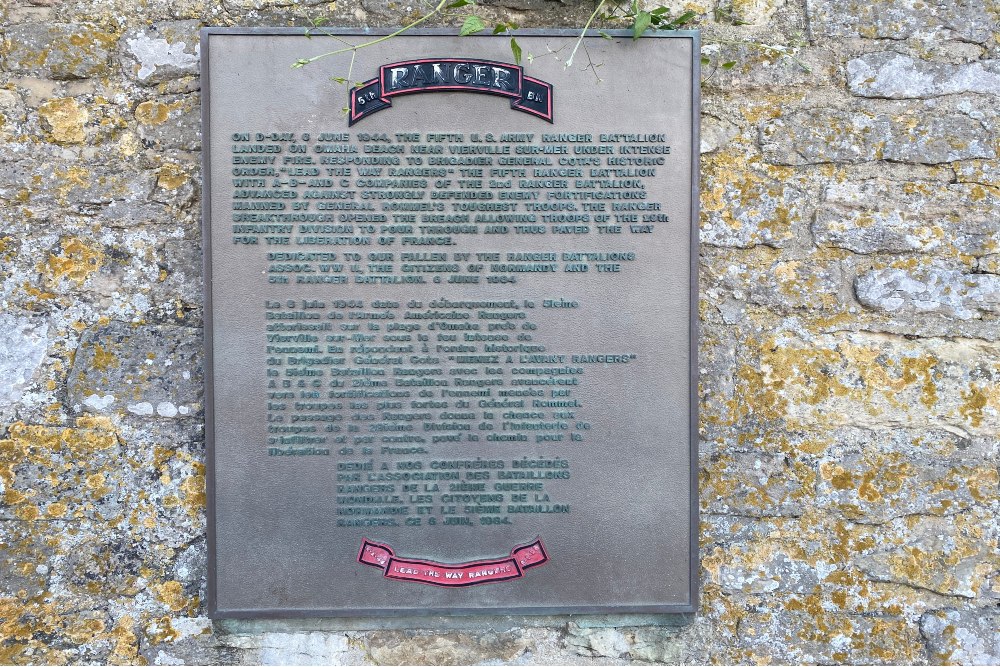

Five beaches were selected and given code names. The British would go ashore on Sword Beach and Gold Beach, the Canadians on Juno Beach and the Americans on Utah Beach and Omaha Beach. Further inland, special troops would be dropped to establish bridgeheads between the various beaches.

Between Utah and Omaha, assigned to the Americans, a steep cliff rose over 100 feet above the water: Pointe du Hoc. The extensive reconnaissance flights over Normandy, prior to the invasion, had produced a number of photographs revealing six heavy guns. After investigation, they turned out to be 155mm howitzers with a range of 15 miles. These would enable the German defenders to subject the Allied units landing on Utah and Omaha to heavy fire. Moreover, they enabled the Germans to strike at the Allied vessels off the coast.

Disabling the batteries on Pointe du Hoc was therefore inevitable. Not only the success of the American infantry units on Omaha and Utah would depend on the results achieved on Pointe du Hoc, the rest of the invasion plan also relied on the elimination of the heavy howitzers. The question however was how this could be achieved as the 100 feet cliff was considered an immensely difficult obstacle.

Preparation

General Dwight Eisenhower, Commander-in-chief of the Western Allies in Europe, and his chiefs of staff decided to have the operation executed by an elite unit, trained just for that kind of attacks: the 2nd and 5th Ranger Battalion, commanded by Lieutenant-colonel James Earl Rudder.

Rudder was born May 6, 1910 in Eden, Texas. After having taken an agricultural course from 1928 to 1929, in 1930 he attended Texas A&M University, achieving a degree in Industrial Education in 1932. After graduation he was appointed 2nd Lieutenant in the infantry of the American reserve. From 1933 he was employed as football coach and teacher at Brady High School. In 1941 he entered active service.

Over 2,000 US military had applied to join the Rangers. Lieutenant-colonel Rudder selected 500 of them and trained them specifically for their difficult assignment.

