Introduction

Mighty Hood, that is how the British called the battlecruiser HMS Hood in the period between both world wars. During that period, she was indeed the largest battleship in the world and the British were proud of their symbol of maritime military power. The vessel strongly appealed to the imagination by her fire power, speed and dimensions in a period in which the British population and that of the colonies felt a strong affinity towards the Royal Navy

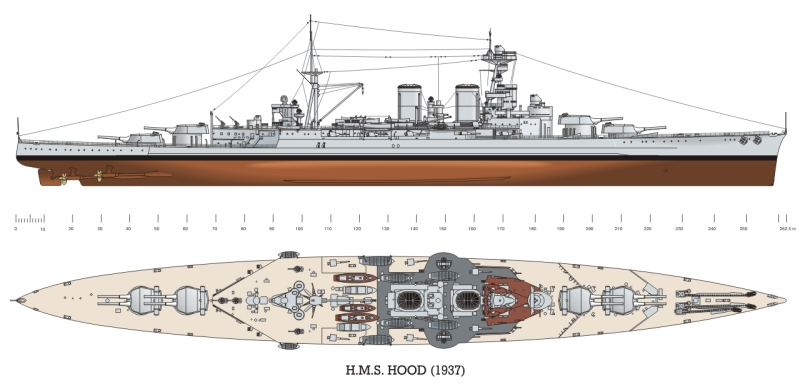

HMS Hood was one of the four Admiral class battlecruisers which were ordered in 1916 in response to the fast, 28 knots German Mackensen class battlecruisers. Her design was adapted after the loss of HMS Queen Mary, Indefatigable and HMS Invincible during the Battle of Jutland on May 31 and June 1, 1916 As the three battlecruisers had been lost because of cordite explosions, 5,000 tons of additional armor was added to the design. Nonetheless, the 3 inch deck armor remained the Achilles heel of the design. The vulnerable magazines were still insufficiently protected against shells striking at high angle.

Construction of HMS Hood began on September 1, 1916 on the shipyard of John Brown & Company Ltd. in Clydebank, Scotland. Construction of her three sisterships, Howe, Rodney and Anson was postponed in 1917 when it became clear that her German opponents of the Mackensen class wouldn't be completed. Moreover, the design problems of the Admiral class were recognized when it turned out that due to the additional armor, the Hood was too low in the water, making the internal tension of the hull too strong. It was seriously considered to dismantle the Hood even before her launch but the bad financial situation at the end of the First World War made the British Admiralty decide to continue construction nonetheless instead of starting all over again. It was decided however to cancel the construction of the three other battlecruisers.

On august 22, 1918, HMS Hood was launched. After completion and trial runs, she was commissioned on May 1, 1920 by Captain Wilfred Tomkinson. She was immediately named flagship of the Atlantic Battlecruiser Squadron commanded by Rear Admiral Sir Roger Keyes.

Due to so much additional armor, she really was no battlecruiser anymore. Those were in fact vessels with the firepower of a battleship but with a higher speed as less armor was fitted, reducing the overall weight. But despite her total displacement of 41,125 BRT, she could reach a speed of 31 knots. She did have the speed of a cruiser though but not the maneuverability. therefore she actually was a fast battleship. The British persisted however, she was a battlecruiser.

Over the years, 20 different launching devices for Fairey Flycatchers or Fairey IIIF aircraft were fitted on top of two 15inch guns and on the aft deck. As the was actually too deep in the water, there was always heavy spray at sea, often causing damage to the aircraft. Moreover, much damage was caused to the launch installations like catapults and cranes and the aircraft themselves by the recoil of the main guns. In 1933, the last devices for launch and recovery of aircraft were removed definitely.

Definitielijst

- battleship

- Heavily armoured warship with very heavy artillery.

- cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

- Squadron

- A military unit in the Belgian navy usually six to eight small ships operating together under one command. The smallest military unit in the Dutch air force of about 350 men. In most countries is the designation of a military unit thesize of a company. It is either an independent unit, such as a battery, or part of a bigger Calvary unit. In the air force it is the designation of a unit of aircrafts.

