The German Ostheer became bogged down in a war of attrition it could never win

Dr. Craig W.H. Luther is a retired U.S. Air Force historian (16 years at McClellan AFB, 11 years at Edwards AFB) and former Fullbrigh Scholar (Bonn, West Germany 1979-80). However, his primary passion has always been researching and writing about German military operations during WWII, and primarily on the eastern front. He has published seven books (and a half dozen articles) on this topic. We asked him some questions by e-mail about his research and his latest books.

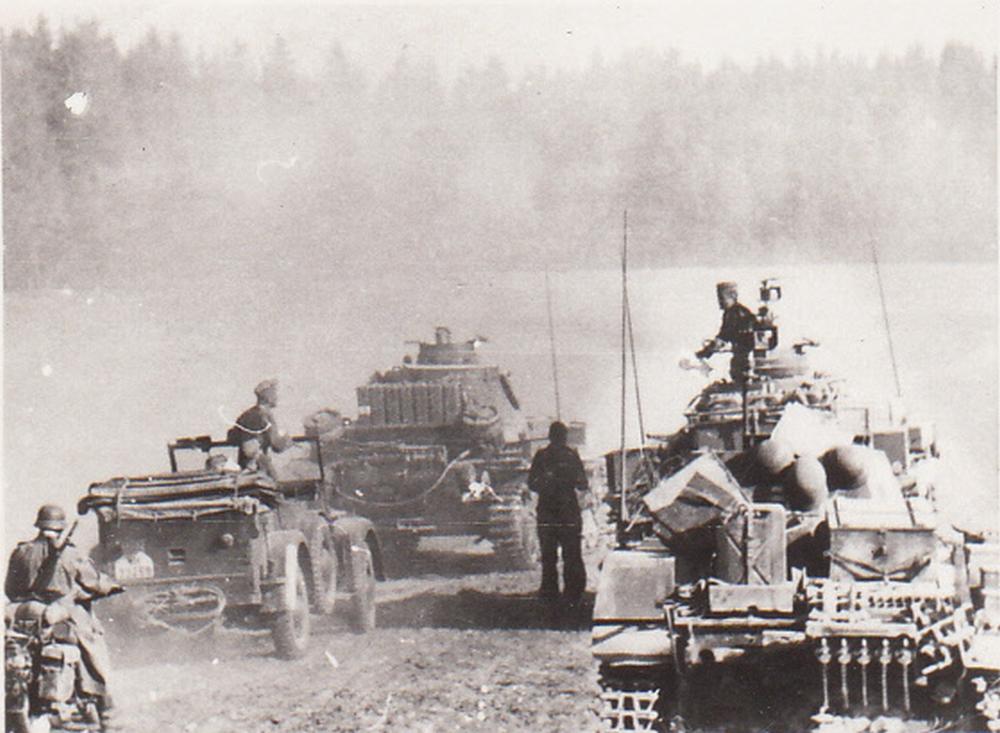

German soldiers during Operation Barborassa. Photo: U.S. National Archives

German soldiers during Operation Barborassa. Photo: U.S. National Archives

You’ve written several books about the Germans at the Eastern Front during World War 2. Could you tell us when and how this interest started? And what exactly makes this subject so interesting for you?

Like lots of young boys, I became interested in military things as a child. I recall purchasing all these tiny plastic tanks, guns, soldiers, etc., and having “battles” in my backyard. If I determined a tank had been “destroyed”, I loved nothing more than to blow it up with a fire cracker! As I grew older, of course, my interest gradually became a little more sophisticated, but just a little (I still find photos/videos of explosions totally intriguing!). More seriously, as a youngster I became fascinated with Nazi Germany (and WWII), because it seemed to symbolize the capacity we all have as human beings to do good and to do evil. War is the most extreme of all human endeavors, and it often brings out the best, and the worst, in human behavior.

Dr. Craig W.H. Luther. Your focus is strongly on the human side of war. Is that correct? Was this the same during the time you worked as U.S. Air Force historian?

Dr. Craig W.H. Luther. Your focus is strongly on the human side of war. Is that correct? Was this the same during the time you worked as U.S. Air Force historian?

Yes, you are indeed correct. In my books, I try to take the reader down into the trenches along side the soldiers — so he can almost see, feel, smell the reality of war. Of course, as an author, I can only go so far in approximating that reality. Indeed, as an author, my objective is to try to impose a certain (and, no doubt, artificial) order on the most chaotic and extreme of human experiences — organized human conflict. That duly noted, I always include dozens of first-person accounts in my books. For my “magnum opus”, Barbarossa Unleashed, I was able to interview, or correspond with, some 75 former German soldiers who had participated in the march on Moscow in the summer/fall of 1941. Sadly, these veterans are all gone now, so no one will ever again be able to conduct such interviews or correspondence.

