The British people welcomed African American servicemen with open arms

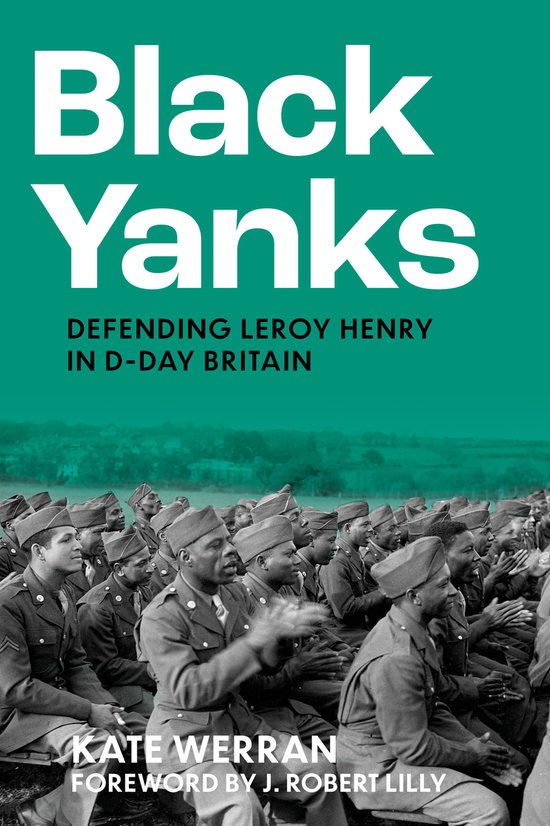

‘Black Yanks’, written by Kate Werran, is the story of how Leroy Henry, an African American soldier from Missouri, ended up on death row in D-Day Britain – and the extraordinary campaign that set him free. It unravels one of the earliest successes of the British Civil Rights Movement and re-examines the UK and USA's 'special relationship' in the build up to D-Day, 6 June 1944. Kate Werran unearths archival material to reveal the story behind the first significant – if uncelebrated – win in the civil rights movement. We asked her some questions by e-mail about her book that was published April 2024.

Segregated US troops at Bodmin Camp, Cornwall 1944. Courtesy of Kresen Kernow, E8681 George Ellis Collection

Segregated US troops at Bodmin Camp, Cornwall 1944. Courtesy of Kresen Kernow, E8681 George Ellis Collection

When did you first hear of Leroy Henry and what made you decide to write a book about him?

I first heard about Leroy Henry when researching my first book into the mutiny of an African American ordinance unit based in my Dad’s home town in Cornwall in 1943 (An American Uprising in Second World War England: Mutiny in the Duchy, Pen & Sword 2020). Leroy Henry was mentioned in Graham Smith’s book When Jim Crow met John Bull and has been the subject of a couple of academic papers by Professor Mary Louise Roberts and a few features online. But there’s never been a full examination of the story – including the context of what else was going on in the UK and testimony from local people who signed the petition and campaigned for Leroy Henry. By the time American Uprising was published, it just so happened that my family and I had moved back to Bath – and it seemed crazy for me not to look into the story a bit more carefully and talk to those who remembered it while there was still time.

In which army unit did Leroy Henry serve and have you been able to extract his personal background?

Corporal Leroy Henry (Technician Fifth Grade) served in the 3914th Quartermaster Gasoline Supply Company while he was in the UK. Although born in Des Arc, Arkansas, he was living in Missouri in 1940 and working as a labourer, according to the census. He named his aunt as closest living relative on his enlistment card. By the time he moved overseas to the UK he was married and employed as a truck driver with the QM company he served.

4. Knook Camp near Warminster in Wiltshire where Leroy Henry was court-martialled in May 1944. Photo: Kate Werran

4. Knook Camp near Warminster in Wiltshire where Leroy Henry was court-martialled in May 1944. Photo: Kate Werran

Leroy Henry was one of many African-American servicemen who were stationed in the United Kingdom in the prelude to D-Day, 6 June 1944. In their homeland they were discriminated against, but how were they treated by the British population?