Technical data

| Built by | John Brown & Company |

| Ordered | April 7, 1916 |

| Laid down | September 1, 1916 |

| Launched | August 22, 1918 |

| Commissioned | May 15, 1920 |

| Class | Admiral class |

| Type | Battlecruiser |

| Displacement standard 1920 | 41,125 BRT |

| Displ. fully loaded | 46,680 BRT |

| Displ. standard 1931 | 40,037 BRT |

| Displ. fully loaded | 48,000 BRT |

| Displ. standard 1939 | 42,462 BRT |

| Displ. fully loaded | 48,360 BRT |

| Length overall | 861 feet |

| Beam | 105 feet |

| Draught | 33 feet |

| Armor belt | 4 to 12 inch |

| Armor deck | 0.7 to 3 inch |

| Armor turrets | 11 to 15 inch |

| Powerplant boilers | 24 Yarrow small tube, 3 drums |

| Steam turbines | 4 Brown-Curtis single reduction, 1 per axle. 1 Brown-Curtis Cruise |

| Power output | 151,200 hp |

| Propellors | 4 three-bladed, 15 feet diameter |

| Fuel capacity | 4,000 tons of fuel oil |

| Top speed | 31 knots (29 in 1939) |

| Crew, peacetime | 1,169 heads |

| Crew wartime | 1,418 heads |

| Main armament | 8 Mk I 15inch in 4 turrets |

| Secondary armament 1920 | 12 Mk I 5.5inch |

| Sec. armament 1939 | 14 twin Mk XVI 4inch AA guns |

| AA guns in 1920 | 8 single Mk V 4inch |

| AA 1939 | 24 triple Mk VIII 40mm pom-pom, 5 quadruple Mk III Vickers 12.7mm, 5 20 barrel rocket launchers |

| Torpedo tubes 1920 | 2 Mk IV 53.34cm below waterline |

| Tubes | 4 Mk V 53.34 above |

| Torpedo tubes 1939 | 4 Mk V 53.34cm above waterline |

Definitielijst

- rocket

- A projectile propelled by a rearward facing series of explosions.

- Torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

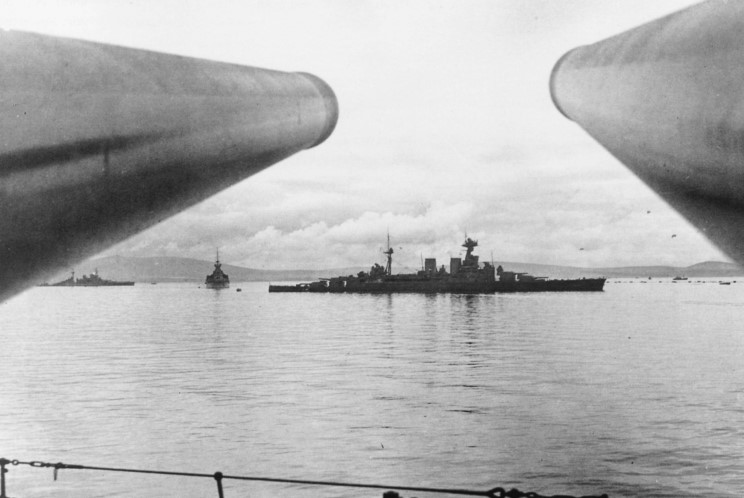

HMS Hood before WW II

From her commission onwards, HMS Hood was mostly used for flag display. To his end, the battlecruiser became the flagship of the Special Service Squadron, commanded by vice-Admiral Sir Frederick Field which further included the battlecruiser HMS Repulse (34) and the light cruisers HMS Delhi, Danae, Dauntless, Dragon and HMS Dunedin. In particular during the so-called Empire Cruise form November, 27 1923 to September 28, 1924, HMS Hood gained world fame. During this voyage, over 38,000 nautical miles were covered and visits were paid to many British colonies and all countries of the British Commonwealth. The United States of America were visited as well. During this world cruise, over a million people visited the vessels of the Special Service Squadron and almost 750,000 visited HMS Hood.

