Introduction

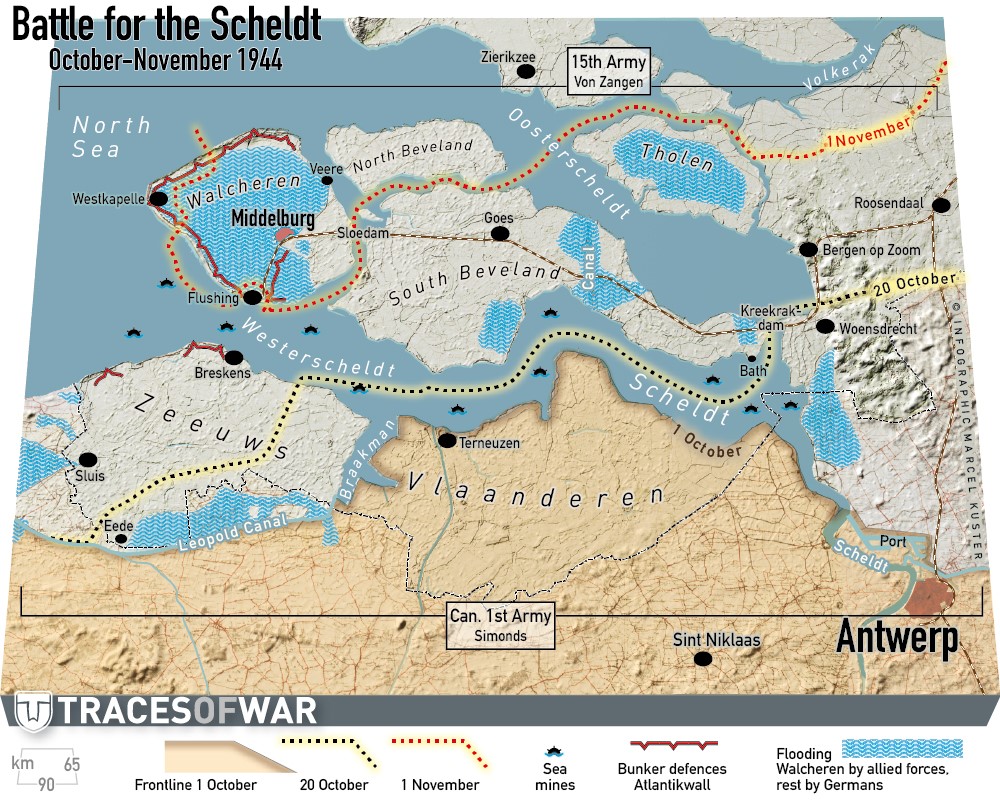

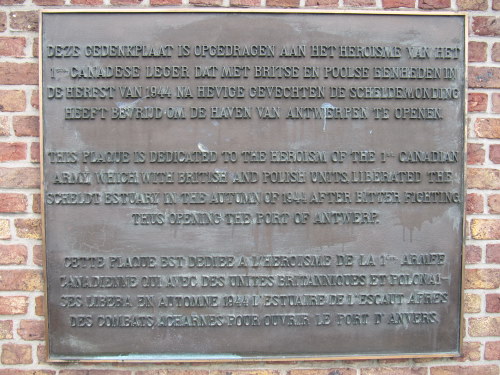

The developments on the Western Front, from the moment the allied troops crossed the river Seine by the end of August 1944, made the position of Antwerp more and more important. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the American commander of all allied troops in Western-Europe already saw in an early stage that future operations, deep into Germany, only were possible if the provisioning and supply could take place through a deep water harbor close to the frontline. In August 1944, the allies did not comply with that condition. The advance that followed from the river Seine had to comply with this demand and one of the primary targets of the allies was the liberation of Antwerp.

Aligator and Terrepin amphibious vehicles near the Scheldt, close to Terneuzen, 13 October 1944. Source: National Archives of Canada

Already on September 4th, 1944, this goal was reached and the clearing of the city and the docks took only a few days. Target achieved? General Brian Horrocks, commander of the British 30th Army Corps and responsible for the attack force on Antwerp, has written after the war that he could be blamed for the conquest of Antwerp on September 4th to be a "serious mistake": he should have passed the harbor city at his left flank and before anything else, he should have had the 11th Armoured Division advancing via a bridgehead over the Albert Canal to Woensdrecht (Noord-Brabant) and the isthmus of Zuid-Beveland (Zeeland), in order to prevent the retreating German 15th Army [15. Heresabteilung] from crossing the river Scheldt. He furthermore wrote: "It never occurred to me that the river Scheldt would be flooded with mines and that we could not use Antwerp harbor if not first of all the mines would have been swept and we had driven the Germans away from both banks." His attention and the attention of his immediate chief, Field Marshall Bernard Montgomery, at that moment of time were completely focused on taking Arnhem and crossing the river Rhine. There it was, according to the generals, that the decisive battle had to be won, in order to advance thereafter deeply into Germany and thus to force a quick ending of the war in Europe.

