Postal artifacts provide a vibrant testament to the experiences of the Dutch people during WWII

What is The Arnhem Postal History Collection and Digital Archives (APH) and what’s your connection to it?

My name is Tim Gale and I am the Director of the Arnhem Postal History (APH) Collection and Digital Archives project, a non-profit entity, currently based in the United States of America. The APH project examines the intersection of social and military history and the role of the postal service during the Battle of Arnhem, and more broadly World War II in Holland, where postal artifacts provide direct firsthand, contemporaneous records of the civilian and social impact of the brutal battles that have become so well known to many.

The APH collection uses primary sources, including correspondence, to offer first-person accounts of the everyday lives and experiences of Dutch civilians, military combatants and others, who witnessed key moments during World War II. This unique collection comprises over 9,000 individual letters and postcards circulated inside and outside the Netherlands between 1939 and 1945, as well as official correspondence, propaganda, personal memoirs, and other important artifacts.

The original letters and correspondence in the collection provide researchers with contemporaneous insight to the experiences of the local population during wartime. APH offers powerful first-person accounts of the Dutch population enduring life under occupation for almost the entire duration of World War II. These accounts add to a holistic, and at the same time, intimate understanding of the war’s lasting impact.

Arnhem Postal History started as a “pandemic” project. I have long been interested in WW2 and had spent decades reading about and researching the Holocaust. While I have no personal connection to the Holocaust, I was deeply moved by the stories of suffering and defiance, noting that this was not a military battle, but rather an all-out assault on individual civilians, families and even complete communities. But after a while, I became overwhelmed by all of the suffering, and I needed to take a break. Then on 17 September 2019, I saw the film “A Bridge Too Far”’ on television. I had seen the Hollywood blockbuster several times before, but as I watched it again, I remember thinking “how realistic is it?” Anthony Beevor had published a book on Arnhem, which I then read. I have since read several hundred books on the topic!

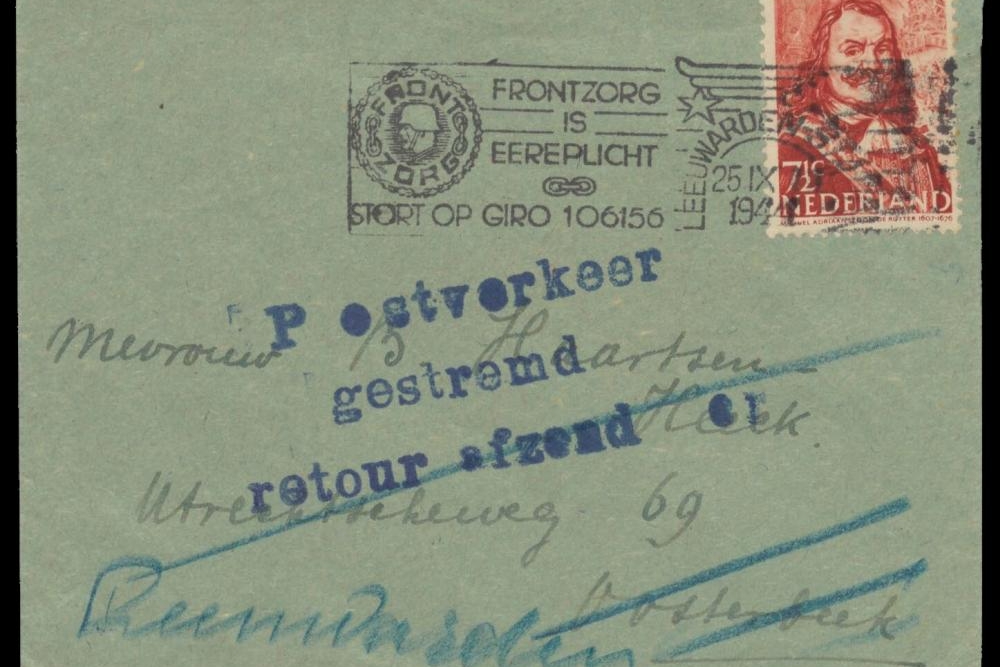

My interest would probably have stopped there, but a dear friend, who is an internationally renowned philatelist, gave me an envelope (a “cover” in philatelist parlance) that was addressed to Mevrouw B. Haartsen-Heeck at Utrechtsweg 69, Oosterbeek, dated 25 September 1944. The letter was clearly stamped “Postverkeer / gestremd / retour afzend” (Postal traffic / obstructed / return sender), which was not surprising given the address (her home was located right on the front line of the battle between the 1st British Airborne Division and assorted German forces) and it started me thinking about who this lady was, hiding in her basement, while the fiercest day of the fighting raged around her.

