Operation Razzle

Introduction

In the spring of 1940, Germany had defeated France, Belgium, The Netherlands and Luxembourg and had driven the British forces out of Western Europe. The threat of a German invasion of Britain was growing and the British were desperate to bring the war directly to Germany itself. RAF Bomber Command was the only force within the British armed forces that could attack Germany and there was a lot of debate how it was best employed. Its objective changed frequently in 1940. One of the lesser known campaigns of that summer was Operation Razzle, a series of fire-raising attacks on the German harvest and forests.

Western Air Plans

The idea to burn forests and crops in Germany came from the First World War and it was still part of the Western Air Plans which were formulated in 1936. These plans (16 in total) listed strategic targets for attack in case of a German offensive in Western Europe. Western Air Plan 11 existed of setting fire to ripening crops and woods in an attempt to hit Germany’s food supplies. It would be an extension of the blockades carried out by the Royal Navy to cut off the food supplies. The idea was discussed in the War Cabinet. It was believed that such attacks and the blockades could initiate a corn famine in Germany. The German corn crops would be very vulnerable to attacks owing to the large areas under corn unbroken by any hedges or ditches. The fire-raising attacks had to be carried out over forests like the Black Forest as well. It was believed arms and other military stores were being concealed here. It would be essential to carry out the attacks on a very large scale, using all available aircraft.

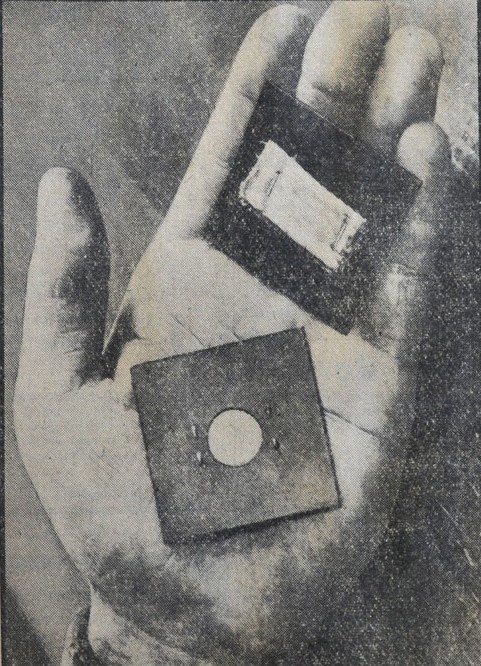

Scientist developed an incendiary device for the attack which was called ‘razzle’. These were phosphorus pills covered with gauze and inserted between square pieces of celluloid. They were kept wet in sealed cans. After being dropped they would dry out on the ground, instantaneous combustion would take place and fire would be started. The ‘razzles’ had to be dropped through the flare chute of the aircraft, like leaflets on a nickeling operation. The art of dropping this was called ‘razzling’. Successful trials were carried out and it was calculated that 7,000,000 ‘razzles’ could be produced a week.

But there was a lot of debate about how Bomber Command was best employed in a strategic air offensive against Germany. With the growing prospect of air attacks by the Luftwaffe and an invasion of Britian is was stressed that Bomber Command’s main objective would remain to attack German aircraft factories and assembly plants, shipping and the oil industry. But the War Cabinet authorised Air Marshal Charles Portal to carry out Operation Razzle when the situation permitted. However, no special missions were ever planned for ‘razzling’. Crews were detailed to bomb a primary target and their aircraft carried ‘razzles’ as well. They had to arrange their routes to a target so that they passed over fields or forests in Germany when they could be dropped out at will.

Guy Gibson was flying with No.83 Squadron at that moment and he also caught the rumour on operation Razzle: "Word got around that a lot of Germany’s armament reserves were being stored in scattered hangars in the Black Forest. A plan was accordingly set afoot to destroy these and other weapons and also Hitler’s wood supply. Scientist put their heads together and soon the weapon was evolved." Gibson would not take part in operation Razzle. The squadrons from No.3 and No.4 Group were assigned to carry out the razzling during their operations.

The raids

The first operations targeting crops and forests were carried out in June 1940. On the night of 11/12 June 18 Wellingtons dropped incendiary bombs over the Black Forest. On the night of 14/15 June 1940 three Wellingtons of No.9 Squadron and two Wellingtons of No.214 Squadron had to drop their incendiaries over the Black Forest.

On the night of 11/12 August 1940 eight Whitleys of No.10 Squadron were ordered to destroy the oil refinery at Gelsenkirchen (primary target) and to set fire to forests in the southwest of Germany. At RAF Leeming the crews were called into the station operations room that evening. Wing Commander Sidney Bufton briefed them for the upcoming operation. Every aircraft carried their bomb load for the primary target as well as fifty tins of pellets ‘razzle’. As the crews of 10 Squadron were to drop ‘razzle’ for the first time a demonstration was given how to use the pellets. The first wireless operator had to open the cans and pour the contents down the flare chute. One of the aircraft was flown by the crew of Flying Officer Henry. His wireless operator – Sergeant Donnely – recalls: "Also carrying the new secret weapon – ‘RAZZLE’. […] We had been detailed to attack this target then to proceed to the Black Forest to drop ‘Razzle’. As this was to be the first use in action and we were one of the ‘guinea pig’ crew. I made it my business to find out what it was all about from our armament Chiefy, especially as it would be my task to off-load it. The aircraft had been fitted with wooden racks inside the fuselage containing forty-eight of the sealed cans. The method of despatch was simple; rip off the tin-foil seal on top of the can and pour the contents down the flare chute. We were warned to ensure that all the leaves left the aircraft and, in the event of any remaining, we were instructed to use the DIY fire prevention kit – the garden syringe."