Unfortunately the battle for Arnhem (17 – 25 September) was lost and to blame for this loss was, ironically, also the lack of supplies. Montgomery, responsible for the whole northern sector of the front, had to admit that after the misfortune of loosing the battle for Arnhem, the opening of the Scheldt estuary became now priority number one.

The German General Staff also realized that the free entrance to Antwerp was of crucial importance to the allies. After General Gustav-Adolf von Zangen with his 15th army had been able to escape from being surrounded by the allied forces at Calais, the majority of his troops (about 90,000 strong) had been able to arrive at and cross the Westerscheldt and had therefore been in the position to establish forceful defenses around the river mouth. A part of Zeeuws-Vlaanderen became inundated and the German occupying forces could wait patiently for things that were to happen.

The Battle for the Scheldt could commence.

Retrospective view: the allied advance

The Canadians

The Canadian 1st Army, commanded by General Harry Crerar, crossed the river Seine at Rouen on 29 August and was responsible for the advancing along the coast of the English Channel. The troops were required to demolish the V1 bases and to liberate various ports. Not an easy task as Adolf Hitler had ordered that all ports had to be considered to be a fortification [Festung]. That comprised that the city had to be defended at all cost, also after being surrounded. Withdrawal was not allowed. The Canadians advanced along the coast and left troops behind to surround and to ultimately liberate the fortressed cities and their ports.

To begin with, the Canadian 1st Army started its advance successfully. In the early morning hours of September 1st the Canadians entered Dieppe. Between a cordon of people on both sides of the road, welcoming their liberators with flowers and who climbed on the trucks and carriers of the liberators to participate in the liberation, they tried to carry out their duties in an orderly manner. The Germans had, contrary to all orders, chosen to escape. And for the Canadians the liberation had sentimental value because of the losses among the Canadian troops during the Raid on Dieppe in August 1942. Within the perilous logistic circumstances of that moment the conquest of Dieppe meant a small relieve when on August 6th the harbor facilities were restored.

Oostende was liberated on September 8th but the harbor had been completely destroyed. Ships could only enter the harbor from 26 September without the risks of mines and other (underwater) obstacles. The siege of Boulogne (Operation Welhit) lasted from 6 to 22 September and the siege of Calais (Operation Undergo) from 6 to 30 September 1944. All these activities required an important quantity of men who could therefore not be deployed to fight at the front near Antwerp.

The British

The British 2nd Army under command of Lieutenant General Miles Dempsey, crossed the river Seine at Louviers on 25 August and at Vernon on 27 August 1944 and started to march northwards to drive the German troops through North France and Belgium at a maniacal speed. They advanced more to the east through the country side, parallel to the Canadians, via Amiens and Lille and thereafter partly via Gant to Antwerp and partly via Doornik and Brussels to Antwerp.

The British 2nd Army was even faster than the Canadians. On August 31st Amiens was liberated (after the resistance fighters had conquered three bridges across the river Somme) and Doornik (Tournai) and Brussels fell in allied hands on the 3rd of September. On 4 September the first British scouts reached the outskirts of Antwerp. With the help of the local resistance movement in Belgium, the city including the complete harbor works was liberated up to the Albert Canal. The Germans had left the town. Also the northern suburbs Ekeren and Merksem were left but the British omitted to continue their advance northwards and the following day the Germans returned to Merksem in order to establish defenses.

The Polish 1st Armoured Division proceeded into Belgium on September 6th without encountering resistance of any importance and on the same day the Canadian 4th Armoured Division continued to Bruges. Both units encountered heavy resistance at the Canal Bruges – Gant, so a quick crossing became impossible. With their backs towards the river Scheldt the German troops of the 15th Army fought grimly for control over the water way into Antwerp and to save their own skin.

Yet the allied forces succeeded in the course of September to cross this canal and to advance further, but a little more to the north they were halted completely. There the parallel running draining canals [Afleidingskanalen] of the river Leie and of the Leopold Canal formed a perfect defense line for the Germans and an insurmountable obstruction for the allies. Especially since still a large quantity of their troops were occupied forcing the German defenses of a number of ports along the English Channel to surrender.

The frontline in Zeeuws-Vlaanderen now ran south of Zeebrugge along the draining canals to the Westerscheldt at the inlet Braakman (which has today become a polder and dried up) , from there along the (left) bank of the river Scheldt up to Antwerp and further on along the Albert Canal towards the east.

