Unmarked graves of the only British soldiers who died in Germany between WW1 & WW2

As the long period of public remembrance and reflection marking the centenary of the outbreak and the bloody course of WW1 comes to an end, it is worth highlighting a particular commemorative plight arising from the British government’s decision to determine 31 August 1921 as the official end of the war. This is an account of the British Army’s indifference to the plight of the only British soldiers, 30 of them, who died in Germany whilst implementing conditions of the Treaty of Peace, and who lie buried in Europe without any form of commemoration or recognition.

Written by: Jim Powrie

But what happened on 1 September 1921? Did the British military simply stop what it was doing and come home or were there other areas of continuing conflict and tension relating to the Great War? The answer of course is that there were still many flashpoints that required Allied, and British military intervention.

There was a large British army of occupation in Germany with its base in Cologne, the British Army of the Rhine (BAOR), and residual forces in Turkey, Mesopotamia, Egypt and Palestine amongst other places.

An example of ongoing British army action was in 1921 in Upper Silesia, an area of Central Europe partly in Poland and partly in Germany. Under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles that was signed in 1919, Germany was stripped of about 25,000 square miles (65,000 km2) of territory and nearly 7,000,000 people. In Eastern Europe, Germany had to recognize the independence of Poland and renounce "all rights and title over the territory". Portions of the province of Upper Silesia that was ethnically divided between peoples of Polish and Germanic descent, were to be ceded directly to Poland, with the future of the rest of the province to be decided by plebiscite. The border would be fixed with regard to the vote and to the geographical and economic conditions of each locality.

In 1920, under the auspices of The League of Nations, the fore-runner of today’s United Nations Organisation, The Inter-Allied Commission for Upper Silesia was formed comprising of representatives from France, Britain and Italy to administer the plebiscite that was to take place in 1921, and the newly created borders that would result from the outcome of the vote. A military force was assembled, and the boots on the ground, were supplied primarily, by the French, with troops from the British Rhine Army and Italian forces arriving in greater numbers in 1921. Inter-ethnic tensions by this time were high within the population, resulting in a great deal of unrest and violence between the people. There was also some mistrust and antagonism shown towards some sections of the military personnel of the Inter-Allied Commission who were largely employed as a ‘peace keeping’ force.

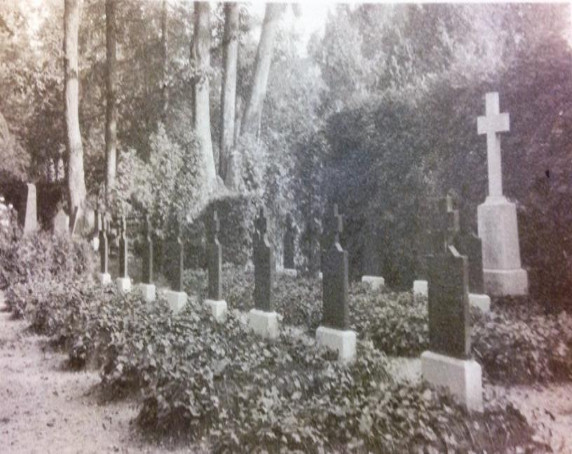

The British contingent was deployed in the area from May 1921 until July 1922 and during that period 41 soldiers of the British army were killed or died whilst on active duty. Every one of them was given a full ‘service’ funeral and they were buried side by side in the British military section of the Oppeln Municipal Cemetery. British Army wooden crosses, supplied from British Army stores were erected over each grave. Significantly, 11 of these men died before 31 August 1921 and were considered ‘war dead’, with the remaining 30 dying between September 1921 and July 1922 when the British forces were withdrawn from Upper Silesia.

In late 1924 the 11 British ‘war dead’ were exhumed from the cemetery by the Imperial War Graves Commission (IWGC) and transported to Berlin where they were reinterred in the Berlin South Western War Cemetery at Stahnsdorf where they remain today in beautifully kept surroundings. The IWGC had suggested to the Army Command that it could exhume the 30 ‘post-war’ dead and either transport them to Berlin for reinternment or could transport them to Cologne for reinternment in the section of the Sudfriedhof cemetery that had already been allocated to the burial of British post-war graves. On the grounds of cost, the Army declined to accept the offer.

For the next 6 years the graves of the men in Oppeln were completely neglected by the British authorities and through utter disregard and neglect, the wooden crosses had deteriorated to such an extent that the German cemetery authorities wrote to the Army imploring them to do something, but with no commitment being received, the German authorities took it upon themselves to restore the dignity of the dead by providing, at their own expense, permanent headstones in the form of cast-iron crosses.

