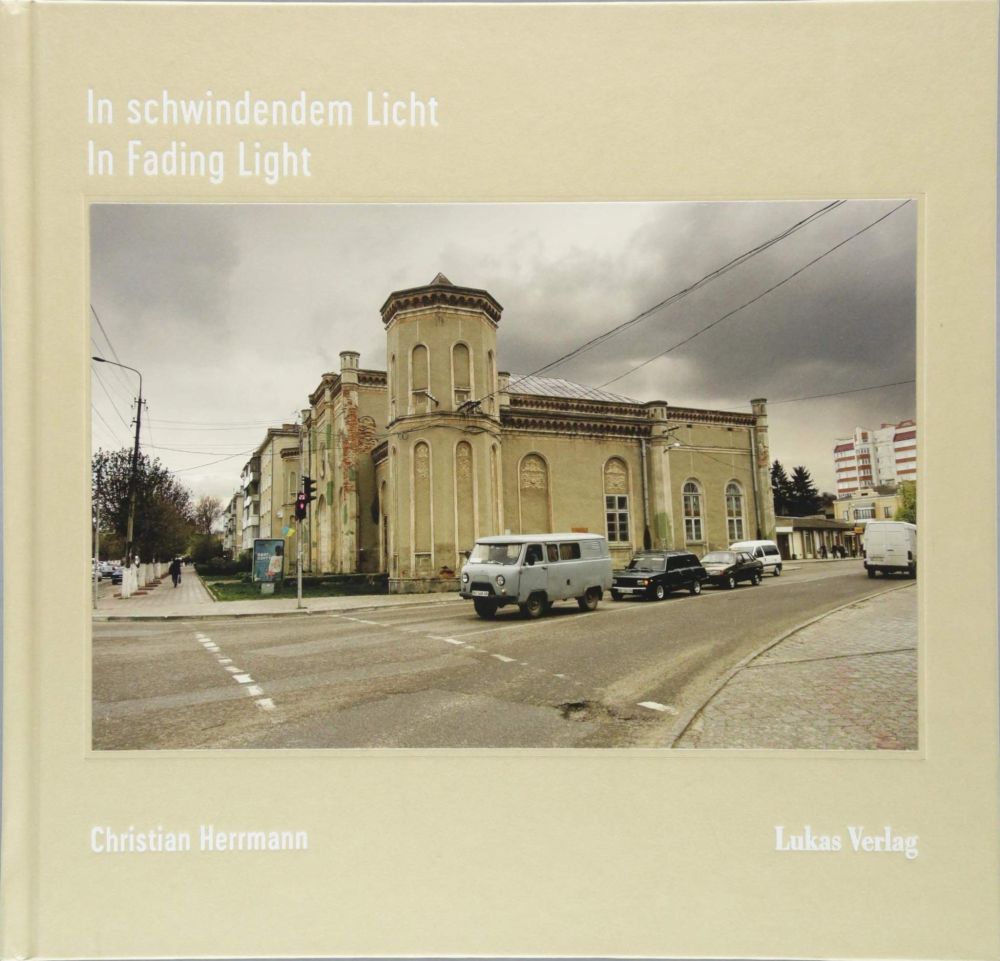

| Title: | In schwindendem Licht - In Fading Light |

| Writer: | Herrmann, C. |

| Published: | Lukas Verlag |

| Published in: | 2018 |

| Pages: | 180 |

| ISBN: | 9783867323017 |

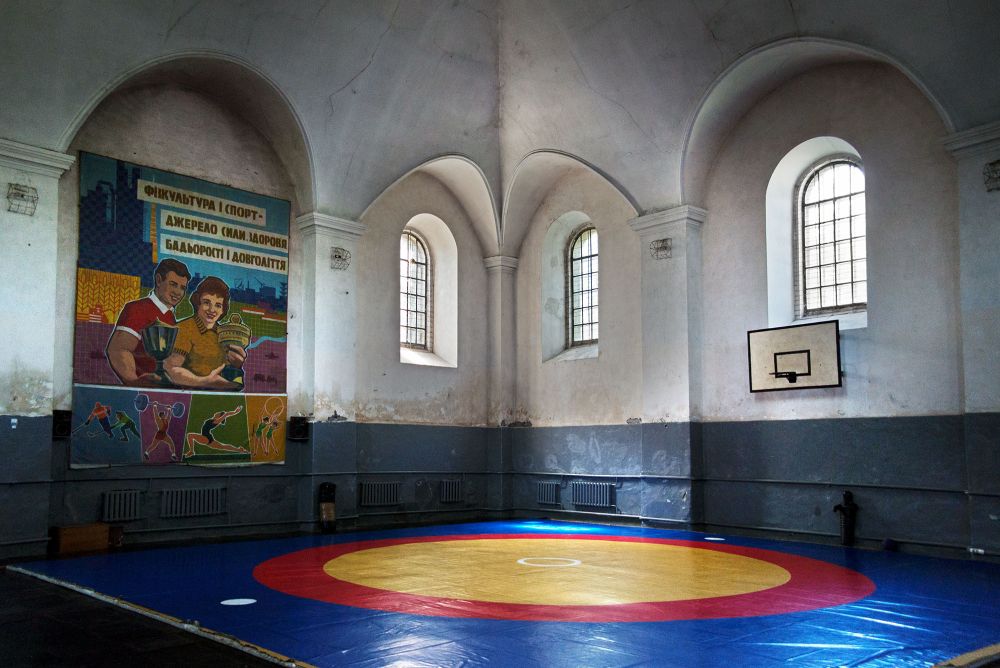

| Description: | The Cologne based German photographer and blogger Christian Herrmann has been traveling through Eastern Europe for some ten years in order to take pictures of lost Jewish communities. On his blog Vanished World a large part of his work can be seen but in addition, in 2018 the picture book ‘In schwindendem Licht - In Fading Light’ was published. It contains pictures of synagogues in ruins, neglected Jewish cemeteries and other buildings and sites of Jewish origin. Most of the Jews themselves aren't there anymore; murdered by the Nazis during WW 2 and the survivors have emigrated from the communist states to Israel, the United States and other countries where they felt safer than in their native countries. With them, a centuries old Jewish civilization was mostly lost. At the end of the twelfth and the beginning of the thirteenth century, the first Jewish communities were established in Eastern-Europe. They mostly consisted of merchants involved in trading between East and West. During the Middle Ages, many Jews would settle in Poland and the Ukraine as the conditions for settlement were favorable or having been expelled from elsewhere. For example, from 1492 and 1497 onwards, Jews were no longer allowed to live in Spain or Portugal respectively, unless they converted to Christianity. Jews settled in the East in rural areas in their own villages called sjetls or in towns where they lived in their own suburbs. This way, large Jewish communities were established in Warsaw, Krakow, Lublin, Lemberg, Minsk and Vilnius, all with their own culture. In the cities, Jews formed a significant minority with a marked influence on social and economic development. At the beginning of WW 2, over six million Jews were living in the East. For them, fate struck with the German invasion of Poland in September 1939 and the subsequent attack on the Soviet Union in 1941. Death squads of the German police and the SS triggered mass slaughter among the Jewish population and in addition hundreds of thousands of Jews were deported to the extermination camps in Poland. After the war, the survivors opted for emigration, rather than stay in the areas where the blood of their next-of-kin, friends and neighbors had been spilled. As a result of poverty, disinterest and anti-Semitism during the communist era, Jewish buildings and cemeteries were neglected or used for other, non-religious purposes. In his book, Christian Herrmann shows 110 pictures, made by himself, of Jewish heritage in fifty-seven towns and villages in the Ukraine, Moldavia, Poland, Hungary and Romania. Almost all pictures look somber and show decay, neglect and emptiness. One picture, taken on the location of the former sjetl Trochenbrod in the Ukraine, only shows a plot of land covered in snow and ice with power lines running over it. There is nothing to see anymore which reminds of its Jewish past. In other pictures, former synagogues can be recognized which are in a state of neglect or in use for non-religious purposes. For example, the former great synagogue