Definitielijst

- Raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Planning

On September 5th 1944 it was decided to commit the 30th Army Corps (one of the two army corpses of the British 2nd Army) at Arnhem to Operation Market Garden. The occupation of Antwerp was therefore transferred to the 12th Army Corps. After the failure of Market Garden plans were drawn up to liberate the mouth of the river Scheldt. With reference to a directive of the 27th September issued by Bernard Montgomery it was decided to engage the enemy in a combined way:

- An attack to the north from Antwerp in the direction of Bergen op Zoom (Operation Aintree) on the way to Woensdrecht bending in the westerly direction to Zuid Beveland (Operations Vitality I and Vitality II), in order to commence the attack on Walcheren (Operations Infatuate I and Infatuate II).

- The conquest of Noord-Brabant by an attack in westerly direction from the salient near Arnhem (left over from the approach to Operation Market Garden).

- The conquering of Zeeuws-Vlaanderen by a combined attack from Terneuzen and across the Leopold Canal near Eede (Operation Switchback).

Please note: the conquest of Noord-Brabant will not be covered in this article because it did not have any immediate impact on the Battle for the river Scheldt.

The British 1st Army Corps under Lieutenant-General John Crocker was ordered to support the British 2nd Army and to proceed in the direction of Breda and Roosendaal covering the flank and the rearguard of the Canadian advance towards the connecting dam between Zuid-Beveland and the mainland (the Kreekrakdam). The 1st Army Corps was composed of the Polish 1st Armoured Division, the British 49th (West Riding) Division, the American 104th Infantry Division and (from 17 October) the Canadian 4th Armored Division.

The Canadian 2nd Army Corps under Lieutenant-General Charles Foulkes was charged with the task to clear the area of the river Scheldt. He received therefore the following units: the British 52nd (Lowland) Division, the Canadian 2nd Infantry Division, the Canadian 3rd Infantry Division and the 4th Special Service brigade.

The allies had to face a strong German defense. In the area of the Westerscheldt the German 15th Army (under General Von Zangen) consisting of the 64th Infantry Division (under General-Major Knut Eberding) was positioned in Zeeuws-Vlaanderen, the 70th Infantry Division (under Lieutenant-General Wilhelm Daser) on Walcheren and Zuid-Beveland and the 719th Division stayed north of Antwerp. And also the Germans had formed the so-called Gruppe Chill (this was an army corps built up from the remnants of defeated divisions) under command of Lieutenant-General Kurt Chill, which was held in reserve.

