Introduction

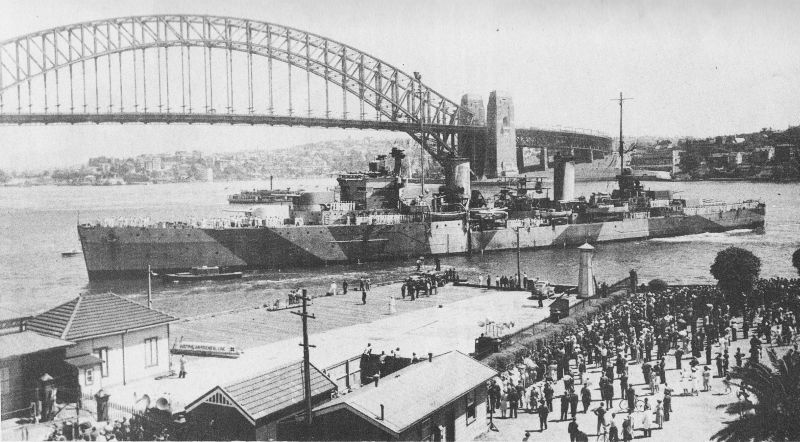

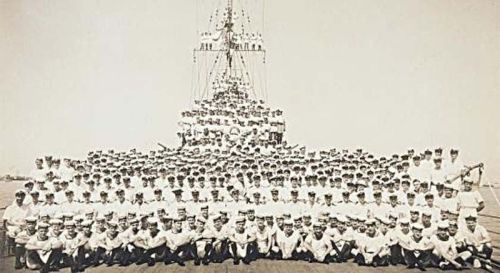

HMAS Sydney was a Leander class light cruiser of the Royal Australian Navy (RAN). Her keel was laid on the Swan & Wigham Richardson Ltd. shipyard in Wallsend-on Tyne on July 8, 1933. Construction was ordered by the Royal Navy and she was to be baptized HMS Phaeton. The Australian government bought the vessel - still under construction - in 1934. On September 22, 1934, the cruiser was launched and a year later, on September 24, 1935, she was commissioned by the RAN as HMAS Sydney, in memory of the former cruiser with the same name. She was armed with eight 6" and four 4" guns; twelve 0,5" Vickers and nine 0,3" machineguns and eight 21" torpedo tubes. She was propelled by four Admiralty steam boilers and Parsons geared turbines, delivering 70,000hp and with her four propellors could steam at a maximum speed of 32,5 knots.

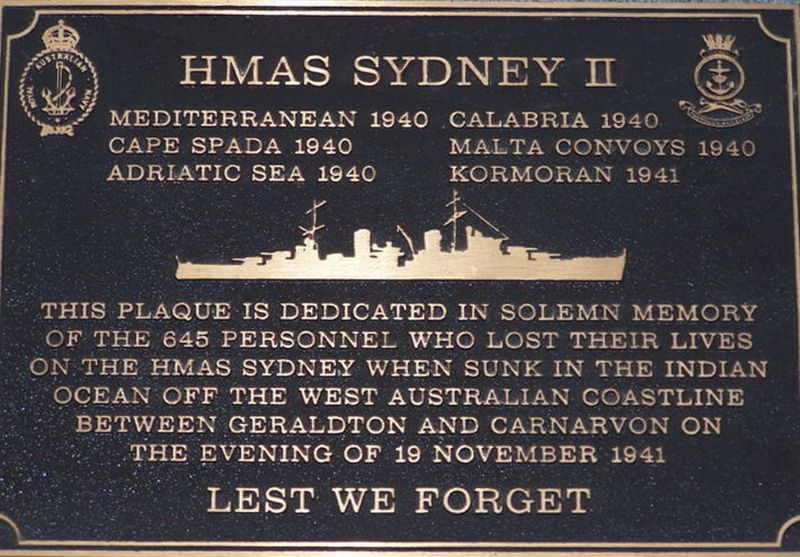

In May 1940, the cruiser was posted to the British Mediterranean Fleet for a period of eight months. During this time, she sank two Italian warships, participated in shore bombardments and escorted Allied convoys on their way to Malta. Since her return to Australia in February 1941, she made escort trips and patrols in her home waters.

