The eastern Netherlands liberated from Germany

The period of static actions along the winter front of the Meuse and Waal ended for the First Canadian Army on February 8, 1945. For the Canadians, operation Veritable began, an Allied pincer movement, meant to force the German troops out of the area between the Rhine and the Ruhr. Together with the British XXX Corps, the First Canadian Army advanced from the north, while American divisions, with Operation Grenade, made a pincer movement from the south. The Germans tried to withstand these operations by piercing the Rhine dikes and by blowing up the closing mechanism of one of the Ruhr dams, so that there was no way to stop the water flow from the reservoir. During this operation, the Canadian 2nd and 3rd divisions would operate on the left flank of the British. The Germans had also flooded the land alongside the Waal and Rhine rivers, making the Canadian advance more difficult. After heavy fighting in the Reichswald, the Canadians eventually reached their objectives on the banks of the Rhine on March 10 1945.[1]

The offensive was resumed in February 1945, with the Canadians advancing further along the Rhine to the cities of Wesel and Xanten. Next, on March 9, 1945, Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery issued several orders to the Canadian general Harry Crerar. The Canadians were to liquidate the German positions at the IJssel River – part of the Siegfried Line (Westwall in German). The cities Zutphen and Deventer were springboards to the Veluwe [a ridge of forested hills] and these cities had to be taken. From the Wesel-Emmerich line, the first assault wave took place. After a horrific artillery bombardment by the Germans at Rees on March 23, 1945, the British and Canadians crossed the Rhine at Rees during Operation Plunder and shortly after that at Wesel. On March 27, Montgomery added an order that the eastern Netherlands must be liberated and that the Canadians should advance to the German North Sea coast. Finally, on March 28, the British and Canadians managed to break through the German defences, exactly on the dividing line between the 6. Fallschirmjäger- and the 8. Fallschirmjäger-Divisions.[2]

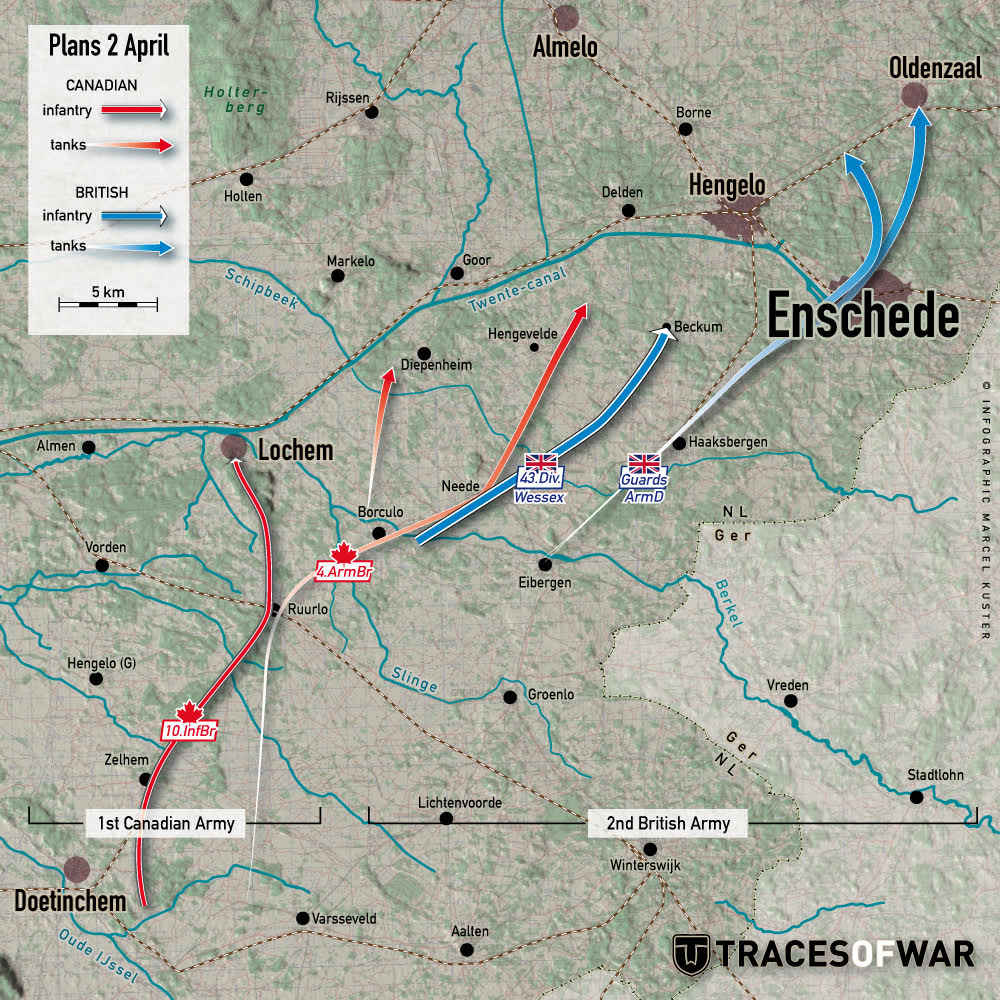

After this Allied breakthrough, XXX elements of the British Army pushed on, entering Germany just north of Enschede after liberating a narrow strip of the Netherlands. That liberation ended the work of the British XXX Corps in the Netherlands. Only the 49th (West Riding) Infantry Division would remain for deployment in the Overbetuwe area. Simultaneous with the operations of the XXX Corps, the Canadian Armoured Division and the Second Canadian Infantry Division had come into action. On April 1, 1945, Zelhem was chosen as a starting point of the triangle formed by Ruurlo, Hengelo (province of Gelderland) and Vorden. The British had already liberated some parts of this triangle, but the Canadians took over this section from them.[3]

Definitielijst

- Fallschirmjäger

- German paratroopers. Part of the Luftwaffe.

