Introduction

The Battle of the St. Lawrence was a lesser known yet critical chapter in the Second World War, where Canada faced direct enemy attacks on its home territory. It was a localized manifestation of the larger Battle of the Atlantic, with the primary objective of the German Kriegsmarine being the disruption of vital supply lines between Canada and its allies, primarily Great Britain and the Soviet Union. These supply lines were essential, as Canada had become a significant contributor to the war effort, supplying vast amounts of military equipment, materials, and resources.

Definitielijst

- Kriegsmarine

- Germa navy. Part of the Wehrmacht next to Heer and Luftwaffe.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

Background of Canada's Involvement in World War II

Canada’s entry into World War II was both a symbolic and strategic move. On September 10, 1939, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King declared war on Germany, a week after Britain, asserting Canada's newly independent status from the 1931 Westminster Treaty. Although initially reluctant to fully commit to the conflict, Mackenzie King recognized the growing necessity for Canadian involvement as the war progressed, particularly following the German invasion of France and the evacuation of Dunkirk in 1940. The Canadian government mobilized its industrial and military resources, with production levels soaring under the authority of the War Measures Act. From 1940 to 1945, Canada produced more than 815,729 military vehicles and other essential supplies, valued at over $3 billion, which were vital to the Allied war effort.

However, these supplies had to cross the Atlantic, and it quickly became apparent to German intelligence that Canada was playing a critical role in supporting Great Britain. This led to the development of a German strategy aimed at disrupting the flow of supplies, leading to the extension of the U-boat campaign into Canadian waters.

Definitielijst

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- strategy

- Art of warfare, the way in which war should be conducted in general.

- U-boat

- The German name for a submarine. German U-Boats (Submarines) played a very important role during the course of warfare until May 1943. Many cargo and passenger ships were torpedoed and sunk by these assassins of the sea.

The Beginning of the Battle of the St. Lawrence

The Battle of the St. Lawrence began in May 1942, marking the first time that World War II reached Canadian soil. On May 12, 1942, German U-boats entered the St. Lawrence River, sinking two merchant ships, s.s. Nicoya and s.s. Leto, within hours. These attacks sent shockwaves through Canada, as they were the first casualties of the war on Canadian territory. The unexpected nature of these assaults caught Canada off guard, as there had been little preparation for defending the St. Lawrence River from U-boat incursions.

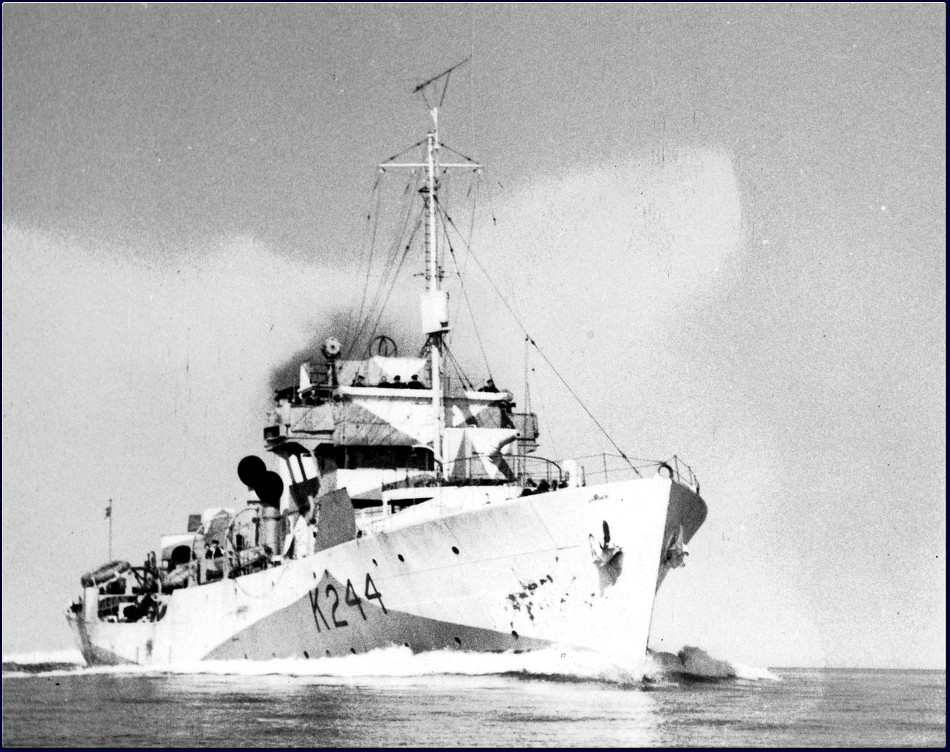

The German U-boat campaign was effective largely due to the vulnerability of Canadian merchant ships and the inadequacy of Canada’s early defense measures. The Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) and Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) were initially unprepared to protect the vast and strategically important waterway. The naval base in Gaspé, Quebec, NCMS Fort Ramsay, had limited resources, including just one small military ship and no aircraft, which proved insufficient to counter the U-boat threat.