In October 1941, she was berthed in Fremantle, western Australia, waiting for the transport vessel Zealandia This Australian vessel, carrying troops to Malaya, would be escorted by HMAS Sydney part of the way. As late as November 11, both vessels left the port of Fremantle. The cruiser escorted the troop carrier to the Sunda Strait, between the Indonesian islands of Java and Sumatra where she was relieved by the British light cruiser HMS Durban. Subsequently, she radioed she would be back in Fremantle on the 19th, possibly the 20th. Later on, in a second message, she radioed in it would be the 20th definitely. This was the last message ever received from HMAS Sydney

Definitielijst

- cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

HMAS Sydney reported missing

When on the 23rd HMAS Sydney had still not arrived in Fremantle, Australian aircraft were sent out to search all day for the missing cruiser but found nothing. Regarding the seriousness of the situation, the RAN took measures. The naval commander in the Dutch East Indies, Admiraal Conrad Helfrich was asked to search for the cruiser south of Java and he dispatched Hr Ms Tromp.

The Australian navy leadership meanwhile assumed HMS Sydney had fallen victim to the German auxiliary cruiser Source: http://www.naa.gov.au

Less than two hours after the message to the admiral was sent, the British tanker Trocas reported she had picked up a raft with 25 German navy personnel some 120 miles west northwest of Carnarvon on the west coast of Australia. Merchantmen in the vicinity of Trocas' position were ordered to look for survivors. In addition, four auxiliary RAN vessels, HMAS Yandra, Heros, Olive and Wyrallah were sent to the designated area as well as reconnaissance aircraft. As Hr Ms Tromp was searching north of this area, vessels were looking for HMAS Sydney over a vast area of ocean.

The Dutch light cruiser Hr. Ms Tromp participated in the search for missing HMAS Sydney Source: Peter Kimenai Go2War2

From November 24 onwards, five vessels picked up more survivors from the Kormoran while two life boats with 130 men had managed to reach the Australian coast.

Based on the information of 300 of Kormoran's crew members, including the commander, it was possible to make a report of the events.