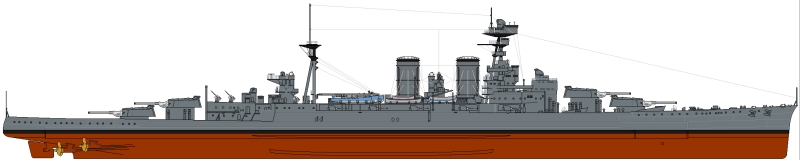

From May 1, 1929 to June 16, 1931, the vessel was upgraded in Portsmouth in southern England. During this period the bridge was renovated and adaptations were made to the fire control of the secondary armament. After this modernizing, the vessel was put back in service and Captain J.F.C. Patterson took command. HMS Hood was made flagship of the Atlantic Battle Cruiser Squadron again and her former commander, vice-Admiral Tomkinson was made flag officer of this flotilla.

In mid-September 1931, her crew was involved in the Invergordon Mutiny. This wasn't a real mutiny but more of a series of strikes and interruptions of work aboard most British capital ships. They had assembled in Invergordon, Scotland for a massive fleet exercise. British Admiralty had announced to lower the wages of the Royal Navy personnel in connection to the global economic recession. Promises were made to limit the reduction of wages when it turned out that the Invergordon Mutiny created panic on the London Stock Exchange causing the British economy to deteriorate even further.

HMS Hood in 1930. Clearly visible: she is too deep in the water. Source: Courtesy of Michael W. Pocock

Halfway through the 30s, many cruises in the Atlantic and Mediterranean followed. These flag waving and training trips with HMS Hood as the flagship of the Cruiser Squadron, were only interrupted by short periods of maintenance. On July 22, 1936, the vessel was assigned to the Mediterranean Fleet operating from Gibraltar and Malta.

During the Spanish Civil War, which lasted from July 1936 to April 1939, Great Britain remained neutral but British vessels were regularly threatened by the Nationalistic navy vessels under General Francisco Franco, supported by Italian and German warships. In order to protect British and other neutral vessels, the Combined Fleet was established and based in Gibraltar.

HMS Hood was part of this flotilla and has actually targeted her guns at two Spanish Nationalistic cruisers, the Almirante Cervera and Galerna. These vessels wanted to stop three merchantmen on April 23, 1937 on their way from France to Bilbao to deliver supplies to General Franco's enemies. The Nationalistic cruisers retreated and supply to Bilbao could be completed.

The maintenance during the first half of 1939 was limited to the absolute necessities such as reparation of the turbines and on the outside of the hull below the waterline of the battlecruiser. Improvements were made however to the belt armor. Meanwhile, tension between Great Britain and Germany mounted and construction of the new King George V class battleships was given priority. The poor condition HMS Hood was still in, even after maintenance meant among other things she could only reach a top speed of 29 knots.

Actually, a major overhaul was planned for 1939. The command tower, weighing 600 tons and situated between the upper 38.1cm turret and the bridge complex, was to be removed entirely, but in particular her deck armor was to be improved. The outbreak of World War Two on September 3, 1939 caused the plans to be postponed. Not a single capital ship could be missed in the first stage of the battle. The five battleships of the King George V class hadn't been completed yet and the only fast battlecruisers, apart from HMS Hood were HMS Renown (72), Repulse (34), Rodney and HMS Nelson.

Definitielijst

- Commonwealth

- Intergovernmental organisation of independent states in the former British Empire. A bomber crew could include an English pilot, a Welsh navigator, air gunners from Australia or New Zealand. There were also non-commonwealth Poles and Czechs in Bomber Command.

- Cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

- mid

- Military intelligence service.

- Mutiny

- Revolt of soldiers or sailors against the authorities.

- Spanish Civil War

- Fierce and cruel civil armed conflict in Spain from 1936 to 1939 between left (from anarchic to liberal) and right (church, nobility and army). In 1936 the fascist-oriented general Franco started military uprisings. With the help of Hitler and Mussolini he beat the republicans who vainly were supported by the International Brigade.