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- liquidate

- Annihilate, terminate, destroy.

- Marshal

- Highest military rank, Army commander.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- Westwall

- Also known as Siegfried Line, the German defence line along the German-French border.

German defence, spring 1945.

In the German headquarters of Oberbefehlshaber West, there was concern about the ensuing defensive battles. The German generalfeldmarschall Gerd von Rundstedt had three army groups at his disposal, for the defence of the western front: * the 25. Armee; * the forces of the Wehrmachtsbefehlshaber in den Niederlanden, [Wehrmacht Commander in the Netherlands], General Friedrich Christiansen; and the 1 Fallschirm-Armee. This group eventually became partly responsible for the defence of the Twente-Canal. The three army groups consisted of nine divisions, which had suffered heavy losses in previous battles, causing the morale and combat value to diminish considerably. The first Fallschirm-Armee was placed between Emmerich and Duisburg and consisted of three army corps, four Fallschirmjägerdivisionen and two infantry divisions.

After the spectacular March 1945 crossing of the Rhine at Wesel, the Germans tried to stop the Allied attack with counterattacks, but this attempt did not have any effect. On April 1, the Luftwaffe general Kurt Student appeared at the headquarters of Heeresgruppe H in Almelo to prepare a counterattack. A short inspection by Student proved that this was out of the question. Nonetheless, he decided to form a new Armeegruppe ‘Student’, between the 25th Armee and the First Fallschirm-Armee, whose fighting formations of the LXXXVIII Armeekorps that fought east of the IJssel River and units of the II Fallschirm-Korps, together with General Christiansen’s guard units, were placed under Student’s command.

On April 3, at his headquarters in the German town of Lingen, Student received a new order: to hold out at the Twente Canal and to restore the connection with the Fallschirmjäger Korps, whose left wing was formed by the 8. Falschirmjäger-Division. However, holding out behind a front obstacle 40 km wide (the Twente Canal) could be quickly overcome by the enemy with their technical possibilities, but could not be achieved with the exhausted divisions. German 6. Falschirmjäger-Division was responsible for the defence of the Twente Canal up to Hengelo on the bank and north, from there. In this way, the German division covered the open flank up to the vicinity of Almelo. The commander of this division was Generalleutnant Herman Plocher, who had established his headquarters in the village of Holten and Dalfsen.

However, for the 6. Fallschirmjäger-Division there were some advantages. The Twente Canal, which in various places was 60 meters wide, formed a natural obstacle and therefore formed a good line of defence. In addition, the division consisted mostly of young officers and men who were extremely fanatic and fought persistently. All of this meant it took another ten days before the whole of Twente was liberated.

Definitielijst

- Armeegruppe

- Usually consisted of two or three neighbouring Armees, sometimes German and Axis-allied Armees. One Armee HQ, usually the German, temporarily became the commanding HQ of the other Armees. An Armeegruppe would always be subject to a Heeresgruppe. Later in the war the size of an Armeegruppe or Panzergruppe varied significantly. From 1943 onwards an Armeegruppe could be the size of an Armee or just the size of a corps.

- Fallschirmjäger

- German paratroopers. Part of the Luftwaffe.

- Heeresgruppe

- The largest German ground formation and was directly subordinate to the OKH. Mainly consisting of a number of “Armeen” with few directly subordinate other units. A Heeresgruppe operated in a large area and could number several 100,000 men.

- infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- Luftwaffe

- German air force.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

The Canadian combat groups Lion and Tiger

Lieutenant-General Guy Simonds wanted to break through the German front with a narrow, concentrated thrust. To the righthand side, the Fourth Canadian Armoured Division would advance to the northeast. The Second Canadian Infantry Division would commence the attack in the direction of Zutphen, and at the same time, the Third Canadian Infantry Division, to the left, would attack in the direction of Wehl, (in the province of Guelre, near Doetinchem). After capturing Wehl, this division would also concentrate on Zutphen. To prevent the various divisions and brigades from losing contact, the Seventh Brigade of the Third Canadian Infantry Division was deployed to advance west of Wehl to Zevenaar, Didam and between Emmerich and Arnhem. Here, they expected to meet the 49th British West Riding Division. This division would cross the Lower Rhine and form a bridgehead at the northern side of the river, immediately east of Arnhem, to clear the rest of the eastern sector in the Betuwe.

Despite these risks, Simonds managed to keep his First Canadian Infantry Division in reserve until Zutphen was captured. This division could eventually advance in a westerly direction to Apeldoorn during Operation Cannonshot, the crossing of the IJssel River via Gorssel and Wilp. The attack was launched on April 2, 1945, under the command of Simonds and General Charles Foulkes. Within the 21st Army Group, it was doctrine to operate in combined tank-infantry battle groups so the attack was launched according to 'Monty's Functional Doctrine'.[4] The 4th Canadian Armoured Division was therefore divided into two mobile battle groups, which would operate individually. The Canadian armoured divisions consisted of two brigades, the infantry divisions of three brigades. One brigade consisted exclusively of tanks and armoured vehicles, and the second brigade exclusively of infantry.

Experience with previous operations showed that a rapid advance over open countryside with tanks swiftly cleared German resistance. In addition, a mechanised infantry battalion was added to the armoured brigade. The infantry was equipped with carriers to keep up with the tanks during the advance. Reality proved, however, that European terrain was unsuited for such tactics. The numerous canals and bridges proved to be a hindrance for tanks.

The assault group Lion would be the first of the division to start the operation and advance to the Twente Canal. This assault group was led by commander Jim Jefferson of the 10th Canadian Infantry Brigade. The assault group consisted of a number of the Governor General’s Foot Guards tanks and a reconnaissance unit of the South Alberta Regiment of the Fourth Canadian Armoured Division. The Algonquin Regiment and the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders Regiment would be deployed exclusively as infantry. In addition, Jefferson had at his disposal the heavy machine guns of the New Brunswick Rangers Anti-tank Battery. The Canadian Field Ambulance and the Ninth Canadian Field Squadron engineers supported the Lion assault group.

