Introduction

"It is beyond dispute that defence merely postpones the decision, even in the best-case scenario. Victory – in other words: imposing our will on the enemy – is only possible through attack. Even then, it is an age-old tradition for the defender to set up fortifications. If he loses, it is not due to the construction of his fortifications. He finds himself in that defensive position because he perceives himself as weak. Without the defender’s fortifications, the task of the aggressor becomes only easier. We can only hear the voice of the victor after a concluded battle, and no one will grapple with the next problem: how much effort was required for him to achieve this victory?" -Colonel of the Engineer Corps and architect of the Árpád Line, Hárosy Teofil-

The Árpád Line (named after the Grand Prince Árpád, founder of Hungary in the late 9th century) was an almost 373 miles-long Hungarian defensive line in the eastern Carpathians, along the historical eastern border of the Kingdom of Hungary. Due to the fortifications being incorporated into the rugged mountainous terrain, the Árpád Line was considered impregnable. A bloody and arduous battle was fought in the eastern Carpathians between August and October 1944.

Pill-box of the Árpád Line near Synevir village (Transcarpathian oblast, Ukraine). Source: Wikimedia

Background

On November 2, 1938, the ‘First Viennese Agreement’ was signed by Germany, Italy, Hungary and Czechoslovakia, which forced Czechoslovakia to cede the southern parts of Slovakia and Carpathian Ruthenia (roughly the border region between Ukraine, Slovakia and Poland) to the Kingdom of Hungary. This decision granted Hungary the right to regain territories it had lost to Czechoslovakia as a result of the Treaty of Trianon on June 4, 1920, after World War I. Between November 5 and 10, 1938, parts of these territories were peacefully annexed by the Hungarian army.

In March 1939, Hitler had secretly granted Hungary permission to annex the remainder of Carpathian Ruthenia, which had declared itself an independent republic on March 15, 1939. A day earlier, the pro-German First Slovak Republic had already been declared. On the night of March 22 to 23, 1939, the Hungarian army invaded Slovakia and managed to advance 12.5 miles before being stopped by the Slovak army. The annexed territory remained under Hungarian control until the German occupation of Hungary in 1944. This area had a population of 2,633,000 people: 51.4% Hungarian, 42% Romanian, 3.7% German and 2.9% other nationalities.

The eastern Carpathians are characterized by a large number of small and large rivers, streams, valleys and ravines. There are also numerous mountain slopes, and it is a heavily forested area with relatively few paved roads. All of this made the region almost inaccessible for infantry and mechanized troops.

Definitielijst

- infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

Construction

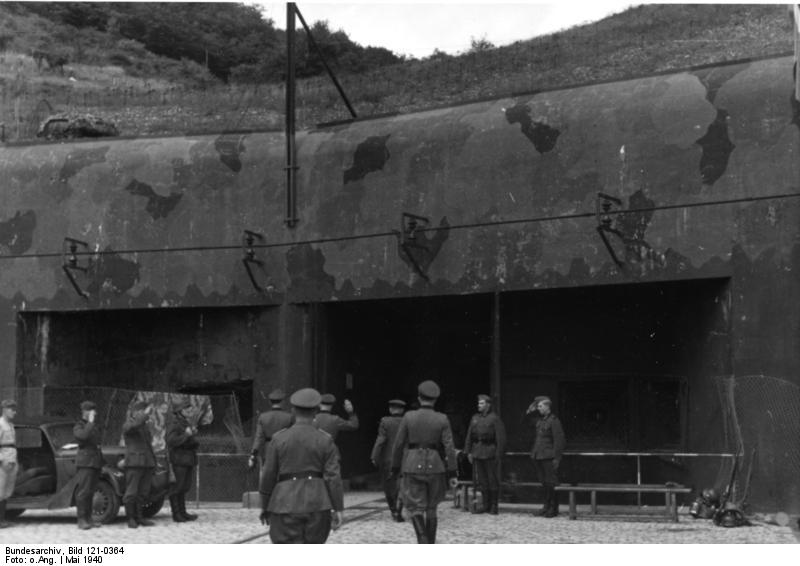

Preparations for a defensive line in the recently annexed eastern Carpathians began in the summer of 1939. It was intended to counter a potential invasion from the Soviet Union and protect the northern border of Hungary. As part of these preparations, studies were conducted on contemporary defensive structures in Europe, such as the Maginot line and the Belgian fort Eben-Emael.