- Squadron

- A military unit in the Belgian navy usually six to eight small ships operating together under one command. The smallest military unit in the Dutch air force of about 350 men. In most countries is the designation of a military unit thesize of a company. It is either an independent unit, such as a battery, or part of a bigger Calvary unit. In the air force it is the designation of a unit of aircrafts.

HMS Hood in the first stage of the war

At the outbreak of the war at sea, HMS Hood was the flagship of the Atlantic Battle Cruiser Squadron. This flotilla was part of the Home Fleet which operated from Scapa Flow in Scotland. From here, the vessels patrolled the north Atlantic. The main task of the Home Fleet entailed protecting merchantmen and hunting down German warships trying to break through to this part of the ocean.

On September 26, 1939, she was struck by a 500lbs bomb from a German Junkers Ju 88 bomber. The bomb hit the vessel on the port side but ricocheted off and exploded in the water. Damage was minor and she could be repaired in Scapa Flow.

From December 1939 onwards, the first Allied convoys of merchantmen were assembled so they could be better protected against attacks by German U-boats and surface vessels. From this date on, the main task of the Home Fleet was escorting these convoys. Very important in this connection were the first troop transports from Canada and the convoys carrying iron ore from Norway.

In this stage of the war, the British vessels were often supported by their French allies. This ended when France capitulated on June 25, 1940. HMS Hood was assigned to Force H. This fleet, commanded by vice-Admiral Sir James Sommerville, further included the carrier HMS Royal, the battlecruisers HMS Valiant and Resolution, the cruisers HMS Arethusa, Enterprise and 11 destroyers. Force H was to take on the defense of the western Mediterranean to fill the gap that was created by the disappearance of the French units

These units posed a threat to Great Britain. Winston Churchill was afraid the French vessels would be added to the German battle fleet, despite promises by the French secretary of the French Navy, Amiral Darlan that this had been clearly prohibited in the negotiations for the capitulation. The British didn't take chances however and launched Operation Catapult. This entailed bringing French warships under British control. The French vessels were dispersed over a large number of ports including the British-Egyptian Alexandria and Plymouth and Portsmouth in southern England. These vessels were quickly overpowered which evoked great outrage amongst the French.

The major part of the French fleet however was at anchor in the French-Algerian port of Mers-el-Kebir. This fleet, commanded by Amiral Gensoul, was offered an ultimatum by the commander of H Force, vice-Admiral Sommerville on behalf of Winston Churchill. This ultimatum entailed nothing more or less than that the French vessels were to head to a British controlled port or be destroyed on site. The message bogged down in disrupted communication and incorrect assumptions and on July 3, 1940 at 16:56, HMS Hood opened fire on her former allies. The battleships HMS Valiant and Resolution also opened fire with their 38.1cm guns on the French vessels at anchor. Fairey Swordfish aircraft from HMS Ark Royal had blocked the entrance to the harbor with magnetic mines and also dropped bombs and torpedoes.

The French vessels returned the British fire but had no free field of fire and couldn't deploy all their guns because they had no room to maneuver. Hence they didn't stand a chance against the British attack. The French battleship Bretagne was struck by nine 38.1cm shells within 11 minutes and exploded, claiming the lives of 1,012 crew members. The battleships Provence and Dunkerque suffered severe damage. At 17:05, the French vessels ceased fire and the Battle of Mers-el-Kebir was over. Over 1.300 French were killed and over 350 injured. Despite the blockade of the harbor, the battleship Strasbourg escaped to the French harbor of Toulon along with four destroyers.

The world had been shocked by the Battle of Mers-el-Kebir. The Germans used the battle in their anti-British propaganda. The British however showed, they were willing to go all out to defeat Germany. Vice-Admiral Sommerville was less pleased however and described his bitter feelings about the battle as: 'The biggest political blunder of modern times and will rouse the world against us …… we all feel thoroughly ashamed'. After Operation Catapult, the relationship between France and Great Britain had deteriorated strongly and it would take years to improve even a little.

