Prologue

According to history, Operation Market Garden should have been the operation that was to put an end to World War Two in Europe before the end of 1944. Up until today, this operation still triggers discussions about the goals, the set up and the result. This often appears to make whatever was decided and has happened at the time disappear into the background. It appears that in particular questions of guilt and what in fact should have been done have gained the upper hand in history.

Paratroops of 1st Airborne Division being dropped during Market Garden. Source: National Archives and Record Administration

Following the Battle of Normandy it seemed like the German defense had become confused. It appeared the German army had been defeated and towards September, almost all of France and Belgium had been liberated. It wasn't the German defense however, which prevented the Allies from taking advantage of this situation quicker. The real cause were the Allied supply lines becoming too long to supply all troops sufficiently. In order to solve tis, more ports were urgently needed. Although on September 4 the port city of Antwerp[1] had fallen into British hands virtually undamaged, the supply line through the River Scheldt firmly remained in German hands.

Right at that moment, the Allied supply lines couldn’t handle it anymore and the British advance to the north came to a halt, allowing German Heeresgruppe B, commanded by Generalfeldmarschall Walter Model defending this area, to regroup. When XXX Corps, commanded by Lieutenant-general Brian Horrocks leading the attack to the north, had been sufficiently supplied on September 6 to resume the advance, it was halted again a few miles from the Dutch border. At the Scheldt-Meuse Canal the Germans had established a well-organized defense. They had managed to extract 15. Armee, commanded by General der Infanterie Gustav-Adolf von Zangen from its precarious position in northwestern Belgium across the Scheldt.

As the front on the Scheldt-Meuse Canal was in danger of bogging down, the Allied commanders were compelled to switch tactics. Simultaneously supporting the advance of the Americans in northeastern France and the British-Canadian advance in northwestern France and Belgium was no option from a logistical point of view. In the ensuing discussion, Field marshal Bernhard Montgomery tried to solve the issue by proposing an audacious plan, Operation Comet. This plan entailed an air drop by the British 1st Airborne Division commanded by Major-general Robert E. Urquhart in the Netherlands. The operation was intended to capture the most important bridges across the rivers to allow the advance by 2nd British Army commanded by Lieutenant-general Miles Christopher Dempsey via the route paved by the airborne troops. General Dwight Eisenhower considered the plan too risky and rejected it, hence Montgomery adapted his plan. He proposed a ground attack by 2nd British Army with XXX Corps leading the way and the deployment of no less than three airborne divisions. This was how Operation Market Garden came to be.

Consisting of an airborne operation code named Market and a ground operation code named Garden, this combined operation by British, American and Polish forces was to drive a huge wedge in the German defense lines in the Netherlands. According to reports, only second rate forces were stationed in the area. This way, a decisive blow could be dealt to the German defense. By circumventing the feared German

Market Garden was approved and with it, one of the largest operations of the Second World War was launched. The result is well known. Regardless of all discussions about this, it can be said that overestimation of the Allied logistic capabilities and underestimation of the German troops in the area have prevented Operation Market Garden from reaching its objectives.

Definitielijst

- Heeresgruppe

- The largest German ground formation and was directly subordinate to the OKH. Mainly consisting of a number of “Armeen” with few directly subordinate other units. A Heeresgruppe operated in a large area and could number several 100,000 men.

- marshal

- Highest military rank, Army commander.

- Westwall

- Also known as Siegfried Line, the German defence line along the German-French border.

Plans for attack

After the battles in Normandy and in northern France, the Allied advance was split up in three groups. General Dwight Eisenhower, Commanding Officer Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Forces (SHAEF), was in command of three simultaneous campaigns. Field Marshall Bernhard Montgomery was in charge of the 21st Army Group which was successfully advancing north and approaching the Dutch border. From the south of France, 6th Army Group, commanded by Lieutenant-general Jacob L. Devers [3] was moving north. This army group encountered fierce resistance from the German troops they were facing. Between those two, 12th Army Group commanded by Lieutenant-general Omar N. Bradley[4] was advancing eastwards to the River Rhine and the German border

These three campaigns demanded many logistic efforts. Due to the ever increasing length of supply lines, Montgomery proposed, as early as August, to switch strategy. Supplying three campaigns simultaneously would be impossible He proposed to allow his 21st Army Group, supported by the US 1st Army, commanded by Lieutenant-general Courtney H. Hodges to advance northwards. To this end, the bulk of the supplies should be sent to his 21st Army Group. Montgomery argued that German resistance against his troops was as good as destroyed. A breakout in northerly direction would also have the advantage to knock out the launch sites of the V-1 and V-2 in the area. Subsequently, the French ports could be liberated and put to use. Montgomery even indicated he would be willing to serve under Lt-Gen. Omar Bradley if this would help to have his plan approved.

There was much opposition from the American side against the plan. Regarding their successes in Normandy, various American commanders were convinced that the US should be in charge of the further advance. Eventually, Bernard Montgomery managed to convince Dwight Eisenhower. This full turn of him had various causes. After Operation Overlord had ended, Air Chief Marshall Trafford Leigh-Mallory had closed the headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Air Forces and the participating units had been placed under their national command. The RAF regained command of her 2nd Tactical Air Force and the USAAF was again in charge of the 9th Air Force. On August 2, 1944, Eisenhower decided to integrate the airlanding components into the Combined Airborne Forces Headquarters of Lieutenant-general Lewis H. Brereton. On August 16, this was renamed First Allied Airborne Army. The intention was to achieve a fictitious US 1st Army Group to deceive the German intelligence services. This group was to consist of the US XVIII Airborne Corps (17th Airborne Division, 82nd Airborne Division and 101st Airborne Division) commanded by Major-general Matthew B. Ridgeway and the British 1st Airborne Corps (1st Airborne Division, 6th Airborne Division and 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade) commanded by Major-general Frederick Browning. The American Army command in Washington wished however that First Allied Airborne Army would be deployed in large operation soon. With his decision to put Montgomery and his 21st Army Group in command, Eisenhower decided to integrate this group into this army group. This way, Market Garden began to take shape.

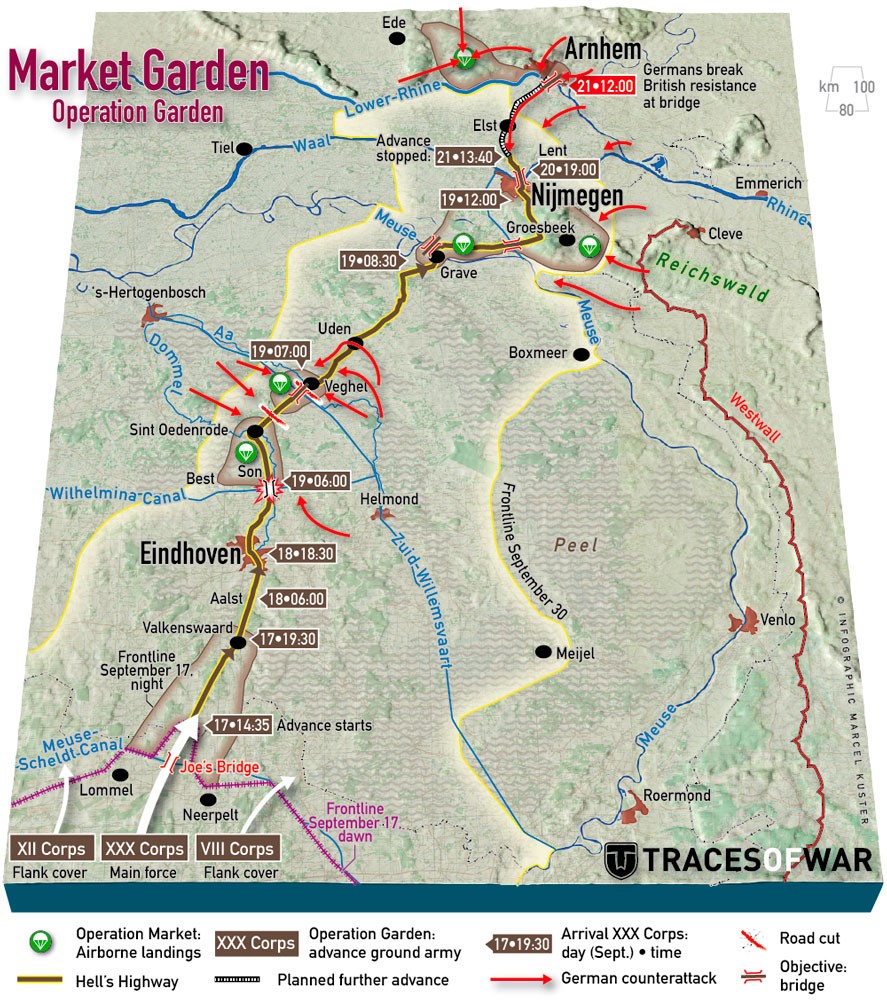

The plan entailed a speedy attack by British 2nd Army from a starting point on the Scheldt-Meuse canal to the north up to Nunspeet in the Netherlands near the Ijsselmeer. This attack would be supported by drops of the First Allied Airborne Army. The intention was to capture the bridges on the route of the advance, allowing it to proceed smoothly. After this advance, 2nd Army could push on towards the east to the heart of Germany. On September 10, 1944 the plan was approved by the Allied high command and Market Garden became a reality. The date of the operation was set at September 17, 1944.

