Introduction

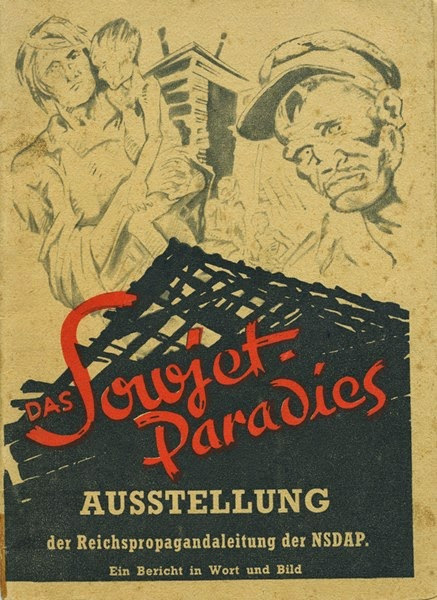

On May 18, 1942, an anti-Nazi and a Communist group set fire to the anti-Soviet exhibition, Das Sowjetparadies (Soviet paradise), which was held in the Lustgarten in Berlin. However, Victor Klemperer would not write about the event before June 8. The German-Jewish author was a passionate chronicler in his time (1881-1960), who gained fame posthumously because of his diaries. He accurately documented his Ausgrenzung (exclusion), describing his experience of being excluded from German society. The German press had kept the incident secret, but Klemperer learned about it orally.

Herbert Baum, (June 11, 1942 - February 10, 1912). Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-32713-0001 / CC-BY-SA 3.0

About the 'Jewish arson', he wrote:

'500 people have been arrested. Of them, 30 have been released, 220 have been deported to concentration camps, 250 have been shot en the families of all 470 people in custody were 'evacuated''. Five days later, the minister of public information and propaganda Joseph Goebbels wrote in his diary:

'We have unmasked a group of saboteurs and murderers in Berlin. Among them are the groups which were involved with the bombing attack on the Das Sowjetparadies exhibition. It is noteworthy that among those detained were five Jews, three half-Jews and four Aryans. Even an engineer of Siemens was involved. The bombs were partially made in the Kaiser-Wilhelm Institut.'

Herbert and Marianne Cohn-Baum before they married in 1926 or 1927. They are encircled in white and Olga Benario is encircled in grey. Source: Wikimedia

For Goebbels, this incident was the direct cause to urge Adolf Hitler to deport all Jewish people from Berlin. At the time of the incident, 40.000 Jews still lived in town. The culprits of the arson were members of the Herbert-Baum-Gruppe.

Definitielijst

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

The Herbert-Baum-Gruppe

This group was named after its leader Herbert Baum. Herbert was born on February 10, 1912 in Poznan, the son of an accountant. He grew up in Berlin and became an electrician. From 1926 on, he joined several Jewish youth organizations and in 1931, he became a member of the Communist youth federation. After 1933, he was a part of the resistance of the KPD (German communist party). Soon young Communist men and women of Jewish descent started to form a group around Herbert, forming the early Baum-Gruppe. Herbert Baum organized meetings, often located in the outskirts of Berlin, with his wife Marianne and the befriended couple Martin and Sala Kochmann. During these meetings, the threat of Nazis in power was discussed, but cultural topics and Marxist literature were naturally also commonly discussed. Baum, however, also contacted other non-Jewish resistance groups, including the group of Werner Steinbrink. Non-Jewish people had more freedom than Jewish people, which was needed for several activities of the Baum-Gruppe. The contact with Steinbrink would prove to be important for the attack on the Soviet exposition since Steinbrink worked at the Kaiser-Wilhelm Institute: the place where the bombs were partially made.

Meanwhile, in 1935, Baum took evening classes to become an electro-engineer. He was soon banned from this training because he was Jewish. From 1941 onwards, Baum had to work at the ‘Jew department’ of the Siemens factory in Berlin. He met other forced laborers at this department. He helped hiding a few of them to prevent them from being deportated to the extermination camps, while others joined Baum’s resistance.