Colonel of the Hungarian Engineer Corps, Hárosy Teofil, was appointed to lead this project. The initial constructions consisted of barracks and water locks and were built in the autumn of 1939. Romani men were used as forced labourers in the process, being housed in several forced labour camps in eastern Hungary which were guarded by the Hungarian army. The first bunkers were built in the spring of 1940. The design of these bunkers was derived from the bunkers of the French Maginot Line, which was considered the most modern defensive line in the world at the time. In the autumn of 1940, a Hungarian commission visited the French and Belgian fortifications and recommended discontinuing the construction of bunkers in the ‘French style’. This advice was followed, and a different concept was adopted.

Around the same time, the so-called 'Erõdítési Csoportparancsnokság' ('H Fortification Group Command') was established to oversee the construction of this defensive line. The plan was to construct a 7485 miles-long defensive line. This process was estimated to take approximately 10 years. The budgets for the project were as follows:

| Period | Amount |

| 1939-1940 | 14,2 million pengő |

| 1941 | 6,8 million pengő |

| 1942 | 19 million pengő |

| 1943 | 67 million pengő |

| 1944 | 67,5 million pengő |

It should be noted that the data for 1943-1944 is misleading due to the inflation at that time.

Consideration was already given in advance to the natural barriers of the mountainous terrain, and efforts were made to utilize them to the fullest. The defensive line was named after the Medieval founder of Hungary and the Hungarian royal dynasty of the Árpáds: Árpád.

The fortifications that were constructed were diverse: (underground) shelters, machinegun nests, anti-tank casemates, water locks, artillery positions, storage facilities, trenches, anti-tank obstacles, and even the conversion of houses and cellars in the surrounding villages to strongholds. Additionally, barbed wire barriers (in some cases electrified) and minefields were laid out. The so-called St. Laszlo fortress largely consisted of fortifications from World War I.

The mountain passes were heavily fortified, and the dams were protected by field positions against attacks from all sides. The fortifications were designed in such a way that the Hungarian army could launch counterattacks to constantly impede the enemy. It was never the intention of the Hungarians to permanently halt the enemy in the eastern Carpathians, but rather to slow down his advance. This was one of the conclusions they drew from observations of other European fortifications and defensive lines.

The defeat of the Axis powers at Stalingrad in February 1943 marked a turning point in World War II and led to an increase in the construction speed of the Árpád Line. In 1944, three additional defensive lines ("Prinz Eugen’’, "Hunyadi", and "Szent László") were constructed to the east of the outposts of the Árpád Line to create a buffer. Delyatin, Nadvornaya, and other locations were fortified. The construction of these defensive lines was eventually halted in the autumn of 1944. At that time, the Árpád Line extended over a length of 600 kilometres: from the Dukla Pass in the west to the Yablunytsia Pass in the east. The defensive line was not continuous but consisted of independent strongholds. Each of these separate strongholds consisted of 10-20 small bunkers surrounded by anti-tank and barbed wire barriers, trenches, and minefields. The garrison ("Fort Company") of such a stronghold consisted of 200-300 personnel. These formations were supported by border guard battalions, which were usually entrenched about 4 to 10 kilometres behind the so-called Fort Companies. They were primarily responsible for the communication lines.

The following two tables provide an overview of the composition of the line in autumn of 1944:

| Type | Quantity/Length |

| Strongholds | |

| Concrete bunkers | |

| Wooden/underground shelters | |

| Open emplacements | |

| Trenches and anti-tank ditches | |

| Anti-tank and personnel obstacles |

| Significant fortified regions | Location |

| Uzsoker-pass | Malomrét Havasköz |

| Verecke-Pass | Vezérszállás Alsóverecke Volóc |

| Tornyai-pass | Ökörmező Felsőszinevér Alsókalocsa |

| Pantir-pass | Királymező Oroszmokra |

| Tatar-pass | Körösmezö Rahó Tiszabogdány |

| Borsai-pass | Vasér Havasmezö Borsa |

| Radnai-pass | Oradna Kisilva Nagyvila |

| Borgoi-pass | Marosborgo |

| Tölgyesi en Békás-passes | Gyergyotölgyes Borszék Palotailva Gyergyobékás |

| Gyimesi-pass | Gyimesfelsölok Kászonujfalu Sepsibükszád |

| Ojtoz-pass | |

| Uz-Tal |

The Arpad Line was manned by the 1st Hungarian Army (13th Infantry Division), the 2nd Hungarian Army, one German division, and the XXXXIX. Gebirgs-Armeekorps.

Definitielijst

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- inflation

- An economic process of sustained increase in general price levels and devaluation of money.(loss of purchasing power)

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Maginot line

- French defence line along the French-German border.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

The Árpád Line in action

On June 22, 1944, the Red Army launched ‘Operation Bagration’ and managed to capture large parts of Belarus, the Baltic States, Ukraine and eastern Poland within a month. In August 1944, the 1st and 4th Ukrainian Fronts reached the borders of the eastern Carpathians, not only making the terrain became more rugged, but also intensifying German and Hungarian defence efforts. At the same time, partisan activity in the Carpathians increased. Soviet Colonel-General Andrei Grechko, commander of the 1st Guards Army, recalled the following:

"As our troops advanced along the slopes of the Carpathian mountain region, the enemy’s defence grew stronger. The inhospitable terrain aided the enemy in establishing a strong defence along the routes of the 4th Ukrainian Front. However, our strong attack managed to slowly push back the enemy between August 6 and 12, 1944, even in this exceptionally difficult environment of the Carpathian mountains. Between August 12 and 15, 1944, our troops were stopped, however, and the enemy was even able to completely halt our best units."

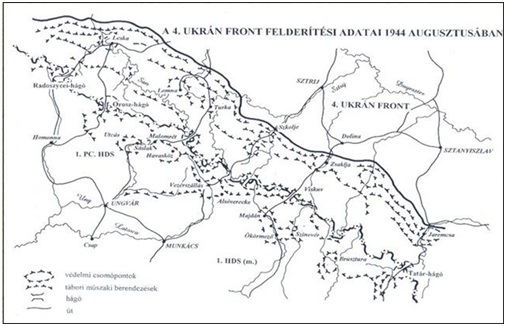

The 1st Hungarian Army underwent reorganisation in early August 1944. Colonel-General Béla Miklós replaced General Ferenc Farkas on August 3, 1944. The 7th Corps was recalled and reunited with this army, while the 6th Corps, under heavy pressure, had to abandon the "Hunyadi" defensive line and entrenched itself in the Tatar Pass.

In mid-August 1944, soldiers of the 4th Ukrainian Front Army entrenched themselves in the eastern Carpathians, while the 1st Hungarian Army completed its reorganisation. Commanders on both sides took advantage of this temporary pause to supply troops and weaponry. The 1st Hungarian Army received three new infantry divisions and the XXXXIX Gebirgs-Armeekorps. Efforts were also made to establish supply lines. At this time, the Red Army was still facing the outposts of the Hungarian defence at Hunyadi, and the main issue the Soviets grappled with was a shortage of manpower. The Hungarian 3rd Corps defended the Uzsok Pass, the 7th Corps held on to the "Hunyadi Line" near the Tornyai and Verecke Passes, while the 6th Corps defended the Tatar Pass. By August 20, 1944, the 1st Hungarian Army had approximately 200,000 troops at its disposal (including 22,000 German troops).