The British people welcomed African American servicemen with open arms, much to the disgust of some white GIs. Although Britain then had an empire including many millions of people of colour, the Black British population was very small – maybe 15,000 which was based mostly in the port cities of London, Bristol and Cardiff. Obviously there was racism in Britain at that time and this was definitely more the case with upper rather than lower classes, but when segregation and its inherent racism came over in American troopships during the time Britain was ‘occupied territory’ (according to George Orwell) — it sparked a vigorous reaction. The US Army’s segregation (which mimicked the ‘Jim Crow’ separation of society in the American South) quite simply offended everyday people. The archives are full of criticisms and questions as to why African Americans should be treated any differently to the Polish, Czech and French people living in Britain and preparing for D-Day. British people resisted segregation and refused to allow it in dance halls, pubs and buses and trains. And there is mountains of evidence in newspapers, diaries, government morale reports and soldiers’ letters home to America that when violence spilled over on British soil, the Brits backed the African Americans, from a ‘fairness’ point of view more than anything else. It just didn’t wasn’t cricket to treat them any other way.

What and by whom was Leroy Henry accused and was he given a fair trial?

Execution shed at Shepton Mallet Prison that was revamped when the US Army took it over in 1942. Photo: Kate WerranLeroy Henry was accused by a Bath woman of rape in the early hours of 6 May 1944 – and within 24 hours had been arrested, interrogated, charged with rape and transferred to the guardhouse of Shepton Mallet Prison, which had been taken over by the US Army and was now 2912th Disciplinary Training Center – instantly recognisable to war film aficionados as the recruiting ground for the 1967 film The Dirty Dozen.

Execution shed at Shepton Mallet Prison that was revamped when the US Army took it over in 1942. Photo: Kate WerranLeroy Henry was accused by a Bath woman of rape in the early hours of 6 May 1944 – and within 24 hours had been arrested, interrogated, charged with rape and transferred to the guardhouse of Shepton Mallet Prison, which had been taken over by the US Army and was now 2912th Disciplinary Training Center – instantly recognisable to war film aficionados as the recruiting ground for the 1967 film The Dirty Dozen.

The United States of America (Visiting Forces Act) 1942 ensured that any crime committed by an American citizen in the UK during WW2 was to be dealt with by US military justice rather than British law. So three weeks later, Leroy Henry was moved to Knook Camp in Wiltshire for his US Army court martial. The prosecution’s case hinged on Henry’s confession to raping a stranger at knife point. But there were gaping holes in the argument. The victim could not identify his face, there was no evidence of rape on either the victim or Henry, no knife was ever found despite two inch-by-inch searches of the scene and the victims and husbands’ alibis for their whereabouts at various points did not tally. Leroy Henry’s defence maintained that his confession had been made under duress – he had not slept or been offered anything to eat or drink; he had fainted and been hit and the statement he signed was written by his interrogators. Not only did Leroy Henry not know what he signed his name to, it is uncertain he actually knew the meaning of the word ‘rape’. He argued that this was his third meeting with the woman. Each previous occasion he had paid her money for sex that had been pre-arranged earlier in the evenings, but this time she had been startled by the sudden appearance of her husband on the scene. Despite all this, the army panel found Leroy Henry guilty and sentenced him to death.

How did the British public and press react to the persecution of Leroy Henry?

After Leroy Henry had been given the death sentence there was a brief hiatus until news of the sentence reached local papers three days later. When it did, the reaction was immediate. 200 of the victim’s immediate neighbours and those who lived around the village common (where the assault is alleged to have taken place) signed a petition protesting Leroy Henry’s treatment. They said no screams or untoward sounds were heard on the village common on the night in question. Jack Allen, who owned a transport café in Bath, was outraged and along with his great friend Sam Day, an alderman, established a petition to demand clemency for the African American soldier. There was a general sense of anger that Henry had been sentenced to death for rape in Britain when it wasn’t a capital offence here in 1944 – nor had it been for more than 100 years. It underlined the fact that an alien law was at work. Claiming the issue would unite every class in Bath, they gave themselves eight days to show the strength of feeling. People went door-to-door collecting signatures, petition points sprang up all over the city. Those who still remember the furore say that things simply ‘snowballed’. The Daily Mirror meanwhile — then the most popular and best-read tabloid with a readership of millions — championed Leroy Henry’s case in a news report and then (four days before D-Day) with an impassioned editorial leader begging for clemency. By D-Day itself more than 18,000 had signed the petition. Letters were sent to General Eisenhower, the US Ambassador, the Home Secretary and various members of parliament. Other national and local newspapers picked up the story. Thurgood Marshall of the NAACP demanded a stay of execution, followed by its British equivalent; The League of Coloured Peoples (LCP). Resistance to Leroy Henry’s plight was at once rooted both in Bath (and its surrounding towns and villages) – and the nation. By D-Day +1 another 12,000 names had been added and by 12pm on 8 June 1944 the closing number was 33,132.

