Introduction

Ilse Koch's name has been synonymous with the horrors of the concentration camps since the American tribunal at Dachau, which took place from November 1945 to August 1948. The blond wife of the camp commander was accused of the most heinous crimes and became notorious in Germany as "Die Hexe von Buchenwald." In the American media, she came to be known as "The Bitch of Buchenwald."

In Buchenwald

Ilse Koch was born Margarete Ilse Köhler in Dresden on September 2, 1906. After completing trade school she also worked as a stenographer at a cigarette company in Dresden. In April 1932, she joined the NSDAP. She married in 1936 at the age of 30 to Karl Otto Koch, 10 years older, with whom she would have three children, one of whom died shortly after birth. [1]

The couple moved to Buchenwald concentration camp where Karl had been appointed camp commander in 1937. Until his transfer to Majdanek in 1941, Karl Koch was guilty of large-scale corruption at Buchenwald. SS judge Konrad Morgen, who investigated this suspicion in 1943, discovered that Koch, together with several accomplices, had robbed, mistreated, and, without being ordered to do so, murdered prisoners. Ilse profited from the large amount of money her husband managed to embezzle. For example, a horse-riding hall worth a quarter of a million Reichmarks was built for her by prisoners.[2] SS judge Konrad noted in his investigative report of the Buchenwald case that "Frau Koch [...] has a character that was in no way inferior to her husbands in terms of greed, pride, and cruelty’.[3] He called her a nymphomaniac and accused her of having had sexual relations with her husband's colleagues.

In the camp she was notorious for her sadism; she would often beat prisoners with her whip while riding her horse. Morgen learned from witnesses that the commandant's wife often walked around the camp provocatively in " a short skirt and see-through blouse." She had male prisoners who dared to look at her, punished by the sadistic camp guard Martin Sommer. The victims were usually flogged twenty-five times; one prisoner reportedly died as a result of this beating. Morgen had Ilse Koch arrested on suspicion of complicity in her husband's crimes on August 25, 1943. She then spent 16 months on remand in the Weimar police prison until she was acquitted by the SS court. An SS court sentenced her husband to death. As late as April 5, 1945, with the Americans approaching the camp, Koch was executed at Buchenwald by an execution squad of the Schutzstaffel (SS).

Definitielijst

- Buchenwald

- Concentration camp established in 1937 near the city of Weimar.

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

Indicted by the Americans in Dachau

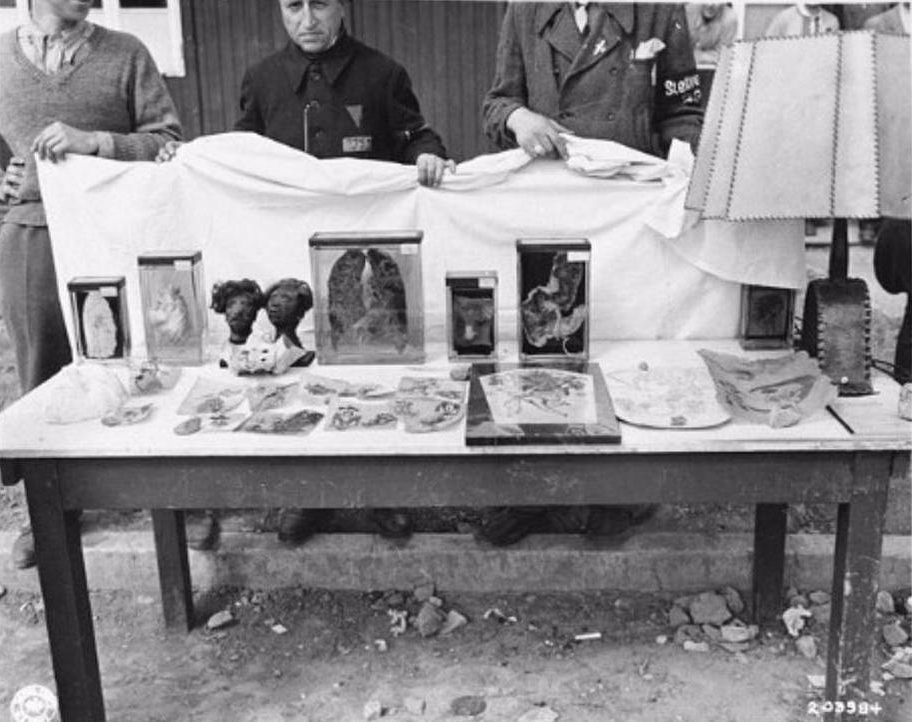

Ilse Koch was arrested by the U.S. Army in June 1945 at Ludwigsburg, where she was staying with relatives, and prosecuted at the former Dachau concentration camp for her crimes at Buchenwald. Most notoriously are charges that Ilse Koch allegedly made lampshades, gloves, book covers, and other utensils from the skin of prisoners she selected herself. After the liberation of the camp, the Americans displayed the material they had found, including preparations of human organs and tattooed human skin. Set up on the table was also a table lamp, believed to have been made from human skin. The accusation that Ilse Koch had this lamp made of human skin, spearheaded the prosecutor’s efforts during the U.S. Dachau tribunal, but tangible evidence was lacking, as the lampshade had since disappeared without a trace.[4]

The prosecution of Ilse Koch took an erratic course. On August 14, 1947, she was sentenced to life imprisonment at Dachau. She was spared the death penalty only because she had become pregnant (by a fellow inmate or prison employee) during her imprisonment. Ten witnesses had been subpoenaed including a Franciscan monk who had been imprisoned at Buchenwald. He testified that he had seen Ilse Koch one day write down the number of a prisoner with a distinctive tattoo of a sailing ship. The prisoner had been summoned that same evening by the camp guards before disappearing forever. Six months later, the monk is said to have seen a prepared piece of skin with the tattoo on it at the camp pathology department. Later he saw the tattoo again on the cover of a photo album of Ilse Koch.