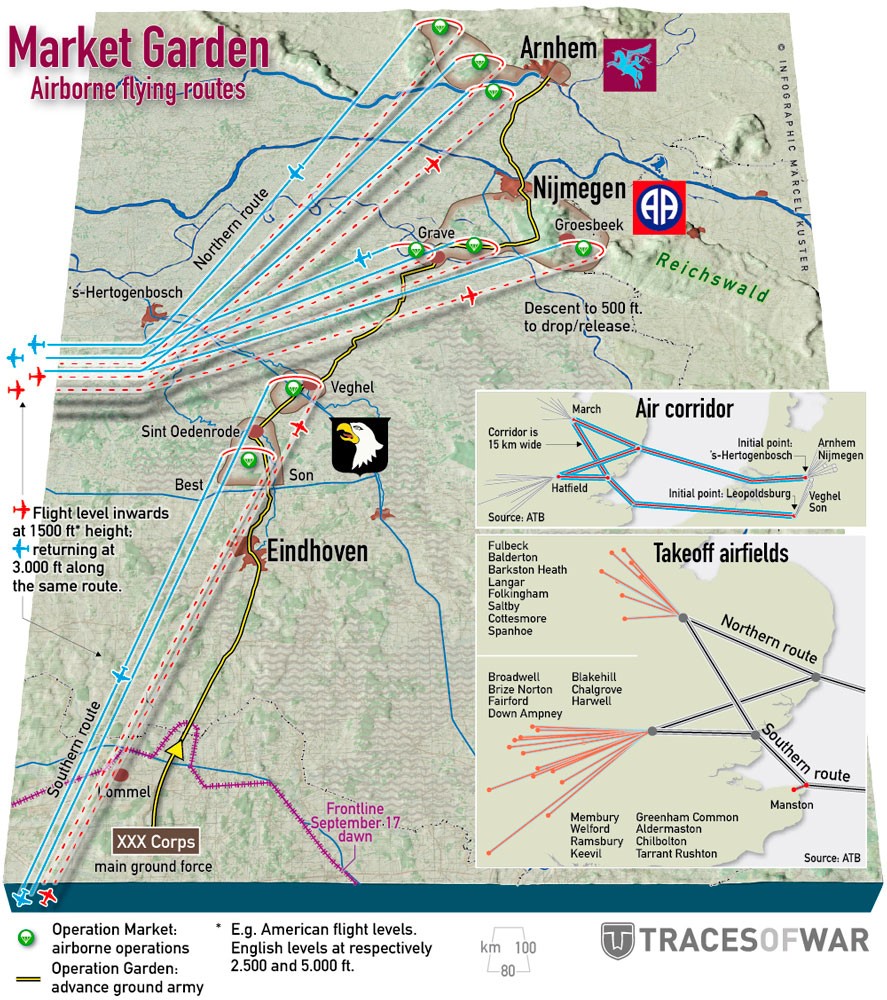

The airborne component, Market, was to see to the capture all bridges across all waterways at Eindhoven, Nijmegen and Arnhem. In the air landings, mainly RAF aircraft would be used to tow the gliders and aircraft of the USAAF would transport the paratroops. The transfer of all troops would take three days. On the fourth day, the 52nd Lowland Division would be flown in on transport aircraft to the captured Deelen airfield near Arnhem. Major- general Paul L. Williams, commanding officer of US IX Troop Carrier Command was one of the commanders who had insisted on a maximum of one transfer flight per day. He was supported in this by Lieutenant-general Lewis Brereton, commanding officer of the 1st Allied Airborne Army. More flights would be too strenuous on ground as well as on flying personnel, risking more losses. A direct consequence was that all three airborne divisions wouldn't be at full strength on the first day and would be compelled to maintain troops around the landing zones as those had to be kept open for future landings. The British 1st Airborne Division suffered an extra handicap as part of the aircraft destined for the unit was allocated to a group of the 82nd Airborne Division. In fact, they were to transfer 1st Airborne Corps’ Headquarters to Nijmegen as Major-general Frederick Browning had decided his HQ was to accompany the attack.

That first day, the troops in the first waves were to attack important strategic objects and defend the landing zones until all troops had arrived. At the same time, an area had to be held enabling the ground operation to advance through these captured areas. It was assumed that hardly or no resistance at all was to be expected from German side.

Initially, Major Brian Urquhart, Chief of Intelligence of British I Airborne Corps (not to be mistaken for Brigadier Roy Urquhart, commander of British 1st Airborne Division), voiced his doubts about this. He said messages from the Dutch resistance, indicating the possible presence of the German II. SS-Panzerkorps in the vicinity of Arnhem were utterly ignored. It had already been decided though that the operation should continue. Major Urquhart was compelled to take sick leave

The 1 Airborne Corps was placed in command of the entire landing operation, which comprised the British 1st Airborne Division, the American 82nd Airborne Division, 101st Airborne Division and the Polish 1st Independent Parachute Brigade Group. Allocation of the various tasks was the responsibility of Browning, ordering 101st Airborne Division of Major-general Maxwell Taylor to land near Eindhoven. The 82nd Airborne Division commanded by Brigadier-general James M. Gavin was to land near Grave and Nijmegen and finally, British 1st Airborne Division commanded by Major-general Robert E was to land near Arnhem in order to repulse counterattacks from the north. The British would be supported by the Poles.

Prior to the operation, British and American bombers were to attack airbases in the Netherlands from which German fighters could attack the transport aircraft, as well as Flak positions along the air lanes and around the landing zones. In addition, various German military installations, such as barracks and troop concentrations were to be bombed. British and American fighters were to escort and protect the air armada of bombers, transport aircraft and gliders.

In the night of September 16 to 17, 282 aircraft of RAF Bomber Command would attack airfields in the Netherlands and just across the border in Germany. In the early morning of September 17, another 100 RAF bombers would attack the coastal batteries on Walcheren and Schouwen-Duiveland after which over 800 American bombers would strafe the various Flak installations along the route. Meanwhile, 2nd Tactical Air Force would launch precision attacks on various targets such as barracks around Arnhem, Ede and Nijmegen.[5]

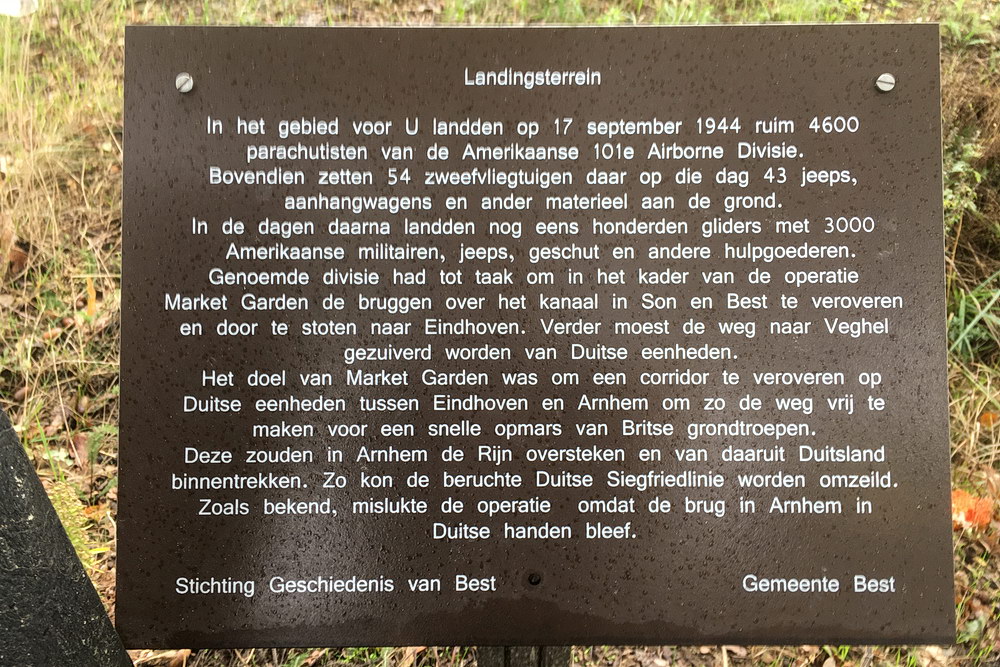

A little north of Eindhoven, two landing zones near Son and Veghel had been allocated to the 101st Airborne Division. The unit was to capture the bridges at Son, Sint-Oedenrode and Veghel. The 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR), commanded by Colonel Howard R. Johnson was to land on DZ-A (Drop Zone A) near Veghel and focus on the rail- and road bridges across the river Aa and the Zuid Willemsvaart near Veghel. 502nd PIR, commanded by Colonel John H. Michaelis was to land on DZ-B northwest of Son. They were to protect the area for the gliders which would arrive later. In addition, they were to capture the road bridge across the river Dommel near Sint-Oedenrode and, if possible, support 506th PIR in its advance on Eindhoven. This unit, commanded by Colonel Robert F. Sink, was to land on DZ-B and DZ-C and subsequently capture the bridge on the Wilhelmina canal near Son. Next, they had to advance on Eindhoven, capture the bridges across the Dommel and their secondary target, the road and rail bridge near Best.[6]

The 82nd Airborne was dropped on two locations as well. Southwest of Nijmegen near Grave to capture the bridges near Grave across the Meuse and the Meuse-Waal canal near Nijmegen. The largest DZ was located between Nijmegen Berg en Dal and Groesbeek where troops would land to capture Nijmegen and the bridges across the Waal. The bridge near Grave, code named Bridge Number 11[7] was allocated to 504th PIR, commanded by Colonel Reuben Henry Tucker III[8] and would land southwest of Nijmegen on DZ-O near Overasselt[9] A few smaller units were to land close to the bridge near Grave, their secondary target being the bridges across the Meuse-Waal canal. These were Bridge Number 7 (Heumen), Bridge Number 8 (Malden), Bridge Number 9 (Hatert) and Bridge Number 10 (Honinghutje).[10] The area between the bridge at Grave and the bridges across the Meuse-Waal canal had been selected for this purpose.

505th PIR, commanded by Colonel William E. Ekman was to land south of Groesbeek on DZ-N[11] and then take Groesbeek and the higher terrain between the town and the Meuse-Waal canal. 508th PIR commanded by Colonel Roy E. Lindquist was to land on DZ-T in the triangle Nijmegen, Groesbeek, Berg en Dal and cut off Nijmegen from that direction. In addition they were to capture the road and rail bridges across the Waal at Nijmegen. Apart from all these targets, 508th PIR was to be on alert to protect the landing zones against possible German pressure. Supporting 505th PIR, the 376th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion commanded by Lt-Col Wilbur M. Griffith was to land close to them and be ready to support 504th PIR.[12] 307th Airborne Engineer Battalion (Colonel Edwin A. Bedell) was to land on DZ-N between Mook and Groesbeek.[13] The battalion served mainly in support of the various other units and protecting the flanks of the landing zone. The other troops of 82nd Airborne would be flown in later.

