Views & Reviews

The Chetniks of Yugoslavia

By Hamilton Fyfe.

The War Illustrated, Volume 6, No. 146, Page 499, January 22, 1943.

When you read now and then about the guerrilla war that is being carried on against the Nazis in the mountains of Serbia, and about the leader of the brave men who are fighting for their country’s independence and freedom, how do you picture this General Mihailovich to yourself?

With some knowledge of Balkan comitadjis, as the bands of turbulent mountaineers who have disturbed the region called Macedonia for so many years are called, I supposed him to be a man of tough, even ruffianly appearance – not young by any means, full of courage, but not very brainy. I was surprised to discover from the photograph of him in George Sava’s new book, The Chetniks of Yugoslavia (Faber, 10s.), that he as a face in which intellect as well as character are plainly discernible. This is how the London doctor (born Russian, now British) who calls himself for literary purposes Sava, describes the General:

A man in the late forties, of medium height and with striking eyes of a bright mountain-flower blue, and fairish curly hair. But his physical details were dominated by his presence. It was that of the born natural leader. Here was a man, one said at once, in whom one could place one’s entire faith, a man to die for. Yet there was nothing aloof about him… He put no gull between himself and us, such as an officer puts between himself and his men and even more so between himself and irregulars.

"Irregulars" though they are, these Yugoslavs know more about the sort of warfare that is going on in the region between their country and Montenegro, Albania and Greece, than any of the scientifically-trained German staff officers. Mihailovich had a training of that kind himself. He was in the army, served as a lieutenant in 1914-15, then as military attaché in Sofia and Prague. He had a command in 1941, but found it impossible to stand up against the enemy’s tanks and artillery with the poor equipment he was given. When the order to capitulate reached him, he had only a few battalions of Chetniks left. With them he moved into the mountains, ignoring the instruction to surrender, resolved to "carry on the war to the victorious conclusion and show that Serbia still lives".

Now, who are the Chetniks? They do not seem to be a race or a tribe. The term is used apparently to describe people who live in a certain part of the wild country on the Yugoslav border. Anyway, they are showing the Germans what the spirit of Yugoslavia is.

Their task was to collect together the scattered fragments of the army which refused to surrender, so that they might reform to make a new fighting force in the heart of the land… From all parts peasants came to the centres of resistance, bringing with them old guns and hunting-rifles, some of the muzzle-loaders complete with ramrod and powder-horn. Trains of miles dragged small century-old cannon, for which no ammunition could be procured. And against these weapons the Germans used all the resources of a modern army. They bombed and machine-gunned from the air. Their heavy tanks lumbered about.

But it must have seemed to them that for every one Yugoslav they crushed, two more made their appearance. During one month the Chetniks killed 12,000 Nazis, blew up 200 bridges, set fire to between three and four hundred petrol, ammunition, and store dumps, wrecked seventeen trains. They made the Germans jumpy, never knowing where they would strike next or what they would do.

Their methods were ingenious. One was to make thermometers with a very powerful explosive in them, and put them up in railway stations, public buildings or hotels frequented by German officers. No one took much notice of them until they went off. The Italians were particularly scared. It was said they would not for months let thermometers by put into their mouths in hospitals for fear they might be blown up!

When an Alpine regiment, trained in the highlands of Bavaria, was sent against them, the Chetniks showed them they were up against men who knew every crag and cranny on the barren heights. They were decoyed up to a mountain from which there were only two ways down – one the road they used, which was promptly closed behind them, and a sheer abyss of 2,000 feet. None of that regiment escaped.

There is a rough humour about the Chetniks. They captured eighty Germans by derailing a train loaded with ammunition. What should be done with them? Mihailovich asked. "We won’t hang them for the crimes they have committed on our people. We must teach them a lesson. We’ve got to frighten these bullies. We’ll put their trousers down and write on their backsides, ‘Show yourselves to the garrison of Belgrade. The next we capture we shoot.’"

They actually did that, tattooing the message with an indelible vegetable dye, putting the prisoners into coffins, loading the coffins on wagons, and driving the wagons into the heart of the capita. They were taken to the doors of the German headquarters: there the drivers decamped. In a few minutes the men in the coffins began to wriggle, then to put their heads up. Their comrades came out and released them. "Fear struck deep into their hearts. Many of these soldiers, no more than boys, turned pale and began to cast hurried glances about them, while they fingered their triggers nervously."