What role does the issue of Leroy Henry play in the history of the civil rights movement?

At least two American academics believe this episode changed America. Professor Mary Louise Roberts cites it as one of the 25 moments that defined/changed America – the precise point when ‘Jim Crow’ treatment became publicly unacceptable to the world. Professor J Robert Lilly defines this as when the US Army realised the narrative needed to change. Incidents like Leroy Henry’s case and other armed confrontations such as the mutiny of African American servicemen in Launceston, Cornwall and the lethal shoot-out in Bamber Bridge, caused the NAACP’s Walter White to come to Britain to investigate. White repeatedly lobbied for the US Army to be integrated – which was surely a pre-requisite for the integration of American society in the southern states. How could Southern society’s separation end while a segregated army still survived?

African American minesweepers in the UK. Courtesy of the National Archives of America, photo no 111-SC-181889

African American minesweepers in the UK. Courtesy of the National Archives of America, photo no 111-SC-181889

What happened to Leroy Henry after the Second World War?

Henry was promoted to sergeant and honourably discharged in 1946. He died in 1971 with no dependants and his occupation was listed as a cobbler. He is buried at the National Cemetery at Jefferson Barracks, Missouri.

What can today's readers learn from the injustice done to Leroy Henry and other ‘black yanks’?

Certain British TV commissioning editors feel cases like Leroy Henry’s prove Winston Churchill was the architect of a ‘secret apartheid state’ in the Second World War and there is at least one documentary in the pipeline with this thesis. I think this misses the point; it masks its true historical significance and traduces the efforts of those who fought so hard for the ‘Black Yanks’ they came to champion.