The Rangers trained in the hot and humid atmosphere of Tennessee. This made this physical exertion heavier. They made marches of 50 miles, many cross country and speed marches and they trained for hours to use explosives.

Rudder demanded much of his men. He knew like no one else how the success of the operation depended on the persistence and discipline of the Rangers. One day, when they were asleep during a transport, Rudder had the train stopped, woke up his men and had them leave the train. In the midst of a heavily forested area, they were to live off the land for a few days. His intention was to impress his men with the importance of being able to survive with a minimum of resources.

Once the Rangers had been transferred to Great Britain, Rudder sent two of his most intelligent and reliable men - Staff Sergeant Jack Kuhn and Private first class Peter Korpalo - to a company in London named Merryweather. There they would have to contribute to the development of a better way to scale the cliff than with conventional climbing ropes. They soon found a solution: during the landing the Rangers would use extendable 115 feet firefighting ladders.

The German 352. Infanterie-Division was stationed on the other side of the Channel. This unit had been established in November 1943 and was commanded by Generalleutnant Dietrich Kraiß. Although it was a fairly new unit, it consisted of a relatively large number of veterans. It defended the positions on Omaha Beach as well as on Pointe du Hoc. In contrast to many other German divisions stationed in Normandy, the 352 was still at full strength. As a result of a reorganization, most German divisions lost one battalion of each regiment on average. The 352 did not however. This division was to cause considerable damage on Omaha Beach.

Eventually the time came for the company commanders to brief their men about the upcoming operation. The leaders emphasized the great danger which would undoubtedly prevail during the operation. In their opinion, every soldier getting near the cliff unharmed would deserve a medal. By the way, a decree from Adolf Hitler, the notorious Kommissarbefehl, ordered the Wehrmacht to treat every Allied soldier, identified as Commando or Ranger, not as a prisoner-of-war but as a spy to be executed on the spot.

Rudder had selected D, E and F Company of 2nd Ranger Battalion to climb the cliff and lead the main attack. Their specific task was to disable the howitzers, C Company would land alongside 116th Infantry Regiment in sector Charlie on Omaha Beach. A and B Company would land on Pointe du Hoc at 07:30 where they would receive a message to the effect that Rudder needed them there; if not, they would land on Omaha Beach, just like C Company. The 5th Ranger Battalion would wait, just like A and B Company of the 2nd Ranger Battalion, in the landing craft until they received the message that the attack on the guns had been successful. Only then would these reinforcements climb the cliff. If the signal hadn't been passed on within 30 minutes of the initial attack, these men would land on Omaha Beach and in a surrounding movement overpower the German defenders on Pointe du Hoc from the rear.

D, E and F Company would be commanded by Lieutenant-colonel Cleveland A. Lytle. During one of the last briefings, he learned however that the Free French had reported that the guns that were supposed to be on the cliff had been removed in the meantime. During a fierce argument with his superiors, including Lieutenant-colonel Rudder, he called the attack ‘unnecessary’ and ‘suicidal’. Consequently, Rudder thought Lytle would be unable to lead the attack in a convincing manner so Rudder decided to take charge of D, E and F Company himself. Lytle was transferred to the 90th Infantry Division and was later awarded the DSC for his actions.

The tactical plan of attack required correct timing. The American Air Force was to fly over the cliff at a preset time and drop their bombs - whether Rangers were present or not - if the German guns would still fire 30 minutes after the devastating bombardment by the Allies.

When after a postponement of a day, Eisenhower ordered Operation Overlord, the Allied invasion of Normandy, to be launched in the early morning of June 6, the Rangers boarded HMS Ben-My-Chree. The vessel joined the enormous armada off the Isle of Wight. In the early morning of June 6, Rudder’s 225 men who would launch the initial attack, were treated to a luxurious breakfast. They carried as little gear as possible. Only four BAR’s would be carried along and no more than two 60mm mortars per company. A little before 04:00, the rangers boarded their LCA’s. They made two columns of 6 craft each that raced across the wild sea that was still rough from a violent storm of the day before. Ten out of the twelve craft transported the men, the other two carried equipment. They were accompanied by four DUKWs to which the ladders were attached. Each DUKW was equipped with two Vickers K machineguns which would offer additional protection during the expected difficult landing.