Simonds considered the assignment of the assault group straightforward since the British 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division (129th Infantry Brigade) nearly controlled Lochem, a village along the Twente Canal. As soon as assault group Lion had formed a bridgehead over the Twente Canal, the assault group Tiger, under the command of Brigadier Robert Moncel, would continue the advance east, in the direction of Delden and Born.[5] The priority of the operation was to form a bridgehead on the south side of Delden, to provide cover for the operation that would enable the laying of a bridge so that they could move from there to Almelo. After this, according to Simonds, the division had to advance as far as possible. Moncel had two armoured regiments at his disposal, The Grenadier Guards and the British Columbia Regiment. The Lake Superior Regiment (Motor) and Lincoln and Welland Regiment served as infantry support. The mechanised artillery of the 23rd Canadian Field Regiment, the 96th Canadian Anti-Tank Battery and the 12th Canadian Field Ambulance supported the Tiger battle group.

Definitielijst

- Brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- Regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Squadron

- A military unit in the Belgian navy usually six to eight small ships operating together under one command. The smallest military unit in the Dutch air force of about 350 men. In most countries is the designation of a military unit thesize of a company. It is either an independent unit, such as a battery, or part of a bigger Calvary unit. In the air force it is the designation of a unit of aircrafts.

The Lochem bridge blown up by Germans

Soon, the Lion assault group could advance toward Lochem, where they reached the British positions. However, the assault group took the position of the British only at 16:30 hours. The bridges across the Twente Canal were already blown up. Therefore, Jefferson ordered the South Alberta reconnaissance squadron, equipped with the light Stuart V1 tanks, to reconnoitre another route. With his two Stuart tanks, Sergeant Tom Patterson drove about two kilometres going west from Lochem; then, he turned on a road going north. This road ended at a bridge across the Twente Canal, near Klein Dochteren. This route was crossed by a brook called "the Berkel". The Sergeant found an intact bridge across the Berkel, but mines were attached around the bridge.[6] The crews of the Stuart tanks got out of their tanks to find the mines. They nearly finished this difficult job, when a German on a motorcycle approached the bridge. Alarmed by the sight of the Canadians, he made a sharp turn before the men could open fire on him.

After clearing the mines, Patterson continued the exploration along the narrow road towards the bridge across the Twente Canal. This bridge seemed undamaged, and the Stuart tanks cautiously drove towards it. When Corporal Jimmy Simpson slowly drove his tank up the embankment, a German anti-tank gun fired on his light reconnaissance tank. The tank was knocked out and a soldier was badly injured. Because the remaining reconnaissance unit was pinned down by heavy fire, Patterson called for reinforcements.[7] Lieutenant Colonel "Swaty" Whitherspoon received the message and sent South Alberta C-squadron as reinforcement. Lieutenant Bill Luton’s No. 1 Troop served as a rescue mission, while the other troop with tanks was retained to transport the infantry.

The tanks would have to drive single file over the narrow road to the bridge because the shoulders were too soft for the heavy tanks. Luton did not wait for the infantry and went with his tanks to a high bank in front of the bridge, which offered an excellent cover for the Germans on the other side of the canal. As he slowly advanced up the bank so that only a little piece of the tank’s top was visible above the dike, there was a resounding explosion. Several pieces of the bridge flew into the air.[8] Disappointed, Luton stood looking at the rubble of the essential bridge. Brigadier Jefferson now realised that no usable bridges were available in the area. The Lion assault group was disbanded and the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders and the South Alberta occupied Lochem and the Algonquin Regiment occupied the high ground immediately south of the village.

The citizens of Lochem were ecstatic with the liberation of their village and, came out of their houses to greet the Canadian liberators, with the Germans still entrenched on the other side of the Twente Canal, and the area still under fire from machine guns and artillery. The Argyll’s War Diary states the following about the liberation of the village:

"Lochem was the largest and most attractive village we liberated in the Netherlands. It was a pity that we could not share in the festivities of the local population. Our role as infantry was purely operational."[9]

The Regiment estimated the German strength on the other side of the Twente Canal at approximately 300 men.[10] The company commanders of the Algonquin Regiment would outline the next steps from an observation post in an old leather factory.[11] The complete plan of the division was focused on crossing the Twente Canal near Lochem. The Agonquins were responsible for crossing the canal with assault boats to form a bridgehead on the north bank. Such an action, if taken, would probably end in a massacre, of which the Regiment was aware. Fortunately, the commander of the Fourth Canadian Armoured Division, Major-General Chris Vokes, had issued an order to drop this original plan.

He decided to divert the Tiger assault group via Diepenheim, a village, approximately six kilometres northeast of Lochem and one kilometre from the Twente Canal. Here, Brigadier Moncel had to wait until the British 43rd Division had launched the attack in the direction of the Twente Canal and had formed a two-kilometre bridgehead, from Delden in the west to Hengelo in the east. Once the British reached the other side, they should have been able to secure the attack on Borne and the flank of the Tiger assault group during their attack op Almelo. Unfortunately, the British advanced at a snail's pace.[12]

Definitielijst

- infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- Regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

- squadron

- A military unit in the Belgian navy usually six to eight small ships operating together under one command. The smallest military unit in the Dutch air force of about 350 men. In most countries is the designation of a military unit thesize of a company. It is either an independent unit, such as a battery, or part of a bigger Calvary unit. In the air force it is the designation of a unit of aircrafts.