As for the second part of your question, as an Air Force historian, I wrote extremely dry (and exceedingly dull!) institutional histories, which is why I retired early at age 60 — to write more of my own books.

In 2018 your book First Day on the Eastern Front was published. It covers the first 21 hours of Hitler's attack on Soviet Russia. What sources did you use and were you able to discover how the invasion was experienced by the German soldiers who carried out the operation? Did they support the operation and were they eager to participate in it?

I am quite proud of this book, because it is utterly unique — no one (at least no western historian) had hitherto attempted to research and write a full-length monograph on just the first day of Operation Barbarossa. (As an aside, the book won a nice little award from Stone & Stone WWII Books — a major aggregator/reviewer of such books — as one of the best six books published on WWII in 2018.) Again, I was able to use a large number of personal accounts, while also doing a “deep dive” into official German military records, for example the war diaries of the operations sections of army groups, armies, divisions, etc. For this book, thanks to a tip from the great David Glantz, I was able to engage one of the best Russian to English translators, Dr Richard Harrison, to translate a modest tranche of official Soviet records and personal accounts. So while the book is “weighted” toward the German side of things, it does include a fair amount of fascinating material illustrating the Red Army’s response to the German invasion. As for how the invasion was experienced by the German soldiers themselves, well, in many cases, it only took them a few hours to realize they were no longer fighting the French!

You edited and annotated the book Moscow Tram Stop, which was published in 2020. This book contains the front memoirs of a German doctor who was with the German spearhead in Russia. He must have experienced many horrors. Who was this doctor and how did he experience the war and how did he deal with all the suffering?

You edited and annotated the book Moscow Tram Stop, which was published in 2020. This book contains the front memoirs of a German doctor who was with the German spearhead in Russia. He must have experienced many horrors. Who was this doctor and how did he experience the war and how did he deal with all the suffering?

The memoirist is Dr Heinrich Haape, whose elite 18th Infantry Regiment marched well over a 1000 kilometers in summer/fall 1941, reaching a point beyond the town of Rzhev (220km W/NW of Moscow) by November. His memoir had not been republished in the English language since 1959 (it was first published by Collins in 1957). I edited and copiously annotated Haape’s memoir, adding color maps, new photographs/illustrations, and about a dozen appendices (including excerpts from several dozen of Dr Haape’s letters to his fiancee in Germany composed over the same time period covered in his memoir). Dr Haape was, without doubt, a very conservative, Protestant (Evangelisch) German (his father was a pastor), who supported Operation Barbarossa due to the “need” to rid Europe of the threat of Soviet Bolshevism; however, he was not a Nazi, and took no part in any criminal activities. Because even during the German advance on Moscow, the front, due to its ever-increasing length, was often porous, he often found himself in combat defending his battalion dressing station. As a result, by the end of 1942, he had become one of the most highly-decorated German doctors on the eastern front. I could go on and on about Dr Haape, but let me just say that his memoir is truly iconic and a “must read” for anyone interested in the German experience on the eastern front.

Soldiers of Barbarossa, which you wrote with co-author Dr. David Stahel, was also published in 2020. It’s about combat, genocide and everyday experiences on the Eastern Front from June till December 1941. It consists of excerpts from nearly 600 letters and diary entries of German soldiers during Operation Barbarossa. How did you obtain these personal documents and how did you select the experts out of the large amount of text? Is there a testimony that has impressed you the most?

First of all, let me note that working with Dr Stahel was a pleasure; we got along terrifically and assembled the book in only a year or so. However, we did take somewhat different approaches in our research. Simply put, most of my “raw material” for the volume came from the Library of Contemporary History in Stuttgart, which boasts one of the finest collections of letters and diaries of German soldiers in WWII (David gleaned most of his material from a repository of field post letters in Berlin). German soldiers sent billions of letters from the front to their loved ones during WWII, but sadly only an infinitesimal fraction has survived. Still, I believe the letters David and I assembled for this book provide a reasonably accurate picture of the German soldiers experiences during the first six months of the war on the eastern front. We made no attempt to “whitewash” their experiences — the letters reveal in graphic detail the good, the bad, and the (often very) ugly.

