The War at Sea

By Francis E. McMurtrie.

The War Illustrated, Volume 6, No. 132, Page 54, July 10, 1942.

One more the importance of ample air support for naval forces operating in narrow waters has been emphasized. So far as can be gathered from the various accounts that have been published of last month's convoy action in the Mediterranean, surface forces did not come into contact except for a brief period. Most of the damage inflicted on the enemy was by air attack. For the first time in the Mediterranean American aircraft took part in the operations.

On this occasion, to give supplies a better chance of getting through, two strongly escorted convoys sailed simultaneously, one from Gibraltar under Vice-Admiral A. T. B. Curteis, the other from Alexandria under Rear-Admiral Sir Philip Vian. The latter force, having passed supplies into Tobruk, was steering a course towards Malta when air reconnaissance reported an Italian force, including two battleships of the Littorio class, four cruisers and eight destroyers, at sea south of Taranto. During the night of June 14 and next morning attacks were made by Allied aircraft, including bombers manned by American Army personnel and British torpedo planes. Several bomb hits were made on the two battleships, causing fires. A torpedo hit may also have been scored on one of them. A heavy cruiser of 10,000 tons, belonging to the Trento class, was set on fire by bombs and ultimately sunk by torpedo from one of our submarines. At least one smaller cruiser and a destroyer were also damaged. As a result the enemy altered course to the northward and retreated to the Taranto naval base.

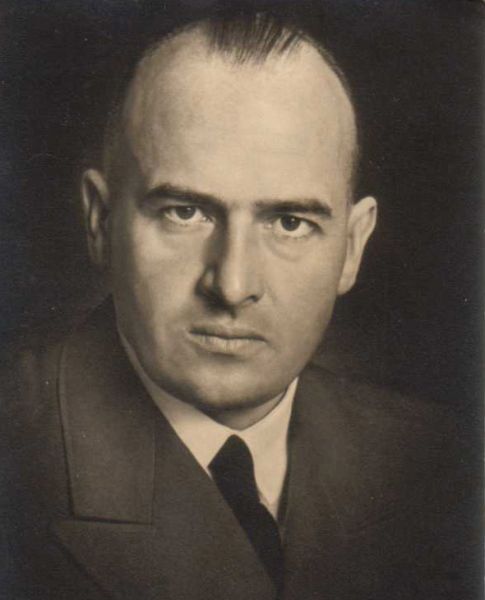

On the same morning another Italian force was driven off by British torpedo aircraft off the island of Pantelleria, between Sicily and Tunisia. It was composed, according to an Italian official statement, of the cruisers Eugenio di Savoia and Raimondo Montecuccoli, and the destroyers Ugolino Vivaldi, Lanzerotto Malocello, Ascari, Orione and Premuda, under the command of Rear-Admiral Alberto da Zara, aged 53. One of Admiral da Zara's cruisers was set on fire during the engagement, and a destroyer was almost certainly sunk.

Throughout the week-end, on June 13, 14 and 15, many bombing attacks were intercepted, heavy fighting taking place. On one occasion a raiding force of 40 Junkers 87s and Ju.88s, escorted by more than 20 Messerschmitt 109s, was intercepted. Undoubtedly considerable losses were inflicted on the Axis air forces in this action, 43 planes being certainly destroyed, and probably 50 per cent more. In attacks made on the eastern convoy the enemy lost at least 22 aircraft. (For a description of the air aspect of the battle see page 40).

It has been emphasized by the Admiralty that Axis claims to have sunk four British cruisers and to have damaged a battleship and an aircraft carrier are fantastic and without foundation.

Thought the difficult operation of escorting convoys through the danger zone between Italy and Tunisia and Libya was not accomplished without loss, the object of delivering supplies to the garrison of Malta and Tobruk was effected in spite of the enemy's efforts to intercept the convoys. Thus as much success as could be expected in such circumstances was gained by the Allied forces. Had the Italian squadrons stayed to fight it out, there is no doubt that the success would have been far more decisive; but for good reasons, based on sad experience in the past, the Italian Navy never risks encountering our fleet at sea if it can avoid it.