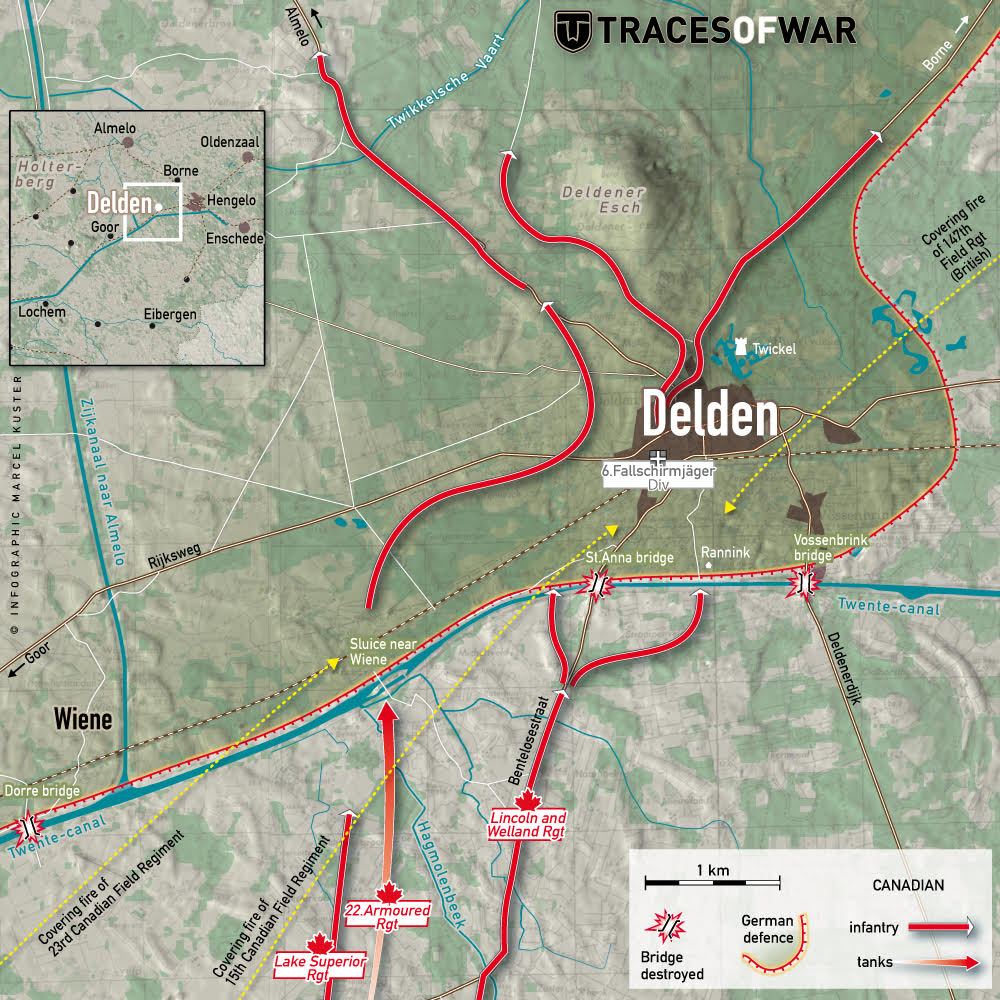

Advance slowed at the Wiene and Delden locks

On April 1, 1945, around 09:00 hrs, the British Royal Dragoons did a recce towards the Wiene locks.. Here they discovered a passage of 1,8 metres wide across the lock. It was clear that the lock could be crossed only by infantry, not tanks. After this, the British 12th King's Royal Rifle Corps, the Sherwood Rangers Yeomanry and the 147 Field Regiment Royal Artillery were ordered to capture the Oeler Bridge and the St. Anna Bridge. At 12:45, the 12th King’s Royal Rifle Corps was ordered to form a bridgehead on the opposite side of the Twente Canal. Once the first soldiers descended the canal dike to the bank, they were fired upon with deadly precision by four German machine guns. Also at the Wiene lock, the advance came to a standstill. German snipers had entrenched themselves in the lock towers, and the Germans fired with artillery and mortars that stopped the attack at 14:00 hrs. The Battalion of the 12th King's Royal Rifle Corps was spread out along a very wide front of the canal for the remainder of the day and night.[13]

Since the British advance was progressing too slowly, Vokes decided to take matters into his own hands. On April 2, around 23:45, he sent Moncel a message that if the British did not advance fast enough, Moncel would be responsible for a crossing of the Twente Canal to create a bridgehead on the other bank. Then, Vokes sent 36 assault boats to the position of the Lincoln and Welland Regiment, which the units involved could use for the attack. On April 3, Vokes gave the order to Moncel to send the "Lincs" at 21:00 hrs. to the destroyed St. Annebrink bridge opposite Delden. In the meantime, Moncel had already started the operation at 04:00. He ordered the commander, Colonel Robert Angus Keane of the Lake Superior’s, to send a patrol to the Wiene locks. These locks were located approximately half a kilometre west of Delden. If the patrol would be successful in reaching the opposite bank and form a bridgehead, then it would be reinforced by a company of around 200 men.

Moncel assumed the locks would offer the best opportunity to cross the Twente Canal. His engineers warned him that building a Bailey bridge across the Twente Canal would take at least 14 hours. Lieutenant Bruce Wrights of No. 13 Platoon of the C-company received the order to form a patrol with the best scouts. Cautiously, the patrol crept in the direction of the lock, while, keeping in close contact by using a radio set. They took advantage of a thick fog and sneaked over the low ground south of the canal. Near the Wiene lock, is the Twente Canal between two high embankments. This made the approach easy, but it was practically impossible to observe possible enemy positions. Slowly, the lock appeared out of the thinning fog, but then the Germans noticed the patrol. They opened fire with machine guns and mortars that forced Wright to withdraw and observe the area around the lock.[14] After this, Moncel realized that the crossing would not take place without a fight.