Definitielijst

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

The attack

From early 1942 on, the Baum-Gruppe mainly wrote and distributed pamphlets against the war. The main targets were doctors and soldiers, but also housewives were addressed. Baum and Steinbrink both felt pressured to overthrow the Nazi regime, and they thought that the German people were ready for a revolution. An important cause for this thought was the fact that the military advance into Russia was not going as well as expected. Moreover, both men thought the world needed to know that within Germany there was resistance against the Nazi regime as well. Baum and Steinbrink therefore sought an object to show their resistance and they came across the Soviet exhibition, which would take place on May 18, 1942. The plan to hold such an anti-Soviet exposition was proposed by Goebbels. His aim was to increase the people’s enthusiasm for the war by showcasing the pitiful working conditions of Russian so-called workers' paradises.

The exhibition had already been held in Vienna, Prague and Paris, after which Berlin was planned. The exposition consisted of several large tents, which were set up in Lustgarten; a former garden of the Berlin Stadtschloss (city palace). A section of the tent was tiled for manifestations by the Nazis. The decision to bomb the Lustgarten was not made unanimously though. Several members had indicated they were afraid of repercussions but preparations continued nonetheless. According to the original plan, the bombing was supposed to take place on Sunday May 17, but the risk that a large crowd would turn up at the event postponed the attack to the next day. The perpetrators ran a lower risk of getting caught with a large crowd and they also did not want to injure innocent bystanders. The next day, their wish for fewer people was fulfilled because it had started to rain. During previous inspections, a model of a Russian restaurant seemed suitable, but that day the tent was closed. The replication of a house of a Russian craftsman was chosen instead. The explosives were planted (according to Goebbels, there were five bombs) and the men fled from the scene. The result they had hoped for was disappointing. The resulting fires were extinguished quickly, there were no deaths and only eleven people had trouble breathing because of the smoke. Another setback was that the exposition opened the next day as usual.

Definitielijst

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- revolution

- Usually sudden and violent reversal of existing (political) the political set-up and situations.

Consequences

Despite the minimal effect of the attack, repercussions quickly arose in three forms: reprisals, arrests, and trials. Reprisals consisted of arresting 500 Berlin Jews and group members. Half of them were shot immediately while the others were sent to Sachsenhausen, where they died several months later.

The arrests and trials took place in three phases: the first wave of arrests of group members took place four days after the attack and lasted until summer. Rumors spoke of the involvement of a traitor, a spy of the Gestapo, and it was thought for a long time that Joachim Franke was the traitor. Together with Steinbrink, Franke was the leader of the Steinbrink-Franke group. Franke’s motive would have been to save his wife’s life. However, Franke’s involvement has been doubted because he did not know most of the group members.

The second wave started on March 4, 1943. The Nazis held short trials for both the arrested Jews from Berlin as well as members of resistance groups. Most detainees were sentenced to the guillotine. A few of them were sentenced to prison terms but were eventually sent to concentration camps. The third and final group was taken to court on September 7, 1943. This group consisted of only three members, who were arrested after the previous trails. They were not executed by the guillotine like the other detainees because the device in Plötzensee-prison had been damaged during an air-raid. They were hanged instead.

Herbert Baum died on June 11, 1942, in Moabit prison. The circumstances of his death are still dubious. It was possibly a suicide, but torture could also have been the cause of death. He was buried at the Jewish cemetery at Weissensee. Steinbrink was killed on August 18, 1942, in Plötzensee-Berlin.