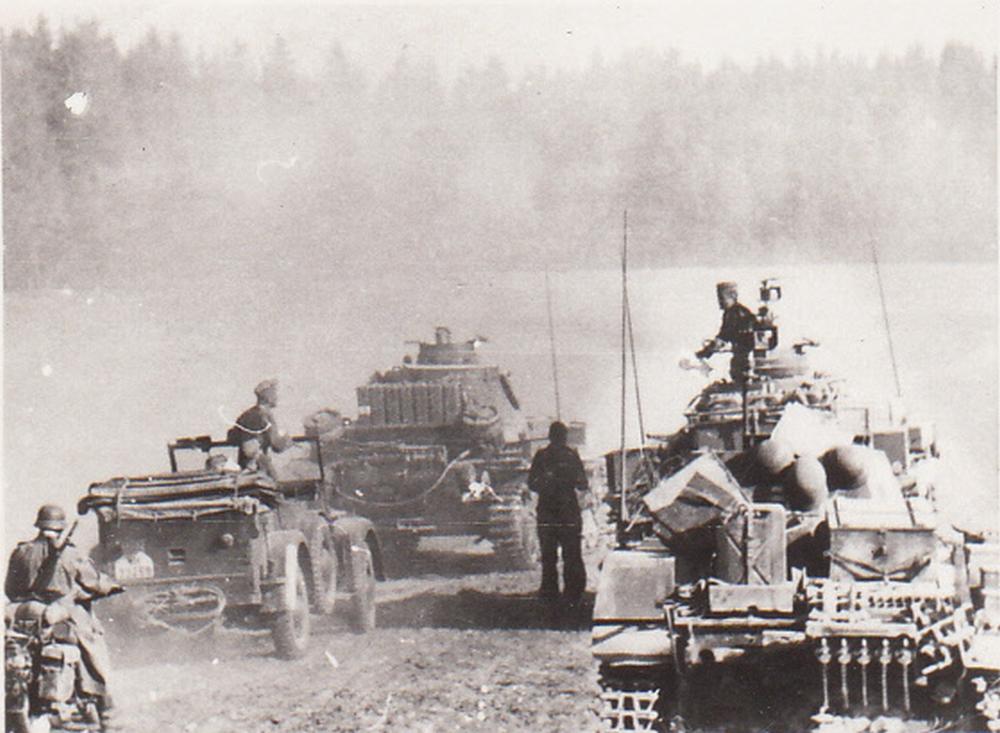

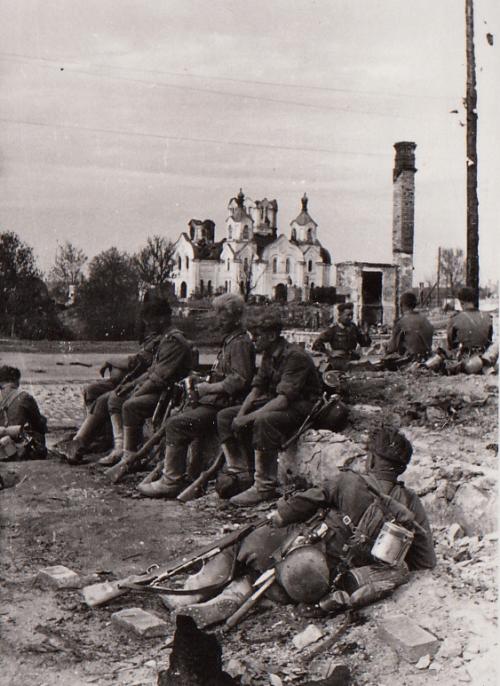

German troops somwhere near Minsk. Photo: U.S. National Archives

German troops somwhere near Minsk. Photo: U.S. National Archives

The reader will come away with real insight into the activities and the perspectives of the German Ostheer. Perhaps what is most noteworthy about those perspectives is how they slowly began to change as the weeks and months went by — how the soldiers’ largely collective conviction that the war would be swiftly brought to a victorious end gradually yielded to the stark realization that the “meat grinder” in the East was going to continue into the winter of 1941/42 and perhaps beyond. Note: I have been working with a great YouTube channel, Military1945.com, to produce short but graphic eastern front videos; these videos match rare footage to letters and diary entries from Soldiers of Barbarossa. To watch the videos, go to my WWII website and click on “Video Library.”

It is understandable that soldiers wrote about combat and about their daily lives, but in what ways does genocide appear in their texts? Did they write approvingly or disapprovingly about it? Is there much language influenced by Nazi propaganda? How actively involved was the common soldier in Nazi crimes at the Eastern Front?