Letter addressed to Mrs. B. Haartsen-Heeck, Utrechtseweg 69, Oosterbeek, dated September 25, 1944. Source: Arnhem Postal History

Letter addressed to Mrs. B. Haartsen-Heeck, Utrechtseweg 69, Oosterbeek, dated September 25, 1944. Source: Arnhem Postal HistoryMy “pandemic project” has now grown into a collection of over 9,000 postal items sent throughout Holland during the five years of war (1940-1945). Clearly, not all items within our collection are specific to Arnhem, nor do they all fall within the time frame of the battle, but many of them contribute to an understanding of a Dutch population enduring one of the most fierce battles of World War II, as it was fought in their homes and gardens.

How would you describe the exhibition ‘The Battle of Arnhem - September 17-25, 1944: False Hope and Lasting Thanks’? In what ways is it innovative or different from other exhibitions?

This exhibit uses philatelic material and other contemporary artifacts to tell the personal stories of individuals and families whose lives were caught up in the one of the most renowned battles of World War II. The Battle of Arnhem started with great hope, both among the Allied military and the Dutch civilian population, who believed that liberation from the Nazis was at hand (“False Hope”).

In the immediate aftermath of the battle, the Wehrmacht ordered almost 150,000 residents of Arnhem and surrounding villages to evacuate and then engaged in mass looting of local residences and businesses. However, despite the subsequent failure at Arnhem, the local Dutch population has continued to honor and remember the British and Polish airborne troops, welcoming back veterans and holding annual memorials (“Lasting Thanks”). It is this continued appreciation of what the airborne troops tried, but failed to achieve, that continues to amaze me, despite the horrific impact it had on the civilian population!

The exhibition includes several letters from Dutch citizens. Was it possible for them to send and receive mail during the Battle of Arnhem? What information can be extracted from their correspondence?

The exhibit’s subject matter presented unique challenges. The battle lasted nine days, during which time the local population understandably took shelter from the fighting. Communication into and out of the city came to a standstill. Before the battle had concluded and with no advance warning, the Nazis forced the entire local population to evacuate the city and surrounding areas and then set out about a systematic looting of personal and business property. As a result, many personal artifacts were abandoned, resulting in a scarcity of surviving material. Personal papers, including letters, were routinely destroyed.

Nonetheless, the available postal artifacts form a uniquely rich and important part of the historical record. They provide firsthand, individualized accounts of the social impact of the brutal events and circumstances of the war in Holland. Almost by definition, postal artifacts include information on the sender, as well as the recipient; the cover is inscribed with precise information about the date that it was sent, and the timing and route that it took until delivered (or otherwise handled). As such, postal artifacts provide a vibrant, structured testament to the experiences of the Dutch people during World War II.

The project seeks to combine the terrified life of Dutch civilians, hiding in their basements, with the raw experiences of the well trained, young airborne soldiers who fought at Arnhem. The battle was fought from house to house, door to door, whether at the bridge or around the perimeter. Every one of those houses had a mail slot and as the following photograph, taken in Ede in 1944, so clearly shows, the Dutch Postal Service (PTT) were determined to keep the post open, providing the average person’s only means of communication.

Postal delivery by the PTT in 1944 , Ede. Source: Arnhem Postal History

Postal delivery by the PTT in 1944 , Ede. Source: Arnhem Postal HistoryWhich part or story in the exhibit do you personally find most interesting or touching?

There a number of stories that I find particularly powerful. For example, I am struck by the story of the Roza family. Huib Roza, his wife Riek and their daughter, Lientje lived at Parallelweg 50 in Oosterbeek. Their house was caught in the crossfire between the Germans in de Spoorberg and men from the King’s Own Scottish Borderers at Huize Dennenkamp. The detailed content of the Roza’s letters offers a direct and intimate insight into the shared experience of civilians, hiding in a cellar while the fighting raged on all around them. I suspect that many families are experiencing similar difficulties in Ukraine today.