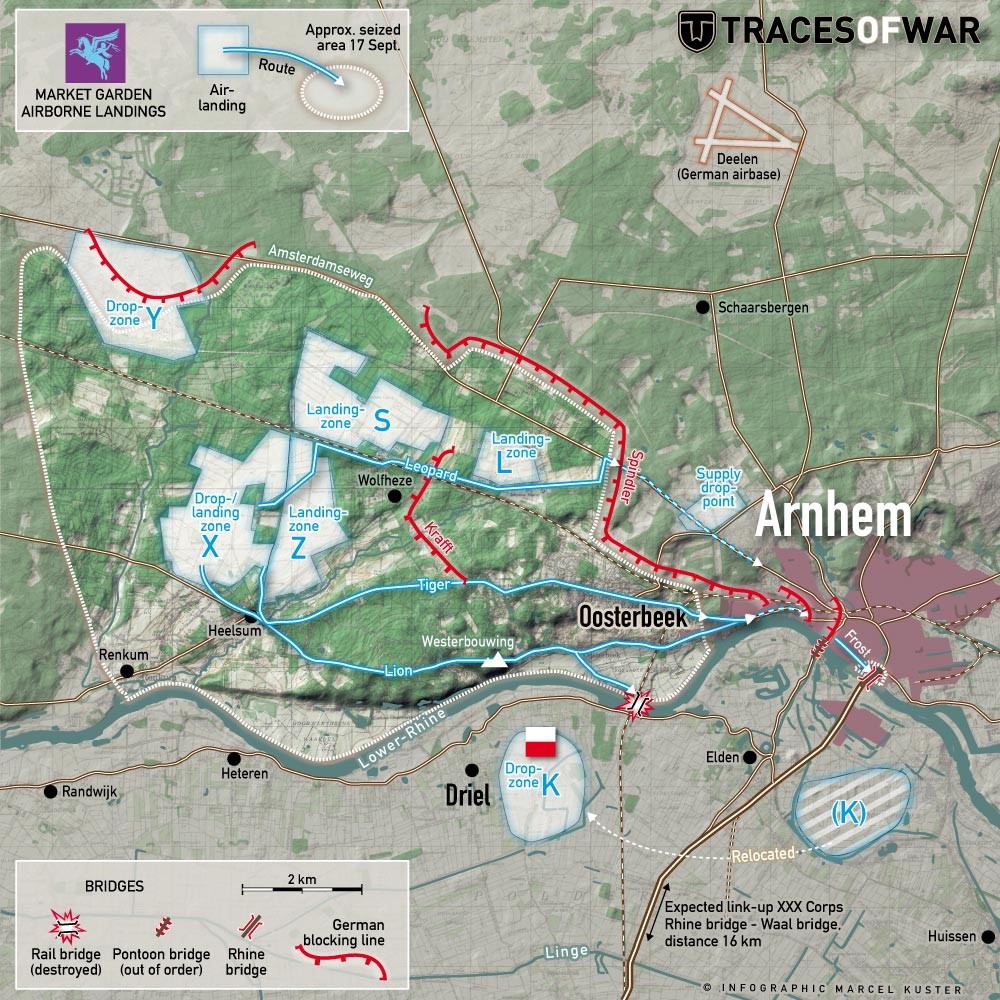

For operations around Arnhem, 1st Parachute Brigade commanded by Brigadier Gerald W. Lathbury), 1st Airlanding Brigade commanded by Brigadier Philip H.W. Hicks), Division Headquarters and various supporting units such as three batteries of 1st Airlanding Light Regiment commanded by Lieutenant-colonel William F.K. Thompson and the 1st Airborne Reconnaissance Squadron commanded by Major Charles Frederick Howard Gough) would be flown in first. These units would use the landing areas DZ-X, LZ-S (Landing Zone S) and LZ-Z. Shortly before landing the areas would be secured by Pathfinders of 21st Independent Parachute Company. The 1st Airlanding Brigade was to protect the areas for the benefit of the second landings the next day. 1st Parachute Brigade was to advance towards the bridge immediately and hold it until the arrival of the remainder of the division.

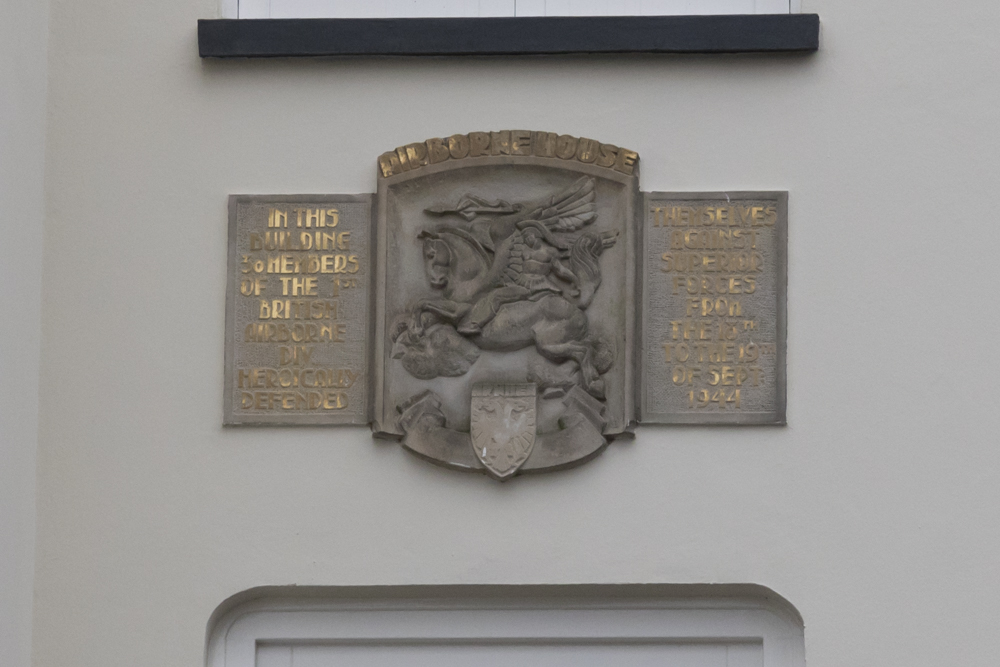

As the RAF, owing to heavy AA fire at the Arnhem bridge, didn't want to launch a surprise attack like the one in Normandy on Pegasus bridge, it was decided that 1st Airborne Reconnaissance Squadron would head for the bridge in their jeeps immediately after landing. They were to take it in a surprise attack and hold until 1st Parachute Brigade had reached the bridge on foot. Of this unit, 2nd Parachute Battalion, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel John Dutton Frost would head for the bridge along the Lower Rhine by a route code named Lion. They were to capture the railway bridge, the pontoon bridge and the road bridge in that order and secure them. 3rd Parachute Battalion commanded by Lt.-col. John A.C. Fitch, was to advance on the road bridge along the Utrechtseweg via the route codenamed Tiger. Finally, 1st Parachute Battalion commanded by Lt.-col. David Theodore Dobie was to strike for the bridge along the Amsterdamsestraatweg via a route codenamed Leopard in order to secure the ramps to and from the bridge on the higher terrain north of Arnhem

On the second day, 4th Parachute Brigade, commanded by Brigadier John Winthrop Hackett, would land on DZ-Y, together with the remaining units of 1st Airlanding Brigade and other supporting units of the division. Right after arrival, the entire division was to advance on Arnhem in order to seal off the city. On the third day, 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade Group, commanded by Major General Stanislaw Franciszek Sosabowski, would be flown in. His gliders were to land on LZ-L north of the Lower Rhine while the paras were to land on DZ-K south of the Lower Rhine. Finally, as soon Arnhem had been secured by 1st Airborne Division and airbase Deelen had been taken, 52nd Lowland Division, commanded by Major General Edmund Hakewill-Smith, would be flown in and join 1st Airborne Division.

Along this carpet of landings, the ground component Garden, XXX Corps, was to advance along a single, two lane highway. This corps would have the following units at its disposal: 2nd Household Cavalry Regiment commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Henry Abel Smith, Guards Armored Division commanded by Brigadier Allan Henry Shafto Adair, 43rd Wessex Division commanded by Lieutenant General Gwilym Ivor Thomas, 8th Independent Armored Brigade commanded by Brigadier George Erroll Prior-Palmer, 50th Northumbrian Division commanded by Major General Douglas Alexander Henry Graham and Royal Netherlands Brigade 'Prinses Irene' commanded by Colonel Albert Cornelis de Ruyter van Steveninck The Guards Armored Division was to take charge and if somewhere along the way, the unit should encounter a bridge not yet captured, 43rd Wessex Division was to force a crossing.

On the left flank, the advance would be supported by XII Corps, commanded by Lt.-gen. Neil Methuen Ritchie and on the right flank by VIII Corps, commanded by Lt.-gen. Richard Nugent O'Connor. Both corps were not at full strength however and both, in contrast to XXX Corps, hadn't yet established a bridgehead on the Meuse-Scheldt canal. Moreover, elements of these corps were still fighting Germans on other flanks of their positions and therefore could not be released to cover the flanks of XXX Corps.[14] Yet, operational plans were drafted for both corps in support of Market Garden.

1st Canadian Army had taken over the west flank of XII Corps as early as September 10. The corps itself had a bridgehead near Geel, just across the Meuse-Scheldt canal but for an efficient advance, 53rd Welsh Division, commanded by (Major General Robert K. Ross, would establish a new bridgehead near Lommel, advance from there via Turnhout and Tilburg towards ‘s Hertogenbosch and cross the Meuse there. For its flank operation, VIII Corps had 11th Armored Division, commanded by (Major General George Roberts and the Belgian 1st Infanterie Brigade, commanded by (Colonel Jean-Baptiste Piron at its disposal and would cross the Meuse-Scheldt canal near St, Huibrechts-Lille and subsequently advance via Helmond on Cuijk a.d. Maas

While the plans were being drafted, the Dutch government in exile in London was consulted closely. In support of the operation, the government ordered the Dutch Railway Company to call a general strike in order to thwart the movement of German troops. In addition, plans were made to organize and activate the resistance groups in the area. To this end, so-called Jedburgh teams were deployed in order to contact the resistance in the occupied areas and assist them as good as possible in activities to support the landing troops. In order to facilitate communication, Dutch military, mostly having been trained as commandoes, were allocated to various Allied units and the Jedburgh teams as interpreters, guides and communication experts.

As starting point of the ground operation of XXX Corps, the bridge on the Scheldt-Meuse canal (Kempisch canal) in Barrier (Lomnmel), also known as Groot Bareel was selected. This bridge was captured on September 10[15] by No. 1 Squadron, commanded by Major David Arthur Peel of 3rd Battalion, Irish Guards commanded by Lt.-col John Ormsby Evelyn Vandeleur. Due to the command by J.O.E. VandeLeur, this bridge was nicknamed Joe’s Bridge. On September 11, 1944, D Squadron commanded by Lieutenant Rupert Buchanan-Jardine, of the 2nd Household Cavalry Regiment commanded by Lt.-colonel Henry Abel Smith had made a reconnaissance of the area beyond the bridge. On the night of September 16, 1944 everyone stood poised to launch Operation Market Garden.

Definitielijst

- Bomber Command

- RAF unit which controlled strategic and sometimes tactical bombing (as in Normandy)

- Brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- Browning

- American weapon’s designer. Famous guns are the .30’’ and .50’’ machine guns and the famous “High Power” 9 mm pistol.

- Cavalry

- Originally the designation for mounted troops. During World War 2 the term was used for armoured units. Main tasks are reconnaissance, attack and support of infantry.

- Flak

- Flieger-/Flugabwehrkanone. German anti-aircraft guns.

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- RAF

- Royal Air Force. British air force

- Regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- SHAEF

- Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force, the Allied High Command in Western-Europe after the Normandy landings.

- Squadron

- A military unit in the Belgian navy usually six to eight small ships operating together under one command. The smallest military unit in the Dutch air force of about 350 men. In most countries is the designation of a military unit thesize of a company. It is either an independent unit, such as a battery, or part of a bigger Calvary unit. In the air force it is the designation of a unit of aircrafts.

- strategy

- Art of warfare, the way in which war should be conducted in general.