In August, HMS Hood returned to Scapa Flow in order to reinforce the Home Fleet. The Battle of Britain was at its peak and HMS Hood, Nelson and Rodney were dispatched to Rosyth near Edinburgh, Scotland to be in a better position to face an eventual German invasion fleet. After the acute danger of an invasion had died down, the battlecruiser was reassigned to the Battlecruiser Squadron and resumed her patrols in the north Atlantic. Between January 13 to March 18, 1941, she underwent a major overhaul in Rosyth. There was no more time nor means to carry out more than overdue maintenance. HMS Hoodremained in a poor condition when she was redeployed against the German surface raiders.

Definitielijst

- battleship

- Heavily armoured warship with very heavy artillery.

- capitulation

- Agreement between fighting parties concerning the surrender of a country or an army.

- Cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- Squadron

- A military unit in the Belgian navy usually six to eight small ships operating together under one command. The smallest military unit in the Dutch air force of about 350 men. In most countries is the designation of a military unit thesize of a company. It is either an independent unit, such as a battery, or part of a bigger Calvary unit. In the air force it is the designation of a unit of aircrafts.

- surface raiders

- Heavily armed and fast merchant vessels, mostly used by the Germans in the early years of both World Wars.

Demise of HMS Hood

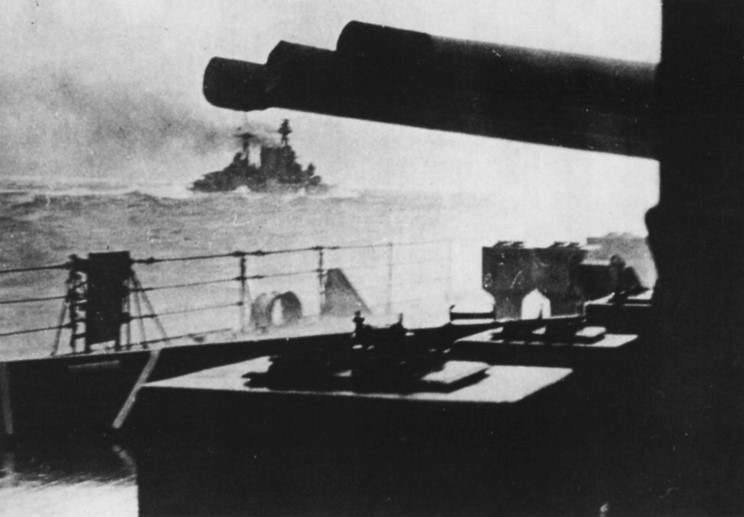

In May 1941, the new German battleship Bismarck and the equally new heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen set sail from the Grimdstadfjord in Norway to launch Operation Rheinübung. This meant that both surface raiders were to break through to the Atlantic to attack and destroy Allied convoys. Commander-in-Chief of the Home Fleet, Admiraal Tovey had no idea what course the German vessels would take and therefore he had to split his available forces in various battle flotillas. HMS Hood, along with the brand new battleship HMS Prince of Wales (53) and six destroyers under overall command of vice-Admiral L.E. Holland, was sent to Iceland to look for Bismarck and Prinz Eugen.

In the evening of May 23, both German vessels were picked up by radar aboard the heavy cruiser HMS Suffolk, patrolling in the Strait of Denmark between Iceland and Greenland with her sistership HMS Norfolk. The battle flotilla closest to the German vessels was that of vice-Admiral Holland with HMS Hood and Prince of Wales as its nucleus. Out of all Tovey's vessels, these two were the least suitable to take on the Bismarck. HMS Hood, well known as it was, had poor deck armor and the crew of HMS Prince of Wales could be hardly called battle ready. There even were some civilians of the shipyard still aboard to see to the last details before delivery.

Vice-Admiral Holland was left with no other choice than to attack the German vessels. He couldn't wait until all British battleships had joined him because in the meantime, Bismarck and Prinz Eugen could have broken through to the open Atlantic. He steamed north at high speed in the direction of the German warships which were still pursued by HMS Suffolk and Norfolk. During the night, contact with the German vessels was lost for a short time due to heavy snow storms. Holland dispatched his destroyers to find the German vessels. Once the two British ships had restored contact, HMS Hood and Prince of Wales were a bit too far to the north.