Execution

In the early morning of June 6, the 10 landing craft set off from HMS Ben-My-Chree and headed for the landing site. Due to navigational problems and bad weather, there was a delay of 40 minutes and one craft went down in the rough sea. Only one Ranger survived. Shortly after, another craft capsized, putting the commander of D Company and his 20 men out of action. Soon the Rangers were compelled to scoop out the water that was coming in by the heavy surf with their helmets. For another craft, carrying rations and ammunition it was too late, it went down close to shore, killing five crew members. One DUKW didn't make it to shore either.

While the Rangers steadily approached their targets, for 35 minutes the dull explosions of the shells from USS Texas could be heard on the top of the cliff further inland. The delay had partly been caused by navigational problems as the craft were heading towards the eastern side of the cliff. Rudder recognized the problem and had his mates adapt their course. The German defense at the foot of the cliff was relatively weak until the craft were about a mile away. The Germans treated them to machinegun and mortar fire. Eventually, the Rangers went ashore at 07:10 and only half of the original 225 men made it. E and F Company occupied the eastern side of the beach whilst D Company would see to the western side.

While the Rangers were positioning their firefighting ladders, they were continuously subjected to a barrage of German fire on their left flank and 15 Rangers were hit. Gene E. Elder, Ranger of 2nd Ranger Battalion vividly remembers the landing: ‘We found out that the cliff was higher than the one we climbed in Cornwall. This one was about 130 feet high.’ The ladders reached to about 108 feet. As soon as he had come ashore, Rudder sent the signal ‘tilt’, meaning that the reserves waiting in their landing craft in the Channel were to land on Omaha Beach and fight their way inland.

Shortly after, the Rangers had to seek shelter against a rain of grenades dropped from the top of the cliff. From the Channel, the destroyer USS Satterlee saw Rudder’s Rangers fighting the Germans without adequate covering fire. Her captain steered towards the beach at the foot of the cliff, opening fire on the Germans who held an excellent firing position on the top. Soon, the Germans drew back, spreading out as well and finally enabling the Rangers to start climbing the cliff. Each of the landing craft was equipped with three pairs of rocket launchers firing anchors with ropes attached to the top of the cliff. Climbing ropes and rope ladders could be attached to these. Some craft experienced trouble firing their anchors by launching them too early or because the ropes were too heavy to fire them 130 feet up. Other anchors did reach the top but they didn't hold. In the end, all but one craft managed to reach their goal. In some cases, Germans were cutting the ropes. Despite the delays, success was achieved because now there were sufficient ropes and rope ladders attached to the cliff to enable the Rangers to climb up.

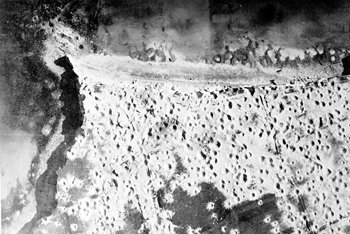

The bombs of the Allied warships and aircraft had broken off chunks of clay and slate, soon making the first 10 feet passable without ropes. Within five minutes after landing, the first Rangers had already made their way to the top. In groups of three or four they went after their pre-designated targets, destroying the howitzers. Some Rangers, drenched with muddy water after having fallen in water filled craters on the beach, had trouble climbing. Not only they were wet themselves, the ropes were also soaking wet. Half an hour after the initial landing, all Rangers eventually managed to scale the cliff. They entered into a no man’s land dotted with gigantic craters, making mutual contact very difficult.

The aerail bombardment also caused severe damage to the cliff, enabling the Rangers to scale the better part without ropes Source: US Army.

Only a few Germans were observed initially but they soon disappeared in the intricate network of trenches. The Rangers soon found out that the radios they had dragged up didn't function properly. Rudder ordered his liaison officer, James ‘Ike’ Eikner, to go down again, find a working radio and send the message ‘Praise the Lord’ to HQ, indicating that the first part of the landing had been successful. The message would reach the other troops too late though.