On April 3, the same day, around 11:00 A.M., Moncel held a meeting. It was decided that a company of the Lincoln & Welland Regiment, would attack with assault boats, on both sides of the destroyed bridge near Delden. The Lake Superior Regiment would carry out a direct attack on the lock near Wiene. Moncel heard that the lock had been lightly damaged, but he hoped that the lock could be used as an emergency bridge[15]

Definitielijst

- infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- Regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

The attack with assault boats

Vokes ordered an attack on April 3, around 7:00 p.m. Commander Coleman of the 23rd Canadian Artillery Field Regiment (Self-Propelled) was shocked by Vokes’ decision.[16] He had a mere seven and a half hours to get everything ready. Naturally, his men would carry out everything without grumbling. As soon as it was clear when the assault companies would reach the northern bank of the Twente Canal, Coleman could devise a plan for an artillery barrage. Thirty minutes before the attack began, artillery fire would be aimed at the German targets. In addition to the explosive grenades, smoke grenades would be fired to mask the attack of the assault boats.

C-company, led by Major Jim Swayze would cross on the right of the Delden bridge with the boats, Major John Dunlops C-company would cross on the left. Each company had 7 assault boats at its disposal. When both companies had formed a bridgehead, D-company, led by captain T.F.G. Lawson would launch the attack on the road north of the railway line, which ran for about 200 metres parallel to the Twente Canal. Major Martin’s B-company would continue the attack from the C-company bridgehead.

The attack began around 4:46 p.m. on April 3.[17] The Lincs had been well-trained for a boat assault. First, men equipped with machine guns would cover the canal dike of the Twente Canal at the crossing points. Then, groups composed of the reserve companies would drop the boats in the water. When the boats were ready, the infantrymen would climb over the bank and man the boats to launch the assault.

While the artillery fired on the banks of the Twente Canal with high explosive and smoke shells, the me n paddled like hell to reach the other side of the canal. Over the heads of the attackers, machine guns fired and pinned down the German soldiers in their concealed positions. A Bren machine gunner in the bow of the assault boats also fired at the German positions. The assault companies reached the bank in a couple of minutes. C-company lost 4 men during the crossing. After the men reached the other side, they jumped out of the boats and crawled up the steep canal dike. Dunlop led his men from the canal dike to several farms. This attracted heavy fire, that forced Dunlop to disperse his company. In front of him lay the forest edge, his first goal. It was 7:38.[18]

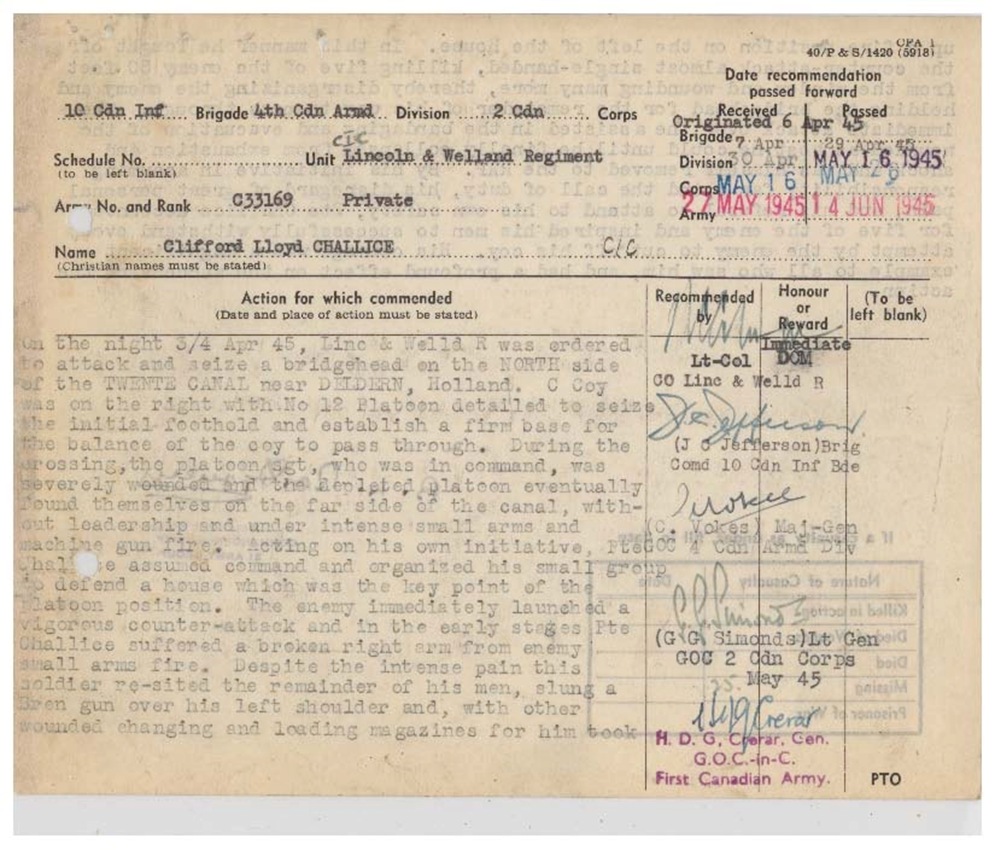

Meanwhile, on the right, Dunlop’s men were fighting for their lives: they were involved in fierce close-range firefights. Every platoon had taken possession of a farm, but the Germans had cut off every farmhouse from the rest of the company. Dunlop and his headquarters were located on a large farm in the middle. The platoon, led by Lance Sergeant J.M. "Johnny" Mc Eachern occupied the small farm of Erve Rannink on the righthand side of Dunlop. One of his Bren machine gunners, Private Clifford Challice saw a group of Germans from the Fallschirm-Panzer-Division 1. Hermann Göring, preparing for an attack on Dunlop’s position. Together with his loader, Challice ran, continually firing, towards the Germans, and this resulted in the attack being repulsed.