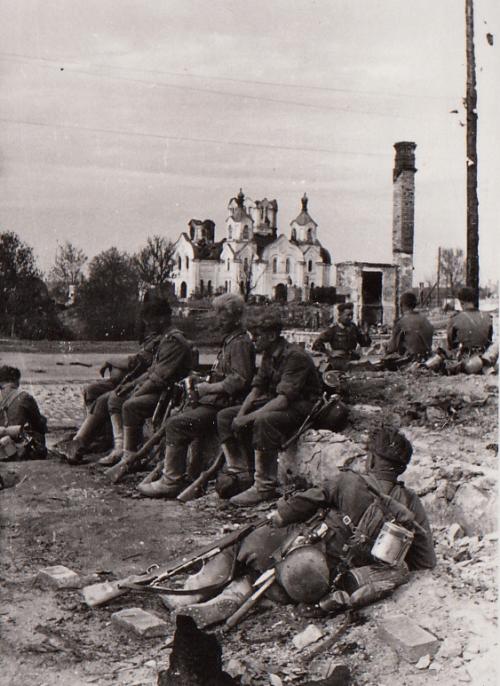

German soldiers take a rest. Photo: U.S. National ArchivesWow, it would take thousands of words to respond adequately to these queries, but I’ll give it a “shot”! In more than a few of the letters we find discussions of war crimes of various types. The Einsatzgruppen, or action squads of the SS, were active behind the front of the advancing Wehrmacht from the second day of the war. Regular German soldiers were often observers to the mass killing of Jews and others; many soldiers photographed these events and, of course, some wrote about them, while a small number even participated in the murderous actions. In some of the field post, the soldiers do indeed write approvingly about the killings; in others, they seem to be somewhat ambivalent about them (simply matter-of-factly explaining what they had witnessed). Indubitably, the National Socialist indoctrination to which they had been exposed since childhood played a major role in shaping their world view.

German soldiers take a rest. Photo: U.S. National ArchivesWow, it would take thousands of words to respond adequately to these queries, but I’ll give it a “shot”! In more than a few of the letters we find discussions of war crimes of various types. The Einsatzgruppen, or action squads of the SS, were active behind the front of the advancing Wehrmacht from the second day of the war. Regular German soldiers were often observers to the mass killing of Jews and others; many soldiers photographed these events and, of course, some wrote about them, while a small number even participated in the murderous actions. In some of the field post, the soldiers do indeed write approvingly about the killings; in others, they seem to be somewhat ambivalent about them (simply matter-of-factly explaining what they had witnessed). Indubitably, the National Socialist indoctrination to which they had been exposed since childhood played a major role in shaping their world view.

Conversely, one has to be quite careful when generalizing about human behavior: Many of the soldiers were not Nazis; some were stalwart Christians, repulsed by what they witnessed and experienced; others enthusiastically embraced the bloodshed as a way to rid Europe of “racially inferior” peoples. Still, my many years of research has led me to the conclusion that only a very small percentage of the German Landser (G.I.s) took part in such killing actions. Simply put, the Ostheer was perennially short of infantry, thus every man available was desperately needed along the line of contact (most of the genocidal actions of the Einsatzgruppen, SS Polizei battalions, and local militias, took place well behind the front).

Are there still important “gaps” in our historical knowledge and understanding of the events during those war years at the Eastern Front? Are there archives and other sources – maybe in Russia – that need to be better explored?

One of my greatest joys as a historian is that it’s like being on a perpetual Easter Egg hunt! Much to our collective surprise, shiny new “eggs” are always being discovered, giving historians ever more “grist for the mill”! My first major work (my doctoral dissertation) was a monograph on the 12th SS Panzer-Division “Hitler Youth”, and its role in the Normandy campaign of summer 1944. That book first appeared in 1987 (Blood and Honor, second, expanded edition, 2012). Virtually all of the divisional records, or so it was thought, had been destroyed by the time the remnants of the division withdrew back toward Germany to lick their wounds. Recently, however, at an archive in Prague, the war diary of the division’s 12th SS Panzer Regiment was located! As for the war on the eastern front, there are, no doubt, voluminous records inside former Soviet archives that have yet to be discovered or released (that said, the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation is now putting lots of WWII documents on the internet). During the period of “Glasnost” and following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Soviet archives became for a time more accessible to researchers. I’m not privy to the current situation, but I do believe it has become, once again, more difficult for an “outsider” to gain access to these archives (not to mention that a full-fledged war is going on in Europe at the moment!).