After the landing

At 06:40, A Company of the 116th Infantry Regiment came ashore in sector Charlie on Omaha Beach. A few minutes later C Company followed and landed in an entirely isolated position; the nearest American soldiers were over 1,5 miles away. Violent fighting erupted for both companies and the Americans suffered heavy losses. A Company was left with hardly any manpower while Company mourned the losses of 19 dead and 18 injured. With just 31 men, C Company had to attempt to push through from Omaha Beach to Pointe du Hoc.

Shortly after the landing on Pointe du Hoc, Rudder established his HQ in a deep crater on the edge of the cliff. Because of the initial communication problems however, when the message of the success couldn't be passed on in time his reserve troops, A and B Company of 2nd Ranger Battalion had landed anyway at 07:40 on chaotic and hellish Omaha Beach. Soon these men were drawn into the intensive fighting raging there. Hence, they were unable to push further inland, let alone reach Pointe du Hoc. They did however play a crucial role in capturing German fortifications and defensive positions.

Despite the Rangers being inferior in numbers in many sectors on Pointe du Hoc, they managed to capture more and more ground. About 07:45, the German defenders launched a counterattack through the trenches, overpowering the Rangers and taking them all prisoner, except one. He managed to rush to HQ, some 100 yards away where nothing had been heard yet about the German attack. A counterattack was improvised quickly and 12 riflemen and a mortar team were deployed. They soon encountered heavy artillery fire that killed or injured almost every member of the assault team.

The navy and the air force made a considerable contribution to the successes achieved on Pointe du Hoc by their precision shelling and bombing. USS Satterlee and HMS Talybont fired all day to lend adequate fire support to the Rangers. In this they succeeded; USS Satterlee for instance was largely able to repel German counterattacks, enabling Rudder and his men to occupy more terrain gradually.

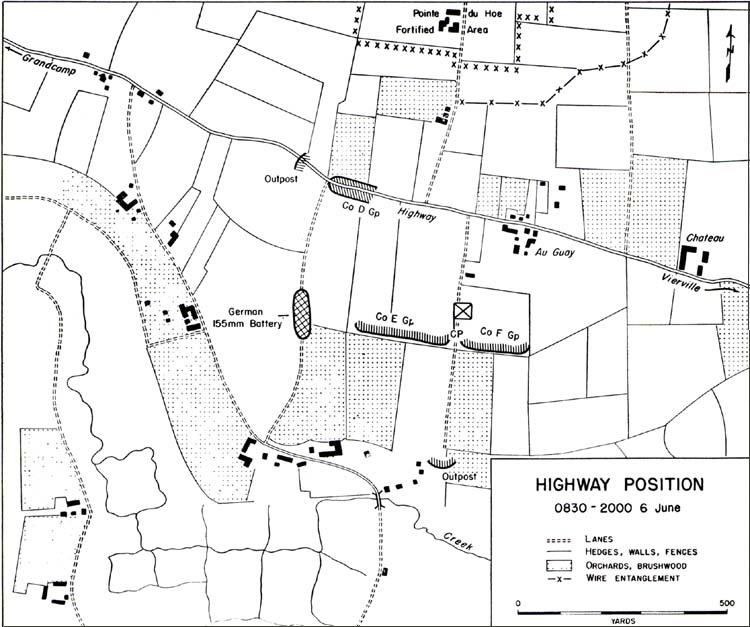

The Germans had a fitting answer to this though. From Maisy, some 3 miles from Pointe du Hoc, they unleashed a long and continuous artillery barrage on Rudder’s advancing troops. About this time, Rudder himself was injured by a sniper bullet passing through his shoulder. He decided not to transfer command and would remain commander of the unit throughout the rest of the mission. After many engagements, with huge numbers of losses on both sides, the Rangers finally managed to fight their way to the six howitzers. Three of them turned out to be still under construction. The other three gun mounts were empty because the Germans hadn't installed the guns yet. As the Rangers were unable to complete their primary task, they turned to their secondary task: erecting a roadblock on the coastal road. They were to establish a defensive position between Vierville-sur-Mer and Grandchamp-Maisy and wait for the 116th Infantry Regiment to arrive.