When Challice returned to the farm where his platoon was located, a German potato masher hand grenade exploded and broke his arm.[19] Despite excruciating pain, Challice, with the help of his mates fastened the Bren gun strap to the shoulder of his broken arm. That forced him to fire his Bren with one arm. From a window, he fired constantly with his machine gun on German soldiers, who carried out various attacks on the farmhouse. Whenever a magazine was empty, another wounded man from his platoon changed the magazine.[20] Other wounded soldiers reloaded the empty magazines for re-use. Challice later told about it:

"I was not brave, I was crazy. A soldier should never get angry, but I only fight when I’m angry".

Challice shot at everything moving around the farm. One of the German attacks was beaten off 50 metres distance away from the farmhouse, because of the accurate shooting of Challice and the others. The bullets shattered the frames of the windows, where Challice was standing, but he kept firing from behind the windows. Five German Fallschirmjäger were killed and some wounded by Challice. After the enemy had been driven out, the Canadians counted 25 dead and eight wounded Germans around the farm. Through this action, Challice saved his platoon and was awarded with the Distinguished Conduct Medal.

When Dunlop noticed that his platoons were pinned down under heavy fire, he called for artillery support. He ordered the artillery to fire directly on his positions. Most of his men were inside the farmhouses; the Germans, on the other hand, were in the open fields around the farms, so they were exposed to the artillery. If he would fail to take action, his men would die. A terrific barrage of artillery and mortars descended on Dunlop’s positions. Several shells exploded around the Challice farm positions until the roof was hit. Sergeant McEachem was outside when the shells hit the ground, and he was seriously injured. Screaming, he lay, 50 metres from the farm in agony, but Challice and the rest of his men would have died if they had attempted to save him. With all the NCOs wounded or dead, Challice organized the defence anew. In the meantime, he kept firing his Bren. Once the artillery stopped the barrage, the Canadians saw many dead Germans lying around the farm. "They were outside and inside the farmhouses", Dunlop explained later. "Blew the Germans all to rat shit"." Meanwhile, the Germans still tried to infiltrate Dunlop’s line, with snipers, among others.

In and around the farm of Rannink on the Brinkstraat in Delden heavy fighting took place, including Private Clifford Challice. Source: Joël Stoppels

A excerpt from the Honours and Awards Citation in which Clifford Lloyd Challice nominated for a DCM (Distinguished Conduct Medal) Source: National Defence and the Canadian Forces

Definitielijst

- Fallschirmjäger

- German paratroopers. Part of the Luftwaffe.

- machine gun

- Machine gun, an automatic heavy quick firearm.

- Regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

The attack on the Wiene lock

West of the Lincoln and Welland Regiment, the Lake Superior Regiment launched a direct attack on the Wiene lock. Meanwhile, the A-Company, commanded by Major R.A. Colquhoun 500 metres west of the lock, would cross the canal with assault boats to attack the Germans defending the lock from the flank. With the sudden appearance of a British artillery officer of the 8th Armoured Brigade, the attack was given support by two artillery regiments and four searchlights from the British XXX Corps. The searchlights would produce artificial moonlight so the soldiers could see during their advance. Lieutenant-colonel Faire promised to shell the woods behind the lock and the landing site to allow the Canadians to cross without heavy resistance.[22] The machine guns of the New Brunswick Rangers, the mortars of The Superiors, three Wasp Carriers with flamethrowers and a tank squadron of the Canadian Grenadier Guards would also shell the woods on the other side of the canal.

Soon, problems arose with the assault boats. These had to be transported across exposed fields and lifted over a steep canal embankment. This delayed the attack until 11:00 p.m. Once the attack with the boats was launched, things went fairly smoothly. Although the leading platoon was attacked by several Germans with Panzerfausten, only one man was killed in the process, Martin Hellsten. When the men in the boats reached the other side of the canal, they jumped out of the boats. They soon eliminated the German resistance with their machine guns. The other two platoons rushed to their starting positions and launched the attack on the lock. Despite the heavy German resistance with panzerfausten, they managed to capture the lock at the cost of one death and one wounded. Ten Germans were made prisoners. Ten Germans were made prisoners during this action.[23] A few minutes after the capture of the lock, the 8th Canadian Field Squadron started building an emergency bridge. As the nearly undamaged lock fell into the Canadian's hands, the engineers merely needed to place a bridge over the 1.9-metre passage, allowing the vehicles to pass.

