The Truth About Lidice

By John Fortinbras.

The War Illustrated, Volume 10, No. 242, Page 355-356, September 27, 1946.

By John Fortinbras, who obtained from the Czech delegation at the Nuremberg trial information which enabled him to record the full account of this terrible Nazi crime of 1942.

Once a sizeable, peaceful Czech village in Bohemia, Lidice belongs now to history. It is not a village any more – nothing but a flat, sightless memorial to a nation's shame. Never, so long as written record endures, will the darkness associated with its name be forgotten. On May 26, 1942, the Deputy Reich Protector, S.S. Obergruppenfuehrer Reinhard Heydrich, "Butcher Heydrich", as he was more deservedly known because of his regime of murder, was waylaid by Czech patriots. Theirs was a long-premeditated plot to rid their country of this evil man. As they fired at him Heydrich slumped forward in his car, struck by a revolver bullet in the chest; a grenade splinter also hit him. Mortally wounded, he died eight days later.

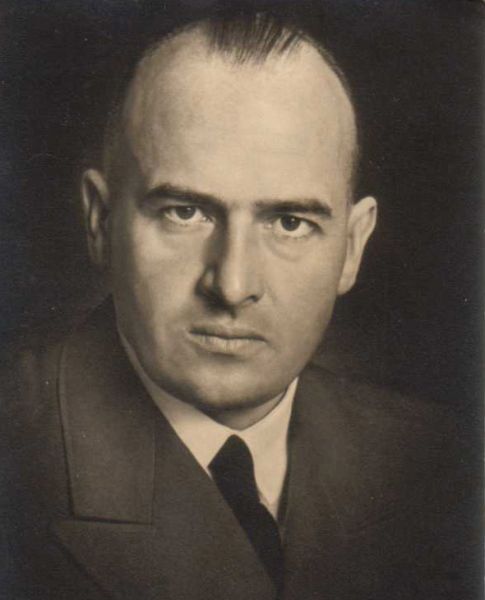

Immediately following this assassination of one of their Party leaders, the Nazis launched a great cry for vengeance. Hitler, in a personal telephone call to Dr. Karl Hermann Frank, State Secretary to the Reich, Protector of Bohemia and Moravia, demanded at once the execution of 30,000 to 40,000 Czech citizens; and since they were to be disposed of through the "Standgerichte", law courts only in name, Hitler's order was tantamount to condemning them to death without trial.

How Lidice Caught the Nazis' Eye

Frank, since executed by a Czech war crimes court, testified that he, by a personal interview with Hitler, had this order withdrawn. But other measures, scarcely less horrifying, were introduced and pursued with Nazi thoroughness. Ordinances were published condemning to death not simply the patriots responsible but all who might shelter them, might harbour knowledge of their whereabouts or hold any clue whatsoever tot their identity or existence. Moreover, the entire families of such "accomplices" would, it was ordered, suffer a like punishment. Immense rewards were offered to informers.

But, thanks to Czech loyalty and the common hatred of their oppressors, no trace of the perpetrators was disclosed; not the tiniest clue, though very many people, especially in Prague, knew their secrets.

Fanatically, the Gestapo hunted for evidence, finally for scapegoats. Then, fortuitously, its agents intercepted a postcard in the Czech civil post, in which the writer suggested that perhaps in Lidice was a man who could tell a thing or two about the Heydrich case. Not more than that. A mere "perhaps". And, as later evidence showed, this suggestion was utterly unfounded, a remark put down in innocence and without any malice. But Lidice, thus caught the Nazis' eye.

One further reason added to this unwelcome prominence. The Nazis, according to their secret lists of Czech resistance members, knew that three members of a family in Lidice had escaped to England, and were serving, in our country, with the Czech Armoured Brigade. It was enough. Through the direct of Dr. K. H. Frank a fearful retaliation was ordered. Lidice was to be razed to the ground and its male inhabitants exterminated. That was the order. And swiftly was it executed ruthlessly and in appalling manner.

On June 9, 1942, six days after Heydrich's death, the reprisal plan was launched. S.S. men, filling ten large Wehrmacht lorries, arrived from Slany. At once they threw a cordon round the village. All inhabitants had to stand fast in their homes. No one must leave the village. Peasants with work to do there were passed through the cordon, and their return prevented.

Rumours, terrible rumours, passed from mouth to mouth inside the village. They merged quickly enough into realities. A woman tried to break the cordon. As she ran, an S.S. man hit her with a bullet in her back. Some weeks later, during harvest time, neighbouring villagers found her body in a cornfield. A 12-year-old boy also bolted. He too was shot dead as he fled.

Then, with the cordon secure, and all means of communication with the outer world denied, the Gestapo acted. They locked the women and children in the village school. They locked and guarded the male inhabitants in the cellars, barns and stables of the Horak farm. They searched every house, but found not even a scrap of incriminating evidence. In the Horak farm, a remarkable atmosphere of spiritual calm prevailed. Each man, some of them boys, knew he was going to die. And perhaps not die easily. In their midst moved a patriarchal figure, the 73-year-old Priest Sternbeck. All night he prayed for the souls of these humble and innocent villagers. They knelt with him, a doomed defenceless company. Morning came – the morning of June 10, 1942 – the last day in the life of Lidice. A firing squad, 30 strong, of Ordnungspolizei reported from Prague at 03.30 hours. Shortly after it was daybreak they began their foul task. S.S. Hauptsturmfuehrer Weismann first addressed them. "It is the will of the Fuehrer which you are about to execute", he said. They were warned under peril of death not to disclose that they themselves had ever heard of the village. Among these executioners may have been some who felt a spark of pity, but they gave no sign of it.