Holland altered course so his vessels were on parallel course with the German vessels with Prinz Eugen in the lead. The British commander wanted to decrease the distance to the German vessels as soon as possible in order to protect the vulnerable deck armor of HMS Hood as long as possible against the German shells which could come in from afar under a high angle. Therefore, Holland had his vessels swing 20 degrees to starboard. Because he was heading for the German vessels though, the Hood and Prince of Wales could only deploy their forward turrets whereas the Germans could deploy all guns against the British vessels. An additional disadvantage for the British was they couldn't use their destroyers for cover as they were still too far away, having searched in vain for the two German vessels.

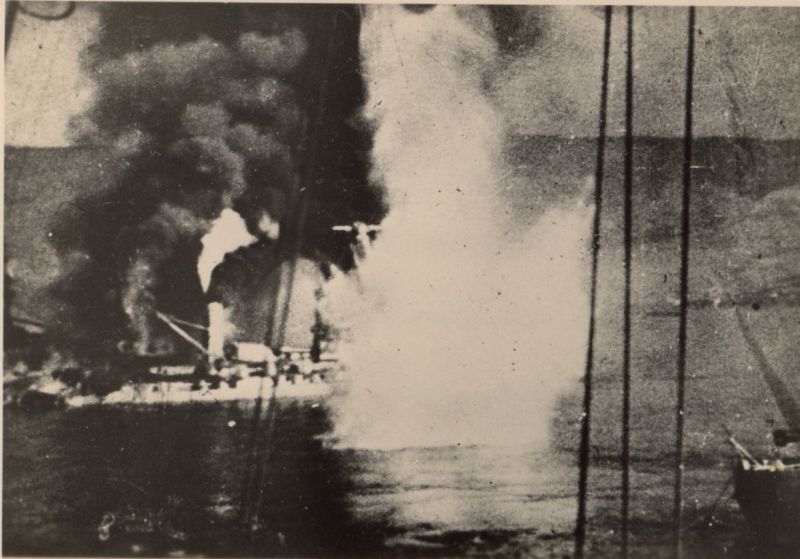

On 05:49, HMS Hood opened fire on the leading ship, assumed to be the Bismarck from a distance of 14.2 miles. As the British vessels steadily approached the German ships at high speed, Holland recognized the leading vessel as the Prinz Eugen and had his fire switched to the rear ship. Valuable time had been lost and the artillery officer of the Hood had to fire a new round and based on the observations from the fire direction control correct it. Both vessels opened fire on HMS Hood which was struck by a 20.3cm shell from the German cruiser, causing fire to erupt near the 10.2cm magazine. A little later, 38cm shells from the Bismarck came down in the water close to HMS Hood. She started a 20 degree turn to port to come on a parallel course to the German vessels in other to deploy her aft turrets as well.

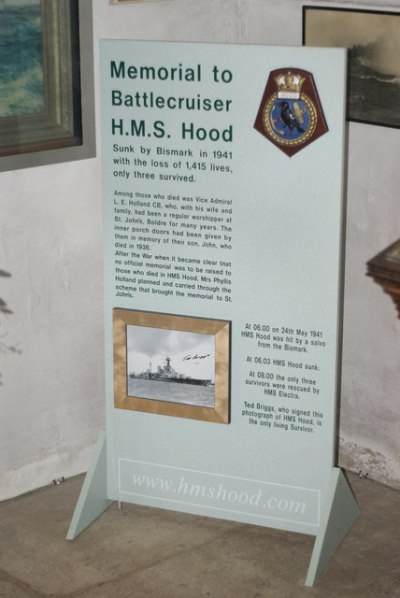

At 06:00, while still turning, shells from Bismarck's fifth salvo penetrated her decks and exploded inside a magazine. Almost immediately, an immense stab flame shot up near the main mast followed by a destructive explosion, causing the battlecruiser to break in half. The smallest, aft section of the vessel sank very fast and the larger bow section rose out of the water before disappearing in the ice cold water of the Denmark Strait. The pride of the Royal Navy had been utterly destroyed within three minutes. Only 11 minutes had passed after her first salvo and her doom. Out of the 1,418 crew members, only 3 survived who were picked up from the cold water 2.5 hours later by the destroyer HMS Electra. Vice-Admiral Holland and her commander Captain Kerr, went down with their ship.