Definitielijst

- cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

German Handelsstörkreuzer Kormoran

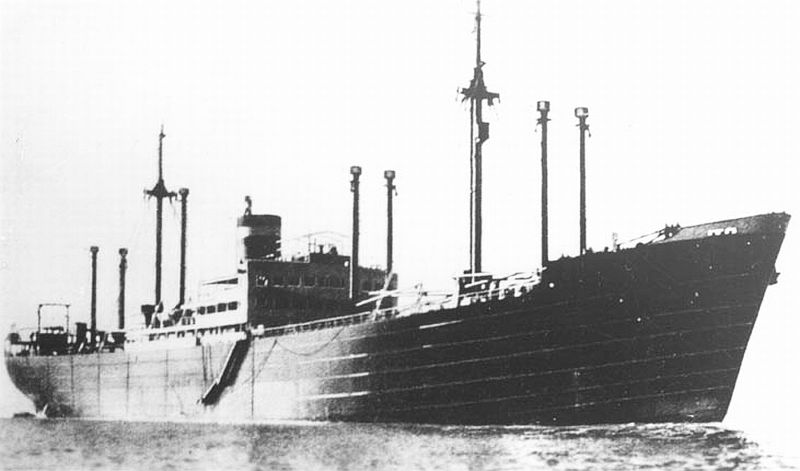

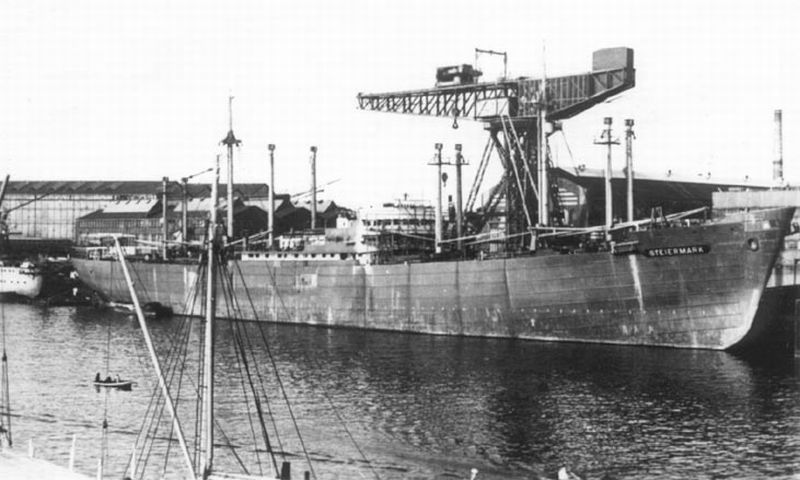

The auxiliary cruiser Kormoran or Schiff 41, her codename, was the largest and fastest cruiser of the Kriegsmarine in the Second World War. Initially, motor vessel Steiermark of the Hamburg Amerikanische Paketfahrt (HAPAG), this vessel of 8,736 ton and launched in 1938, was converted in the course of 1940 into an auxiliary cruiser. On October 9 that year, she was commissioned by her commander Korvettenkapitän Theodor A. G. Detmers.

The Germans called the vessel Handelsstörkreuzer or HSK Kormoran The vessel was a fine example of a successful disguise of a merchantman to a battleship, which were in use by the Kriegsmarine during the Second World war. Kormoran was heavily armed with six 15cm guns, hidden behind folding bulkheads, four 37mm guns. five 20mm machineguns, six 53,3cm torpedo tubes, 360 mines and two Arado Ar-196 A-1 float planes. Nonetheless, the vessel looked like a normal freighter without armor, fire control or high speed but with long range. The success of these auxiliary cruisers, in the manner the Germans deployed them, depended on deception, courage and surprise.

The Steiermark/Kormoran under construction on the Krupp Germaniawerft in Kiel Source: http://Bismarck-class

Before Kormoran started hunting in Australian waters, between January 13 and September 26, 1941, she had already sunk four Greek, one Yugoslavian, three British and an Australian merchantman and had captured a Canadian tanker. These 11 vessels totaled 6,275 ton of Allied shipping space. Hence, Kormoran was a very successful raider, as these vessels were called by the Allies.

Definitielijst

- battleship

- Heavily armoured warship with very heavy artillery.

- cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

- Kriegsmarine

- Germa navy. Part of the Wehrmacht next to Heer and Luftwaffe.

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

HMAS Sydney versus Kormoran

Korvettenkapitän Detmers had intended to lay mines off Fremantle when he concluded from intercepted Australian radio signals that two heavy cruisers, HMS Cornwall and HMS Dorsetshire had just left this port to escort a convoy. He discarded his previous plan but remained in the waters off Australia's west coast. In the late afternoon of November 19, 1941, some 170 miles off Shark Bay on the west coast of Australia he accidentally met HMAS Sydney.

HMAS Sydney commanded by Captain Joseph Burnett immediately asked for the identity of the spotted German raider by means of flag signals. Her commander knew evasion was no longer possible and Detmers ordered to hoist the Dutch flag to confuse the enemy ship and signaled Straat Malakka in response. This was a new vessel of the Koninklijke Paketvaart Maatschappij that might be sailing in these waters. The Germans started a cat-and-mouse game by lingering to send the correct information back to the Australian cruiser. Here the Sydney made the fatal mistake to steadily approach the German cruiser without launching her float plane which was standing by. At the very short distance of 3,000 yards, the light cruiser turned her broadside towards Kormoran, pointing her four 15cm twin turrets and the four port torpedo tubes threateningly at the other vessel.

At the end, the mutual distance had decreased to 1,000 yards. Now the Sydney signaled the letters 'i' and 'k' , the first and third characters of the secret call sign of the real Straat Malakka, which was unknown aboard the German raider. Commander Detmers, who obviously couldn't respond to this signal, was forced to drop his disguise. Time was now 17:30 and the German commander gave the order Fallen Tarnung! (drop disguise).

The following events unfolded very rapidly. Kormoran opened fire with her 15cm guns, scoring direct hits immediately. The next salvo from the Australian cruiser with her 15cm guns was aimed too high.