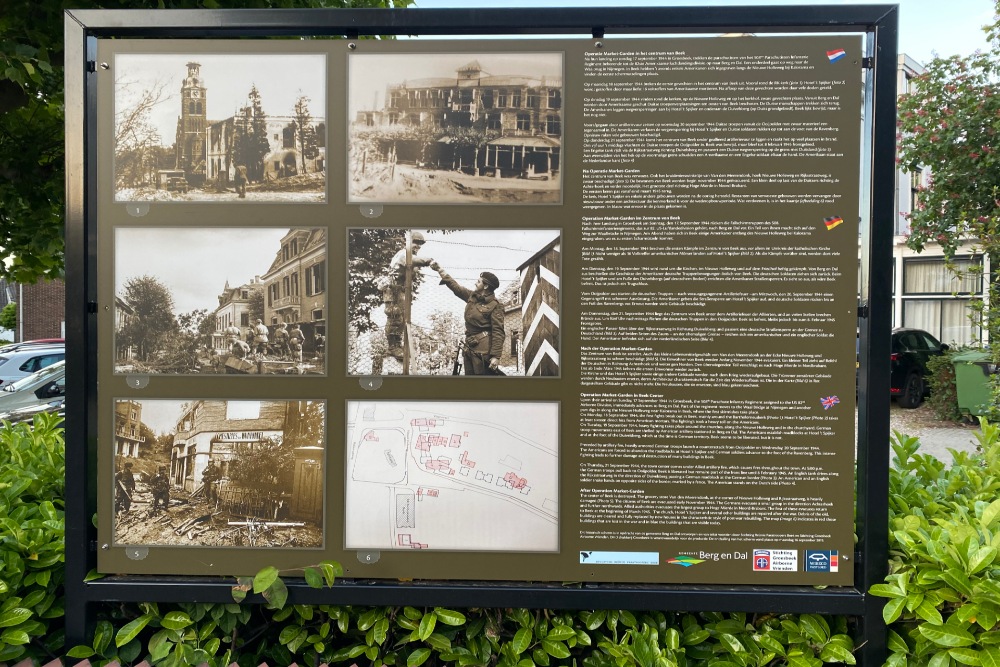

The German situation

Owing to the speedy advance of the Allies through northern France and Belgium, it looked like the Netherlands would be liberated soon. As a result, light panic broke out among the Germans. As early as September 2, 1944, Reichskommissar für die besetzten Niederländischen Gebiete Arthur Seyss-Inquart had ordered all German citizens to evacuate to the eastern part of the country. In case of danger, they could escape to Germany quickly. Seyss-Inquart entrenched himself in his bunker in Apeldoorn. Anton Mussert, the leader of the Nationaal Socialistische Beweging (NSB) also advised his party members to head in the direction of Germany. The capture of Antwerp on September 4 triggered panic the next day among German troops and members of the NSB. Many German military deserted and entire units withdrew head over heels towards Germany. The Dutch fell into the spell of an imminent liberation and started to celebrate. This day would later be known as ‘Dolle Dinsdag’ or Crazy Tuesday.

Crazy Tuesday. Germans are fleeing, Keizer Lodewijk Square, Nijmegen. Source: Regionaal Archief Nijmegen

To restore order, Oberbefehlshaber West, Generalfeldmarschall Walter Model was relieved of his function and appointed Befehlshaber Heeresgruppe B. September 5 Generalfeldmarschall Gerd von Rundstedt was named his successor. Walter Model faced chaos. His Heeresgruppe had actually been cut in two. 15. Armee commanded by General der Infanterie Gustav-Adolf von Zangen had been cut off south of the Westerscheldt and was desperately trying to escape to the north via Walcheren and Zuid-Beveland. 7. Armee commanded by General der Panzertruppen Erich Brandenberger, had been pushed back eastwards to Maastricht and Aachen by the Americans. Now there was a 75 miles gap through which various German units escaped in chaos. Walter Model ordered Generalleutnant Kurt Chill, who had virtually lost his entire 85. Infanterie Division, to pull the remaining units in the gap back in line. Model had ordered him to assemble the troops and withdraw to Germany. Kurt Chill however decided to have the units he could assemble dig in along the Albert canal. He placed officers near the most important bridges who were ordered to catch every German soldier who turned up and insert him in the line. In this way, the Germans managed to halt the retreat effectively.

A second action was ordered by Adolf Hitler. On September 4 he ordered 1. Fallschirm-Armee Generaloberst Kurt Arthur Benno Student to deploy his unit in the 75 mile gap between Antwerp and Maastricht. 1. Fallschirm-Armee was also under command of Heeresgruppe B. Kurt Student immediately contacted Kurt Chill and together they established a defensive line. Student set up his headquarters in Huize Bergen in Vught. He reorganized his own troops and merged various units in the area into Kampfgruppen.

Meanwhile, Gustav Adolf von Zangen managed to withdraw the better part of his 15. Armee to the Netherlands. He had the units which stayed behind establish a defensive line from Zeebrugge along the Gent-Brugge canal up to Antwerp. Here the line joined the line formed by Student’s troops. On September 12, 59. Infanterie-Division commanded by Generalleutnant Walther F.R. Poppe was transferred from 15. Armee to 1. Fallschirm-Armee. 59. I-D was deployed next to 245. Infanterie-Division commanded by Oberst Gerhard Kegler along the line Breda-Tilburg-Best.[16]

Kurt Student received 719. Infanterie-Division commanded by Generalleutnant Karl Sievers from Wehrmachtbefehlhaber General der Flieger Friedrich Christiansen. The unit was put into the line along the Albert canal, between Herentals and Hasselt, connecting to the 719. I-D. From September 6 onwards, 15. Armee was reinforced by Kampfgruppe Rink commanded by Oberstleutnant Berthold Rink, Kampfgruppe Ewald commanded by Hauptmann/Major Werner Ewald), Kampfgruppe Duchstein commanded by Hauptmann Duchstein and Kampfgruppe Jungwirth commanded by Major Hans Jungwirth.[17]

The troops which were regularly stationed in the Netherlands mainly consisted of trainings units of Heer, Kriegsmarine, Luftwaffe and Waffen-SS; units of sick and recovering military, regular units of Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe stationed on naval and airbases; regular Flak units of the Luftwaffe and the Reichsarbeitsdienst or RAD. From all these units, more or less operational Kampfgruppen, Alarmeinheiten and Sperrverbände were formed which could be deployed as strike forces, quick response units and defensive units wherever necessary. In addition, various units such as fighting or guard units were deployed which up till then only had a supporting role in the Netherlands. In Arnhem for instance, members of the Hochfrequenzforschung Einsatzstab Holland (Luftnachrichten-Funkleitstab 1) of the Luftwaffe, housed in the Christelijk Lyceum on the Utrechtseweg in Arnhem[18] were ordered to patrol the railway station and shunting yard in Arnhem to prevent acts of sabotage by the resistance which increasingly occurred on the Dutch railway network.[19] This example illustrates the deployment of a variety of units stationed in the Netherlands which were suddenly assigned military tasks without having been trained accordingly.

The regular forces in the Netherlands were commanded by the Wehrmachtsbefehlshaber Niederlände. When on September 4, 1944, the city of Antwerp was captured by the Allies, he already issued orders to reorganize the troops in the Netherlands into a new defensive line. He appointed General der Infanterie Hans von Tettau as commander. The defensive line which was to be established, was called the Waalstellung.[20]

This line, as the name suggests, more or less followed the river Waal through the Netherlands. It served mainly as a net to catch German units fleeing north. The troops on this line were to stop those units and return them to the front.

Around Arnhem/Nijmegen, this line was manned by SS-Unterführerschule Arnheim commanded by SS-Standartenfüher Michael Lippert from Arnhem and the Batallion Krafft commanded by SS-Sturmbannführer Sepp Kraft. This unit consisted of:

- Stab, 2. Kompanie commanded by SS-Hauptsturmführer Hans Heinrich Köhnken

- 4. Kompanie, commanded by SS-Obersturmführer Ernst Kauer

- , SS-Panzergrenadier-Ausbildungs und Ersatz Battalion 16.

Battalion Krafft had been wihdrawn from the Wasserstellung, somewhat comparable to the Hollandse Waterlinie, and transferred to Wolfheze where it arrived on September 4. In Arnhem itself, two other companies of Battalion Krafft had been billeted for some time: 7. (Stamm) Kompanie and 8. (Grenadier) Kompanie. These were combined by Krafft to form the 9. Kompanie commanded by SS-Obersturmführer Günther Leiteritz. Eventually, Sepp Krafft set up his headquarters in Waldfriede Mansion on the Johannahoeve estate near Wolfheze.

A trainings unit of Artillerie-Regiment 184 commanded by Hauptmann Breedemann was also stationed in Wolfheze. On September 11, they had received 40 105mm howitzers[21] of which many were deployed in the woods surrounding Wolfheze. These forces were supplemented by some reserve batallions of the Hermann Göring-Division: various Schiffs-Stamm-Abteilungen of the Kriegsmarine, Fliegerhorstbatallione of the Luftwaffe and AA batteries manned by RAD personnel. V Abteilung, SS-Artillerie-Ausbildungs und Ersatz-Regiment commanded by (SS-Hauptsturmführer Oskar Schwappacher) was stationed in the Betuwe near Oosterhout.

Wehrkreis VI commanded by General der Infanterie Franz Mattenklott was the nearest in Germany. The Wehrkreise were used as training and replacement unit for Infanterie and Panzertruppen. Wehrkreis VI also consisted of such units in various stages of training which could eventually be deployed. After the German forces had been defeated in Normandy, German high commanded ordered all Wehrkreise to reorganize their troop to so-called Kampfgruppen. These were tasked with defending their own Wehrkreis in case Allied forces entered the area. They could also be deployed as Alarmeinheit in neighboring areas. As Wehrkreis VI was closest to the Dutch border, its Kampfgruppen could eventually be deployed in the Netherlands. One of those groups was Kampfgruppe Knaust commanded by Major Hans Peter Knaust which consisted – on paper – of a staff batallion with Nachrichten-Zug and Pionier Zug, 4 companies of Panzergrendiere, 1 Panzer company and a Panzerjäger-Zug(Sf.).[22] This group was one of the units designated to head for the Netherlands in case of a threat. The units allocated to him would be taken from Panzergrenadier-Ausbildungs und Ersatz-Regiment 57, Panzer-Ersatz und Ausbildungs-Abteilung 11 and Panzerjäger-Ausbildungs und Ersatz-Abteilung 6. Hans-Peter Knaust himself was in command of Panzergrenadier-Ausbildungs-Bataillon 64.[23] Also 176. Infanterie-Division commanded by Oberst Christian-Johannes Landau) from Bielefeld could be dispatched to the Netherlands to fill the gaps. This division was eventually stationed between Hasselt and Maastricht. Panzer-Brigade 107 Major Berndt-Joachim Freiherr von Maltzahn was also sent to the Netherlands. This impressive armored unit equipped with PzKfw Panther V tanks had to be transported on many trains and its spearhead arrived in Venlo as late as September 18. Panzer-Brigade 107 as well as 176. Infanterie-Division were placed in command of LXXXVI. Armeekorps commanded by General der Infanterie Hans von Obstfelder. The fresh troops in Limburg would operate from September 12 onwards, commanded by Oberst Erich Walther to form Kampfgruppe Walther. Another unit which could reach the Netherlands on relatively short notice was Schwere Panzer-Ersatz und Ausbildungs-Abteilung 500 which was being trained Paderborn.