HMS Prince of Wales had managed to score a number of hits on the Bismarck but was hit four times herself by the German battleship and three times by the other vessel. She broke off the fight and joined the heavy cruisers HMS Suffolk and Norfolk later which were still tailing the German battleships. Her hits on Bismarck had caused minor but important damage. There was a leak in one of the forward oil tanks causing the vessel to lose valuable fuel. Moreover, her maximum speed had dropped to 28 knots because one of the engine rooms had been flooded.

The dramatic loss of HMS Hood caused a great shock amongst the British. Everything in the book was pulled out to attempt and sink the Bismarck which eventually succeeded on May 27, 1941.

Definitielijst

- battleship

- Heavily armoured warship with very heavy artillery.

- cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

- destroyer

- Very light, fast and agile warship, intended to destroy large enemy ships by surprise attack and eliminating them by using torpedoes.

- radar

- English abbreviation meaning: Radio Detection And Ranging. System to detect the presence, distance, speed and direction of an object, such as ships and airplanes, using electromagnetic waves.

- surface raiders

- Heavily armed and fast merchant vessels, mostly used by the Germans in the early years of both World Wars.

Epilogue

As early as June 2, 1941, an investigation committee headed by vice-Admiral Geoffrey Blake reached the conclusion that HMS Hood had gone down as a result of a direct penetration by one or more 38.1cm shells, fired from a distance of 9.3 miles through the deck armor. This triggered the explosion of one or more of the aft magazines.

The results of the investigation by this committee met fierce criticism as no witnesses had been heard. Moreover, various influential persons came up with different theories as to the sinking of the vessel. One of them, which originated from Sir Stanley Goodall, Director of Naval Construction, was about an explosion of her own torpedoes. Another assumed a hit by a shell below the belt armor and a third theory named the 20.3cm shell of Prinz Eugen as the cause of a fatal fire.

A second investigation committee was called, chaired by vice-Admiral Sir Harold Walker. This committee dug deeper than the previous one and heard for instance 176 eyewitnesses including the commander of HMS Prince of Wales (53), Captain Leach. All suggested theories were investigated as well but the eventual result differed little from the previous one. In September, the official verdict was announced: 'The sinking of HMS Hood was caused by the hit of a 38.1cm shell from Bismarck in or near the vessel's aft 10.2 or 38.1cm magazine, resulting in the explosion of these magazines that caused the destruction of the aft part of the vessel. It is likely that the aft 10.2cm magazine was the first to explode'.

Nearly the same conclusions by the committees exonerated vice-Admiral Holland of all negative charges or possible incorrect actions. The fast sinking of HMS Hood was entirely due to the bad deck armor. Her design had simply not been good enough. After a long period in which she was considered the finest battleship in the world, she was sunk in three minutes on her first real confrontation with the enemy. Mighty Hood proved to be powerless in a direct confrontation with a comparable opponent.

In November 1965, survivor William Dundas died in a car crash near Stirling, Scotland. Almost 30 years on, in February 1955, survivor Bob Tilburn died of natural causes. In July 2001 an expedition, funded by TV station Channell 4 and headed by the well-known maritime investigator David L. Mearns, found the wreck of HMS Hood and recorded it on film. The last survivor, Ted Briggs visited the final resting place of his vessel and placed a plaque in memory of his shipmates. In November 2001, the British government designated the wreck of HMS Hood an official war graveyard. On October 4, 2008 the last survivor of the sinking of HMS Hood, Edward Pryke Briggs died after a long illness at the age of 85.

Definitielijst

- battleship

- Heavily armoured warship with very heavy artillery.

Information

- Article by:

- Peter Kimenai

- Translated by:

- Arnold Palthe

- Published on:

- 23-08-2023

- Feedback?

- Send it!