During the inter-war period in Germany, the Army Council did not consider that it should bear the responsibility for military burials or those of service dependents that occurred during the occupation of the Rhineland or during the deployment in Upper Silesia. There is much archival correspondence relating to this matter, but the outcome was that up until the outbreak of WW2, the 129 military (+199 civilian) burials in Cologne, the 58 military (+74 civilian) burials in Wiesbaden and the 30 military burials in Oppeln would be maintained and paid for by the Army. Thus, in all three cases arrangements were made either with the local authority (in Oppeln and Wiesbaden) or the IWGC in Cologne for maintenance of the cemeteries.

Things changed after WW2. Oppeln, which had been in pre-war Weimar Germany, was now in post-war Poland and known as Opole, and whilst the pre-war maintenance arrangements were re-instated and enhanced for both Cologne and Wiesbaden cemeteries (including the replacement and provision of new headstones), Oppeln/Opole was, to all intents and purposes, forgotten.

In October 1959, the IWGC wrote to the War Office reminding it of the existence of the cemetery in Opole, and that up until 1939 it had a responsibility under the pre-war agreement to inspect the plot. The War Office wrote to the Military Attaché at the British Embassy in Warsaw requesting the provision of details of the cemetery. The Military Attaché’s reply was dismissive, bordering on negligent, as he made no attempt to ascertain the status of the cemetery and simply replied:

“There is only one British cemetery in this part of Poland, namely at KRAKOW”.

And that’s where the matter ended. The War Office did not reply to the IWGC regarding further maintenance of the cemetery, and the IWGC took no further action.

Recent communication with the Ministry of Defence highlighting the plight of the 30 ‘forgotten’ men initially elicited a stock answer outlining the MoD’s policy on inter-war graves that responsibility for service burials reverted to the pre-1914 arrangement whereby regiments and units buried their own dead without central assistance, but there is extensive archival correspondence giving details of unambiguous and indisputable evidence contained within contemporary files held in The National Archives, that the Army Council had, as a matter of policy, considered the 30 men in Oppeln to be a ‘special case’. Provision of this undeniable evidence has not persuaded the MoD to review its current stance as it still refuses to re-instate the pre-war arrangement for Opole as it has done for both Cologne and Wiesbaden.

It has been brought to the attention of the MoD that if it were to request the CWGC to include these men in the same way that it has the 187 servicemen in Cologne and Wiesbaden, funding for 30 new headstones is available from the special fund set up by

the Government when fines imposed after the ‘Libor’ rate fixing scandal were given to the CWGC for projects such as this.

But MoD indifference and intransigence to accept any sort of responsibility means that there are 30 British soldiers who died whilst serving King and Country lying in a cemetery in Poland with nothing above them other than grass.

It is a disgrace.

Written by: Jim Powrie

But what happened on 1 September 1921? Did the British military simply stop what it was doing and come home or were there other areas of continuing conflict and tension relating to the Great War? The answer of course is that there were still many flashpoints that required Allied, and British military intervention.

There was a large British army of occupation in Germany with its base in Cologne, the British Army of the Rhine (BAOR), and residual forces in Turkey, Mesopotamia, Egypt and Palestine amongst other places.

An example of ongoing British army action was in 1921 in Upper Silesia, an area of Central Europe partly in Poland and partly in Germany. Under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles that was signed in 1919, Germany was stripped of about 25,000 square miles (65,000 km2) of territory and nearly 7,000,000 people. In Eastern Europe, Germany had to recognize the independence of Poland and renounce "all rights and title over the territory". Portions of the province of Upper Silesia that was ethnically divided between peoples of Polish and Germanic descent, were to be ceded directly to Poland, with the future of the rest of the province to be decided by plebiscite. The border would be fixed with regard to the vote and to the geographical and economic conditions of each locality.

In 1920, under the auspices of The League of Nations, the fore-runner of today’s United Nations Organisation, The Inter-Allied Commission for Upper Silesia was formed comprising of representatives from France, Britain and Italy to administer the plebiscite that was to take place in 1921, and the newly created borders that would result from the outcome of the vote. A military force was assembled, and the boots on the ground, were supplied primarily, by the French, with troops from the British Rhine Army and Italian forces arriving in greater numbers in 1921. Inter-ethnic tensions by this time were high within the population, resulting in a great deal of unrest and violence between the people. There was also some mistrust and antagonism shown towards some sections of the military personnel of the Inter-Allied Commission who were largely employed as a ‘peace keeping’ force.

The British contingent was deployed in the area from May 1921 until July 1922 and during that period 41 soldiers of the British army were killed or died whilst on active duty. Every one of them was given a full ‘service’ funeral and they were buried side by side in the British military section of the Oppeln Municipal Cemetery. British Army wooden crosses, supplied from British Army stores were erected over each grave. Significantly, 11 of these men died before 31 August 1921 and were considered ‘war dead’, with the remaining 30 dying between September 1921 and July 1922 when the British forces were withdrawn from Upper Silesia.