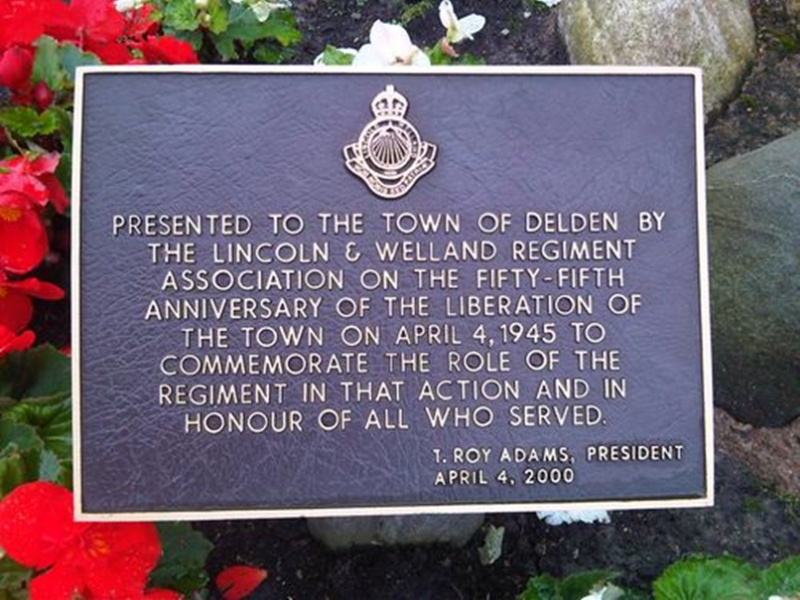

In the early morning of April 4, 1945, the Personnel Carriers and other vehicles of The Superiors drove north, where they met little opposition. Lieutenant Bruce Wright and his No. 13 platoon scouts were together with B- and C-company in the lead again and pursued the attack in the direction of Almelo. A patrol reported that the enemy had nearly all left Delden and on April 4 1945 at 07:00 PM, the town was liberated. In Delden, the Canadians were welcomed by very enthusiastic civilians and by the Mayor in his nightshirt. Thanks to the speed of the attack by the Superiors, many German positions were overrun. Advancing more than a third of the way from Delden to Almelo, Wright managed to prevent the blowing-up of a bridge by German Fallschirmjäger soldiers. During this action, they killed three Fallschirmjäger and took five prisoners, including the commanding officer.[24]

Tanks of the 4th Canadian Armoured Division drive through Delden. Source: Library and Archives Canada/ PA-131627

Definitielijst

- Brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- Fallschirmjäger

- German paratroopers. Part of the Luftwaffe.

- Regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- squadron

- A military unit in the Belgian navy usually six to eight small ships operating together under one command. The smallest military unit in the Dutch air force of about 350 men. In most countries is the designation of a military unit thesize of a company. It is either an independent unit, such as a battery, or part of a bigger Calvary unit. In the air force it is the designation of a unit of aircrafts.

Tank entry into Almelo via the railway line

During the Superior’s rapid attack, they captured an even larger bridge intact. Behind the Superiors followed the rest of the 4th Canadian Armoured, a large force of tanks, trucks, carriers and artillery. Around 1 p.m., the tanks of The British Columbia Dragoons carefully drove over the makeshift bridge of the lock over the Twente Canal near the destroyed Annabrink bridge in Delden. Engineers built a Bailey bridge series 40 that could handle more traffic than the bridge across the lock. After the bridge was ready for use at 4:00 p.m., the larger part of the 4th Canadian Armoured passed northwards across the bridge near the Wiene lock.[25] When the column reached Bornebroek, it turned out that Superior patrols had already penetrated the outskirts of Almelo. The still intact bridges were blown up at 1:00 p.m. and a wait for the arrival of bridge-building material was inevitable. However, Dutch civilians informed the Canadians that the railway bridge at de Riet station was still intact.

The tanks of the Grenadier Guards and armoured vehicles of the Recce, under the command of Lieutenant Robert Black of the Lake Superior Regiment, drove along the railway line into the town, where the enthusiasm of the population was boundless. Almelo, however, could not be completely taken without fighting. The resistance reported that the Vrieze bridge was intact, but the Germans were bound to defend it. Around 7:30 p.m., the Germans blew up the bridge. Next, one of the Stuart tanks got hit by a Panzerfaust, which took the lives of two of the crew members, Frank A. Williams and Milton R. Lewis.[26] On April 5, the northern section of Almelo was liberated. On the west side of Almelo, in the direction of Wierden, a fierce battle would ensue between the Canadians and fanatical Germans of the Fallschirm-Panzer Division 1, Hermann Göring

Definitielijst

- Panzerfaust

- German anti-tank gun used by the infantry. Consists of a long tube with the grenade mounted at the front side. It was a disposable weapon. After being used it cannot be reloaded. Major disadvantage is the long flame back blast from the tube.

- Regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Five-day battle for Wierden

From Almelo, on April 5, 1945, Vokes gave the order to continue the attack in the direction of the German Meppel, situated east of the Eems River. This advance proved to be one of the most successful armoured attacks, ever carried out by the brigade. The Germans pulled back in confusion and most targets were rapidly taken. Brigadier Jeffersons' 10th Infantry Brigade was deployed to secure the captured positions along the Twente Canal around Delden plus a section of the branch of the Twente Canal, that stretched from the Canal to the western part of Delden and Almelo. The Germans tried to regain control over the west side of the Twente Canal, to create an escape route for the German troops that were driven back by the 2nd and 3rd Canadian infantry divisions. Jefferson’ brigade felt it was fighting a private war, kilometres behind the 4th Armoured Division as it raced towards Germany.

For the 4th Brigade, it was a strange situation because the divisional HQ and the 10th Brigade were separated kilometres from each other. Radio contact was impossible. The mopping-up of German resistance was more difficult than expected, something the Algonquin Regiment discovered on the night of 5-6 April 1945 when they tried to capture Wierden, west of Almelo. Major George Cassidy decided to split his D-company into three assault groups, which would operate individually. One platoon was going to cross a branch of the Twente Canal near the Ten Bos factory in the vicinity of Almelo and would advance along the western bank. A second platoon would advance, parallel along the other side of the Aa brook. The company HQ and the 3rd platoon would simultaneously advance via road from Almelo to Wierden to an intersection at Wierden. When the two leading platoons had cleared the area to make the various access roads passable, they deployed a bulldozer, for the Germans had barricaded the access roads with tree trunks.

Due to the bad connections between the three groups, couriers had to be used. When these couriers informed Cassidy that the two leading platoons had reached the crossing place unnoticed and were digging in, he decided to attack with his group towards the road to the canal. The attack had hardly started when they came under heavy fire. Another courier reported that the two platoons had advanced north direction instead of west. That report however, came too late and they dug in at 800 metres.[27]

When the Algonquins had carried out a major mopping-up action around noon near Aadorp and had eliminated paratroopers of the 6. Fallschirmjäger-Division in the farms, a second crossing was carried out in broad daylight around 1:30 p.m. on April 6. The two platoons carried two assault boats and during the crossing of the Aa were met by heavy machine gun and mortar fire.[28] During this attack, the leading platoon lost 14 men, three-quarters of the complement. The next platoon lost three men. Lieutenant Robert Louis Richard was killed and the other platoon commander was injured. Afterwards, D-company secured a bridgehead across the canal near Wierden, but the operation was unsuccessful.