However, the U.S. prosecutor was unable to present both this photo album and other utensils made from human skin because it was unknown where they had gone. Koch denied such objects had belonged to her and claimed that her role in the camp was overstated; she had only been a housewife and mother.

Definitielijst

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Dachau

- City in the German state of Bavaria where the Nazis established their first concentration camp.

Review of sentence and turmoil

Her life sentence was quietly converted to four years in prison on June 8, 1948. When that became known in the United States, it caused a stir. People remembered how she had been portrayed during the trial as the personification of evil. How could such a person be punished so lightly? Scathing editorials appeared in the media: "Perhaps our military revised the verdict only so Ilse Koch can get back into the lampshade business," the New York News reported. The New York Mirror called for them to "also open the prison cells in Atlanta, Leavenworth, and Alcatraz, where some soldiers are serving 20 years just because they hit an officer once." At a trade fair for German industry in New York, hundreds of people stood with protest signs saying, How expensive are Ilse Koch's lampshades? And when the German boxer Hein ten Hoff wanted to fight in America, the signs read, When is Ilse Koch coming to box?[5]

General Lucius D. Clay, the military governor of the American zone of occupation in Germany, who was responsible for reviewing Koch's sentence, defended himself by arguing that "the lessening of her sentence [was] consistent with the principles of American justice." According to him, the revision had not been an act of mercy or generosity, but rather the result of a study of the court records. This revealed that the accusations against Ilse Koch were not based on concrete evidence, but rather on hearsay.

The testimony of witnesses also turned out not to be sufficiently reliable. In reality, the witness mentioned above turned out not to be a Franciscan monk at all, but someone who had offered himself to the Americans for a hefty reward to testify against SS officers. His testimony was also contradictory; first, he claimed to have seen the sailboat tattoo on Ilse Koch's photo album, but later it was a lampshade on which he saw the tattoo. Two American correspondents, to whom the photo album had been shown, also stated that in their opinion it was not made of human skin and no tattoo could be seen on it.[6]

Preserved human skins

Conclusive evidence that in Buchenwald human skin had been preserved does exist by the way. An American pathologist examined three pieces of tattooed skin found in the camp shortly after its liberation and determined that they were of human origin. According to Morgen, these tattooed skins were removed from the corpses of deceased Gypsies and criminals for criminological research. The existence of a lampshade made of human skin has never been conclusively proven. Ilse Koch's involvement in the preparation of human skins has also never been proven.[7]

Displayed on a table in liberated Buchenwald, are tattooed pieces of human skin, human body parts in spirits and a lampshade that was supposed to have been made of human skin Source: NARA

’The power of propaganda and mass suggestion has never been better illustrated than in the case against Ilse Koch,’ was the stark conclusion formulated in the sentencing report on which Clay based his argument:

’Long before the trial, she had already been found guilty in the public mind as "the witch of Buchenwald." [...] Stories about her went from mouth to mouth and were embellished with ever more colorful details. But when it came to evidence in court, the bottom line was that the record lacked evidence for these stories.’[8]

Definitielijst

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

Released and prosecuted again

An investigation by a Senate committee nevertheless determined on December 27, 1948, that Koch had been involved in the killing and mistreatment of hundreds of prisoners: "The guilt of this bestial woman in specific murders is indisputably established."[9] Nevertheless, Ilse Koch was released from American custody on October 17, 1949, after which she was nonetheless taken back into pre-trial detention by the German judiciary. Because of the enormous commotion and the inability of the United States to re-prosecute her after she had served her sentence, General Clay insisted that the Germans take her to a German court. It was, including the prosecution during the war, the third time she had been on trial for her crimes at Buchenwald.[10] She was charged with murder and sentenced to life imprisonment for the second time on January 15, 1951. She still considered herself innocent. Psychiatrists determined during her prison sentence that she was "a perverted, nymphomaniacal, hysterical, and power-hungry demon."

Suicide

She committed suicide in a Bavarian prison on September 1, 1967, at the age of 61. "I cannot do otherwise. Death is the only redemption," she wrote to her son who was born in 1947 during her imprisonment (the father was a fellow inmate).[11]

Notes

- Stackelberg, R., The Routledge Companion to Nazi Germany, p. 311; Smith, A.L., Die Hexe von Buchenwald, p. 33

- Wistrich, R.S., Who’s who in Nazi Germany, p. 143.

- Morgen, K., Wesentliches Ermittlungsergebnis. Der Korruptionskomplex A. SS-Standartenfuehrer Koch, Harvard Law School Library, p. 50.

- "Ilse Koch Lady mit Lampenschirm", Der Spiegel, nr. 7, 16.02.1950.

- "Ilse Koch Lady mit Lampenschirm", Der Spiegel, nr. 7, 16.02.1950.

- "Ilse Koch Lady mit Lampenschirm", Der Spiegel, nr. 7, 16.02.1950.

- Stein, H., "Stimmt es, dass die SS im KZ Buchenwald Lampenschirme aus Menschenhaut anfertigen ließ?", op: www.buchenwald.de ; Recorded interview with John Toland, 25-10-1971, Franklin D. Roosevelt Library.

- "Ilse Koch Lady mit Lampenschirm", Der Spiegel, nr. 7, 16.02.1950.

- Snyder, L.L., Encyclopedia of the Third Reich, p. 198.

- "Ilse Koch Lady mit Lampenschirm", Der Spiegel, nr. 7, 16.02.1950.

- Snyder, L.L., Encyclopedia of the Third Reich, p. 198.

Information

- Article by:

- Kevin Prenger

- Translated by:

- Fernando Lynch

- Published on:

- 19-01-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!