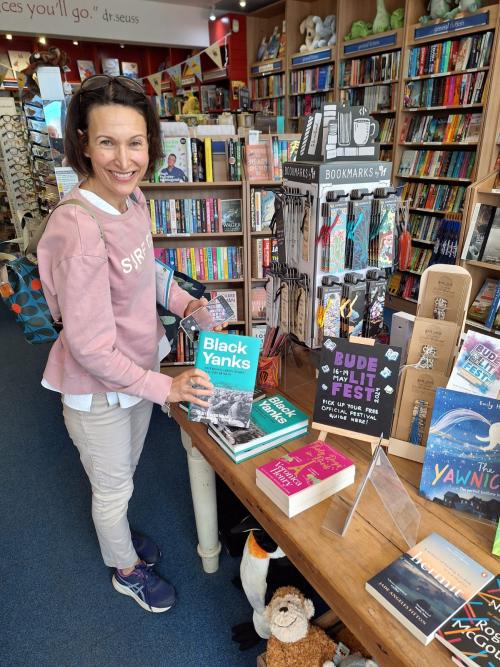

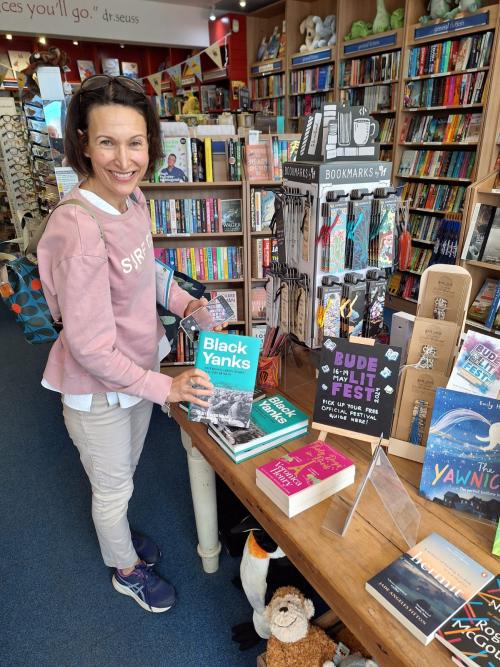

Kate Werran at Bude Literary Festival in May 2024. Photo: David WerranInstead, readers should see reactions to miscarriages of justice against African American servicemen such as Leroy Henry as catalysts in the civil rights struggle; moments that made the US rethink its policy on segregation and race. In the US Army’s own account of its history, the British response to the ‘Negro problem’ was ‘unique’ because the ‘usual friction’ was exacerbated by a ‘lack of racial discrimination by the British people’. Would any other population have reacted to the death sentence in the same way – making the US Army rethink Leroy Henry’s sentence? And ultimately segregation? I think cases like Leroy Henry’s show British society in a remarkably ‘modern’ light which is perhaps less familiar to us eighty years on. It shows the value people placed on justice; his single life was worth fighting for even as the Normandy landings and V1 attacks in London and the south east made death and devastation commonplace. It also reminds us of the power of the tabloid press which was then a noisy champion of social justice and went to play a leading part in the 1945 general election. It tells us that race – and racism – was as much a factor on the home front as the front line against the racially supremacist Nazis. Ultimately it draws a line, however faint, from then to now. Maybe we could see ourselves in those who fought for Leroy Henry – or at least that’s what we could aspire to in our increasingly divided world.

Kate Werran at Bude Literary Festival in May 2024. Photo: David WerranInstead, readers should see reactions to miscarriages of justice against African American servicemen such as Leroy Henry as catalysts in the civil rights struggle; moments that made the US rethink its policy on segregation and race. In the US Army’s own account of its history, the British response to the ‘Negro problem’ was ‘unique’ because the ‘usual friction’ was exacerbated by a ‘lack of racial discrimination by the British people’. Would any other population have reacted to the death sentence in the same way – making the US Army rethink Leroy Henry’s sentence? And ultimately segregation? I think cases like Leroy Henry’s show British society in a remarkably ‘modern’ light which is perhaps less familiar to us eighty years on. It shows the value people placed on justice; his single life was worth fighting for even as the Normandy landings and V1 attacks in London and the south east made death and devastation commonplace. It also reminds us of the power of the tabloid press which was then a noisy champion of social justice and went to play a leading part in the 1945 general election. It tells us that race – and racism – was as much a factor on the home front as the front line against the racially supremacist Nazis. Ultimately it draws a line, however faint, from then to now. Maybe we could see ourselves in those who fought for Leroy Henry – or at least that’s what we could aspire to in our increasingly divided world.

After ‘An American Uprising’ this is your second book about African-Americans in the UK. Do you have any new projects coming up and would you be willing to share anything about it with our readers?

There’s lots going on right now – and an awful lot of planning going on! I am hoping to start my Phd in this area soon — I also have another controversial court martial in Britain in 1944 that I am keen to research and explore. There are probably three more book ideas I’ve got from the archives this time – and then I want to write a screenplay for this and my previous book. I am also planning a podcast series with my amazing friend Neil McCallum – who writes historical fiction under the name Dawood Ali McCallum. So a lovely to do list that I can’t wait to start!

Segregated US troops at Bodmin Camp, Cornwall 1944. Courtesy of Kresen Kernow, E8681 George Ellis Collection

Segregated US troops at Bodmin Camp, Cornwall 1944. Courtesy of Kresen Kernow, E8681 George Ellis CollectionWhen did you first hear of Leroy Henry and what made you decide to write a book about him?

I first heard about Leroy Henry when researching my first book into the mutiny of an African American ordinance unit based in my Dad’s home town in Cornwall in 1943 (An American Uprising in Second World War England: Mutiny in the Duchy, Pen & Sword 2020). Leroy Henry was mentioned in Graham Smith’s book When Jim Crow met John Bull and has been the subject of a couple of academic papers by Professor Mary Louise Roberts and a few features online. But there’s never been a full examination of the story – including the context of what else was going on in the UK and testimony from local people who signed the petition and campaigned for Leroy Henry. By the time American Uprising was published, it just so happened that my family and I had moved back to Bath – and it seemed crazy for me not to look into the story a bit more carefully and talk to those who remembered it while there was still time.

In which army unit did Leroy Henry serve and have you been able to extract his personal background?