On August 20, 1944, the 2nd and 3rd Ukrainian Fronts launched the so-called Iasi-Kishinev operation, aimed at encircling the Carpathian mountain region from the south. By this time, the Red Army had already managed to bypass the Polish section of the Carpathians from the north. It was due to this situation that the 4th Ukrainian Front had to continue exerting pressure on the Hungarian and German defenders. This was not an easy task, as Colonel-General Andrei Grechko wrote:

"Advancing in mountainous terrain is one of the most challenging military activities. The formation, extremely limited and deeply divided, along with stretched supply lines, make frontal advancements almost impossible or even completely impossible. The organization of the signalling system, cooperation, and protecting your flanks becomes very complex as a result. Due to the extensive fortifications in narrow valleys, frontal attacks were ruled out. Continuing the offensive is only possible with flanking manoeuvres, bypassing fortifications through areas were paths exist…"

On August 21, 1944, officers of the 1st Hungarian Army convened to determine the line the army should hold during the winter. During this discussion, the Szent László Line was designated, but the German high command prohibited the 1st Hungarian Army from taking even one step back.

The pro-German Romanian government was overthrown on August 23, 1944, by King Michael of Romania, who sought to align his country with the Allies. As a result, the southern flank of the Árpád Line bordering Romania came under heavy pressure. The Hungarian army launched an attack on the southern passes in Romania, but were repelled. On August 26, 20-30 Soviet tanks crossed the Hungarian border from Romania at the Uz Pass. The Hungarian defenders were driven out around noon when they ran out of ammunition, but due to the narrow gorges in this valley the tanks could be easily destroyed by Stuka dive-bombers. On August 28, the Romanians and Soviets launched a new attack on the pass. The fighting for the pass would continue for another three weeks before the Red Army and the Romanian army gained control of the area. Desperate attempts by Colonel-General Béla Miklós to persuade his superior, the commander of the 4th Panzer Army General Gotthard Heinrici, to allow the 1st Hungarian Army to withdraw towards the Tisza River fell on deaf ears.

The 4th Ukrainian Front did not manage to reach the Árpád Line, let alone break through it, in September. On September 9, this front launched the so-called ‘Carpathian-Ungvar operation’. Between September 9 and 28, 1944, the 1st Guards Army and the 17th Guards Infantry Corps were able to cross the main mountain range of the Carpathians and occupy the Radnai and Orosz passes, thereby reaching the Czechoslovakian border. These two formations advanced approximately 2.5 - 4.3 miiles, but suffered significant losses. Soviet forces utilized the few mountain paths available during their advance, and often had to create new paths with the resources at hand. In October 1944, the 4th Ukrainian Front received orders to continue the offensive. The objective was to cross the Carpathians and reach the sectors of Ungvar and Munkacs. The 17th Guards Infantry Corps advanced through the Tatar Pass towards Korosmezo-Raho-Maramarossziget. The Korosmezo fortress was one of the strongest mountain fortifications of the Árpád Line. This fortress consisted of 19 strongholds, each consisting of two to three open emplacements and machine gun nests. Many of these strongholds were supported by artillery batteries and tactical headquarters.

The 4th Ukrainian Front faced stubborn resistance from the defenders, who effectively utilized the forested mountainous terrain and obstacles in the passes. The battlefield was characterized by attacks and counterattacks, and land that was constantly captured and recaptured. Nonetheless, the 1st Hungarian Army suffered significant losses west and south of Korosmezo as the 17th Guards Infantry Corps outflanked the Hungarian positions in the Uzsok Pass from the south and captured Stavnoje. This forced the Hungarians to withdraw from the fortified region of Korosmezo to Raho and Maramarossziget, after which the 17th Guards Infantry Corps captured the Verecke Pass and advanced several kilometres southward. On October 15, 1944, the 17th Guards Infantry Corps began pursuing the retreating Hungarian army. Three days later, this corps captured Maramarossziget and made contact with the 2nd Ukrainian Front. The 2nd Ukrainian Front played a significant role in the successes of the Red Army in the eastern Carpathians, reaching the sectors of Debrecen and Nyiregyhaza on October 15, threatening the supply base of the 1st Hungarian Army. It because because the 2nd Ukrainian Front exerted pressure on the southern flanks of the Árpád Line, putting Hungarian and German troops at risk of being encircled, that the Axis powers decided to withdraw. This allowed the 4th Ukrainian Front to occupy the positions of the Árpád Line.