At that moment, German commanders were not aware of any Allied plan of attack, let alone it was assumed Market Garden was about to begin. Yet, German high command reckoned with various scenarios. Generally, two possibilities were taken into account based on intelligence reports. One possibility that had to be reckoned with, regarding the earlier progress of the advance, was an attack from the Allied positions along the Meuse-Scheldt canal. Another possibility was a landing by the British 4th Army on the Dutch coast. The Germans were unaware however that this British army was a fake. Germans took into account that that the 1st Allied Airborne Army was to support the advance by air landings behind the lines.

With all those caught, regular and new troops, German commanders did manage to establish a Sperrlinie from Zeebrugge all the way to Maastricht; the western side up to Antwerp being manned by 245. Infanterie-Division commanded by Generalleutnant Erwin Sander), 64. Infanterie-Division commanded by Generalmajor Knut Eberding and 712. Infanterie-Division commanded by Generalleutnant Friedrich-Wilhelm Neumann). Between Antwerp and Herenthals, 719. Infanteri-Division was deployed and connected to Kampfgruppe Chill up to Hasselt and 176. Infanterie-Division up to Maastricht. 7. Fallschirmjäger-Division commanded by Generalleutnant Wolfgang Erdmann) was deployed between Kampfgruppe Chill and the troops commanded by Christian-Johannes Landau. Various units were assembled behind these lines to fill eventual gaps. Kurt Student positioned his 1. Fallschirm-Armee in the center of this Sperrlinie, reinforced by various Kampfgruppen at strategic locations. Spread over the line, these were:

- Kampfgruppe Hoffmann commanded by Oberst Helmuth von Hoffman, Fallschirmjäger-Regiment 9

- Kampfgruppe Heydte commanded by Oberstleutnant Friedrich August Freiherr von der Heydte Fallschirmjäger-Regiment 6

- Kampfgruppe Segler commanded by SS-Hauptsturmführer Dr. Karl Segler, II. SS-Panzergrenadier-Regiment 19)

- Kampfgruppe Krause commanded by SS-Hauptsturmführer Gustav Krause, II. SS-Panzerartillerie-Regiment 9)

- Kampfgruppe Richter commanded by SS-Hauptsturmführer Friedrich-Wilhelm Richter, II. SS-Panzergrenadier-Regiment 21

- Kampfgruppe Röstel commanded by SS-Sturmbannführer Erwin Franz Rudolf Röstel, SS-Panzer-Sturmgeschütz-Jäger-Abteilung 10)

- Kampfgruppe Heinke commanded by SS-Sturmbannführer Heinrich Heinke, SS-Feld-Ersatz-Bataillon 10)

Student unified all these SS Kampfgruppen into one Kampfgruppe Heinke.

Apart from all these troops II. SS-Panzerkorps had been withdrawn to the Netherlands to recuperate from the battles in Normandy and to regroup and rearm. The unit had lost almost all of its operational tanks and was left with mainly broken down tanks. They still had many armored vehicles though. However, this unit wasn't placed under command of Walter Model but under the Army leadership in the Netherlands, Friedrich Christiansen. Commander SS-Obergruppenführer and General der Waffen-SS Wilhelm Bittrich set up his headquarters in Slangenburg Castle in Doetinchem and stationed his units mainly between Deventer and Arnhem.

SS-Kampfgruppe Hohenstaufen, also known as Kampfgruppe Harzer and consisting of the remnants of 9. SS-Panzer-Division Hohenstaufen was preparing to move to Siegen from this area in order to be rearmed. They were to leave between September 12 and 17. During the fighting in Normandy, the unit had been decimated to such an extent that it was temporarily degraded to a Kampfgruppe. At the time, the unit was commanded by 1a chief of staff of 9. Panzer-Division SS-Obersturmbannführer Walter Harzer. His work as chief of staff had been taken over temporarily by 1c (Adjutant) SS-Hauptsturmführer Wilfried Schwarz.[24]

From September 13 onwards, the various elements of the Kampfgruppe Harzer were reorganized to so-called Alarmeinheiten in order to be able to attack eventual air landings. Experiences in Normandy had taught the Germans that the Allies were able to conduct large scale landing operation behind the frontline. To this end, the various Alarmeinheiten were deployed on locations that enabled fast transport along main roads.

The other part of the corps, the remnants of 10. SS-Panzer-Division Frundsberg, commanded by SS-Oberführer Heinz Harmel, from September 7 SS-Brigadeführer, would depart from the area to Aachen but hadn't set a date yet. However, 2. Battalion SS-Panzergrenadier-Regiment 19, commanded by SS-Hauptsturmfürer Karl Heinz Euling from Rheden and an Abteilung SS-Panzerartillerie 9 which happened to be in Dieren on September 12 were temporarily added to 10. SS-Panzer-Division.

Both SS divisions were temporarily added to the German defensive line in Limburg. When they had to retreat further in order to reorganize in Gelderland, they both had to relinquish Kampfgruppen for the defense of the local front. For example, 10. SS-Panzer-Division ceded a reinforced battalion in the form of Kampfgruppe Heinke which was placed under command of 1. Fallschirm-Armee and stationed in Weert. Later on, this group was added to Kampfgruppe Walther. It would be this Kampfgruppe, deployed near Neerpelt close to the British bridgehead there, which would become the first obstacle for the ground operation of Market Garden. Oberbefehlshaber Heeresgruppe B Walter Model took residence in Hotel Tafelberg in Oosterbeek, unaware that right there and close by, the British 1st Airborne Division was going to land.

Definitielijst

- Abteilung

- Usually part of a Regiment and consisting of several companies. The smallest unit that could operate independently and maintain itself. In theory an Abteilung comprised 500-1,000 men.

- Armee

- German unit. Mostly consisted of three to six army corps and other subordinate or independent units. An Armee was subject to a Heeresgruppe or Armeegruppe and had in theory 60,000-100,000 men.

- Batallion

- Part of a regiment composed of several companies. In theory a batallion consists of 500-1,000 men.

- Brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- Fallschirmjäger

- German paratroopers. Part of the Luftwaffe.

- Flak

- Flieger-/Flugabwehrkanone. German anti-aircraft guns.

- Heer

- German army or land forces. Part of Wehrmacht together with “Kriegsmarine” and “Luftwaffe”.

- Heeresgruppe

- The largest German ground formation and was directly subordinate to the OKH. Mainly consisting of a number of “Armeen” with few directly subordinate other units. A Heeresgruppe operated in a large area and could number several 100,000 men.

- Jäger

- Also called fighter plane. Fighter planes can be used for air defence (armed with guns and/or carrying guided missiles) or for tactical purposes (armed with nuclear or conventional bombs or rockets). The aircraft used for tactical purposes are also called fighter- bombers because they are bombers with the speed and manoeuvrability of a fighter. Tactical fighters, equipped with photographic equipment are also used as reconnaissance plane.

- Kampfgruppe

- Temporary military formation in the German army, composed of various units such as armoured division, infantry, artillery, anti-tank units and sometimes engineers, with a special assignment on the battlefield. These Kampfgruppen were usually named after the commander.

- Kriegsmarine

- Germa navy. Part of the Wehrmacht next to Heer and Luftwaffe.

- Luftwaffe

- German air force.

- NSB

- National Socialist Movement. Dutch political party sympathising with the Nazis.

- Regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

- Reichskommissar

- Title of amongst others Arthur Seyss-Inquart, the highest representative of the German authority during the occupation of The Netherlands.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Waffen-SS

- Name of Military section of the SS.

Sunday September 17, 1944

The Air Armada

The air landings, code named Market were executed for the benefit of Operation Market Garden. The entire air operation around Market Garden entailed much more though than just the drops. Numerous squadrons were deployed to prepare, support and protect the entire operation.

On September 16, over 1400 bombers attacked various airfields and AA positions in the vicinity of the targets of the paratroops. In addition, German supply lines such as rail and road junctions were plastered. Shortly before midnight, 200 Lancasters and 23 Mosquitos of RAF Bomber Command launched attacks on German airfields in the north and the center of the Netherlands. The US 8th Air Force followed up with 862 B-17s attacking AA positions along the air lanes and the airfields near Eindhoven, Deelen and Ede. They were supported by 54 Lancasters and 15 Mosquitos of the RAF. Meanwhile, 85 Lancasters and 15 Mosquitos launched attacks on the island of Walcheren where many AA positions were located. In all these attacks, the Allies lost only two B-17s and three Mosquitos.

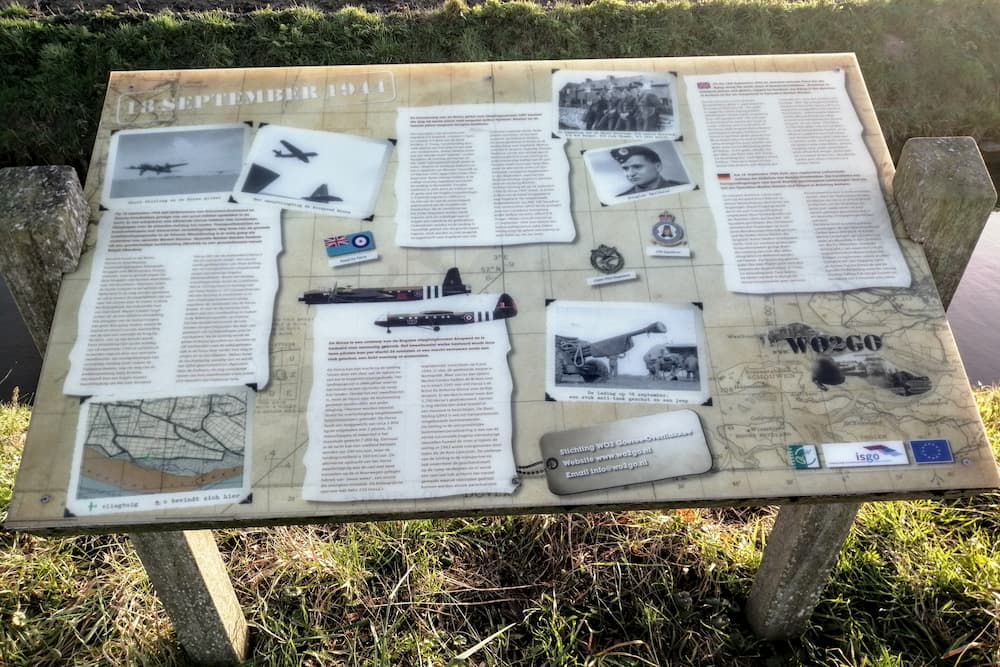

At 9:45 a.m. Dutch time, on Sunday September 17, 1944, the first aircraft of the landing operations took off from airfields in Great Britain. Via two assembly areas, Hatfield and March, they set course for the Netherlands. The troops of the 101st Airborne Division took a more northerly route whereas troops of the 82nd Airborne Division and the 1st Airborne Division took a more southerly route.

Even on September 17, between 11:38 and 11:41 a.m. bombers of the US 34th Bombardment Group (7th and 391st Bombardment Squadrons) carried out an attacks on German troop concentrations near Wolfheze,[25] a bombardment that caused more civilian lives than material damage.