Definitielijst

- brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

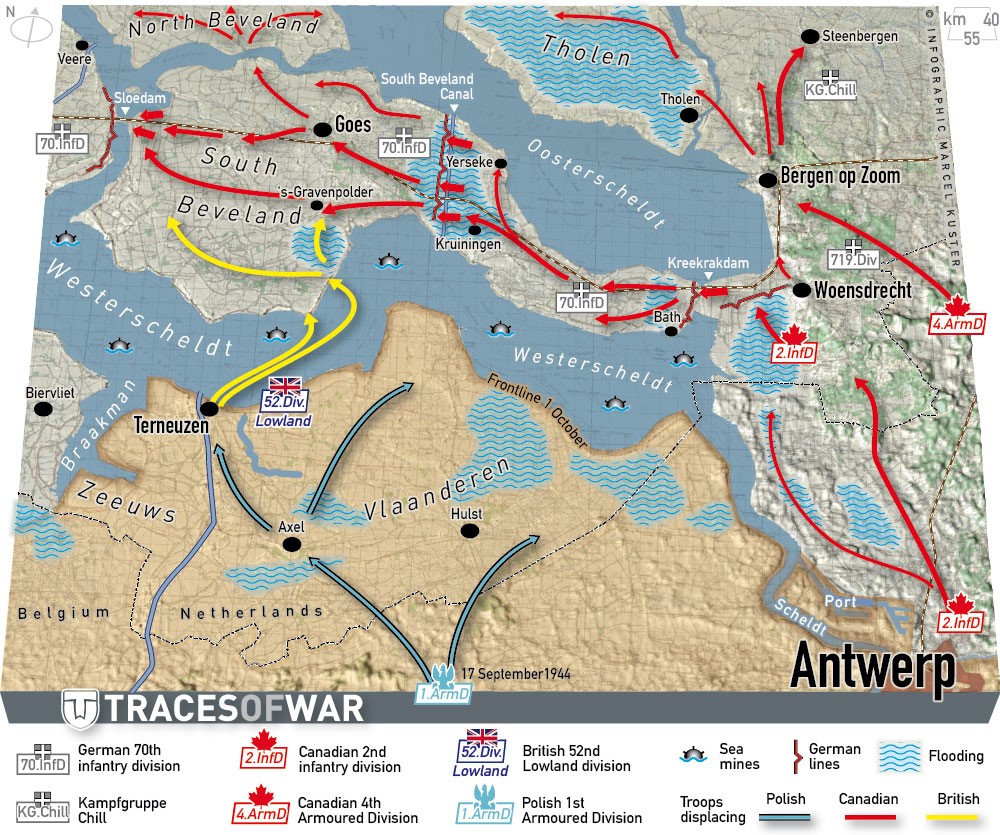

Via Zuid-Beveland to Walcheren

The Canadian 2nd Division began its advance on October 2. Starting from Antwerp they marched up to the Kreekdam (which is a narrow strip of land between Noord-Brabant and Zuid-Beveland). The infantry in the beginning made good progress, conquered that day Lochtenberg and Brasschaat on October 3. Putte, on the border between Belgium and The Netherlands was liberated on 5 October and the Canadians were at 5 kilometers distance from Woensdrecht on the 6th of October. The polder surroundings of Woensdrecht were inundated and Hoogerheide (at 1 kilometer from Woensdrecht) was captured after very heavy fighting by the Calgary Highlanders, but further progress was blocked. Air reconnaissance reported large numbers of German tanks and guns in the woods south of Bergen op Zoom. Captured Germans appeared to be paratroopers.

The conclusion was simple: the Germans had applied their reserves and Gruppe Chill had been directed southwestwards and participated in this battle. This army group had been ordered to hold the Kreekrakdam in order to keep the connection with the 15th Army. The fighting at Woensdrecht was intense and the losses counted high on both sides. An attack which was carried out on October 13th by the Canadian Black Watch (part of the Canadian 2nd Infantry Division) took 145 lost officers and men (56 died).

The Canadian 4th Armoured Division was part of Operation Suitcase, launched to put more pressure on the clearing of the Scheldt, with the advance target being Bergen op Zoom. The result of this operation was that the German Army Command recognized the danger Kampfgruppe Chill would be cut off. Chill was ordered to withdraw from Woensdrecht and Hoogerheide towards Bergen op Zoom. Because of this Woensdrecht could eventually be taken by actions of the 5th and 6th Canadian Infantry Brigades. Although the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry and the Essex Scottish Regiment (both of the 4th Canadian Infantry Brigade) also fought in Woensdrecht, they were not decisive.

By the liberation of Woensdrecht the Germans in Zuid-Beveland and Walcheren were cut off on the east side.

Over a week later the attack on Zuid-Beveland had commenced. Here a two pronged approach was used:

- Operation Vitality I regarded a direct attack on the Kreekrakdam, carried out by the Canadian 2nd Division

- Vitality II, a landing with amphibian carriers by the e 52nd (Lowland) Division, under command of the Canadian First Army, on the south east bank of Zuid-Beveland near Baarland.

The Germans had manned a line of fortifications at the entry of the Kreekrakdam and applied inundations at Rilland and along the South Beveland Canal. That canal was the main defense position.

On 24 October at 04:30 the attack started after the usual artillery barrages on the Kreekrakdam. The Air Force could not provide support because of a low cloud base and rain. The Canadian 4th Brigade (part of the 2nd Division) succeeded quickly in forcing a break through and supported by tanks they advanced across the Kreekrakdam. On the dam itself the tanks were sitting ducks for the German anti-tank weapons and many Shermans were destroyed. On the dyke many barricades were built, which obstructed the Canadian progress. It transpired very soon however that the infantry would have to pull the conks out of the fire and that the tanks could only be used later on. The next day the village Rilland-Bath could be liberated, also assisted by an air attack by Typhoons (a British fighter bomber armed with rockets). The spearhead then arrived at Krabbendijke and was later on replaced by the Canadian 6th brigade.

The Scottish 52nd Lowland Division had been committed to carry out the amphibian landings at the south bank of Zuid-Beveland (Vitality II) . A fleet of 25 LCAs (Landing Craft Assault – known from the Normandy landings), 176 Buffaloes (amphibian carriers on tracks) manned by the 5th Assault Regiment and the 11th Royal Tank Regiment and 27 Terrapins (amphibian trucks on wheels) were applied to ferry the 156th Brigade (of the 52nd Lowland Division). During the night of 25 to 26 October the crossing of the Scheldt was made from Terneuzen. Towards 05:00 the first troops landed ashore under cover from artillery gun fire. The German resistance was weak. The steep slope of the sea dyke appeared to be the biggest hurdle and had to be partly blown up in order to enable the amphibian trucks to drive ashore. After two hours all men were on land and dispersed in skirmishing order over the peninsula. The Buffaloes were used to evacuate part of the civilian population.

On 28 October the troops that crossed the Kreekrakdam built a pontoon bridge across the South Beveland Canal, crossed it and a day later the two parts of the attacking forces made contact at ‘s Gravenpolder. Goes and the western part of Zuid-Beveland were then liberated without major difficulties. The 450 men strong occupying forces surrendered without any battle worth mentioning. And on October 30 Zuid-Beveland was in allied hands, after the German General Wilhelm Daser had ordered the remainder of the German troops to withdraw to Walcheren.

Definitielijst

- Brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- Kampfgruppe

- Temporary military formation in the German army, composed of various units such as armoured division, infantry, artillery, anti-tank units and sometimes engineers, with a special assignment on the battlefield. These Kampfgruppen were usually named after the commander.