Definitielijst

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Epilogue

Was the attack worth the sacrifice? In any case, the goals were not achieved. The German people only learned of the failed attack during the Russian campaign after the Battle of Stalingrad in January 1943. The hope that the world would note the resistance in Germany was also not fulfilled. The group had missed the fact that the Nazis fully controlled the media. They would see to it that no discord would find its way to the outside world. The news could only be transferred orally, which happened at snail's pace. The question is whether Baum and his group knew they were risking the lives of many innocent people who were arrested as part of the reprisals. If that had been the case, the decision to take the risk would have been much easier since the death of Jewish people was inevitable. Nevertheless, Baum had done his research before acting. He had sent five people, who hardly looked like Jews, to the exposition site but he had also fashioned a grand plan to escape to France. During his work at Siemens, Baum had contacted non-Jewish forced laborers from France, after which he received false identification documents for a few members of his group. His plan, however, failed and the consequences are known.

It goes without saying that attempts at overthrowing the regime carry ethical problems, which makes it difficult to distinguish right from wrong. After more than 70 years, it seems much easier to determine the rights and wrongs of people in oppression. The action of the Baum-Gruppe in itself was not very impressive, but the fact that it was organized by a large group of Jews (with Communist motives) makes it special. In all honesty, however, it was not as heroic as it might seem. The Baum-Gruppe was also known for other, more dismal activities. The group needed money to fund their anti-Nazi activities. They asked for contributions in the form of household goods from Jews who were getting ready to be taken to camps, which were then sold to fund the resistance. However, many people declined the offer, because many were unaware of what was happening at these camps and expected to return at some point. Baum, Steinbrinck, and Birnbaum, who was a member of the group but not Jewish, took possession of the goods, pretending to be Gestapo-officers sent to claim certain goods, including a portable typewriter, a painting, and a few eastern tapestries. Their actions did yield a fair amount of money.

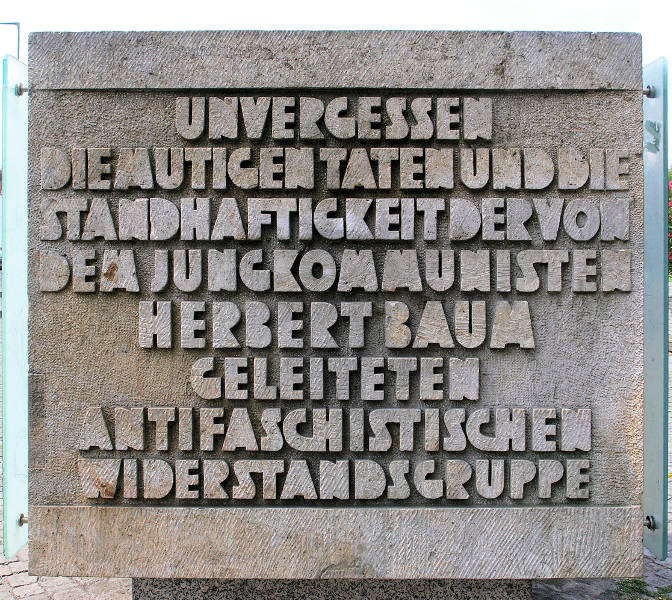

Herbert Baum was a very charismatic and convincing person. Both Herbert and his wife were a bit romantic, which led to outsiders accusing them of being indifferent. On the other hand, Baum called for extreme loyalty from the members in his group, even with the people who were against the attack. The archive describing the Baum-Gruppe remained classified for many years. Only things matching DDR, Deutsche Demokratische Republik, or Eastern Germany) policy was made public, in particular the activities of Comminist resistance groups. A memorial was commissioned by the magistrate of East-Berlin and made by sculptor Jürgen Raue in 1981 to remember their heroic acts of resistance in 1942. The monument was erected in the Lustgarten, at the site of the attack.

Memorial stone of Herbert Baum, at the Lustgarten in Berlin. The text reads: To not forget the brave deeds and the endurance of the young Communistic, anti-Fascist resistance group led by Herbert Baum. Source: Wikimedia

Definitielijst

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Information

- Article by:

- Annabel Junge

- Translated by:

- Thomas van der Veld

- Published on:

- 22-04-2023

- Last edit on:

- 27-04-2023

- Feedback?

- Send it!