As both vessels were so close, the German vessel could deploy her lighter batteries as well. While Kormoran fired eight salvoes with her 15cm guns with a five second interval, her lighter batteries plastered the upper deck, the anti-aircraft guns, the torpedo batteries and the bridge of the light cruiser. Both forward turrets of the Sydney had obviously been put out of action quickly but the aft turrets scored a few direct hits on Kormoran, destroying her boiler room and the generators on the main engines and the fuel tanks were set on fire. Meanwhile, Kormoran had launched two torpedoes, one of them striking the unfortunate light cruiser beneath both forward turrets.

Subsequently, Sydney ceased fire and with her bow deep in the water, she closed in on the enemy vessel, probably in an attempt to ram her. At that moment the entire superstructure of her second gun turret was blown off after a new salvo by the German vessel. Sydney still managed to launch four torpedoes at the enemy but they all missed before she turned south and steamed slowly away, heavily on fire.

From Kormoran the burning ship could be traced in the falling darkness. The flames slowly died down and before midnight they had all gone out. Kormoran was heavily damaged itself as well and Detmers ordered 'abandon ship'. The survivors were taken aboard 11 life boats. A rubber raft with 50 men capsized in the growing swell and nearly all occupants drowned. Shortly after midnight the German commander was the last to leave his vessel after he had laid explosive charges which detonated shortly after. The ship remained afloat however until the fire reached the 360 mines and she went down after a gigantic explosion.

Definitielijst

- cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

Epilogue

The engagement between HMAS Sydney and Kormoran remains one of the weirdest events of the Second World War. The fact that an auxiliary cruiser, although very well armed but actually a normal merchantman, managed to destroy a modern cruiser in a one on one fight is unique. By getting too close to the enemy Sydney played completely into his hand, offering him the opportunity to deal the first, and in this case the heaviest blow. Furthermore the question remains unanswered why Australian commander Burnett didn't ask navy HQ in Australia whether the Dutch freighter Straat Malakka could indeed be in the area involved.

Three days later, when nothing was known yet about Sydney's fate, a similar encounter took place in the southern Atlantic between the British heavy cruiser HMS Devonshire and the German raider Atlantis. Here, the British demonstrated how to handle such a situation. On November 22, the catapult aircraft reported the presence of a suspect vessel. The Atlantis passed herself off as the Dutch freighter Polyphemus. Again, there were delays with the signals on the 'Dutch' vessel. Captain Oliver, commander of HMS Devonshire, deemed it possible the vessel could indeed be there and that she had problems with the British signals but he took no chances. Steaming at high speed, he kept a considerable distance and enquired by radio whether the vessel involved could indeed be in those waters. An hour later he got his answer: 'Negative, I repeat, negative'. The heavy cruiser immediately opened fire with her main 8" battery at a distance of over 13,000 yards, inflicting such damage on the Atlantis she had to be scuttled by her own crew.

Furthermore it is remarkable that all 645 crew members of the cruiser have perished. Not a single survivor has been picked up. This dramatic and extremely rare occurrence has attributed to the fact that the sinking of HMAS Sydney has left a deep impression on all Australians but in particular on the next of kin.

The survivors of Kormoran were kept imprisoned in Australia throughout the war. On January 27, 1947, they were repatriated by the ss Orontes. On leaving the port of Melbourne, the Straat Malakka was laying along the quay on the other side of the port.

On March 12, 2008, the 'Finding Sydney Foundation' announced that during a search mission costing AUD 3,9 million, donated by private and government funds and which had started early March, the wreck of the Kormoran had been found.

On March 16, it was announced that the wreck of HMAS Sydney had been found as well, 12 miles away from Kormoran at about 100 miles west of Steep Point, 260 southern latitude and 1110 eastern longitude at a depth of 8,100 feet. Next day, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd confirmed that the wreck had been positively identified as that of HMAS Sydney. On April 3, the first submarine pictures of Sydney and Kormoran, taken by an ROV, were published.

The wreck of HMAS Sydney will be protected pursuant to a law of 1976, the Historic Shipswreck Act and treated and honored as a war grave.

Definitielijst

- cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

Information

- Article by:

- Peter Kimenai

- Translated by:

- Arnold Palthe

- Published on:

- 18-12-2022

- Last edit on:

- 30-09-2024

- Feedback?

- Send it!