- paratroopers

- Airborne Division. Military specialized in parachute landings.

- Regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

The Battle in Zeeuws-Vlaanderen

In Zeeuws-Vlaanderen the battle started with the attacks over the Leopold Canal. The Germans held strong fortifications in the partly inundated polders of western Zeeuws-Vlaanderen.

On 6 October, 1944, at 05:30 the Canadian 7th Infantry Brigade (which had just arrived from walking 150 kilometers as they had been engaged in the fighting for Calais, which only fell on the 1st of October) crossed the Leopold Canal at Stroobrugge. This attack was carried out under cover of 27 Wasps (a Bren gun carrier equipped with a flamethrower). A little more to the west, at Moerhuizen, another Company crossed the canal, originally without the Germans firing a single shot. Both groups established a bridgehead but could not spread out because of heavy return fire by the Germans after they had recovered from their first fright.

On October 9th after heavy fighting both the bridgeheads were assembled and on 13 October the Royal Canadian Engineers built a bridge across the canal and the Canadians gained firm ground at Eede. The day after the 4th Armoured Brigade could cross with their tanks and support the infantry to disperse the Germans. Two days after the start of the attack across the Leopold Canal the 9th Infantry Brigade attacked near the Braakman (today a polder but at that time an inlet of the Scheldt of a few kilometers wide, that stretched west from Terneuzen almost to the Belgium border). The British 79th Armoured Division had supplied the Buffaloes and Terrapins to cross the Braakman. After crossing the 9 kilometers of water they surprised the German defenses completely. The Canadians only received counter firing when daylight broke and after a strong bridgehead had been established.

But then the Germans commenced seriously. From the other side of the Scheldt at Flushing and from Breskens in the west, the attackers met with heavy artillery fire (from the coastal batteries ed.) and the Canadians had to lay a smoke screen from Terneuzen up to the frontline in order to hide the transport movements from the Germans.

In the meantime the Germans had ferried two companies of the 70th Division as reinforcements from Walcheren to Zeeuws-Vlaanderen across the Westerscheldt. On 14 October units of the 4th Armoured Division made contact with troops at the Braakman frontline. This improved the situation because supplies could now be carried from the south instead of across the water of the Braakman.

On October the 18th the Scottish Lowland Division, under the command of General major Edmund Hakewill Smith, took over from the Canadian 7th Brigade. The Lowland Division was a Territorial Division from South Scotland and excellently trained to carry out various tasks. They commenced the battle full of dash and liberated Aardenburg on 19 October. The Germans had withdrawn to defenses on the line Breskens via Schoondijke to Sluis.

With heavy artillery and with air support Breskens was attacked on 21 October. In the afternoon the small town was liberated but the old fortress Frederik Hendrik was still firmly in German hands. Only after intense fighting the occupation of the fort, 23 men, were forced to surrender on October 25th. Already on the 24th Schoondijke was captured and on October the 29th Cadzand fell in allied hands. General Knut Eberding and the remnants of the German 64th Division were made prisoner during the first days of November.