D, E and F Company of 2nd Ranger Battalion managed to force the German to retreat just before 08:00. The Germans now formed a firing line in the path of Rudder’s exhausted men, plastering them for two hours. In the evening, the Germans launched five counterattacks, hoping to disperse the Americans. In this they failed however and during the morning, the Rangers set foot on the coastal road that was to be a key position for the further success of the Allied invasion. In the process, a German sniper managed to kill six Rangers before he eventually revealed his position and was killed himself.

In the morning of June 7, all company commanders had been put out of action due to heavy fighting. Each company was now short of many men. The three new commanders decided to establish a defensive line along the coastal road where they could greet the infantry arriving from Omaha.

In the early morning, the Rangers managed to disrupt the German communication lines. The defenders responded by launching an attack on the positions of the Rangers along the coastal road. After a short exchange of fire, the Germans were driven off. About 08:30, when the Rangers were patrolling the road, they saw the 155mm howitzers at about 100 yards from their own line. A massive amount of ammunition consisting of heavy shells was found near the guns. The guns stood at some 500 yards from the empty mounts on the cliff where they should have been, according to the aerial photographs. Due to the near perfect camouflage, they were impossible to identify in the pictures.

Sergeant Leonard Lomell, his platoon commander 2nd Lieutenant George F. Kerchner and Staff Sergeant Jack Kuhn ran towards one of the guns to disable it with two thermite grenades. These grenades made the swivel mechanism melt, disabling the guns. The Rangers rushed back to their lines to get the remaining grenades to disable the other guns. This was followed by a massive explosion for which Sergeant Rupinski and his team of E Company were responsible.

After having disabled the guns and captured Pointe du Hoc in the early morning of June 6, the Rangers prepare for a counterattack Source: US Army

While the news spread that the mission had been accomplished, the Rangers took up strategic positions to repel an eventual counterattack. At 09:00, all howitzers were out of action, the connection of the Germans via the coastal road was severed and a roadblock had been established.

Holding out

In the afternoon of June 6, the rest was shattered by some sporadic exchanges of fire. The Germans attacked from the south and west to recapture their lost positions. During the first attack at 14:30, the Rangers suffered no losses. They managed to respond adequately to the German fire that gradually weakened. At 16:00, a second counterattack was launched, this time causing more danger to the Rangers. Their weakest positions were attacked by heavier fire than before: this time with machineguns and mortars as well. Only when the Rangers managed to mobilize more men and heavier fire power, they succeeded in pushing the Germans back. Until nightfall, enemy activity could be observed but this didn't evolve into a coordinated attack.