XXX Corps on the starting line

At 11:00 hours, Lieutenant General Brian Horrocks watched from the roof of a factory the small bridgehead on the Meuse-Scheldt canal and the assembled strike force of Garden, the ground operation of Market Garden. Preceding XXX Corps was the Guards Armored Division commanded by Major General Allan H.S. Adair, made up of 5th Guards Armored Brigade commanded by Brigadier Norman G. Gwatkin and 32nd Guards (Infantry) Brigade commanded by Brigadier George F. Johnson.[26] The spearhead of the attack would consist of Irish Guards Group with 2nd Armored Battalion Irish Guards commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Giles A.M. Vandeleur and 3rd Battalion Irish Guards commanded by Lieutenant Colonel J.O.E. Vandeleur. Lieutenant J.O.E. Vandeleur was in overall command of the Irish Guards Group. Following the Irish Guards were 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division commanded by Major General G. Ivor Thomas) and 50th Northumbrian) Infantry Division commanded by Major General Douglas A.H. Graham. The tail was made up of 8th Independent Armored Brigade Group commanded by Brigadier George Erroll Prior-Palmer and the Prinses Irene Brigade commanded by Kolonel Albert C. de Ruyter van Steveninck. Everything and everyone stood ready to advance through the Corridor via Eindhoven, Son, Sint-Oedenrode, Veghel, Uden, Grave, Nijmegen, Elst, Arnhem to Apeldoorn, so the marching orders read.[27] Along the way, areas occupied by the enemy would be captured in order to make contact with the three airborne divisions that would occupy strategic locations along the route.

A Carpet of Aircraft

While XXX Corps was ready to strike, the 424 transport aircraft flew past along the southern route, carrying the paratroops of 101st Airborne Division commanded by Major-General Maxwell D. Taylor, destination Veghel, Sint-Oedenrode and Son. The other two divisions came in via the northern route. 1st Airlanding Brigade, commanded by Brigadier Philip Hicks with 320 gliders made up the first group and were to land a little after 13:00 on LZ-S and a small part on DZ-X. Within 30 minutes, they would be followed by 140 transport aircraft carrying 1st Parachute Brigade Group commanded by Brigadier Gerald Lathbury. They would land on secured DZ-X

The 424 Douglas C-47 transport aircraft (Dakota) carrying the 101st Airborne Division, supplemented by 70 Dakotas towing Waco gliders, took off at almost the same time as the 625 transport aircraft and 50 Dakotas towing the Waco’s carrying the 82nd Airborne Division commanded by Brigadier James M. Gavin. The aircraft towing the 38 Airspeed Horsa gliders of General Frederick Browning’s headquarters that were to land near Nijmegen as well flew between the aircraft carrying the 82nd. As these forces were being assembled in the air at 10:25, a dozen Short Stirling bombers and 6 Dakotas flew ahead carrying the Pathfinders who would mark the landing zones.

In the end, all these tow planes, over 500 gliders and 1,073 transport aircraft carrying over 20,000 paratroops and air landing units formed a carpet, 9 miles wide and 94 miles long.[28] This entire armada was escorted by over 1,500 fighters, the RAF protecting the northern and the USAAF the southern route. Along the entire route, bombers and fighter-bombers attacked German AA positions. 48 North American B-25 Mitchel bombers and 50 De Havilland Mosquitos attacked military targets around Nijmegen, Deelen, Ede and Cleve. German opposition was minimal but their fighters and AA guns shot down 68 larger planes, 71 gliders, 2 RAF and 18 USAAF fighters.

The Ground Attack gets under way

At 13:45 Brian Horrocks ordered the artillery barrage to start at 14:00 and the operation to start at 14:35. At 14:00 sharp 408 artillery pieces started shelling the German positions around Joe’s bridge, the bridgehead of XXX Corps. Right after the barrage, Major Desmond J.L. Fitzgerald, commander of 3rd Squadron Irish Guards ordered to commence the advance in the direction of Valkenswaard. At 14:35, the first tank commanded by Lieutenant Keith Hethcote, drove off. 1st and 2nd Squadron followed immediately with men of 3rd Battalion Irish Guards riding on their tanks. The artillery laid its fire in front of the tanks in support. Overhead, Hawker Typhoon fighter-bombers of RAF No. 38 Group,[29] provided air support.

Initial opposition was much stronger than expected. Kampfgruppe Walther, commanded by Oberst Erich Walther), lying in ambush along the road, managed to knock out nine tanks and two armored vehicles within a few minutes. West of the same road, Fallschirmjäger-Regiment 6 commanded by Oberstleutnant Friedrich August Freiherr von der Heydte, immediately joined in the fighting.[30] On the east side, Kampfgruppe Heinke commanded by SS- Sturmbannführer Heinrich Heinke), was deployed. A little west of Kampfgruppe Walther, Kampfgruppe Chill commanded by Generalleutnant Kurt Chill was deployed and to the east 7. Fallschirmjäger-Division. Hawker Typhoons were called in to knock out the German positions. It took several hours though before the advance could be resumed.

The Irish Guards, supported on its flanks by 2nd Battalion The Devonshire Regiment (2nd Devons), 231st Infantry Brigade commanded by Brigadier Alexander G. B. Stanier Bart, were the first to drive on. Before Valkenswaard however, the advance was stopped again by attacks of a Kompanie of Panzer-Brigade 107 with eight Stugs. Once more, Typhoons were called in to break the blockade.

At 16:30, the Irish Guards 1st Battalion, The Dorsetshire Regiment, reached the bridge on the Dommel near Valkenswaard which was still undamaged. From 17:00 hours onward, the Allied artillery could move up its line of fire close to Valkenswaard. During the advance, the Irish Guards had already lost 10 tanks. The Germans had managed to seriously delay this part of the advance. In the process however, part of Kampfgruppe Hoffman Fallschirmjäger-Regiment Von Hoffman, commanded by Helmuth von Hoffman was destroyed and Kampfgruppe Heinke commanded by Heinrich Heinke was compelled to withdraw to Achel and Kampfgruppe Kerutt commanded by Major Hellmut Kerutt to Schaft. Around 19:30, the Grenadier Guards Group managed to reach Valkenswaard itself. The advance however had come to a stop that day. The stretch was off and to advance during the night against the unexpected resistance and without air support was considered irresponsible.

A Favorable Pause for Kurt Student

At nightfall around 19:30, the spearhead of XXX Corps, the Guards Armored Division, had advanced up to Valkenswaard whereas they should have reached Eindhoven by then.[31], Thanks to the lull in the fighting, Kampfgruppe Walther was able reorganize and reinforce its defensive positions along the road to Eindhoven.

Meanwhile, Generaloberst Kurt Student found himself in a difficult position. His 1. Fallschirm-Armee had been split in two sectors due to the air landings. In addition, he had trouble maintaining contact with his units. A reconnaissance patrol brought him a lucky break however. South of Dongen, near the Wilhelmina canal, an Airspeed Horsa glider had come down. The aircraft, nr. 413[32] had been compelled to make an emergency landing because of a broken tow cable. The glider was part of A Squadron, No. 8 Group, transporting the headquarters of General Frederick Browning. Its crew consisted of pilots Staff Sergeant Jock Campbell and Sergeant David Monk and in addition Sergeant Russell D. Greenhalgh, Captain Joseph Peter Astbury, Signaler Watty Adamson, Signaler David H. Fulton, Code Operator Harold Chapman and Lieutenant Prentiss (101st Airborne Division Liaison Officer). On landing they had been attacked by a group of German soldiers and Sergeant Greenhalgh was killed. After interrogation and having searched the plane, the Germans found a document, probably the day order of the 101st airborne Division. As Kurt Student was unable to contact Walter Model, it was impossible to pass on the information in this document. Student himself was now well aware of the route of advance of XXX corps, the landing zones and the goals of the 101st. The document also included the transport schedule of September 18 and 19. Using this information, Kurt Student was able to reorganize his forces, turning the splitting of his forces to his advantage. He knew the Allies were advancing through a corridor and he could deploy his troops in a manner enabling him to attack this corridor from both sides. In general, his LXXXVI. Armeekorps, commanded by General der Infanterie Hans von Obstfelder was deployed east of the Allied advance and LXXXVIII. Armeekorps, commanded by General der Infanterie Hans-Wolfgang Reinhard) to the west of it. He sent Kampfgruppe Huber Major Huber. Grenadier-Regiment 1035, parts of Grenadier-Regiment 1036 of the 59. Infanterie-Division and Flak-Abteilung 424 to Best as well.

Kampfgruppe Huber was ordered to take the road itself near Sint-Oedenrode. To this end, he had Grenadier-Regiment 1035 at his disposal, four Jagdpanthers, a few units of the 17. Luftwaffen-Feld-Division and of Luftwaffen-Jäger-Regiment 36, Kampfgruppe Köppel (Flak-Brigade XVIII) and Heeres-Flak-Artillerie-Abteilung 284.

Meanwhile, XII Corps, commanded by Lieutenant-general Neil M. Ritchie, that was to cover one of the flanks of XXX Corps, had swung into action as well, preceded by 15th (Scottish) Division and 53rd (Welsh) Division, was soon delayed as they were engaged in fierce battle with Kampfgruppe Chill. For this corps, the delay would become typical for their progress and the lack of flank cover during the rest of the advance.

The Landings of 101st Airborne Division

The men of 101st Airborne Division, commanded by Major-general Maxwell Davenport Taylor were flown to their DZ and LZ near Best, Son, Sint-Oedenrode and Veghel in 424 transport aircraft. 70 Dakotas towed gliders with the additional equipment, supplies and the crews. They were tasked with capturing the bridges on the Aa, the Zuid-Willemsvaart, the Dommel and the Wilhelmina canal. Subsequently the division was to advance on Eindhoven in order to make contact with XXX Corps and guarantee a safe passage to the area of 82nd Airborne Division.

The primary targets of 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR) commanded by Colonel Howard R. Johnson were the bridges near Veghel. 1st Battalion commanded by Lt-col Harry W.O. Kinnard should land on DZ-A near the railway bridge on the Aa. However, the unit had jumped mistakenly around 13:00 over Heeswijk, on the wrong side of the river. Around 16:00 he managed to reach Veghel nonetheless, capture the railway bridge supported by 2nd Battalion and take Veghel. 2nd Battalion commanded by Lt.-col Robert A. Ballard and 3rd Battalion commanded by Lt.-col Julian J. Ewell had landed on the correct DZ near Veghel. 2nd and 1st Battalion, which had come later, captured the railway bridge on the Aa together as well as the road and railway bridge on the Zuid-Willemsvaart. Meanwhile, 3rd Battalion had managed to close the road between Veghel and Sint-Oedenrode a little after 15:00. With this road block by 3rd Battalion, 1st and 2nd Battalion set up a defensive line around Veghel.