Corporal Leroy Henry (Technician Fifth Grade) served in the 3914th Quartermaster Gasoline Supply Company while he was in the UK. Although born in Des Arc, Arkansas, he was living in Missouri in 1940 and working as a labourer, according to the census. He named his aunt as closest living relative on his enlistment card. By the time he moved overseas to the UK he was married and employed as a truck driver with the QM company he served.

4. Knook Camp near Warminster in Wiltshire where Leroy Henry was court-martialled in May 1944. Photo: Kate Werran

4. Knook Camp near Warminster in Wiltshire where Leroy Henry was court-martialled in May 1944. Photo: Kate WerranLeroy Henry was one of many African-American servicemen who were stationed in the United Kingdom in the prelude to D-Day, 6 June 1944. In their homeland they were discriminated against, but how were they treated by the British population?

The British people welcomed African American servicemen with open arms, much to the disgust of some white GIs. Although Britain then had an empire including many millions of people of colour, the Black British population was very small – maybe 15,000 which was based mostly in the port cities of London, Bristol and Cardiff. Obviously there was racism in Britain at that time and this was definitely more the case with upper rather than lower classes, but when segregation and its inherent racism came over in American troopships during the time Britain was ‘occupied territory’ (according to George Orwell) — it sparked a vigorous reaction. The US Army’s segregation (which mimicked the ‘Jim Crow’ separation of society in the American South) quite simply offended everyday people. The archives are full of criticisms and questions as to why African Americans should be treated any differently to the Polish, Czech and French people living in Britain and preparing for D-Day. British people resisted segregation and refused to allow it in dance halls, pubs and buses and trains. And there is mountains of evidence in newspapers, diaries, government morale reports and soldiers’ letters home to America that when violence spilled over on British soil, the Brits backed the African Americans, from a ‘fairness’ point of view more than anything else. It just didn’t wasn’t cricket to treat them any other way.

What and by whom was Leroy Henry accused and was he given a fair trial?

Execution shed at Shepton Mallet Prison that was revamped when the US Army took it over in 1942. Photo: Kate Werran

Execution shed at Shepton Mallet Prison that was revamped when the US Army took it over in 1942. Photo: Kate WerranThe United States of America (Visiting Forces Act) 1942 ensured that any crime committed by an American citizen in the UK during WW2 was to be dealt with by US military justice rather than British law. So three weeks later, Leroy Henry was moved to Knook Camp in Wiltshire for his US Army court martial. The prosecution’s case hinged on Henry’s confession to raping a stranger at knife point. But there were gaping holes in the argument. The victim could not identify his face, there was no evidence of rape on either the victim or Henry, no knife was ever found despite two inch-by-inch searches of the scene and the victims and husbands’ alibis for their whereabouts at various points did not tally. Leroy Henry’s defence maintained that his confession had been made under duress – he had not slept or been offered anything to eat or drink; he had fainted and been hit and the statement he signed was written by his interrogators. Not only did Leroy Henry not know what he signed his name to, it is uncertain he actually knew the meaning of the word ‘rape’. He argued that this was his third meeting with the woman. Each previous occasion he had paid her money for sex that had been pre-arranged earlier in the evenings, but this time she had been startled by the sudden appearance of her husband on the scene. Despite all this, the army panel found Leroy Henry guilty and sentenced him to death.

How did the British public and press react to the persecution of Leroy Henry?

After Leroy Henry had been given the death sentence there was a brief hiatus until news of the sentence reached local papers three days later. When it did, the reaction was immediate. 200 of the victim’s immediate neighbours and those who lived around the village common (where the assault is alleged to have taken place) signed a petition protesting Leroy Henry’s treatment. They said no screams or untoward sounds were heard on the village common on the night in question. Jack Allen, who owned a transport café in Bath, was outraged and along with his great friend Sam Day, an alderman, established a petition to demand clemency for the African American soldier. There was a general sense of anger that Henry had been sentenced to death for rape in Britain when it wasn’t a capital offence here in 1944 – nor had it been for more than 100 years. It underlined the fact that an alien law was at work. Claiming the issue would unite every class in Bath, they gave themselves eight days to show the strength of feeling. People went door-to-door collecting signatures, petition points sprang up all over the city. Those who still remember the furore say that things simply ‘snowballed’. The Daily Mirror meanwhile — then the most popular and best-read tabloid with a readership of millions — championed Leroy Henry’s case in a news report and then (four days before D-Day) with an impassioned editorial leader begging for clemency. By D-Day itself more than 18,000 had signed the petition. Letters were sent to General Eisenhower, the US Ambassador, the Home Secretary and various members of parliament. Other national and local newspapers picked up the story. Thurgood Marshall of the NAACP demanded a stay of execution, followed by its British equivalent; The League of Coloured Peoples (LCP). Resistance to Leroy Henry’s plight was at once rooted both in Bath (and its surrounding towns and villages) – and the nation. By D-Day +1 another 12,000 names had been added and by 12pm on 8 June 1944 the closing number was 33,132.