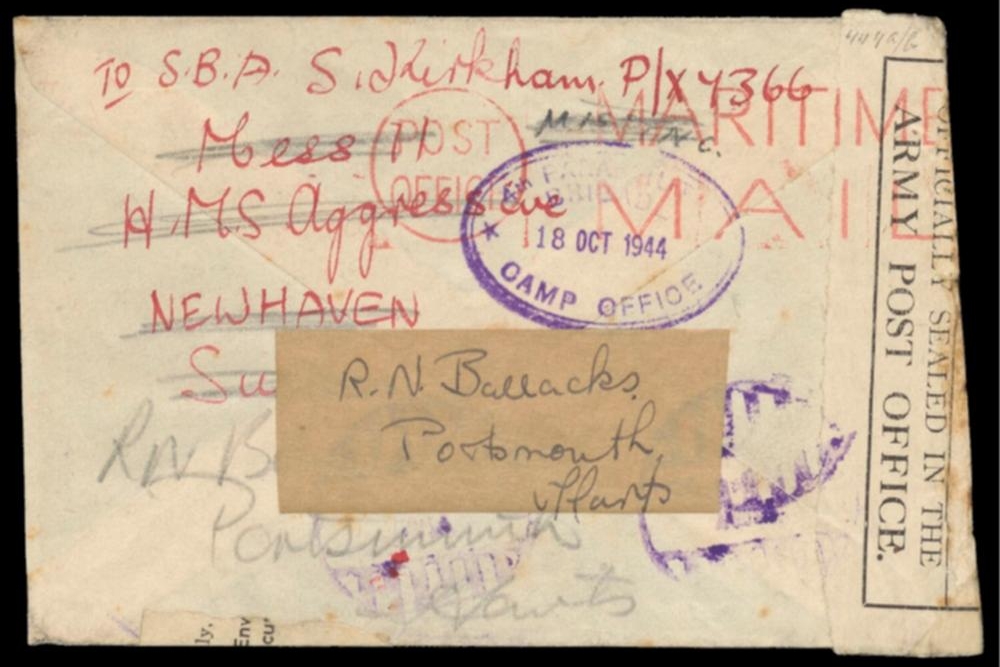

I am also impacted by the story of Private Harold Kirkham, 4th Brigade Defense Platoon. He was born on 24 April 1914 (which also happens to be my birthday), son of Alfred and Elizabeth Ann Kirkham of Bolton, UK. His brother, Sidney, a Sick Berth Attendant with HMS Aggressive, wrote to Harold on 24 September 1944, but the letter was returned on 18 October 1944, stamped in the field by what little remained of4th Brigade HQ. It indicated that Harold Kirkham was reported missing. In fact, Harold had been killed in fierce fighting in the woods along the Valkenburglaan. This place would later be known as 'Hacket’s Hollow'. Despite our best efforts, we have not been able to find any surviving relatives of Harold or Sidney Kirkham. The simple cover is the only connection that remains to either brother and, if not for this project, I suspect that Harold Kirkham’s name would have been lost for all time.

Letter to Private Harold Kirkham of the 4th Brigade Defense Platoon. Source: Arnhem Postal History

Letter to Private Harold Kirkham of the 4th Brigade Defense Platoon. Source: Arnhem Postal HistoryThe exhibit also pays attention to the aftermath of the Battle of Arnhem. In what ways? What role does the Red Cross play in this part of the exhibition?

After Operation Market Garden, Dutch railway personnel remained on strike for the remainder of the war. As a result, postal service was severely restricted because trains and postal vans were no longer available. However, the Red Cross was initially able to transport mail. For example, after Arnhem was ordered evacuated on 23 September, many refugees wound up in nearby Velp. After just one day, the mayor of Velp realized they could not handle any more evacuees and he sent new arrivals to Rheden, Ellecom and Dieren. Rheden (10 miles east of Arnhem) was situated in the German defense zone and the population had not been evacuated. Its Red Cross branch performed a crucial role carrying mail to those towns and villages in the German sector, where it could still be delivered locally. Red Cross assistance with mail delivery often occurred without any involvement from the Dutch postal service (PTT). At other times, the Red Cross only delivered an item to the addressee at the end stage.

The German Red Cross Tracing Service performed a valuable service after the war, collecting written declarations from German soldiers returning home from POW camps or prisons. In them, they provided information about soldiers in their former units who were still classed as missing in action.

In your exposition, the German word Überroller appears. Can you explain this term?