For the next three days, the Algonquins were involved in the fighting around Wierden, a strange engagement for the regiment. Even the employment of Typhoon aircraft could not break the German resistance. On April 9, 1945, a patrol succeeded in entering Wierden, where they did not find any more enemies: during the night the Germans had evacuated the village.[29] For almost a week the outer western edge of the municipality of Almelo had been on the front line. Within a couple of hours, the 10th Brigade raced further into Germany, behind the 4th Canadian Armoured Division. The battle for the Twente Canal was over.

On July 9, 1945, a plaque was unveiled to the memory of the Algonquin regiment, which liberated the village of Wierden after heavy fighting. Beside the monument are, from left to right, Major Robert Saville, Major L.C. Taylor. Source: Library and Archives Canada/ PA-131069

On September 12, 2009, the Dutch Association for the conservation of historic military vehicles ‘Keep Them Rolling’ unveiled a monument at the Wiene Locks. Source: Joël Stoppels.

Notes

- Bollen, H. & Vroemen, P., Canadezen in actie, Terra, pp. 95-113.

- Stacey,C.P., The Canadian Army 1939-1945: an official historical summary, Ottawa, 1984.

- Zuehlke, M., On to Victory: The Canadian Liberation of the Netherlands March 23 - May 5, 1945, Greystone Books,Canada 2010, pp. 29-41.

- Forrester, C., Monty's Functional Doctrine: Combined Arms Doctrine in British 21st Army Group in Northwest Europe, 1944-45, Wolverhampton Military Studies, 2015.

- Zuehlke, M., On to Victory: The Canadian Liberation of the Netherlands March 23 - May 5, 1945, Greystone Books ,Canada, 2010, pp. 153-54.

- South Alberta Regiment War Diary, April 1945, RG24, Library and Archives of Canada.

- Graves, D., South Albertas: A Canadian Regiment at War, Robin Brass studio, Toronto, 1998, pp. 305-06.

- Zuehlke, M., On to Victory: The Canadian Liberation of the Netherlands March 23 - May 5, 1945.

- Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders War Diary, April 1945, RG24, Library and Archives Canada.

- 10th Canadian Infantry Brigade War Diary, April 1945, RG24 Library and Archives Canada.

- Cassidy, G.L., Warpath: From Tilly-la-campagne to the Kusten Canal, Paperjacks, Markham, 1980, p. 335.

- Zuehlke, M., On to Victory: The Canadian Liberation of the Netherlands March 23 - May 5, 1945.

- Hans J.A.G. Pol, Onze vergeten bevrijders, Stichting Oald Hengel, pp. 60-66.

- Lake Superior Regiment (Motor) War Diary, April 1945, RG24, Library and Archives Canada.

- Mark Zuehlke, On to Victory: The Canadian Liberation of the Netherlands March 23 - May 5, 1945..

- Geoffrey Hayes, The Lincs: A History of the Lincoln and Welland Regiment at War, in: Maple Leaf Route, Alma, 1954, pp. 252-253.

- Lincoln and Welland Regiment War Diary, April 1945, RG24, Library and Archives Canada.

- Geoffrey Hayes, The Lincs: A History of the lincoln and Welland Regiment at War, in: Maple Leaf Route, Alma, 1954), pp. 113-114.

- Geoffrey Hayes, The Lincs, p. 114.

- "Canadian Army Overseas Honours and Awards Citation details", Directorate of Heritage and History, department of National Defence, www.cmp-cpm.forces.gc.ca/ (bezocht 10 november 2017).

- Geoffrey Hayes, The Lincs: A History of the Lincoln and Welland Regiment at War, in: Maple Leaf Route, Alma, 1954, pp. 114-116.

- 4th Canadian Armoured brigade War Diary

- Lake Superior Regiment War Diary.

- Lake Superior Regiment War Diary.

- 4th Canadian Armoured Brigade War Diary.

- C.B. Cornelissen, Almelo frontstad, de bevrijding van Twente, Boekwinkel Heinink, Denekamp, 2013.

- Cassidy, G.L., Warpath: From Tilly-la-campagne to the Kusten Canal, Paperjacks, Markham, 1980, p. 335.

- Algonquin Regiment War Diary, April 1945, RG24, Library and Archives Canada.

- G.L. Cassidy, Warpath , pp. 337-39.

Definitielijst

- brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- Fallschirmjäger

- German paratroopers. Part of the Luftwaffe.

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- machine gun

- Machine gun, an automatic heavy quick firearm.

- mortar

- Canon that is able to fire its grenades, in a very curved trajectory at short range.

- paratroopers

- Airborne Division. Military specialized in parachute landings.

- Regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Information

- Article by:

- Joël Stoppels

- Translated by:

- Cor Korpel

- Published on:

- 15-09-2024

- Last edit on:

- 30-09-2024

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Related books

Sources

- BOLLEN, H. & VROEMEN, P., Canadezen in actie, Terra - Lannoo.

- CASSIDY, G.L., WARPATH Canadians at War #3, Paperjacks, 1980.

- FORRESTER, C., Monty's Functional Doctrine, Helion And Company, 2015.

- GRAVES, D.E., South Albertas: A Canadian Regiment at War, Robin Brass Studio, 2004.

- ZUEHLKE, M., On to Victory, Greystone Books,, 2010.

- Thanks to Anne Palmer for her help in correcting the text.