What is the most important thing you have learned yourself after spending so long researching German side on the Eastern Front?

Another tough question! Just focusing on the “German side”, what I would say is that, with 20-20 hindsight, it is clear that German preparations for Operation Barbarossa were plagued by overly-optimistic assumptions about just what was “doable” (that is a Blitzkrieg campaign ending in just 8-10 weeks!), and a failure to grasp the true nature, capabilities, and resources of the Red Army and the Soviet State. As the French diplomat and statesman Prince Talleyrand once said to Napoleon (in an effort to dissuade the Emperor from attacking Russia!): “Russia is never as strong as it looks, but never as weak as it seems.” While this ambivalence also tormented Hitler and his generals, in the final analysis they were convinced that “nothing was impossible for the German soldier!” And after pulverizing France and the British Expeditionary Force in just 42 days (after failing to defeat both nations in WWI), such hubris is, in a way, understandable.

German artillery. Photo: U.S. National Archives

German artillery. Photo: U.S. National Archives

More significantly, as the late English historian Paul Johnson opined, Barbarossa was simply “underpowered” — that is, there were not enough soldiers, artillery pieces, tanks, aircraft, etc., for the gargantuan task at hand. Moreover, to expand on my initial observation, every judgment made by the German General Staff prior to the start of the campaign — about operational planning, logistics, intelligence — was clouded by unjustified optimism. Despite the famous injunction of Prussian Field Marshal Helmuth von Moltke that “no war plan survives contact with the enemy”, German Barbarossa planners had no “Plan B” in case the Red Army and Soviet State withstood the initial invasion. In fact, all operations after the initial frontier victories (west of the Western Dvina-Dnepr river lines) and the Smolensk cauldron battle were essentially improvised. And the German Ostheer became bogged down in a war of attrition it could never win.

Is it possible to draw lessons from what happened on the Eastern Front during World War II for the current conflict in Ukraine?

Yes, I believe it is. In the first place, one is struck by how dramatically conventional warfare has changed since the 1940s. While the current Ukrainian battlefield — with AFVs, artillery, mortars, combat aircraft — may appear similar to a WWII battlefield, advances in technology have completely altered the face of modern warfare. Persistent satellite surveillance, precision weapons for both air and ground forces, advances in electronic warfare, unmanned aerial vehicles, and, last but by no means least, unprecedented use and numbers of mines, have collectively conspired to make 21st Century warfare uniquely different and deadly. In my view, it is not too much to posit that, in the first quarter of this century, we have again witnessed a real Revolution in Military Affairs (as also occurred in the period between World Wars I and II). And to draw a parallel to the eastern front in WWII, we are once again witnessing what, in effect, is an artillery-centric war of attrition that can only be won by the side with superior resources. From 1941/45 that side was the Soviet Union, today it is the Russian Federation.

Field graves of German soldiers. Photo: U.S. National Archives

Field graves of German soldiers. Photo: U.S. National Archives

Are you already working on a new book and is there anything else you want to say?

I published my short (45k words) Guderian manuscript (Guderian’s Panzers) with Strategy & Tactics Quarterly (Nr. 22) this past May. However, since Putin’s full-on invasion of Ukraine, I have dedicated most of my time to studying and discussing the current Russo-Ukraine War. I believe the most important thing I could say to conclude this “Q&A” is to urge folks — Americans & Europeans — to pay more attention to this dangerous and relentlessly escalating conflict. In my view, we are one serious blunder away from all-out war with Russia. It may also be that the U.S. and NATO — who are now fantasizing about Ukraine renewing its failed offensive in spring 2024 — are preparing for a much longer war, instead of looking for a way to end it that takes into account certain conditions on the ground that will not change, short of WWIII (Russia will never surrender the territory it has taken since February 2022). Sometimes I question the collective sanity of our leadership in the U.S. and NATO — to wit, how can they possibly think that Ukraine can continue to sustain this war into 2024 (and even beyond!) when they have largely depleted their stocks of weapons and munitions without which Ukraine cannot fight? These are times that try men’s souls.

Readers with more questions can contact me through my website.

German soldiers during Operation Barborassa. Photo: U.S. National Archives

German soldiers during Operation Barborassa. Photo: U.S. National ArchivesYou’ve written several books about the Germans at the Eastern Front during World War 2. Could you tell us when and how this interest started? And what exactly makes this subject so interesting for you?