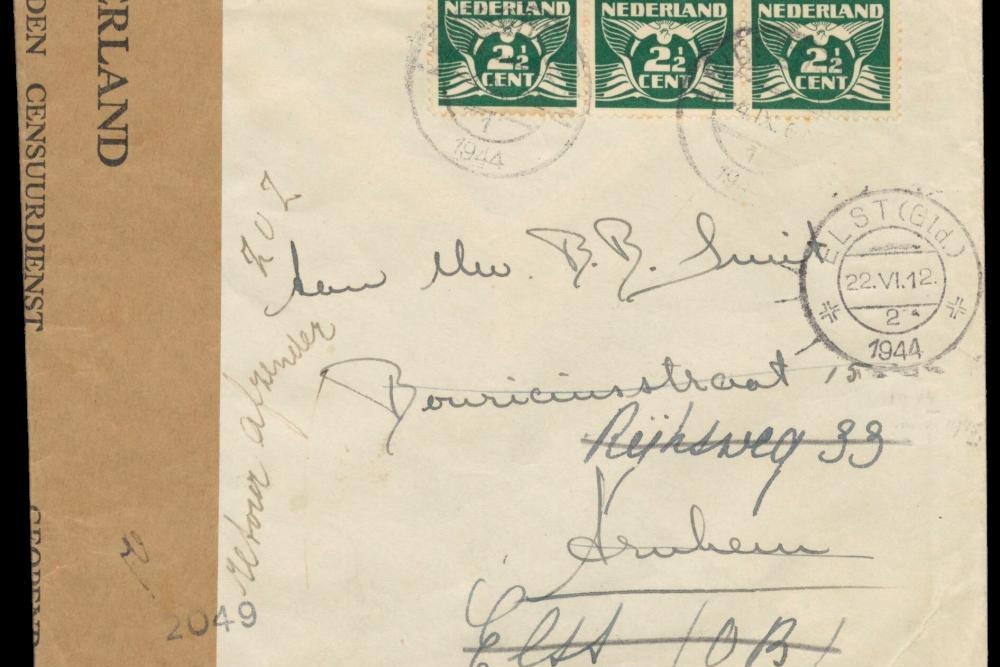

An “Überroller” is an item of mail that was posted during one regime, then confiscated and processed by another. For example, many letters were sent from the south to the north of Holland during Operation Market Garden. These letters were sent from towns which were under German control, but then as the battle front moved northwards and towns were liberated, the mail would be held up by the Allies and final delivery would only be completed after the Allies had also liberated the destination.

For example, the letter shown on Page 28 of the exhibit was mailed in Ede (GL) on 15 September 1944 and forwarded to Elst (GL). It was then confiscated by the Allies and censored by the Dutch censor in Eindhoven. After the war, it was finally delivered to the addressee in Elst on 22 June 1945.

Example of a so-called "Überroller". Source: Arnhem Postal History

Example of a so-called "Überroller". Source: Arnhem Postal HistoryThere are also many photographs and film footage of the Battle of Arnhem. And nowadays museums are using multimedia in abundance. Yet the emphasis of your exhibition is on paperwork. Do you think this will still affect modern museum visitors?

Handwritten notes, letters and even books, are fast being replaced by a digital world, with seemingly unlimited amounts of information (and disinformation) available on demand. While the digital is infinitely reproducible, the older analog world is fast losing its remaining artifacts with fewer and fewer replacements available. It is APH’s intention to focus at the junction of the analog and the digital and establish an interactive “journey” where students and others can follow a number of authentic, but very “old world” analog postal artifacts, as they travel through the Dutch countryside and the duration of somee of the best documented battles.

Postal artifacts form a uniquely rich and important part of the historical record. They provide firsthand, individualized accounts of the social impact of the brutal events and circumstances of the war in Holland. Almost by definition, postal artifacts include information on the sender, as well as the recipient; the cover is inscribed with precise information about the date that it was sent, and the timing and route that it took until delivered (or otherwise handled). As such, postal artifacts provide a vibrant, structured testament to the experiences of the Dutch people during World War II.

The Arnhem Postal History Collection is working to digitize the entire collection and make it available as a searchable digital archive, freely available to the public and historical researchers. The online collection will include multimedia interactive tools which will trace the path of letters and other items of mail as they pass through the Dutch countryside. If you would like to access a beta, online version of the collection and archives, please visit: http://arnhempostalhistory.org.

Are you already working on a new exhibition and when and where will it be shown?

The APH collection currently features a series of five exhibits:

- Code Yellow and the 1940 German invasion of Holland

- Evolution of the Holocaust in Holland

- Battle of Arnhem: False Hopes and Lasting Thanks

- Battle of the Scheldt and the Hunger Winter (available 2025)Life under Occupation (available 2025)

The last two exhibits are currently in production and will be available in 2025.

Used source(s)

- Source: Tim Gale / TracesOfWar

- Published on: 02-11-2024 21:07:52

Related news

- 10-'24: DigitalBattlefieldTours unlocks military tactics to a wide audience

- 08-'24: Researching his father’s WWII history became a passion for Steve Snyder

- 08-'24: Who was the owner of the photo album from Dachau?

- 07-'24: The British people welcomed African American servicemen with open arms

- 06-'24: "There seems to never be an end to cool historic places to cover"

Latest news

- 03-03: A WWII helmet returns home 80 years after having been lost at Remagen Bridge, Germany

- 16-02: Armin T. Wegner and his letter to Hitler

- 14-02: The hugely popular ‘Standing with Giants’ installation returns to the British Normandy Memorial

- 27-01: Russia focuses on Soviet victims of WW2 as officials not invited to Auschwitz ceremony

- 27-01: Oswald Kaduk, ‘Papa Kaduk’ or a monster??

- 12-'24: Christmas and New Year message from our volunteers

- 11-'24: New book: Righteous Behind Barbed Wire

- 10-'24: DigitalBattlefieldTours unlocks military tactics to a wide audience

- 10-'24: Lily Ebert, Holocaust Survivor, Author and TikTok Star, Dies at 100

- 10-'24: Commemoration 7th Battalion the Hampshire regiment