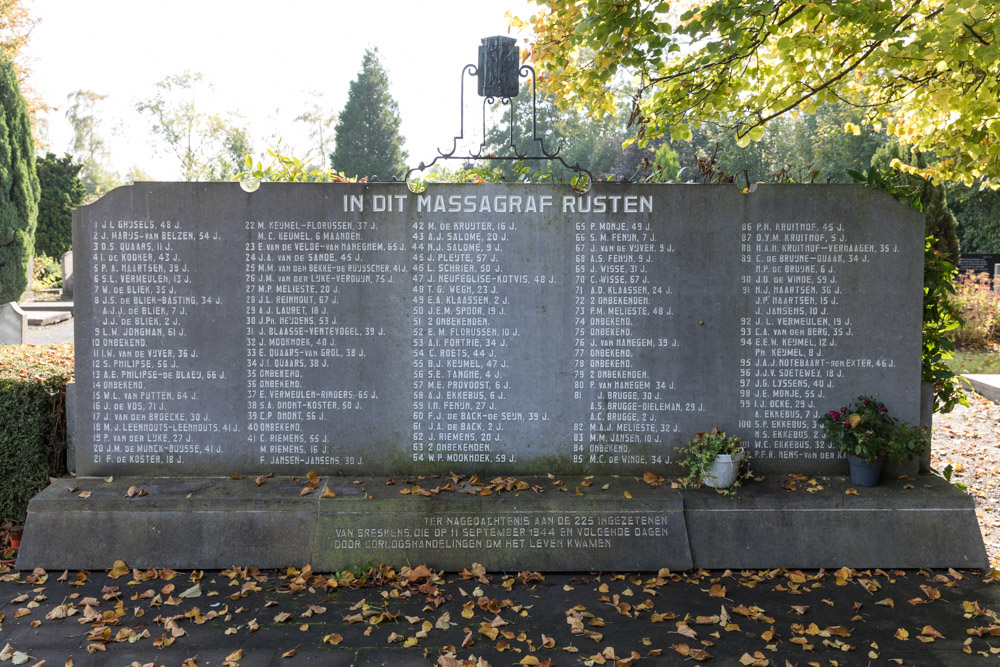

Operation Switchback was considered to be completed on the 3rd of November. 12,707 German military were made prisoner of war (POW). Over 800 Canadians and 788 Germans had been killed. The population of Zeeuws-Vlaanderen paid a heavy toll: 581 inhabitants were killed, 2,047 houses were totally destroyed and 1,021 heavily damaged.

Definitielijst

- Brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- POW

- Prisoner of War.

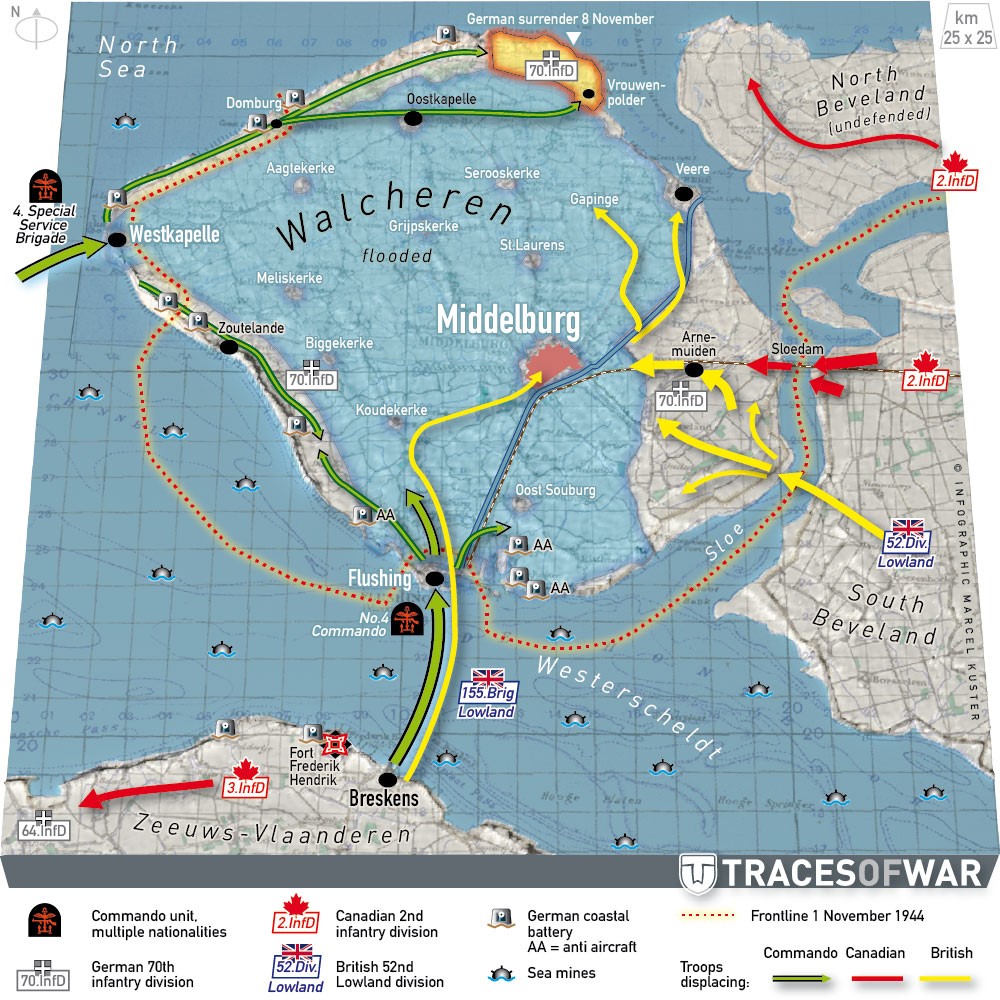

The Battle for Walcheren

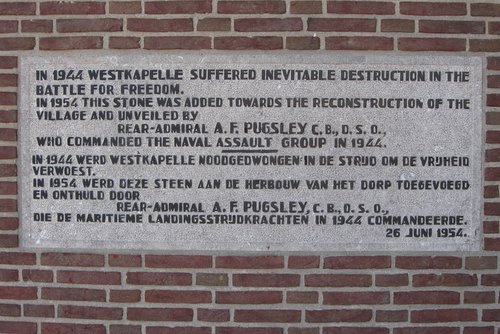

On this peninsula the Germans had at their disposal a number of artillery batteries, concrete bunkers with machine gun positions and other fortifications (part of the Atlantikwall ed.). The batteries were manned by the navy and were targeted towards the sea. In order to harass the Germans as hard as possible, the allied forces decided to inundate Walcheren (which is mainly below sea level ed.) before commencing the attack. By means of aerial leaflets the civilian population was warned for the dangers that were about to happen. Early in the afternoon of 3 October, 1944, 247 Lancaster and Mosquito bombers of the RAF attacked the dyke in front of Westkapelle. At this bombardment 120 yards of the dyke was destroyed and tens of civilians found their dead as yet. 46 Inhabitants of Westkapelle perished when the mill in which they had been looking for refuge, was destroyed by a direct hit. (The exit was blocked and the mill burned down to the ground. ed.)