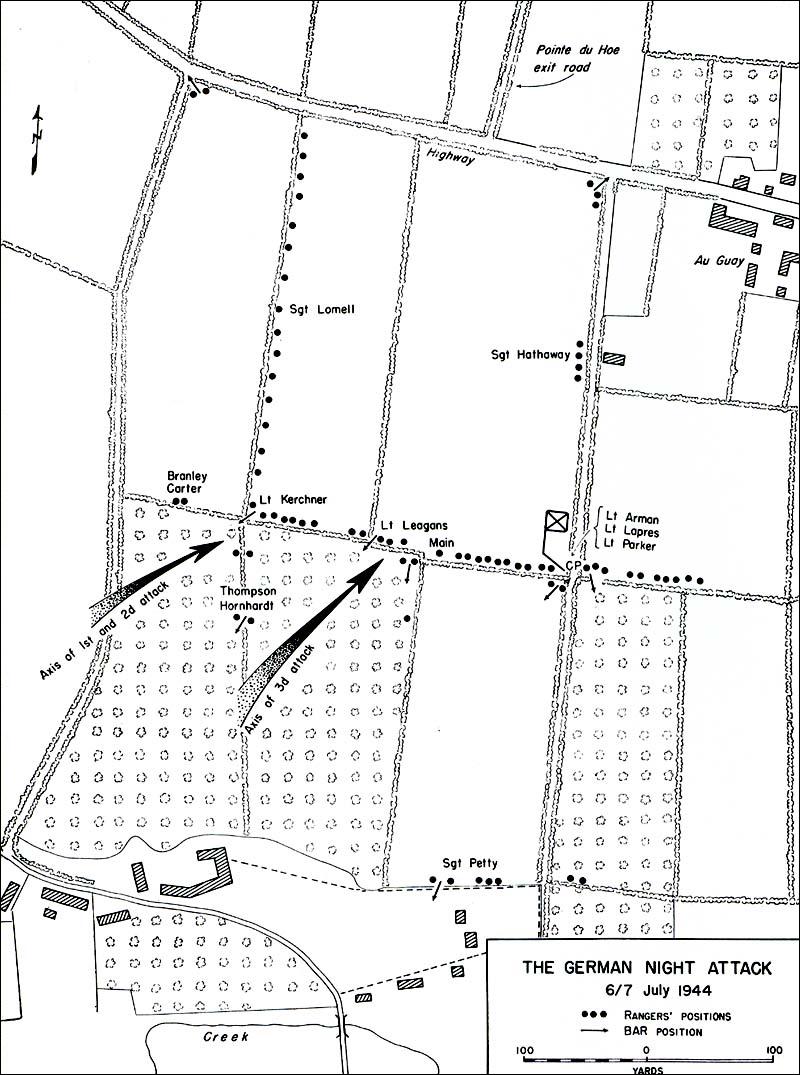

As the night of June 6 to 7 approached, Rudder faced a dilemma. He had to disperse his battalion, usable only to a limited extent, over a wide area. Many ‘deployable’ men including himself had been lightly injured during the first day. Nonetheless, the Pointe and the coastal road to Grandchamps-Maisy had to be held. Possibly, an attempt should be made as well to disable the anti-aircraft batteries further inland. The Rangers had to cope with a shortage of ammunition, in particular hand and mortar grenades.

Rudder decided to hold the road blockade and not to shorten the perimeter. He was actually still waiting for 5th Ranger Battalion and 116th Infantry Regiment from Omaha Beach. He wasn’t worried about the loss of that position as the Germans had already launched a number of counterattacks on the blockade, achieving not a single success yet. He was worried though about the German artillery further away which could possibly inflict damage on the Rangers. By extending the perimeter over a larger area he hoped to avoid damage by bombardments.

Towards midnight there was a serious shortage of ammunition, in particular shells for the semi-automatic weapons. Hand and mortar grenades could only be used very sparingly. The Germans attacked again between 23:00 and 00:30 but once again their attacks were uncoordinated. Hardly making use of fire support by mortars, they attacked the dug-in positions of the Rangers in small groups. The attacks weakened when it became clear that the Rangers could hold out relatively easy although this took considerably more trouble than during the afternoon.

From 01:00 on, the Germans increased the speed and intensity of the fire fights. They mainly attacked from the south and southwest where the high shrubs offered a near perfect camouflage for their advance. Earlier that day, this tactic had proved successful but this time they met stronger resistance from the Rangers. The Germans did deploy machineguns and mortars and plastered the weakly defended positions of the Rangers with grenades before throwing themselves into battle. Accompanied by the shrill German whistles (used to lead the attack) a chaotic skirmish unfolded in which both parties literally fired at will. During that fight, the Rangers were ordered not to fire at random anymore as from then on, every bullet was valuable.

At 03:00, the third German attack was launched. This proceeded somewhat like the second. Accompanied by the same whistling, fire was heavy but inaccurate. In particular, their mortar fire came down on the position where the Rangers kept their prisoners-of-war. This time however, the German managed to push through further to the east near Rudder’s HQ. E Company’s perimeter was penetrated here. An intense fire fight erupted during which almost 40 Rangers were killed. The 20 survivors were taken prisoner and marched to a command post a mile away. The men of the other companies soon found out that E Company had been defeated as German fire came from their former positions. This caused the decision to retreat. The command post was evacuated as well. The Germans now managed to pass through the shrubs and gradually surround the Rangers in a pincer movement.