Donnely and his crew flew Whitley P4953 on this operation. "We dropped our bombs and got away unscathed then proceeded towards the ‘RAZZLE’ dropping area. The aircraft stooged around unmolested while I diligently poured the leaves down the flare chute and after the last can had been emptied I used my shaded hand torch to ensure that none of the ‘RAZZLES’ remained in the aircraft before returning to the cockpit to resume my wireless operating. […] We landed back at base at 05.25 hours and taxied back to dispersal basking in the relief that we’d made it once again. Our complacency was rudely shattered by a call from George Dove in the tail turret reporting that the fabric on the elevators was burning! We lost no time in getting to dispersal where our ground crew extinguished the fire. Some of the Razzel pellets had lodged in the control hinges and had dried out during the return flight, thus causing the fire."

In early September more operations included ‘razzling’. On the night of 2/3 September 18 Wellingtons from No.149 and No.214 Squadron dropped incendiaries and ‘razzles’ over the Black Forest and the forests of Thuringia. Flight Lieutenant Keith Kaufmann – an Australian pilot flying with the RAF – piloted Wellington T2470 of No.214 Squadron. He wasn’t very much impressed by the target for this operation: "we didn't hit much - we hit a lot of fields and knocked some crops around."

Berlin and Magdebug were on the ‘visiting list’ for the night of 4/5 September, when six aircraft were sent to each target. The returning No.51 Squadron Berlin raiders also dropped ‘razzles’, but lost Pilot Officer Taylor’s Whitley P4973, which ditched in the North Sea off Texel island. Five of the crew were rescued by 5./Seenotstaffel and taken prisoners of war. The 2nd pilot – Sergeant Jones – went down with the aircraft. The squadron sent 9 Whitleys to Regensburg on the next night and these aircraft alsa carried ‘razzles’. Eight Wellingtons of No.214 Squadron ‘razzled’ targets in the Harz.

A newspaper article on the ‘razzle’ operations was published in The New York Times of 5 September: "Great fires are sweeping through Germany’s forests to-day after the R.A.F. bombing of military objectives concealed in the forests early yesterday morning. Some of these secret targets were in the Grünewald Forest, north of Berlin, and subsequently fires were visible from the city. Explosions also were caused when secret targets in the Harz, Thuringen and Black Forests also were bombed. Pilots returning from these raids reported fierce blazes, seen from 100 miles on their homeward flight."

A few more operations followed in late September. Aircraft of No.51, No.77 and No.78 Squadron attacked targets in the Berlin area on the nights of 23/24 and 28/29 September. On their return they were to drop ‘razzle’ in the area between Bremen, Hamburg and Hannover. On the night of 16/17 October crews returning from operations to Merseburg had to drop ‘razzles’ over the Harz forest.

Lack of success

Large numbers of ‘razzle’ were dropped over various targets in Germany but there is no evidence that these attacks did any significant damage to either German harvest, forests or any secret armament dumps. The weather in northern Europe seemed to be unfavourable for this kind of operations as well. There was, however, mention of the effect of Operation Razzle in an edition of the Neue Frankfurter Zeiting. According to this newspaper some souvenir-hunting German civilians took some of the ‘razzles’ home and received an unpleasant shock. This news must also have reached England as both Donnely and Gibson make mention of it in their memoirs. Donnely: "The only damage caused by these ‘Razzles’ was to unsuspecting German souvenir hunters who put the leaves in their trouser pockets." Gibson mentions: "Oscar, Rossy and I were having a good laugh about this story. [..] One pilot made a navigational error while flying above the cloud and dropped his razzles in the middle of Bremen. The citizens of that city, having received a few leaflets the night before, thought this was more British propaganda coming down from the skies; knowing full well that the Gestapo’s eyes were everywhere watching their movements, they stealthily crept along the streets, picked up the razzles, stuck them in their trousers pockets and took them home to read.. The results must have been embarrassing."

Besides the lack of success of Operation Razzle priorities in the employment of Bomber Command’s aircraft also shifted. There was an urgent demand for the bombers to attack the concentrations of barges which were built up by the Germans in ports in western Europe. These barges were concentrated in preparation of a possible German invasion of Great-Britain.

Definitielijst

- Bomber Command

- RAF unit which controlled strategic and sometimes tactical bombing (as in Normandy)

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

- incendiary device

- Incendiary ammunition especially developed to set fire. Filled with napalm, thermite of white phosphorus. Sometimes equipped with a timer with explosive load to hinder the extinguishing.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Luftwaffe

- German air force.

- Marshal

- Highest military rank, Army commander.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- RAF

- Royal Air Force. British air force

- Squadron

- A military unit in the Belgian navy usually six to eight small ships operating together under one command. The smallest military unit in the Dutch air force of about 350 men. In most countries is the designation of a military unit thesize of a company. It is either an independent unit, such as a battery, or part of a bigger Calvary unit. In the air force it is the designation of a unit of aircrafts.

Information

- Article by:

- Pieter Schlebaum

- Published on:

- 20-05-2024

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related books

Sources

- G. L. DONNELY, The Whitley Boys, Crecy Publishing, 1991.

- MIDDLEBROOK, M. & EVERITT, C., The Bomber Command War Diaries, Midland Publishing, 2011.

- 10 Squadron Operations Record Book

- 51 Squadron Operations Record Book

- 77 Squadron Operations Record Book

- 78 Squadron Operations Record Book

- 149 Squadron Operations Record Book

- 214 Squadron Operations Record Book

- Memoirs of Keith Kaufmann