As the flooding spread slower than expected over the peninsula, also the dykes at Flushing and at Veere were bombed. Because of the inundation the Germans were forced to withdraw to the highest areas on Walcheren. On the dykes and in the dunes that remained dry, the heaviest fortressed batteries remained active as the allied air forces had not been able to silence them with 8 to 9,000 tons of bombs in about 650 missions.

The attack on Walcheren

Involved in these actions were troops of British, Canadian, French, Dutch, Belgian and Norwegian nationality.

- On the east side the Sloedam, the connection between Zuid-Beveland and Walcheren had to be stormed. Units from the Canadian 2nd Infantry Division and in a later stage, the British 52nd Lowland Division, reinforced with commando troops from the 4th Special Services Brigade, were called upon to perform this attack.

- In Flushing, Operation Infatuate I, an amphibian landing would be carried out by the 4th Commando Batallion. Incorporated in this Batallion were 2 French "Troops" (=halve Companies) and eleven Dutch soldiers. An artillery barrage from Zeeuws-Vlaanderen (left bank of the Westerscheldt ed.) and an airraid would preclude this invasion. After the Commando Batallion, troops of the 155th Brigade, 52nd Division, were to be put ashore.

- Westkapelle, Operation Infatuate II, was the target of the remaining units of the 4th Special Services Brigade the Royal marine’s Commando 41, 47 and 48. These were reinforced with a Belgian and a Norwegian "Troop" and with 14 Dutch soldiers of 10th Commando. The British 79th Division took care of supplying the special (amphibian) carriers in order to make the landings possible. Also here the attack was preceded by artillery and air bombardments.

The Sloedam

The Sloedam was extremely hard to tackle. It consisted of a bare dyke of more than a kilometer of length. In those days on both sides of the dyke there were only tidal mud flats. The Germans were positioned in concrete bunkers and pillboxes and were dug in with tanks and anti-tank guns along the railway line. On October 31 the Black Watch of Canada started the assault and the soldiers advanced under heavy firing by the Germans. They proceeded up to 70 yards from the Walcheren side and then had to retreat. In the evening another Batallion, the Calgary Highlanders gave it a try. Also in vain. The next morning the Canadians tried again, this time with artillery support. They succeeded and set foot on Walcheren, but a nightly counter attack from the Germans pushed them back.

Finally the last Canadian Batallion achieved to penetrate into Walcheren and set up a modest bridgehead. Thereafter the British 157th Brigade took over and had to suffer a German counter attack on 2 November. But then help from an unexpected source announced itself: a member of the local resistance movement, Mr. Kloosterman from Nisse knew about a way to cross the Sloe south of the Sloedam. After reconnaissance had been carried out and mines had been cleared, during the night of 2 to 3 November a crossing was made with the help of storm boats and by wading through the cold but shallow water. In this way the 156th Brigade succeeded to enter the Bijleveld polder surprising the Germans completely. On 4 November these troops made contact with the 157th Brigade at the bridgehead at the Sloedam and the worst was over. In the evening a bridgehead of 4 x 2 kilometers was established and the march for Middelburg could commence. The German Commander, General Daser, surrendered the city without resistance and it could therefore be liberated without too many casualties.

Flushing

Right after the Black Watch had taken the Sloedam, the assault-fleet gathered for the amphibious landing at Flushing [Vlissingen]. Artillery, assembled around Breskens started to fire before the landings and bombarded the German positions around the town. In the night from 31 October to 1 November the invasion took place at the so called Slijkhaventje (= little mud harbor, ed.) which had received the code name "Uncle Beach". The storming by the commando troops was effective and within five minutes a 7,5cm gun was captured. Around 06:30 all 550 men of the 4th Commando had been put ashore. In Flushing intensive street fighting broke loose when they tried to reach their targets in the city. A short time afterwards the 4th Batallion, the King’s Own Scottish Borderers, and other units of the 155th Brigade had landed at cost of heavy losses. After dawn, the situation at Uncle Beach became hellish. The Germans incessantly shelled the area with their artillery. Also the Dutch resistance actively participated in the battle and succeeded in capturing the paper orders to destroy the shipbuilding yard De Schelde. By the interception of these plans, the ship yard escaped that fate.