Like lots of young boys, I became interested in military things as a child. I recall purchasing all these tiny plastic tanks, guns, soldiers, etc., and having “battles” in my backyard. If I determined a tank had been “destroyed”, I loved nothing more than to blow it up with a fire cracker! As I grew older, of course, my interest gradually became a little more sophisticated, but just a little (I still find photos/videos of explosions totally intriguing!). More seriously, as a youngster I became fascinated with Nazi Germany (and WWII), because it seemed to symbolize the capacity we all have as human beings to do good and to do evil. War is the most extreme of all human endeavors, and it often brings out the best, and the worst, in human behavior.

Dr. Craig W.H. Luther.

Dr. Craig W.H. Luther.Yes, you are indeed correct. In my books, I try to take the reader down into the trenches along side the soldiers — so he can almost see, feel, smell the reality of war. Of course, as an author, I can only go so far in approximating that reality. Indeed, as an author, my objective is to try to impose a certain (and, no doubt, artificial) order on the most chaotic and extreme of human experiences — organized human conflict. That duly noted, I always include dozens of first-person accounts in my books. For my “magnum opus”, Barbarossa Unleashed, I was able to interview, or correspond with, some 75 former German soldiers who had participated in the march on Moscow in the summer/fall of 1941. Sadly, these veterans are all gone now, so no one will ever again be able to conduct such interviews or correspondence.

As for the second part of your question, as an Air Force historian, I wrote extremely dry (and exceedingly dull!) institutional histories, which is why I retired early at age 60 — to write more of my own books.

In 2018 your book First Day on the Eastern Front was published. It covers the first 21 hours of Hitler's attack on Soviet Russia. What sources did you use and were you able to discover how the invasion was experienced by the German soldiers who carried out the operation? Did they support the operation and were they eager to participate in it?

I am quite proud of this book, because it is utterly unique — no one (at least no western historian) had hitherto attempted to research and write a full-length monograph on just the first day of Operation Barbarossa. (As an aside, the book won a nice little award from Stone & Stone WWII Books — a major aggregator/reviewer of such books — as one of the best six books published on WWII in 2018.) Again, I was able to use a large number of personal accounts, while also doing a “deep dive” into official German military records, for example the war diaries of the operations sections of army groups, armies, divisions, etc. For this book, thanks to a tip from the great David Glantz, I was able to engage one of the best Russian to English translators, Dr Richard Harrison, to translate a modest tranche of official Soviet records and personal accounts. So while the book is “weighted” toward the German side of things, it does include a fair amount of fascinating material illustrating the Red Army’s response to the German invasion. As for how the invasion was experienced by the German soldiers themselves, well, in many cases, it only took them a few hours to realize they were no longer fighting the French!

The memoirist is Dr Heinrich Haape, whose elite 18th Infantry Regiment marched well over a 1000 kilometers in summer/fall 1941, reaching a point beyond the town of Rzhev (220km W/NW of Moscow) by November. His memoir had not been republished in the English language since 1959 (it was first published by Collins in 1957). I edited and copiously annotated Haape’s memoir, adding color maps, new photographs/illustrations, and about a dozen appendices (including excerpts from several dozen of Dr Haape’s letters to his fiancee in Germany composed over the same time period covered in his memoir). Dr Haape was, without doubt, a very conservative, Protestant (Evangelisch) German (his father was a pastor), who supported Operation Barbarossa due to the “need” to rid Europe of the threat of Soviet Bolshevism; however, he was not a Nazi, and took no part in any criminal activities. Because even during the German advance on Moscow, the front, due to its ever-increasing length, was often porous, he often found himself in combat defending his battalion dressing station. As a result, by the end of 1942, he had become one of the most highly-decorated German doctors on the eastern front. I could go on and on about Dr Haape, but let me just say that his memoir is truly iconic and a “must read” for anyone interested in the German experience on the eastern front.

Soldiers of Barbarossa, which you wrote with co-author Dr. David Stahel, was also published in 2020. It’s about combat, genocide and everyday experiences on the Eastern Front from June till December 1941. It consists of excerpts from nearly 600 letters and diary entries of German soldiers during Operation Barbarossa. How did you obtain these personal documents and how did you select the experts out of the large amount of text? Is there a testimony that has impressed you the most?

