Two Native American veterans

This article, by Peter Bakker and Petra Sjouwerman, was originally published in 1995 under the title 'Two Indian veterans' in the magazine Indigo, which is now defunct. The original text has been adjusted in a number of places prior to publication on this website.

Canadian soldiers participating in the liberation of Europe and East Asia included several thousand First Nations people, of which about 150 were killed in action in Europe and the Far East. We met with two of the survisors in May 1995 when they visited the Netherlands to participate in the celebration of the country’s fifty years of liberation. Edward Commanda, an Ojibwe, and Archie Hodgson, a Slavey (a First Nations people in the Far North of Canada) but born in Western Canada. Both contributed as soldiers to the liberation of the Netherlands in 1945.

A 'still' from the video of the interview with Archie Hodgson. Source: Interview with Archie Hodgson (camera: Bart Drolenga and Saskia Rietmeijer; interviewer: Peter Bakker).

It is hard to imagine a greater contrast than between Archie Hodgson and Edward Commanda. Hodgson lives on the Nipissing First Nations Reserve near the village of Sturgeon Falls, Ontario. Commanda is also a First Nation but has never lived on a reservation. He hardly knows to which First Nations people he belongs.

For fifty years, Archie Hodgson kept under his mattress the address book in which the name was written of his sweetheart in the Netherlands. The love was mutual, but he couldn't bring her with him because he couldn't offer her a future in Canada. With shaking hands he opened the well-thumbed booklet in the presence of his host family. The name was still legible fifty years later. Miraculously, his new Dutch friends managed to track down relatives of his loved one the same day. Unfortunately, she had passed away two years earlier, but her sister and niece gave him a heart-warming welcome.

Consideration

And it wasn't just these two women who did this. Just prior to the big parade of all veterans in the city of Apeldoorn in 1995, Ben Haveman wrote an article in the nationwide Volkskrant newspaper about Archie Hodgson, including a photo. In the article, Hodgson talked about the discrimination against First Nations people (veterans or otherwise) in his village. For example, the local office of the Royal Canadian Legion, the official veterans association, had thwarted his membership. He had therefore come to the Netherlands on his own. Not in the official clothing of the Legion, but dressed in a coat of moose hide with colourful beadwork motifs, he walked in the parade for three hours, despite his 74 years. The handicrafts of the First Nations people was made especially for him. He did not walk in step, like the others did. Instead, he walked almost dancing with two women by his side. The people lining the road recognized him from the Volkskrant article and chanted his name: 'Archie! Archie!'. He was delighted with all the attention: articles in newspapers and even a TV performance for the Jeugdjournaal (Dutch TV educational news channel for children and pre-teens, similar to the BBC’s Newsround). "I had a fantastic time in the Netherlands throughout my stay. At home I am nobody, but here I am a hero!" When Archie talks about the difference between his experiences in the Netherlands and Canada, both he and the audience shed tears. At home he is given the cold shoulder because of his skin colour, but here no one finds that an objection. On the contrary, the Dutch treated him well. However, just like at home, his fellow Canadian veterans hardly have anything to do with him. The wife of one of them even told Archie's hostess not to get involved with that scum. But he himself is very flattered by the media attention. "Here they will know me by now. But those other veterans, they have been nothing more than faces in the crowd!"

Memories

Edward Commanda, a modest and silent man, is a member of the Royal Canadian Legion and wears the official clothing. Yet, against all regulations, he also wore an eagle’s feather atached to his beret. He received it from the reservation three years ago, the highest honour anyone can receive. He came to the Netherlands together with his First Nations wife, through official channels as part of a group of 150 veterans. The couple’s trip was funded by the reservation. Although they participate in the full program and visit war cemeteries and memorial ceremonies, they are a bit of outsiders. They are the only First Nations people in the group, except for one woman who is married to a First Nations veteran. He said: "I haven’t been in the Netherlands for long, and I can't remember exactly where I was then. I was a truck driver, tasked to transport ammunition to the frontlines and return with German prisoners of war. We were armed with sten guns, the German prisoners no longer resisted. We were not allowed to talk to them. We drove in columns with blackout lights, otherwise the Germans could spot and shoot us. We also had to avoid getting off the road, because then we could run into landmines." When his wife hears his stories, she says that it is new for her too. “He never talks about it, ever.”

We learn nothing about discrimination from Edward Commanda and his wife. He is now 69 years old and has been retired for a number of years. He used to be a milkman and then continued to work for a logging company for 25 years. During the veterans’ entrance into the city of Apeldoorn, he rode along in an old army jeep.

Underrepresented

Among the tens of thousands of veterans in Apeldoorn, First Nations veterans seemed underrepresented, while fifty years ago they were actually overrepresented. The six Mohawk veterans, who were a striking appearance with their feather headdresses five years ago at the previous major commemoration, are apparently not present at this occasion. Yet Commanda and Hodgson cannot be the only First Nations people. Archie can mention one by one the regiments that had many First Nations people in them: the Royal Winnipeg Rifles, the South Saskatchewan Regiment and the Calgary Highlanders. Why were there so few this time? Didn't they have money to come? Didn't they know about it? The two veterans have each seen only one other First Nations veteran. Commanda saw an Ojibwe who was initially not allowed to participate because he did not have an official badge from the organizers. And Archie had spoken to a First Nations veteran who no longer wanted to have anything to do with his ethnic background.