Definitielijst

- U-boat

- The German name for a submarine. German U-Boats (Submarines) played a very important role during the course of warfare until May 1943. Many cargo and passenger ships were torpedoed and sunk by these assassins of the sea.

Escalation of the Conflict

Following the initial attacks, the Canadian government responded by sending additional ships and planes from Nova Scotia to patrol the St. Lawrence. By July 6, 1942, German U-boats had intensified their attacks, sinking three more ships in a single convoy, further alarming the Canadian public. The government was under increasing pressure to act, and soon, warships were strategically deployed throughout the river to protect and escort merchant ships.

The Fairy Battle of the ARC destroyed about twenty U-boats between 1942 and 1944. Source: Canada Aviation and Space Museum

Despite the increased protection, U-boats continued to penetrate the St. Lawrence River. On September 6 and 7, 1942, five more ships were sunk. The situation became so dire that on September 9, 1942, the federal government made the decision to close the St. Lawrence River to all overseas shipping. This decision forced the rerouting of Canadian war materials through the United States, adding time and logistical challenges to the war effort.

Definitielijst

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- strategy

- Art of warfare, the way in which war should be conducted in general.

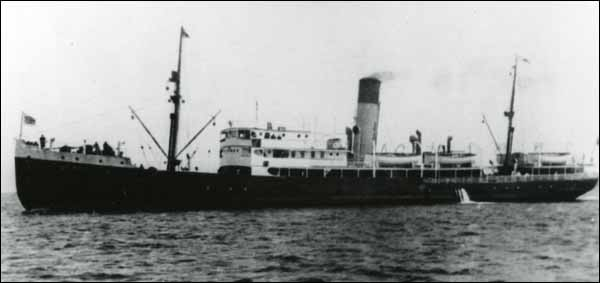

Civilians Caught in the Crossfire: The Tragedy of the SS Caribou

One of the most tragic incidents of the Battle of the St. Lawrence occurred on October 14, 1942, when the s.s. Caribou, a civilian ferry, was torpedoed by U 69 (1940) while traveling between Newfoundland and Nova Scotia. The ship was carrying 237 passengers, including women and children, along with military personnel. Despite being escorted by the NCSM Grandmère, the Caribou was sunk, resulting in the deaths of 136 passengers, including many civilians. This attack underscored the brutal nature of the war and brought the reality of the conflict home to Canadians in a way that no previous battle had.

The SS Caribou. Source: Queen Elizabeth II Library, Memorial University of Newfoundland via The Canadian Encyclopedia

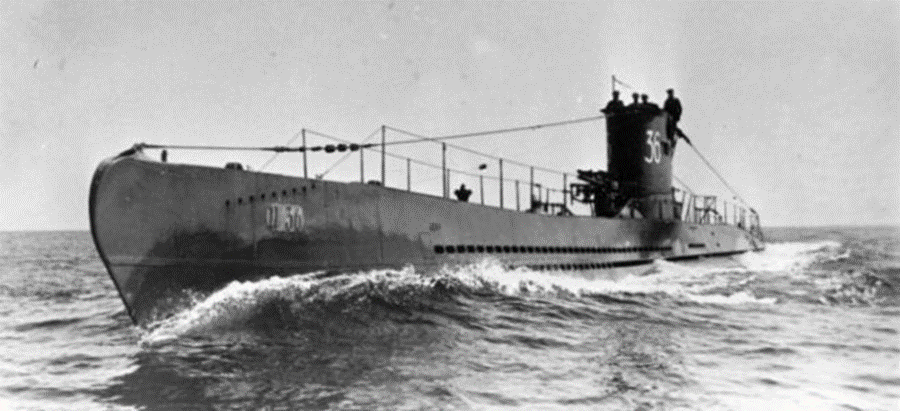

German Submarine Operations in 1943

While the intensity of U-boat attacks in Canadian waters decreased toward the end of 1942, isolated incidents continued. Notably, in November 1942, a German submarine off the coast of Chaleur Bay dropped off Werner Janowski, a German spy, who was apprehended shortly thereafter. U-boats also conducted rescue missions for prisoners, but these attempts largely failed. One of the more unusual operations involved the establishment of a weather station by German forces in Labrador, known as WFL-26, which provided weather data for U-boat operations. This weather station was not discovered until after the war.

The U-536, who tried to achieve a prisoner rescue mission in 1943. Source: Bundesarchiv, DVM 10 Bild-23-63-66 / Unknown / CC-BY-SA 3.0

Definitielijst

- U-boat

- The German name for a submarine. German U-Boats (Submarines) played a very important role during the course of warfare until May 1943. Many cargo and passenger ships were torpedoed and sunk by these assassins of the sea.