On 2 November the Germans concentrated their defensive actions on the boulevard with its command post in a large concrete blockhouse, south west of the city. After an attack by fighter bombers, armed with rockets, the commando troops succeeded in capturing the bunker. On November 3rd, the town was taken. The Royal Scots, the last unit to land, stormed the Hotel Brittannia at Boulevard Evertsen which had been reshaped into a fortress. Here the German Garrison Commander, Oberst Reinhardt, had established his headquarters. Only after hours of resistance Reinhardt gave up and the city was liberated.

Westkapelle

During the same night of 31 October to 1 November, 1944, at 03:15 the fleet sailed from Oostende for the amphibious landings at Westkapelle. Also here, air support could not be provided because of the bad weather circumstances. And the ships’ artillery had to perform without air observation. When the lighthouse of Westkapelle was spotted, the ships maneuvered into their positions: the LCAs assembled for their attack and the warships, amongst which the British battleship Warspite and two gun boats, prepared for the coastal shelling. As soon as those ships opened fire, the German coastal batteries answered immediately. Because the warships attracted the artillery fire in this way, the landing crafts could reach the beaches relatively unscathed. Around 10:00 the LCAs lowered their ramps and the Buffaloes were launched and sailed through the gaping opening in the dyke and into Walcheren. Shortly after midday, the battery on the north part of the dyke (W15) was captured and Westkapelle liberated.

The south part of the dyke was also heavily defended by the Germans, but the battery at this side ran out of ammunition, which was a result of the inundation of Walcheren which had caused interruptions in the supply of stores and ammo for the battery. Thereafter the crew was quickly defeated in a short battle with light arms and hand guns. And the allies had established a firm bridgehead.

From this bridgehead 41 Commando marched north and captured Domburg on the same day. 48 Commando, on the southerly dyke, advanced in the morning of 2 November, with the Dutch soldiers in the spearhead, and they had to fight a fierce battle at Dishoek. The German battery (W11) that had been established here, had to be eliminated because it hindered the supply chain through Westkapelle. After a long and costly battle the commando troops succeeded to enter the battery in the evening and after a nightly struggle the battery was captured during the morning hours. The remaining batteries appeared to give less resistance and in the course of the evening the hole in the dyke near Flushing was reached. 41 Commando which marched north, became stuck after the liberation of Domburg. Only after four tanks had delivered the required firepower, battery W18 could be attacked, right below Oostkapelle. Three days the battle lasted here as the Germans had installed strong defenses in the woods, protected by minefields. On 6 November the enemy laid down their weapons and on November 8th the last resistance on the island was broken.

Definitielijst

- Batallion

- Part of a regiment composed of several companies. In theory a batallion consists of 500-1,000 men.

- battery

- Unit of the artillery operating a number of guns. In size comparable to a company. In various countries the staff unit with the artillery is also called a battery. Batteries can be independent units and can be assigned to other units, for example toa regiment or a division, or be part of a larger artillery formation which is usually a battalion. In the Netherlands an artillery battalion is designated as “afdeling”.

- battleship

- Heavily armoured warship with very heavy artillery.

- Brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- commando troops

- Special forces, deployed especially for missions behind enemy lines such as sabotage and reconnaissance.

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- inundation

- “Latin: No bottom”. The deliberate flooding of land with the aim of stopping or hindering the advance of the enemy into a certain area.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- machine gun

- Machine gun, an automatic heavy quick firearm.

- RAF

- Royal Air Force. British air force

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- shelling

- Indication for shooting targets with grenades. Both from artillery and armoured artillery.

Afterword

Between 1 October and 8 November the Canadian 1st Army lost 703 officers and 12.700 men, killed, wounded or missed in action. Of those 305 officers and 6,012 men were of Canadian descent. In total 41,043 Germans were made prisoner of war.

With hindsight General Dwight Eisenhower should not have succumbed to the plans of Bernard Montgomery and he should have insisted on the priority to liberate the mouth of the river Scheldt over the battle for Arnhem. The heavy fighting that was required for capturing the river mouth and the harbor entrance and to clear the river Scheldt from the mines, almost cost three months. In this period, during which the harbor of Antwerp could not be utilized, the provisioning of the troops at the frontlines was stagnant which hindered their progress. This provided the Germans with the opportunity to launch a serious offensive in the Ardennes and to reinforce their lines along the river Rhine. Montgomery has admitted afterwards that he has judged the situation incorrectly.

During the larger part of the month hard work was performed in order to free the harbor of mines and on 28 November the first convoy of Liberty ships was welcomed with some pomp. On the 1st of December 1944, 10.000 tons of goods could be discharged per day in Antwerp harbor and it would become an important logistical part of the war effort. The sacrifices had not been in vain.

Definitielijst

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

Information

- Translated by:

- Fred Bolle

- Published on:

- 11-01-2012

- Last edit on:

- 30-09-2024

- Feedback?

- Send it!