In all, the British losses amounted to one cruiser, four destroyers and two smaller vessels, besides 30 aircraft. At the lowest estimate, the enemy lost a heavy cruiser, two destroyers, a submarine and 65 aircraft, besides having one of their best battleships torpedoed and put out of action.

There are five Italian battleships in service. Two are modern ships of 35,000 tons, the Littorio and Vittorio Veneto; and the other three are rebuilt ships of 23,622 tons, the Giulio Cesare, Andrea Doria and Caio Duillo. A sixth ship, belonging to the latter type, was the Conte di Cavour, reduced to a wreck by British torpedo attack from the air at Taranto in November 1940; she is not believed to be fit for further service.

On June 12 the United States Navy Department revealed details of the operations in the Coral Sea during the first week in May, which for reasons of security could not be published earlier.

Though surface forces were never in contact, it is considered that the Japanese lost 15 warships, all from air attack. The United States force, which was under the command of Rear-Admiral Frank J. Fletcher, lost only three. The action began with an air attack on Japanese ships in the vicinity of Tulagi, in the Solomon Islands. In this affair 12 Japanese ships were sunk or badly damaged, and six aircraft destroyed. The Americans lost three planes. On May 7 an attack was made on the main enemy force in the Louisiade Islands, resulting in the sinking of the new 20,000 Japanese aircraft-carrier Ryukaku, which received ten torpedo and 15 bomb hits. Caught just as she was turning into the wind to launch her aircraft, she took most of them to the bottom with her. A heavy cruiser was also sunk.

Counter-attacks by enemy aircraft were beaten off, more than 25 Japanese aircraft being brought down as compared with six American. In the afternoon, however, the enemy located the U.S. naval oiler Neosho and an escorting destroyer, the Sims, of 1,570 tons, sinking the latter and badly damaging the former that she foundered some days later.

On May 8 a further attack was made on the Japanese force, a second 20,000-ton aircraft-carrier, the Syokaku, being bombed and torpedoed. When last seen she was badly on fire. A counter-attack was concentrated on the U.S. aircraft-carrier Lexington, of 33,000 tons, which was hit by two torpedoes and two bombs, this being the last incident of the action. Though the fires raging in the Lexington were extinguished, and she was able to proceed at a speed of 20 knots, a tremendous internal explosion occurred several hours later, due to ignition of petrol vapour from leaks caused by the torpedo damage. After five hours of vain endeavour she had to be abandoned, blew up and sank.

In the action off Midway Island between June 4 and 7 aircraft-carriers again played the principal part, though the surface ships do not appear to have come within 100 miles of each other. Full details have yet to be published, but Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief of the United States Pacific Fleet, considers that two Japanese aircraft-carriers, identified unofficially as the Akagi and Kaga, each of 26,900 tons, were sunk as well as a destroyer. One or two more aircraft-carriers, three battleships and four cruisers received damage of a more or less extensive nature. (See page 61).

On this occasion the only American warship lost was a destroyer, torpedoed by a Japanese submarine. Some damage was sustained by a U.S. aircraft-carrier. Apparently the enemy casualties were mainly due to air attack, though the destruction of one of the aircraft-carriers was caused by three torpedoes from an American submarine.

Following on the Coral Sea losses, this Japanese defeat off Midway seems likely to be the turning-point of the naval war in the Pacific. In tonnage the Japanese fleet has lost about 45 per cent of its aircraft-carriers, a type of war vessel of which the importance can hardly be exaggerated.

Previous and next article from The War at Sea

The War at Sea

After a period of comparative quiescence, following their repulse in the Coral Sea action, the Japanese resumed activity in the Indian Ocean and Pacific at the end of May. Their most important move

The War at Sea

WITH the rapid advance of General Rommel's forces over the Egyptian frontier and past Mersa Matruh, the idea seems to have arisen in many minds that our fleet in the Eastern Mediterranean would have n

Index

Previous article

The War in the Air

In the fast-moving panorama of the air war, some events appear to invest themselves with the significance of isolation. Dramatic as these happenings ofter are, it is a mistake to regard them as things

Next article

I Was There! - What the Americans Told Me About Midway

These first eye witness stories of the Japanese defeat in the sea and air battles off Midway Island on June 3 and 4 were told to Reuter's correspondent by American participants in the action. It wa