At this point, many Hungarian soldiers and their officers had become demoralized, and on October 16 the commander of the 1st Hungarian Army, Colonel-General Béla Miklós, and his chief of staff deserted to the Red Army, encouraging his staff members and soldiers to do the same. Approximately 20,000 Hungarian soldiers followed their example and were absorbed by the 4th Ukrainian Front. For this reason, the German high command decided to expedite the withdrawal of this army. The Hungarians were trapped between the Germans and the Red Army.

The easternmost point of the Árpád Line (the Dukla Pass, now in northeastern Slovakia) saw heavy fighting between September and October 1944, which concluded in a bloody, indecisive battle on October 28, 1944. Shortly thereafter the German army withdrew from the region. The Hungarian army also retreated from the last mountain positions in the Carpathians, after repelling multiple Soviet attacks and inflicting heavy losses on them.

On December 29, 1944, Budapest was encircled by the Red Army and the Romanian army. The city would ultimately fall on February 13, 1945.

Definitielijst

- infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- machine gun

- Machine gun, an automatic heavy quick firearm.

- mid

- Military intelligence service.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Aftermath

While the Árpád Line can be seen as a powerful piece of military architecture, it also had its weaknesses, as Colonel-General Andrei Grechko wrote:

"The weak point of the enemy Carpathian defence was that the positions were incomplete and that some inter-sector areas along the main slopes, between certain important directions, had no fortifications."

For two months, the Hungarians and Germans managed to hold back the Red Army in the Carpathians. However, when Romania sided with the Allies on August 23, 1944 (threatening the southern wing of the Árpád Line), and as a result the 2nd Ukrainian Front could pass through the southern Carpathians and break through the southern sectors of the area, the defenders had no choice but to abandon their positions to avoid encirclement. It did not take long after that for the 1st Hungarian Army – and thereby the Árpád Line – to collapse.

Still, the Árpád Line had managed to fully entrap the 4th Ukrainian Front. If Romania had not switched sides on August 23, 1944, and the 2nd Ukrainian Front had not pressured the southern flanks of the eastern Carpathians, the situation would have likely looked different. A scenario in which the Red Army would have been entrenched in the Carpathians for the entire winter is not unimaginable.

Definitielijst

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

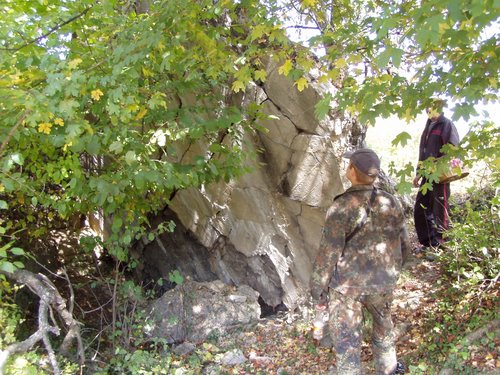

The Árpád Line in the present day

After World War II, the Árpád Line was mostly dismantled by Soviet, Romanian and Hungarian sappers. Thus, there are few bunkers left which can be visited in an intact state. One of the bunkers can be visited as a museum nowadays. The majority of the Árpád Line in the present day is located in the Zakarpattia Oblast in Ukraine. The following fortified regions have remained relatively untouched and are therefore most worthy of a visit:

| Fortified region | Amount of bunkers |

| Verecke Pass | |

| Korosmezo | |

| Tornyai Pass | |

| Uzsoki Pass | |

| Ojtozi Pass |

The Soviet soldiers and partisans that perished in the battle for the eastern Carpathians are buried in the following places, among others: Perechyn, Mukachevo, Vynohradiv, Beherove, Chop and Sighetu Marmatiei.

Information

- Article by:

- Kaj Metz

- Translated by:

- Kamran Gasimov

- Published on:

- 19-01-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Sources

- The Arpad-linie

- Military History - Northeast Slovakia

- Defence fortification system "Arpad line"

- De gerst-LINE PROFESSIONAL EYE (1940-1944)

- Wikipedia

- Az áttörhetetlen Árpád-vonal

- Árpád vonal

- Az Árpád-vonal déli szárnya

- Axis History Forum

- SOVIET MILITARY OPERATIONS AND OCCUPATION OF HUNGARY IN 1944 - 1945

- Hungary’s Roma community marks 70th anniversary of Roma Holocaust