In tens the men of the village were led out from the Horak farm to the garden behind the barn. Here, their executioners waited for them. The killings went on intermittently until 4 p.m. At one period Dr. K. H. Frank arrived in full uniform, just to see how smoothly his orders were being carried out. According to evidence given at his trial four years later, he expressed the desire that "corn should grow where Lidice stood".

Photographed Beside the Bodies

As the light was clear – it was a serene June afternoon and several Germans had cameras, the executioners let themselves be photographed in groups besides the bodies of their victims. Come, but not all, were proud to be snapped in these circumstances. From these prints, some of which have passed into the possession of the Czech Government, two facts emerge. One, the extreme youth of several members of the execution squad. One or two could not have been over 16 years. Secondly, the pictures testify to careful preliminary arrangements, such as the stacking of large piles of straw against the barn wall to prevent bullets rebounding or ricochetting.

Next day Jewish slave labourers from Terezin came to bury the massacred. They dug a large communal pit near the execution scene, piled the bodies into it, some indiscriminately, others head to toe, poured quicklime over them, and finally covered the pit with boarding. Altogether this grave, designed to by unknown and unrecorded, all Christian rites being deliberately denied it, received 172 men and boys aged 16 and upwards.

Those inhabitants with the seeming good luck to be working outside Lidice on these terrible days did not escape. From the collieries at Kladno, an adjacent mining village, the Gestapo seized another 19 male members of Lidice families, drove them to Prague, and there executed them. Seven Lidice women perished with them.

Germans Filmed the Obliteration

A fate different, though in some respect more horrible, befell the remaining women and children of Lidice. The 195 women and girls herded into the schoolroom were deported to Ravensbruck Concentration Camp, a Vernichtungslager or death camp. There, 42 of them died from ill treatment and misuse; seven others were gassed and three declared missing. Four of these women, being expectant mothers, were first sent to a maternity home at Prague. It is believed that their children were murdered. The mothers, later removed to Ravensbruck, never saw them after birth. Two or three other Lidice women bore children in Ravensbruck KL (Konzentrationlager). Those children, it is certain, were murdered almost immediately after their birth.

Then the children proper of Lidice were all torn from their mothers – 90 to go to Lodz in Poland, after which they were transferred to Gneisenau KL in Wartheland. Other Lidice children, the very youngest of those shut up in the schoolroom, were sent for special examination by "racial physicians" to the German children's hospital in Prague. Their blood was evidently deemed good, of "Herrenvolk" quality. They were then deported to Germany, renamed with German names. Only the merest handful of these children have been traced since the end of the war.

It was not enough, for Nazi conceptions of vengeance, to kill and scatter the people. The village itself had to be erased. Already, whilst the massacre was continuing, Lidice began burning, Systematically, beginning with the home of the family Hlim, situated on the road to Hestoun, the Nazis placed canisters of oil and other inflammable materials, straw in the case of farm-houses, inside shops and simple peasant dwellings, and fired them, until the whole main street was ablaze.

As Lidice blazed and smoked, a German film unit, commanded by Dr. Franz Treml, photographed each phase of the obliteration. I saw his film, a testament in itself of crime, at the Nuremberg Courthouse, when the Russian Prosecution presented it as evidence of Nazi mass destruction of villages. It is a vivid documentary, and in contrast to burning village shops, with black oil-smoke sprouting from their windows, crumbling and erupting walls, destroyed implements and dead animals one sees groups of smartly dressed S.S. officers, studying the ruins with their field glasses, and joking together, as the village collapses in smoke and flame.

Pitiful Field of Hidden Skulls

Still the destruction went on. On June 12, explosive charges were sunk beside the foundations of St. Martin's, the village's ancient little church. Once again the Gestapo drove in from Kladno to observe their policy of obliteration in action. Under their eyes the church was shattered. The whole village lay mute, shattered, a single heap of rubble. Todt labour squads, nearly all their personnel conscripted natives, carted away the rubble for road making. The village became a waste, a field of hidden skulls.

Although many other villages in Eastern Europe, including hundreds of Soviet villages, shared the scorched earth fate of Lidice, their inhabitants in some cases being submitted to worse penalties, there is only one Lidice, only one name in Europe to symbolize mass murder of an entire community.

Previous and next article from Great Stories of the War Retold

The Tragedy of H.M.S. Glorious

In view of the important role played by aircraft carriers in the Second Great War, it is a deplorable fact that, almost to the last, the Royal Navy found itself shorter of these ships than of those of

Cassino: Ypres of the Second Great War

By L. Marsland Gander, who as War Correspondent of The Daily Telegraph saw the capture of Monastery Hill and the town of Cassino in May 1944. The jagged, piled masonry of Cassino today poses one of

Index

Previous article

I Was There! - How I Said Good-bye to Bonaventure

Early in the morning of March 31, 1941, H.M.S. Bonaventure, accompanied by the destroyer Hereward, was escorting two troopships from Crete to Alexandria, when she received two torpedoes in the starboa

Next article

His Majesty's Ships - H.M.S. London

Motto: “Guide Us.” A Cruiser of 10,000 tons with a main armament of eight 8-inch guns, H.M.S. London was first commissioned at Portsmouth in 1929. For most of the ensuing ten years she was flag