In late 1924 the 11 British ‘war dead’ were exhumed from the cemetery by the Imperial War Graves Commission (IWGC) and transported to Berlin where they were reinterred in the Berlin South Western War Cemetery at Stahnsdorf where they remain today in beautifully kept surroundings. The IWGC had suggested to the Army Command that it could exhume the 30 ‘post-war’ dead and either transport them to Berlin for reinternment or could transport them to Cologne for reinternment in the section of the Sudfriedhof cemetery that had already been allocated to the burial of British post-war graves. On the grounds of cost, the Army declined to accept the offer.

For the next 6 years the graves of the men in Oppeln were completely neglected by the British authorities and through utter disregard and neglect, the wooden crosses had deteriorated to such an extent that the German cemetery authorities wrote to the Army imploring them to do something, but with no commitment being received, the German authorities took it upon themselves to restore the dignity of the dead by providing, at their own expense, permanent headstones in the form of cast-iron crosses.

During the inter-war period in Germany, the Army Council did not consider that it should bear the responsibility for military burials or those of service dependents that occurred during the occupation of the Rhineland or during the deployment in Upper Silesia. There is much archival correspondence relating to this matter, but the outcome was that up until the outbreak of WW2, the 129 military (+199 civilian) burials in Cologne, the 58 military (+74 civilian) burials in Wiesbaden and the 30 military burials in Oppeln would be maintained and paid for by the Army. Thus, in all three cases arrangements were made either with the local authority (in Oppeln and Wiesbaden) or the IWGC in Cologne for maintenance of the cemeteries.

Things changed after WW2. Oppeln, which had been in pre-war Weimar Germany, was now in post-war Poland and known as Opole, and whilst the pre-war maintenance arrangements were re-instated and enhanced for both Cologne and Wiesbaden cemeteries (including the replacement and provision of new headstones), Oppeln/Opole was, to all intents and purposes, forgotten.

In October 1959, the IWGC wrote to the War Office reminding it of the existence of the cemetery in Opole, and that up until 1939 it had a responsibility under the pre-war agreement to inspect the plot. The War Office wrote to the Military Attaché at the British Embassy in Warsaw requesting the provision of details of the cemetery. The Military Attaché’s reply was dismissive, bordering on negligent, as he made no attempt to ascertain the status of the cemetery and simply replied:

“There is only one British cemetery in this part of Poland, namely at KRAKOW”.

And that’s where the matter ended. The War Office did not reply to the IWGC regarding further maintenance of the cemetery, and the IWGC took no further action.

Recent communication with the Ministry of Defence highlighting the plight of the 30 ‘forgotten’ men initially elicited a stock answer outlining the MoD’s policy on inter-war graves that responsibility for service burials reverted to the pre-1914 arrangement whereby regiments and units buried their own dead without central assistance, but there is extensive archival correspondence giving details of unambiguous and indisputable evidence contained within contemporary files held in The National Archives, that the Army Council had, as a matter of policy, considered the 30 men in Oppeln to be a ‘special case’. Provision of this undeniable evidence has not persuaded the MoD to review its current stance as it still refuses to re-instate the pre-war arrangement for Opole as it has done for both Cologne and Wiesbaden.

It has been brought to the attention of the MoD that if it were to request the CWGC to include these men in the same way that it has the 187 servicemen in Cologne and Wiesbaden, funding for 30 new headstones is available from the special fund set up by

the Government when fines imposed after the ‘Libor’ rate fixing scandal were given to the CWGC for projects such as this.

But MoD indifference and intransigence to accept any sort of responsibility means that there are 30 British soldiers who died whilst serving King and Country lying in a cemetery in Poland with nothing above them other than grass.

It is a disgrace.

| You can sign Jim Powrie's petition here! |

Used source(s)

- Source: Jim Powrie

- Published on: 01-07-2019 20:47:58

Latest news

- 03-03: A WWII helmet returns home 80 years after having been lost at Remagen Bridge, Germany

- 16-02: Armin T. Wegner and his letter to Hitler

- 14-02: The hugely popular ‘Standing with Giants’ installation returns to the British Normandy Memorial

- 27-01: Russia focuses on Soviet victims of WW2 as officials not invited to Auschwitz ceremony

- 27-01: Oswald Kaduk, ‘Papa Kaduk’ or a monster??

- 12-'24: Christmas and New Year message from our volunteers

- 11-'24: New book: Righteous Behind Barbed Wire

- 11-'24: Postal artifacts provide a vibrant testament to the experiences of the Dutch people during WWII

- 10-'24: DigitalBattlefieldTours unlocks military tactics to a wide audience

- 10-'24: Lily Ebert, Holocaust Survivor, Author and TikTok Star, Dies at 100