What role does the issue of Leroy Henry play in the history of the civil rights movement?

At least two American academics believe this episode changed America. Professor Mary Louise Roberts cites it as one of the 25 moments that defined/changed America – the precise point when ‘Jim Crow’ treatment became publicly unacceptable to the world. Professor J Robert Lilly defines this as when the US Army realised the narrative needed to change. Incidents like Leroy Henry’s case and other armed confrontations such as the mutiny of African American servicemen in Launceston, Cornwall and the lethal shoot-out in Bamber Bridge, caused the NAACP’s Walter White to come to Britain to investigate. White repeatedly lobbied for the US Army to be integrated – which was surely a pre-requisite for the integration of American society in the southern states. How could Southern society’s separation end while a segregated army still survived?

African American minesweepers in the UK. Courtesy of the National Archives of America, photo no 111-SC-181889

African American minesweepers in the UK. Courtesy of the National Archives of America, photo no 111-SC-181889What happened to Leroy Henry after the Second World War?

Henry was promoted to sergeant and honourably discharged in 1946. He died in 1971 with no dependants and his occupation was listed as a cobbler. He is buried at the National Cemetery at Jefferson Barracks, Missouri.

What can today's readers learn from the injustice done to Leroy Henry and other ‘black yanks’?

Certain British TV commissioning editors feel cases like Leroy Henry’s prove Winston Churchill was the architect of a ‘secret apartheid state’ in the Second World War and there is at least one documentary in the pipeline with this thesis. I think this misses the point; it masks its true historical significance and traduces the efforts of those who fought so hard for the ‘Black Yanks’ they came to champion.

Kate Werran at Bude Literary Festival in May 2024. Photo: David Werran

Kate Werran at Bude Literary Festival in May 2024. Photo: David WerranAfter ‘An American Uprising’ this is your second book about African-Americans in the UK. Do you have any new projects coming up and would you be willing to share anything about it with our readers?

There’s lots going on right now – and an awful lot of planning going on! I am hoping to start my Phd in this area soon — I also have another controversial court martial in Britain in 1944 that I am keen to research and explore. There are probably three more book ideas I’ve got from the archives this time – and then I want to write a screenplay for this and my previous book. I am also planning a podcast series with my amazing friend Neil McCallum – who writes historical fiction under the name Dawood Ali McCallum. So a lovely to do list that I can’t wait to start!

- Black Yanks

- Defending Leroy Henry in D-Day Britain

- ISBN: 9781803993522

- More information about this book

Used source(s)

- Source: Kate Werran / TracesOfWar

- Published on: 07-07-2024 11:28:36

Related news

- 23-06: Keeping the memory of the trails to freedom alive

- 12-04: Understanding the German side of the fighting in Normandy

- 11-'24: Postal artifacts provide a vibrant testament to the experiences of the Dutch people during WWII

- 10-'24: DigitalBattlefieldTours unlocks military tactics to a wide audience

- 08-'24: Researching his father’s WWII history became a passion for Steve Snyder

Latest news

- 03-10: Photo report other Airborne commemorations and events 2025

- 01-10: Photo report commemoration Wiltshire memorial

- 30-09: Photo report other Airborne commemorations and events 2025

- 26-09: Photo report Ounveiling Plaque 'Gunners within 1st Airborne Division'

- 25-09: Photo report unveiling Plaque 'Gunners within 1st Airborne Division'

- 24-09: Photo report Airborne commemoration Driel

- 23-09: Photo report Airborne Landing and Commemoration

- 22-09: Photo report Airborne Memorial Service Oosterbeek

- 23-06: Keeping the memory of the trails to freedom alive

- 12-04: Understanding the German side of the fighting in Normandy