in Sambir in the Ukraine is a fitness center nowadays and the former synagogue of Câmpulung in Romania was turned into a bar. On the site of the former Jewish cemetery in Berdytsjiv in the Ukraine stands an ancient carnival attraction and elsewhere in the country a similar location has been converted into a pitiful playground. Another saddening picture is of a decayed Jewish cemetery in Gura Humorului. A guard dog in its pen and empty cloth lines look shamefully misplaced on a site like this. More detailed pictures in the book also show the demise of Jewish civilization in the East. Some pictures for example show that Jewish tombstones have been used as building bricks or in the pavement of sidewalks. Other pictures show the legends of former Jewish stores. The traces of mezuzahs, photographed by Herrmann are very special. A mezuzah is a metal tube in which, according to traditional Jewish custom, a piece of parchment with on it a prayer from the Torah is kept. Mounting it on the jamb of a door is a sort of ritual initiation of the house. On entering, it is customary to touch the mezuzah in religious devotion and subsequently touch your lips. Looking at the pictures gives one the impression that many traces of the Jewish past are in danger of disappearing. Although many hopeful examples of restoration are being shown – financed with European money – many buildings are ready to be torn down while other thwart further development. 'These regions are no black boxes in which historical traces are being preserved forever,' historian Adam Kerpel-Fronius writes in his introduction. 'On the contrary, in these regions the landscape changes continuously, undergoing a period of intense modernization and change.' A good example of this is that door jambs with traces of mezuzahs disappear as soon as the owners have sufficient money to install a new door. This makes Christian Herrmann's work a race against time. In the beginning of his book the author indicates, quoting the German philosopher Walter Benjamin, his pictures do not need an explanation: "Ich habe nichts zu sagen. Nur zu zeigen' (I have nothing to say. Just to show). Beneath each picture are just the location, date and a very short description of what we see in both German and English. Unfortunately, more detailed information is missing so the less informed reader doesn't learn much about the history of what the picture shows. A more extensive explanation would have added much more. For the better informed reader, the pictures do have more expressive power and invite to search for further information. 'In schwindendem Licht - In Fading Light' contains intriguing, gripping pictures showing a neglected side of the Holocaust. Thinking of the extermination of the Jews, we mostly envisage the extermination camps but not the locations from which these victims have disappeared forever. 'While Auschwitz is a location of death, it is just as important to look after the locations where these victims once lived, ' the introduction reads. By documenting these places, we pay our respect to the victims. Adam Kerpel-Fronius writes: 'Christian Herrmann cannot bring back the dead but he does his best to conjure up their spirits'. At the same time, his work is a charge against the neglect and the unrespectful re-use of these locations. |