At about 04:00, 50 Rangers joined those already on Pointe du Hoc. They entrenched themselves in an improvised defensive position. Before sunrise, they could do little to improve their defense. At that moment, Rudder learned that E Company had been ‘destroyed’ although neutralized would have been a better term. D Company had met almost the same fate but they could hold out partially and at that moment was widely dispersed along the coastal road. During the last battle, when the main body of the Rangers retreated, they had been compelled not to join the fight as they found themselves in an extremely vulnerable situation.

Next morning, the survivors of D Company remained motionless among the shrubs. The Germans didn't start a search for them. The main worry of the survivors was the friendly fire from the navy. The shells came down close to them but didn't cause any dead or wounded. At the end of the afternoon, luck finally seemed to be on their side: four Sherman tanks rumbled along the road but were not followed by infantry. Shortly after, the tanks disappeared again. At that moment, the Germans returned to set up machineguns along the road and so, the Rangers prepared to spend another night in the bushes.

On June 8 success on Pointe du Hoc had finally been achieved: German prisoners-of-war are being taken away Source: NARA

Meanwhile, June 6 had passed and Rudder’s unit numbered less than 90 deployable Rangers out of the original 225 (excluding reserve troops landing on Omaha Beach as only a few managed to get through the obstacles around Pointe du Hoc). They had now been surrounded in a pincer movement and had been forced to give up much of the ground gained. Spread across a number of acres, in a badly defended position they were easy target for the merciless shelling from enemy artillery and subsequent attacks by infantry. During the next days, this would not unfold in the same intensity as in the hours before.

With the artillery support from the battleships at sea (including USS Texas, the Rangers managed to hold. In the afternoon of June 7, their situation improved a little when an additional platoon carrying stores and ammunition landed at the Pointe. Towards midnight the Rangers made contact with a patrol from St. Pierre-du-Mont, just a mile away from their own position. In the course of the next morning, 5th Ranger Battalion and 116th Infantry Regiment joined the other Rangers, making the success of Pointe du Hoc definite.

Epilogue

The successful attack on Pointe du Hoc is still considered a military operation exceeding the usual. Even years after the attack, the Rangers still wondered how they had done it. Under heavy enemy fire and by using soaking wet ropes they managed to climb a cliff of nearly 130 feet and subsequently capture the surrounding area. The Rangers completed the most difficult tasks under the harshest conditions

Chaplain Joseph Lacy for instance had landed along with the other troops under heavy fire and all day long he pulled the injured out of the water, took care of them on the beach and delivered the last sacraments if needed. Later on, he would be rewarded the DSC for this, the second highest US military decoration. Sergeant Lomell and his platoon commander, 2nd Lieutenant George F. Kerchner were also decorated with this medal for their contribution in disabling the howitzers. For his role in this, Staff Sergeant Jack Kuhn was awarded the Silver Star. Rudder was also rewarded the DSC for his exceptionally courageous conduct, leadership and correct decisions despite the fact that in the end, he had been injured three times. Later on, all Rangers were to receive a Presidential Unit Citation.

Speech by President Ronald Raegan (1984) in memory of the attack on Pointe du Hoc, 40 years ago Source: Reagan Library

Once rest had returned to Pointe du Hoc, the balance could be made up. Out of the 225 men who participated in the landing, 35 were injured and 80 were killed. In the hours after the demolition of the howitzers, the Rangers had been compelled to hold out with just 90 men. The reserve troops landing on Omaha Beach, because a signal couldn’t be sent in time from the Pointe, suffered heavy losses as well. A and B Company lost almost half of their strength while C Company lost 38 men out of the 64.

Despite the fact that no guns were found on Pointe du Hoc itself, the importance of the success can't be denied. The guns, located further inland, could have inflicted severe damage on Utah and Omaha Beaches. Not only the Americans would have encountered problems but the British and Canadians as well. In that case, the last two would have had to cope with far more concentrated opposition from German side and the British and Canadian invasion could possibly have turned into a stalemate. The capture of Pointe du Hoc was crucial in the end.

Information

- Article by:

- Bob Erinkveld

- Translated by:

- Arnold Palthe

- Published on:

- 13-12-2022

- Last edit on:

- 30-09-2024

- Feedback?

- Send it!