With the Chetniks are a number of British soldiers who made their way into the mountains after the disastrous end of the campaign in Greece in the spring of 1941. They taught their hosts how to use anti-tank rifles and other modern weapons; and they repaired tanks captured from the enemy, which the Serbians had not been able to do anything with. Their chief difficulty was getting accustomed to the food and to the small amount of it. But in villages where there were pigs and poultry they managed to "initiate the Serbs into their favourite breakfast dish, eggs and bacon".

That the Germans would like very much to keep their grip, which is growing weaker, on Yugoslavia is obvious. It is a country of vast potential riches. It has, for instance, the largest deposits in Europe of bauxite, which is necessary to the making of aluminium for aircraft construction. It has zinc and iron ore, lead, silver and marble; immense forests, enormous numbers of pigs and sheep.

Little has been done to develop these possible sources of wealth. The great mass of the people are without any kind of formal education. Their rulers have been more anxious to make themselves prosperous than to bring prosperity to the nation. Large districts are inhabited by people who have scarcely advanced in the arts and ideas of civilization during the last two thousand years. The Nazis do not allow that they have "any value as human begins", they are "so much cattle, ripe for exploitation".

After the War some federation of the Balkans must be formed for mutual protection. So far the system there has been "all against all". I remember being one autumn in a little town near which are the frontiers of Bulgaria, Rumania and Yugoslavia. I made friends with a Russian who had been an admiral in the Tsar’s Navy and was now by an odd turn of fortune commanding a gang of desperadoes who carried had grenades in their pockets and lived on the country like bandits – though they didn’t like being called bandits. They called themselves patriots.

I have many amusing recollections of them. One is of a supper-party that admiral gave, at which performed an orchestra of three musicians looking, I thought rather nervous. When after supper the comitadjis began firing their revolvers at the ceiling and the pictures on the walls, I understood why. I got my feet up on the seat f my chair when the man next to me fired into the floor, and I left soon afterwards. But I was glad of the experience, for it showed me what sort of people prevented the Balkans from becoming civilized. Subjected to the discipline of an ordered, peaceful society, these desperadoes would have been fine fellows. Perhaps if Gen. Draza Mihailovich comes through and leads his countrymen in peace as boldly and cleverly as he is leading them in war, we may see such society.

Index

Previous article

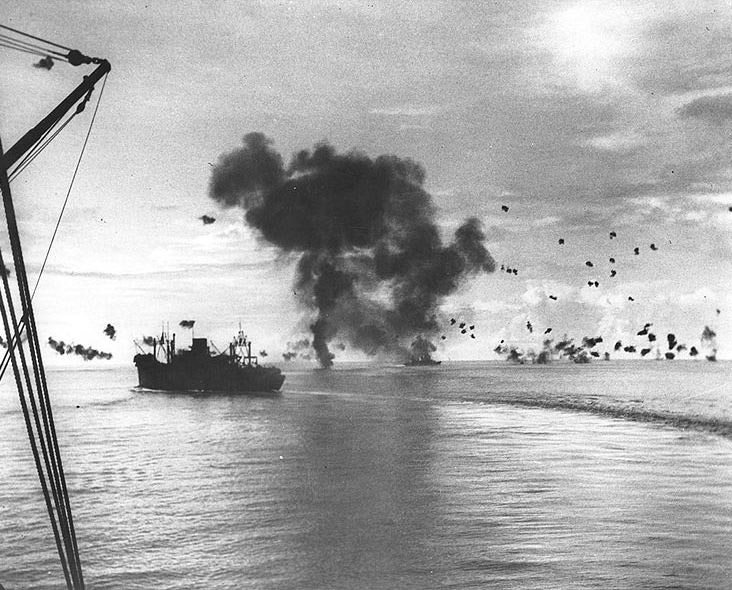

Fierce Battle off Guadalcanal

Fierce Battle off Guadalcanal. On Nov. 12, 1942 U.S. naval forces bombarded Japanese shore positions on this important island of the Solomons, and during these operations the enemy lost 30 out of 31

Next article

I Was There! - Our 80,000 Miles in the Triumphant Truant

Recently arrived at a base in Britain after an 80,000 mile cruise, lasting two and a half years, in the Mediterranean, Indian Ocean and Java Sea, H.M. Submarine Truant has to her credit the sinking or