502nd PIR commanded by Colonel John H. Michaelis landed on DZ-B near Sint-Oedenrode. Here, 1st Battalion commanded by Lt.-col. Patrick J. Cassidy went straight to Sint-Oedenrode, captured the town and the road bridge on the Dommel. To this end, the battalion had a short engagement with units of Flieger-Regiment 93, part of Kampfgruppe Gotsche commanded by Generalmajor Reinhold Gotsche whose command post was located in town.[33] 3rd Battalion commanded by Lt.-colonel Robert G. Cole set up the defense of the LZ because of the arrival of the gliders later that day and took up various defensive positions along the route of the advance. H Company commanded by Captain Robert E. Jones) of 3rd Battalion was sent to the bridge on the Wilhelmina canal near Best. The bridge had been marked as secondary target but because the other bridges had been captured relatively easy, it was decided to capture this one as well. The reinforced company advanced through the Son forest and on reaching the edge of the forest in the west, they ran into a firing line of Kampfgruppe Rink. This unit had established a defensive line with Feld-Ersatz-Bataillon 347 and I. Bataillon, SS-Polizei-Sicherungs-Regiment III, and four AA guns on an intersection in Best on the road from Eindhoven to Boxtel. H. Company attempted to have the platoons advance further from various sides in a surrounding movement but the opposition was too strong for one company. Hence, he had Lt.-col. Cole informed and asked for reinforcement. At that moment, a German column approached from Boxtel with 12 trucks and two mechanized 20mm guns. This was the reinforcement of 245. Infanterie-Division in Best. Meanwhile, Lt.-col. Cole had the rest of 3rd Battalion advance on Best at 18:00. They didn't manage however to drive the Germans out on September 17. Because of the speedy capture of the targets allocated to the regiment, 2nd Battalion, commanded by Lt.-col Steve A. Chappuis could be held in reserve.

506th PIR, commanded by Lt.-col. Robert F. Sink, landed without much resistance on DZ-C on the Sonse Heide. All battalions advanced on Son after landing. 1st Battalion, commanded by (Lt.-col. James L. LaPrade made its way through the woods and across the fields. 2nd Battalion, commanded by (Lt.-col. Robert L. Strayer advanced along the highway to the road bridge on the Wilhelmina canal. 3rd Battalion, commanded by (Major Oliver M. Horton followed the route of 2nd Battalion as reserve. On nearing Son, the unit was subjected to fire from three 88mm guns and its protecting unit. They managed to knock out the obstacle and continued towards the bridge. As they neared the bridge, it was blown by the Germans. Its defense was made up by Kampfgruppe Fullriede, commanded by Fritz Fullriede, II. Abteilung, SS-Panzer-Ersatz und Ausbildungs-Regiment Hermann Göring. Covered by 2nd Battalion, 1st Battalion moved forward and after a few men had crossed the canal by swimming and in a rowing boat, they managed to put the defenders to rout. A platoon of Company C, 326th Airborne Engineer Battalion managed to construct a foot bridge within two hours.[34] At 23:00 the entire regiment had crossed the canal. Subsequently, Company A and D captured the town itself against minimal resistance. They found the two bridges already blown.

The Landings of 82nd Airborne Division

82nd Airborne Division commanded by Brigadier-general James Maurice Gavin was transported in 482 Dakotas. They carried out air landings near Grave to capture the local bridge on the Meuse near Overasselt, to capture the road and railway bridge on the Waal at Nijmegen and the high ground near Groesbeek. The latter was intended to close off the approach from Germany through the Reichswald and to protect the landing zones. Some 50 tow planes brought the gliders in carrying A Battery, 80th Airborne Anti-Aircraft & Anti-Tank Battalion.[35]

The air armada carrying the troops of 82nd Airborne ran the gauntlet flying over the occupied Netherlands. Various transports and gliders were forced to make emergency landings or were shot down.

504th Parachute Infantry Regiment, commanded by Lt.-col. Rueben H. Tucker flown in on 137 Dakotas. The first paras of the regiment landed at 13:15 on DZ-O[36] near Overasselt. They had been preceded at 12:47 by two aircraft that had dropped a group of Pathfinders. The majority of these troops was designated to capture the four bridges, code named Bridge 7, 8, 9 and 10 on the Meuse-Waal canal. Right after landing, Major Willard E. Harrison, Commanding Office 1st Battalion, directed the men of B Company, commanded by Captain

Thomas C. Helgeson, to the bridge on the Meuse-Waal canal near Heumen, Bridge 7, right after landing according to the plan of attack and C Company commanded by Captain Albert E. Milloy to Bridge 8 on the same canal near Malden. A Company was held in reserve to jump in wherever necessary. Around 15:30, B Company reached Bridge 7 at Heumen.[37] The unit was almost immediately subjected to enemy fire from the island in the canal. At 16:00, a first attempt was made to cross the first bridge to the island. A number of men managed to cross it but were soon stopped in their tracks by German defensive fire. Around 16:45 some reinforcements set foot on the island and at 17:00 an attempt was made to push through to the other bank. German defensive fire halted all progress though. 3rd Platoon of A Company was sent in to give additional fire support. The attack was resumed at 19:30 and after heavy fighting a report was made around 23:00 that the bridge near Heumen had been captured.[38]

After having landed near Overasselt, C Company, commanded by Captain Albert E. Milloy, struck in the direction Malden in order to take the bridge on the Meuse-Waal canal (Bridge 8). To achieve this, C Company was reinforced by Headquarters Company.[39] Towards 14:15 They advanced towards the bridge and 1st Platoon, commanded by Lieutenant Howard A. Kemble[/bioid launched a frontal attack while 2nd Platoon[40] jumped north of the bridge in the southern sector of DZ-O while E Company commanded by Captain Walter S. Van

Spoyck, had its Special DZ south of the bridge. From Molenhoek, the attack could be supported by four 81mm mortars.

Prior to landing, Lt.-col. Wellems had instructed his officers that capturing the bridge was essential and hence, priority had to be given to reaching the bridge as soon as possible over moving to the designated assembly point.[41] Consequently, a mixture of units moved into the direction of the bridge immediately after landing. As early as 13:45 a small group commanded by Lt. William L. Watson reached the northern ramp. The only resistance they encountered were Germans in fox holes while a casemate equipped with a 20mm gun had been evacuated

During the landing of E Company, the aircraft of Lt. John S. Thompson carrying 15 paratroops had dropped them too late, causing them to land closer to Grave at some 650 yards southwest of the bridge, much closer than E Company. After a few skirmishes on the road leading to the southern ramp, he and his men knocked out the two casemates armed with two 20mm AA pieces. Next they knocked out the defense around pumping station Sasse and took up positions at the southern ramp of the bridge. The capture of this southern ramp at 14:15 completely surprised the Germans.

Around 14:30 the rest of 2nd Battalion arrived and the northern ramp itself was secured. The unit was subjected to fire from both sides of the northern bank from German positions with 20mm pieces and patrols were sent out to dislodge them. Fire support was given by an undamaged 20mm gun which had been captured near the bridge. At 15:35, the enemy fire was silenced and the bridge at Grave was firmly in American hands. Around 15:30 the entire northern bank around the bridge had been cleared of all German resistance. 2nd Battalion took up positions around both ramps in order to repulse possible German counterattacks. Lieutenant John M. Bigler, C Company, 307th Airborne Engineer Battalion subsequently set about removing all explosives with which the bridge had been mined.[42] Meanwhile, 3rd Battalion had taken up defensive position on the road Grave-Nijmegen.

505th PIR commanded by Colonel William E. Ekman landed on LZ-N/DR-N. This zone was located on the Knapheide near Klein Amerika south of Groesbeek. The unit was tasked with capturing Groesbeek itself, sealing off the Reichswald and capturing the railway bridge near Mook.[43] After having achieved these goals, the unit was to secure the entire southern approaches to the landing zone and Nijmegen. LZ-N/DZ-N were to be secured as 82nd Airborne Headquarters and part of the 307th Airborne Engineer Battalion commanded by Colonel Edwin A. Bedell would land here right after the initial landings. Some 20 minutes later, part of the 376th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion and the spearhead of 456th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion would follow. Apart from the gliders carrying the artillery, part of the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment would arrive. In addition, another 6 Waco and 32 Horsa gliders carrying 1st Airborne Headquarters of Lt.-gen. Frederick Browning would land on LZ-N. James Gavin set up the headquarters of 82nd Airborne in Hotel De Wolfsberg in Groesbeek.

Towards 15:00 Groesbeek was secured by 3rd Battalion commanded by Major James L. Kaiser of 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment.[44] Afterwards the unit was deployed in defense northeast and southeast of Groesbeek and LZ-N. The focus was on the German border. While capturing Groesbeek, 3rd Battalion had been supported by 2nd Battalion, commanded by (Lt.-col. Vandervoort-Benjamin-Hayes.htm"> Benjamin H. Vandervoort which had landed on DZ-T. Subsequently, this unit secured the Hoge Hoenderberg at 15:45 and Vandervoort sent out patrols in the direction of the bridges on the Meuse-Waal canal near Heumen and Malden. Meanwhile, 1st Battalion had taken up positions between Groesbeek, Riethorst and Mook enabling them to control the road between Nijmegen and Gennep. The railway bridge at Mook could no longer be captured as the Germans had blown it at 19:00.

The first men of 508th PIR, commanded by Colonel Roy E. Lindquist who jumped over DZ-T at 13:28, were members of 1st Battalion commanded by Lt.-col. Shields Warren. DZ-T was situated near de Wylerbaan, Voxhill and the Den Heuvel estate. Some 40 minutes later, the unit made its way through the woods between Groesbeek and Nijmegen towards their first target: De Ploeg, southeast of Nijmegen in the vicinity of the Heilige Landstichting. Hardly any resistance was encountered and they dug in near de Ploeg. At 18:25 Colonel Lindquist established the Regimental Command Post here.[45]

At the same moment, a platoon of C Company commanded by Lieutenant Robert J. Weaver with the S-2 section and two squadrons light machineguns had been sent to the Waal bridge via a direct route to assess the situation. Before they could have dug in near De Ploeg, Colonel Lindquist ordered Lt.-col. Shields Warren and his 1st Battalion to make their way to the Waal bridge and take it. This order was issued around 19:00 after James Gavin had informed Roy Lindquist not to wait any longer to attack the bridge. Although Roy Lindquist had clearly been ordered to attack, it still remains unclear how strict these orders were. Interviews and sources after the war indicate that Lindquist had been ordered to send his 1st Battalion to the bridge as soon as he considered this possible and responsible. Colonel Lindquist, a cautious commander by nature, therefore only swung into action after having been urged to by General Gavin personally.[46] By giving space to Lindquist’s own interpretation, it looked like General Gavin had possibly created a delay himself. In contrast to the advice given by Gavin – take the route through the suburbs of Nijmegen – A and B Company were sent to bridge through the center of town because this led past the headquarters of the resistance in Nijmegen so they could gather information about the Germans first.

2nd Battalion, commanded by Major Otho E. Holmes headed for the bridges on the Meuse-Waal canal near Hatert, which they were to capture in support of 504th PIR. D Company was left behind on DZ-T to protect the area. 2nd Battalion would have to cover a long distance though before reaching their targets and they could only achieve this during the night.