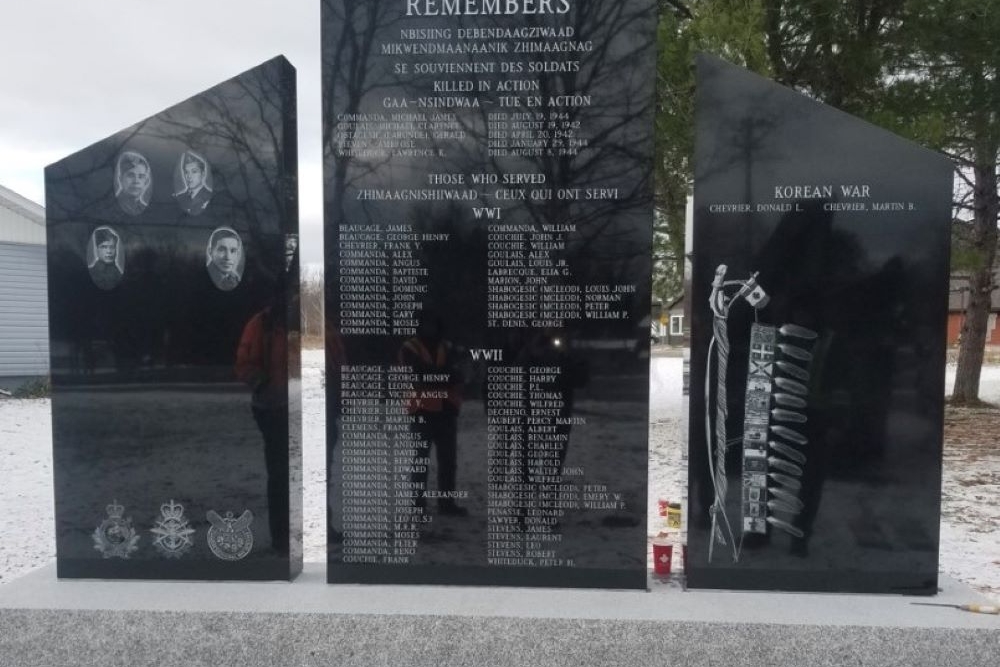

First Nations soldier memorial on the Nipissing First Nations reserve. Source: Nipissing First Nation, with permission of the copyright holder.

Family

Both Commanda and Hodgson also had family members in the military. Commanda's father had fought in the First World War [First World War/WW1: took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.] and an uncle had also been in Europe during the Second World War. His uncle was killed in the trial invasion of Dieppe and now lies buried in France. A brother and sister of Hodgson had also signed-up. His sister had served in Canada, whereas his younger brother returned from Europe crippled at the age of nineteen. "When we entered Brussels, he had a big hat on. Photos were taken of us, and I would like to have a photo of my brother. I don't have a photo of him."

Discrimination

Archie tells harrowing stories about the way he and many other First Nations people are treated in Canada. "Before the war I didn't actually suffer from discrimination. I have always lived near white people. It only started when I came back. I couldn't find a job at first, while White people found work quite easily. After a while I ended up in construction work. At present, the discrimination near my village is terrible. When I want to go to the hairdresser in my village, they deliberately cut it crookedly so that I won't return next time. Sometimes when I go shopping, I am only served after all the White people have been attended to. On my farm I have been harassed several times by villagers. One of my dogs has been poisoned and another has disappeared without a trace. Car repairs are done poorly, and I receive bills which are unreasonably high. I was only able to become a member of the Royal Canadian Legion when, just before I left for the Netherlands, I threatened to tell them how the fellow veterans were treating me. At that point, I received a letter full of apologies. But by then I didn’t want to become a member anymore." He has few friends among the Whites, and the nearest First Nations reservation is sixty miles away. His wife is a great support to him.

Pessimism

Edward Commanda brought with him a number of hand-outs containing an explanation about the medicine wheel (for the First Nations people, the medicine wheel serves as a compass that in a symbolic way guides a person through his walk of life here on earth, ed.) and other texts about the life philosophy of First Nations. "I got them from the tribal council. I'm giving them to people who’re interested in it." He mentions that he could not be a flag bearer at the last powwow (First Nations dance festival, ed.) in Toronto. That's traditionally a job for veterans, and they asked him to do it. "I'm glad I came to the Netherlands instead. I wouldn't have missed this for anything."

For Edward Commanda it is the first time that he is back in the Netherlands and he will not be able to afford a second time. Archie already has plans for when he returns to Canada. "When I return to Canada, I want to try to convince the local media to take an interest in the case. Then I can show them a stack of newspaper clippings from the Netherlands and maybe they will want to write something about the way a First Nations veteran is being treated in Alberta. But I fear nothing will change. The hatred of Fiurst Nations people is too deeply ingrained in the minds of the people."

Definitielijst

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- militarism

- Great influence of the army on civilian society.

- nationalism

- The pursuit of a people to become politically independence or securing such independence.

- Regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

- WW1

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

Information

- Article by:

- Peter Bakker

- Translated by:

- Simon van der Meulen

- Published on:

- 20-11-2024

- Feedback?

- Send it!