| Rating: |    Good Good |

Information

- Translated by:

- Arnold Palthe

- Article by:

- Kevin Prenger

- Published on:

- 07-03-2021

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Images

Horodenka, Galicia, 2015. Former Great Synagogue, now a gym hall. Bron: Christian Hermann.

Horodenka, Galicia, 2015. Former Great Synagogue, now a gym hall. Bron: Christian Hermann.

Pidhaitsi, Galicia, Ukraine, 2017. Trace of a mezuzah. Bron: Christian Hermann.

Pidhaitsi, Galicia, Ukraine, 2017. Trace of a mezuzah. Bron: Christian Hermann.

Karczew, Masovia, Poland, 2017. Jewish cemetery. Bron: Christian Hermann.

Karczew, Masovia, Poland, 2017. Jewish cemetery. Bron: Christian Hermann.

Related news

Searching for traces of lost Jewish life

The Cologne-based photographer and blogger Christian Herrmann has travelled Eastern Europe for years to document traces of Jewish life before the Holocaust. Here, in a belt between the Baltic and Black Seas, lived the majority of European Jews. During the Second World War, almost all of them were murdered by the German occupiers and their collaborators. What remains are traces of Jewish life: destroyed or misappropriated synagogues, overgrown cemeteries, tombstones in the street paving, and traces of home blessings on door jambs. His book In schwindendem Licht / In Fading Light presents 110 photos of Jewish heritage sites in 57 cities, towns and villages in Ukraine, the Republic of Moldova, Poland, Hungary and Romania. We’ve asked him some question about his photographs by e-mail.