First of all, let me note that working with Dr Stahel was a pleasure; we got along terrifically and assembled the book in only a year or so. However, we did take somewhat different approaches in our research. Simply put, most of my “raw material” for the volume came from the Library of Contemporary History in Stuttgart, which boasts one of the finest collections of letters and diaries of German soldiers in WWII (David gleaned most of his material from a repository of field post letters in Berlin). German soldiers sent billions of letters from the front to their loved ones during WWII, but sadly only an infinitesimal fraction has survived. Still, I believe the letters David and I assembled for this book provide a reasonably accurate picture of the German soldiers experiences during the first six months of the war on the eastern front. We made no attempt to “whitewash” their experiences — the letters reveal in graphic detail the good, the bad, and the (often very) ugly.

German troops somwhere near Minsk. Photo: U.S. National Archives

German troops somwhere near Minsk. Photo: U.S. National ArchivesThe reader will come away with real insight into the activities and the perspectives of the German Ostheer. Perhaps what is most noteworthy about those perspectives is how they slowly began to change as the weeks and months went by — how the soldiers’ largely collective conviction that the war would be swiftly brought to a victorious end gradually yielded to the stark realization that the “meat grinder” in the East was going to continue into the winter of 1941/42 and perhaps beyond. Note: I have been working with a great YouTube channel, Military1945.com, to produce short but graphic eastern front videos; these videos match rare footage to letters and diary entries from Soldiers of Barbarossa. To watch the videos, go to my WWII website and click on “Video Library.”

It is understandable that soldiers wrote about combat and about their daily lives, but in what ways does genocide appear in their texts? Did they write approvingly or disapprovingly about it? Is there much language influenced by Nazi propaganda? How actively involved was the common soldier in Nazi crimes at the Eastern Front?

German soldiers take a rest. Photo: U.S. National Archives

German soldiers take a rest. Photo: U.S. National ArchivesConversely, one has to be quite careful when generalizing about human behavior: Many of the soldiers were not Nazis; some were stalwart Christians, repulsed by what they witnessed and experienced; others enthusiastically embraced the bloodshed as a way to rid Europe of “racially inferior” peoples. Still, my many years of research has led me to the conclusion that only a very small percentage of the German Landser (G.I.s) took part in such killing actions. Simply put, the Ostheer was perennially short of infantry, thus every man available was desperately needed along the line of contact (most of the genocidal actions of the Einsatzgruppen, SS Polizei battalions, and local militias, took place well behind the front).

Are there still important “gaps” in our historical knowledge and understanding of the events during those war years at the Eastern Front? Are there archives and other sources – maybe in Russia – that need to be better explored?

One of my greatest joys as a historian is that it’s like being on a perpetual Easter Egg hunt! Much to our collective surprise, shiny new “eggs” are always being discovered, giving historians ever more “grist for the mill”! My first major work (my doctoral dissertation) was a monograph on the 12th SS Panzer-Division “Hitler Youth”, and its role in the Normandy campaign of summer 1944. That book first appeared in 1987 (Blood and Honor, second, expanded edition, 2012). Virtually all of the divisional records, or so it was thought, had been destroyed by the time the remnants of the division withdrew back toward Germany to lick their wounds. Recently, however, at an archive in Prague, the war diary of the division’s 12th SS Panzer Regiment was located! As for the war on the eastern front, there are, no doubt, voluminous records inside former Soviet archives that have yet to be discovered or released (that said, the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation is now putting lots of WWII documents on the internet). During the period of “Glasnost” and following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Soviet archives became for a time more accessible to researchers. I’m not privy to the current situation, but I do believe it has become, once again, more difficult for an “outsider” to gain access to these archives (not to mention that a full-fledged war is going on in Europe at the moment!).

What is the most important thing you have learned yourself after spending so long researching German side on the Eastern Front?

Another tough question! Just focusing on the “German side”, what I would say is that, with 20-20 hindsight, it is clear that German preparations for Operation Barbarossa were plagued by overly-optimistic assumptions about just what was “doable” (that is a Blitzkrieg campaign ending in just 8-10 weeks!), and a failure to grasp the true nature, capabilities, and resources of the Red Army and the Soviet State. As the French diplomat and statesman Prince Talleyrand once said to Napoleon (in an effort to dissuade the Emperor from attacking Russia!): “Russia is never as strong as it looks, but never as weak as it seems.” While this ambivalence also tormented Hitler and his generals, in the final analysis they were convinced that “nothing was impossible for the German soldier!” And after pulverizing France and the British Expeditionary Force in just 42 days (after failing to defeat both nations in WWI), such hubris is, in a way, understandable.