The Turning Tide: Reopening the St. Lawrence

By the end of 1943, the tide of the war had shifted in favor of the Allies. The impending D-Day invasion of Normandy required a significant increase in war materials, prompting the Canadian government to reopen the St. Lawrence River to overseas shipping. A stronger military presence and the successful decryption of German communications allowed Canada to protect the vital shipping lanes more effectively. U-boats were forced to remain submerged longer, limiting their ability to carry out attacks. As a result, only three ships were sunk in 1944, and no ships were lost in 1945.

Definitielijst

- D-Day

- The day of the long awaited invasion of western Europe in Normandy, France, 6 June 1944. After a long campaign of deception the allies attacked the coast of Normandy on five beaches to begin their march on Nazi Germany. Often explained as Decision Day, though this is entirely correct. The D stands for Day as generally used in military language. In this case it means an operation beginning on day D at hour H. Hence “Jour J“ in French.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

The Legacy of the Battle of the St. Lawrence

The Battle of the St. Lawrence had significant strategic and psychological implications for Canada. It marked the first time that Canada had been attacked on its own territory since the War of 1812, and it brought the realities of war to Canadian shores. In total, 23 Allied ships were sunk, resulting in more than 375 casualties. Despite these losses, over 2,200 ships successfully navigated the St. Lawrence River and completed their overseas missions, contributing significantly to the Allied war effort.

The battle demonstrated the critical importance of Canada’s role in supplying war materials to its allies and highlighted the challenges of defending such an extensive and vulnerable coastline. The response to the U-boat threat forced Canada to strengthen its naval and air defenses, lessons that would have lasting impacts on the country’s military capabilities in the post-war era.

In retrospect, the Battle of the St. Lawrence may not be as widely remembered as other theaters of World War II, but its significance cannot be understated. It was a battle fought on home soil, involving not only military personnel but also civilians, and it tested Canada’s resolve and ability to defend itself in a time of global conflict.

Definitielijst

- U-boat

- The German name for a submarine. German U-Boats (Submarines) played a very important role during the course of warfare until May 1943. Many cargo and passenger ships were torpedoed and sunk by these assassins of the sea.

Ships and casualties of the St-Lawrence battle

| Date | Sunken ship | Nationality | Casualties | Sunken by |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1942-05-12 | s.s. Leto | Netherlands | 12 | U 553 |

| 1942-05-12 | s.s. Nicoya | UK | 6 | U 553 |

| 1942-07-06 | s.s. Anastassios Pateras | Greece | 3 | U 132 |

| 1942-07-06 | s.s. Hainaut III | Belgium | 1 | U 132 |

| 1942-07-09 | s.s. Dinaric | UK | 4 | U 132 |

| 1942-07-20 | s.s. Frederika Lensen | UK | 4 | U 132 |

| 1942-08-27 | s.s. Chatham | USA | 14 | U 517 |

| 1942-08-28 | s.s. Arlyn | USA | 12 | U 517 |

| 1942-09-03 | s.s. Donald Stewart | Canada | 3 | U 517 |

| 1942-09-06 | s.s. Aeas | Greece | 2 | U 165 |

| 1942-09-07 | HMCS Racoon | Canada | 37 | U 165 |

| 1942-09-07 | s.s. Oakton | Canada | 3 | U 517 |

| 1942-09-07 | s.s. Mount Pindus | Greece | 2 | U 517 |

| 1942-09-07 | s.s. Mount Taygedus | Greece | 2 | U 517 |

| 1942-09-11 | HMCS Charlottetown | Canada | 9 | U 517 |

| 1942-09-15 | s.s. Saturnus | Netherlands | 1 | U 517 |

| 1942-09-15 | s.s. Inger Elisabeth | Norway | 3 | U 517 |

| 1942-09-16 | s.s. Joanis | Greece | Unknown | U 165 |

| 1942-10-09 | s.s. Carolus | Canada | 11 | U 69 |

| 1942-10-11 | s.s. Waterton | UK | Unknown | U 106 |

| 1942-10-14 | s.s. Caribou | UK | 136 | U 69 |

| 1942-10-14 | HMCS Magog | Canada | 3 | U 1223 |

| 1944-11-25 | HMCS Shawinigan (K 236) | Canada | 90 | U 1228 |

The HMCS Charlottetown, a Canadian military vessel patrolling in the St-Lawrence river who was sunk in 1942. Source: Canadian Naval Heritage website.

Information

- Article by:

- Jacob Benoit

- Published on:

- 05-10-2024

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Sources

- Veterans Affairs Canada

- the Canadian encyclopedia

- Histoire et sources-La bataille du Saint-Laurent dans son ensemble

- The Tragic Sinking of S.S. "Caribou"

- With thanks to the Naval Museum of Québec.