Meanwhile, troops of 3rd Battalion, commanded by Lt.-col. Louis G. Mendez had arrived at their defensive positions east of the Waal bridge around Berg en Dal. The battalion had been dropped at 13:36 over the landing zone and had captured Berg en Dal around 16:30. Around 18:30, G Company, commanded by Captain Russel C. Wilde was sent forward for a reconnaissance in the direction of the bridge. Forward patrols had already reported there was little resistance on the approaches to Nijmegen. Towards sunset, G Company had settled on Hill 64.6, a short distance from the bridge.[47] Around 20:00 they were in a perfect position to launch an attack on the still poorly defended bridge.[48] They had no orders though to capture it but had to defend the approaches to the landing zones from this direction.

Meanwhile, 1st Battalion had commenced its advance and push through to the Keizer Karelplein against little resistance for a first attack on the Waal bridge. On arrival, the unit was subjected to fire from German armored vehicles. The Americans had run into troops of SS-Panzeraufklärungs-Abteilung 9 which had been sent into the Betuwe and were reconnoitering Nijmegen as well. After a few skirmishes, the Americans managed to reach the Keizer Karelplein.

Kampfgruppe Hencke, commanded by Oberst Friedrich Hencke Fallschirmjäger-Lehrstab 1, had reinforced its positions around Keizer Karel and Keizer Lodewijkplein. The Kampfgruppe was made up of various units stationed in and around Nijmegen. Friedrich Hencke commanded his own Fallschirmjäger-Lehrstab 1 and II Batallion, Fallschirmjäger-Panzer-Ersatz und Ausbildungs-Regiment ‘Hermann Göring’. This last unit was equipped with some light PzKpfw II tanks which were deployed around the road bridge. Hencke also commanded Kampfgruppe Runge of SS-Sturmbannführer Otto Runge with a company of the SS-Junkerschule, Regiment Hermann Göring, three companies of Ersatz und Ausbildungs-Bataillon 6, 406. Landesschützen-Division and some other smaller units. Other groups commanded by Hencke were Kampfgruppe Melitz of Major Engelbert Melitz) with guard and police units, Kampfgruppe Ahlhorn of Major Ahlhorn and elements of Grenadier-Ersatz und Ausbildungs-Batallion 365. Hencke also had 4. and 5 Kompanie, 14. Schiffstamm-Abteilung, 4. Batterie, Schwere Flak-Abteilung 572 and a Flak-Ersatz-Abteilung at his disposal.[49] A short visit was paid by vehicles of SS-Panzeraufklärungs-Abteilung 9 commanded by SS-Hauptsturmführer Viktor Gräbner on a reconnaissance patrol who came to take a look in Nijmegen as well. After a short fight around the Keizer Karelplein, the armored vehicles returned to Elst.

Meanwhile, the main attack from Keizer Karelplen to the bridge continued. At that moment however, the Germans launched a strong counterattack, causing the Allied attack to falter before it had even begun. The Americans were compelled to withdraw to an area around Keizer Karelplein. Yet, scattered groups of paras managed to reach the bridge or its vicinity and waged a ferocious battle against the strong German defense which had assembled in the meantime. Some groups of paras were cut off from the main body and had to go into hiding until a new attack on the bridge would be launched on September 19. Captain Jonathan E. Adams even led a patrol of platoon strength in the night, reaching the Belvèdere Tower. Switchboards possible intended to blow the bridge were destroyed and two members of the patrol even managed to reach the bridge itself.[50] After the first attack had failed, it was decided to attempt a second the next day by another route.

The Landings of the British 1st Airborne Division

A fleet of 145 transport aircraft and 358 planes towing gliders brought the first wave of 1st Airborne Division in.

A little after 13:00, 1st Airlanding Brigade – without A and C Company, 2nd South Staffordshires as indicated – landed on LZ-S or Reijerscamp. Out of the 153 gliders that had taken off, 19 were lost or returned to England for various reasons. At 13:19, gliders of Divisional Headquarers landen on LZ-Z, the Renkumse Heide, carrying almost half of the divisional units, the Reconnaissance Squadron, two batteries of the 1st Airlanding Light Regiment and the vehicles and anti-tankguns of 1st Parachute Brigade. Of the 167 gliders destined for LZ-Z, 17 were lost or returned to England. The other gliders landed without noticeable opposition. Only a few German military were able to react but this resistance was soon repulsed. A few gliders crashed on landing, especially the larger General Aircraft Hamilcars which apparently had trouble with the landing terrain. These gliders mostly carried the heavier equipment.

At 13:40, the last glider had landed. Shortly afterwards, 1st Parachute Brigade was dropped on LZ-X/DZ-X on the Renkumse Heide, along with the majority of the men of the Reconnaissance Squadron. These landing progressed fine as well without German resistance worth speaking of. Right after landing it was discovered that the radio equipment didn't function properly. This completed the first landing near Arnhem.

While 1st Parachute Brigade was preparing to make its way to Arnhem, 1st Airlanding Brigade started digging in around the landing zones in order to defend them against possible German attacks. Two platoons of 2nd South Staffordshires occupied the town of Wolfheze while the rest of the battalion protected the northeastern side of LZ-Z. 1st Battalion, The Border Regiment (1st Borders) settled around DZ-X and LZ-Z to defend them. The unit was under temporary command of Major H.S. Cousens as the glider carrying Lt.-col, Tommy Haddon had to return to England because of problems. A Company commanded by Major Thomas Montgomery took care of the northern sector near the railway. D Company commanded by Captain William K. Hodgson occupied Heelsum and B Company commanded by Major Tom Armstrong occupied Renkum and in particular the brick factories in the forelands from where they could block the approach from Arnhem, the Utrechtseweg. C Company commanded by Major William Neill took up positions on the eastern edge of the terrain.

7th King's Own Scottish Borderers commanded by Lt.-gen. Robert Payton Reid headed for the Ginkelse Heide to DZ-Y. 4th Parachute Brigade would land there on the second day. A Company commanded by Major Robert G. Buchanan occupied the road between Arnhem and Ede, the Amsterdamseweg (today Verlengde Arnhemseweg). B Company commanded by Major Michael B. Forman) occupied the edge of the forest on the western side with C Company commanded by Major G.M. Dinwiddie along the railway Arnhem-Utrecht. D Company commanded by Major Charles Gordon Sherriff protected the southeastern edge of the forest. This operation was carried out without noticeable opposition as well.

The landing zones of the British were located some 8 miles from the bridges at Arnhem. During the advance, the British met strong German opposition immediately. It transpired they had encountered the remnants of two SS Panzer divisions which were recuperating around Arnhem from the fighting in France. During the advance to the city, only part of the Airbornes could be deployed that day. 1st Airborne Brigade, commanded by Brigadier Philip Hicks was ordered to hold the area because of the air landings that would take place there the next day.

German Response

Due to the vast scale of the air landings, they couldn't possibly remain unnoticed by the Germans. Local German commanders had no idea of the grand picture yet. At his headquarters in Hotel Tafelberg, Generalfeldmarschall Walter Model could think of only one reason why the Allies would land near Arnhem: his own presence. Therefore he wasted no time leaving his headquarters and went to Arnhem.[52] There he immediately went to see Feldkommandantur 642 in Villa Heselbergh, Generalmajor Friedrich Kussin who was in command of northern Arnhem. After having issued the necessary orders, Model drove on to Slangenburg Castle, Bittrich’s headquarters in Doetinchem. He arrived towards 15:00 with his Ia (chief of staff) General Hans Krebs. He immediately contacted Oberbefehlshaber West, Generalfeldmarschall Gerd von Rundstedt to arrange the necessary reinforcements. Subsequently he continued to Castle Wisch in Terborg, a little to the south, where his staff had established headquarters in the meantime.[53]

Well organized as the German high command was, the various reports were soon united in an overall picture and the Germans managed to reorganize in inimitable fashion with the troops they had at their disposal. Walter Model immediately placed II. SS-Panzerkorps under command of his Heeresgruppe B and divided the battlefield into three clear sectors. The southern sector entailed the area of advance of XXX Corps and the landing zones of 101st Airborne Division, the central sector around Groesbeek and Nijmegen and the northern sector Arnhem-Oosterbeek. Generaloberst Kurt Student was put in command of the southern sector and received the necessary reinforcements in the form of the 59. Infanterie-Division and Panzer-Brigade 107. The sector Nijmegen-Groesbeek was assigned to Wehrkreis VI, the center of gravity being Korps Feldt. It was reinforced by 406. Landesschützen-Infanterie-Division and parts of II. Fallschirmjäger-Korps. The sector Oosterbeek-Arnhem was assigned to Friedrich Christiansen who had Kampfgruppe Von Tettau and II. SS-Panzerkorps commanded by Wilhelm Bittrich at his disposal.

In the morning, Walter Harzer, at that moment in temporary command of 9. SS-Panzer-Division, was in Hoenderloo and two of his officers with the SS-Panzeraufklärungs-Abteilung 9 for the presentation of the Ritterkreuz to its commander, SS-Hauptsturmführer Viktor Gräbner who was to be awarded for his actions in Normandy. His whole unit had fallen in for the occasion. They all witnessed the British landings. The armored vehicles of the unit had already been loaded onto trains to be transferred to 10. SS-Panzer-Division. It was decided to cut the ceremony short and to start preparing the vehicles.[54] They would have to head for Velp immediately after which some of them would be directed to Nijmegen and another part to Oosterbeek.

In Brummen SS-Hauptsturmführer Hans Möller, commander of SS-Panzer-Pionier-Bataillon 9, had also been watching the landings. Realizing what was happening, he alerted his unit and made his way to headquarters of 9. SS-Panzer-Division.[55]

The commander of SS-Panzergrenadier-Ausbildungs und Ersatz-Bataillon 16, SS-Sturmbannführer Sepp Krafft saw the parachutists land nearby from his headquarters and didn't hesitate a second. At 12:30[56] he ordered his battallion to go on full alert. He merged his 2. and 4. Kompanie into Kampfgruppe Krafft (Bataillon Krafft). His third company, the 9th consisted of long-term patients and was still billeted in Coehoorn barracks in Arnhem.[57]

Sepp Krafft realized almost immediately that the target of the airborne troops would be the bridge at Arnhem and reacted accordingly to repulse this threat. Operating from Hotel Wolfheze, he deployed his troops in such a way that he could block almost any route from LZ-Z in the direction of Arnhem. He had a line established from the railway Wolfheze-Arnhem up to the Utrechtseweg, right along the routes that would be taken by Reconnaissance Squadron, 1st Parachute Battalion and 3rd Parachute Battalion. Krafft hoped to delay the advance to such an extent that troops around Arnhem had time to regroup. Around 15:30 his 9. Kompanie which had been transferred from Arnhem, was also put at his disposal.

Soon after the landings, headquarters of II. SS-Panzerkorps had put all its units on full alert through the adjutants of the divisions. At 16:00[58] SS-Obergruppenführer Wilhelm Bittrich issued an order to 9. SS-Panzer-Division to occupy Arnhem, pin the airlanding troops down on their positions and subsequently destroy them. 10. SS-Panzer-Division was to head for Nijmegen to establish a bridgehead over there and in so doing deny the enemy the approach to the northern bank of the Waal.