German artillery. Photo: U.S. National Archives

German artillery. Photo: U.S. National ArchivesMore significantly, as the late English historian Paul Johnson opined, Barbarossa was simply “underpowered” — that is, there were not enough soldiers, artillery pieces, tanks, aircraft, etc., for the gargantuan task at hand. Moreover, to expand on my initial observation, every judgment made by the German General Staff prior to the start of the campaign — about operational planning, logistics, intelligence — was clouded by unjustified optimism. Despite the famous injunction of Prussian Field Marshal Helmuth von Moltke that “no war plan survives contact with the enemy”, German Barbarossa planners had no “Plan B” in case the Red Army and Soviet State withstood the initial invasion. In fact, all operations after the initial frontier victories (west of the Western Dvina-Dnepr river lines) and the Smolensk cauldron battle were essentially improvised. And the German Ostheer became bogged down in a war of attrition it could never win.

Is it possible to draw lessons from what happened on the Eastern Front during World War II for the current conflict in Ukraine?

Yes, I believe it is. In the first place, one is struck by how dramatically conventional warfare has changed since the 1940s. While the current Ukrainian battlefield — with AFVs, artillery, mortars, combat aircraft — may appear similar to a WWII battlefield, advances in technology have completely altered the face of modern warfare. Persistent satellite surveillance, precision weapons for both air and ground forces, advances in electronic warfare, unmanned aerial vehicles, and, last but by no means least, unprecedented use and numbers of mines, have collectively conspired to make 21st Century warfare uniquely different and deadly. In my view, it is not too much to posit that, in the first quarter of this century, we have again witnessed a real Revolution in Military Affairs (as also occurred in the period between World Wars I and II). And to draw a parallel to the eastern front in WWII, we are once again witnessing what, in effect, is an artillery-centric war of attrition that can only be won by the side with superior resources. From 1941/45 that side was the Soviet Union, today it is the Russian Federation.

Field graves of German soldiers. Photo: U.S. National Archives

Field graves of German soldiers. Photo: U.S. National ArchivesAre you already working on a new book and is there anything else you want to say?

I published my short (45k words) Guderian manuscript (Guderian’s Panzers) with Strategy & Tactics Quarterly (Nr. 22) this past May. However, since Putin’s full-on invasion of Ukraine, I have dedicated most of my time to studying and discussing the current Russo-Ukraine War. I believe the most important thing I could say to conclude this “Q&A” is to urge folks — Americans & Europeans — to pay more attention to this dangerous and relentlessly escalating conflict. In my view, we are one serious blunder away from all-out war with Russia. It may also be that the U.S. and NATO — who are now fantasizing about Ukraine renewing its failed offensive in spring 2024 — are preparing for a much longer war, instead of looking for a way to end it that takes into account certain conditions on the ground that will not change, short of WWIII (Russia will never surrender the territory it has taken since February 2022). Sometimes I question the collective sanity of our leadership in the U.S. and NATO — to wit, how can they possibly think that Ukraine can continue to sustain this war into 2024 (and even beyond!) when they have largely depleted their stocks of weapons and munitions without which Ukraine cannot fight? These are times that try men’s souls.

Readers with more questions can contact me through my website.

Used source(s)

- Source: Dr. Craig W.H. Luther / TracesOfWar

- Published on: 17-09-2023 15:34:50

Related news

- 11-'24: Postal artifacts provide a vibrant testament to the experiences of the Dutch people during WWII

- 10-'24: DigitalBattlefieldTours unlocks military tactics to a wide audience

- 08-'24: Researching his father’s WWII history became a passion for Steve Snyder

- 08-'24: Who was the owner of the photo album from Dachau?

- 07-'24: The British people welcomed African American servicemen with open arms

Latest news

- 03-03: A WWII helmet returns home 80 years after having been lost at Remagen Bridge, Germany

- 16-02: Armin T. Wegner and his letter to Hitler

- 14-02: The hugely popular ‘Standing with Giants’ installation returns to the British Normandy Memorial

- 27-01: Russia focuses on Soviet victims of WW2 as officials not invited to Auschwitz ceremony

- 27-01: Oswald Kaduk, ‘Papa Kaduk’ or a monster??

- 12-'24: Christmas and New Year message from our volunteers

- 11-'24: New book: Righteous Behind Barbed Wire

- 11-'24: Postal artifacts provide a vibrant testament to the experiences of the Dutch people during WWII

- 10-'24: DigitalBattlefieldTours unlocks military tactics to a wide audience

- 10-'24: Lily Ebert, Holocaust Survivor, Author and TikTok Star, Dies at 100