Introduction

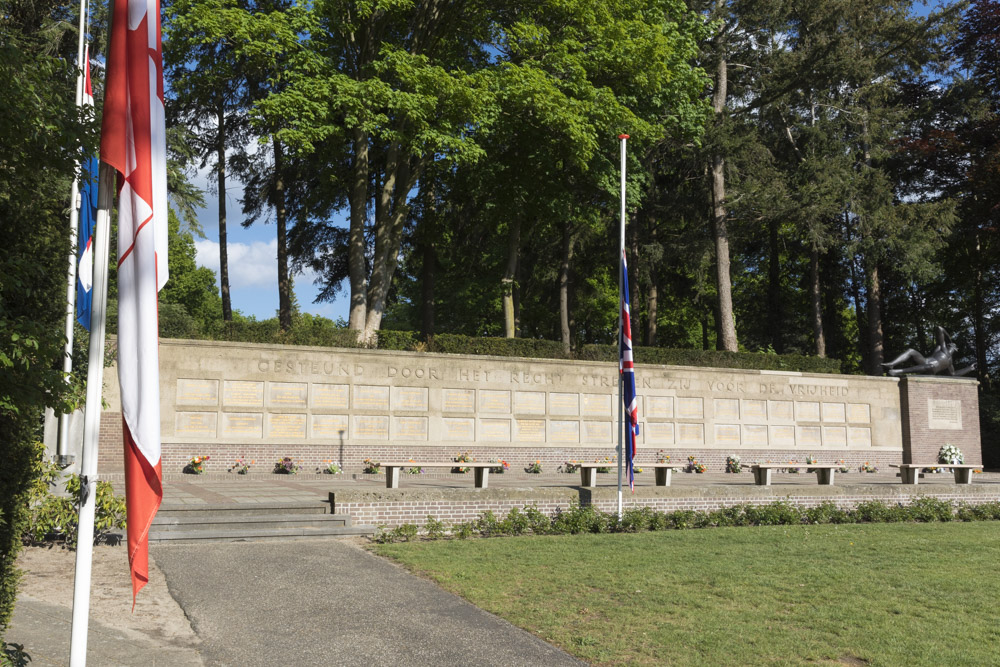

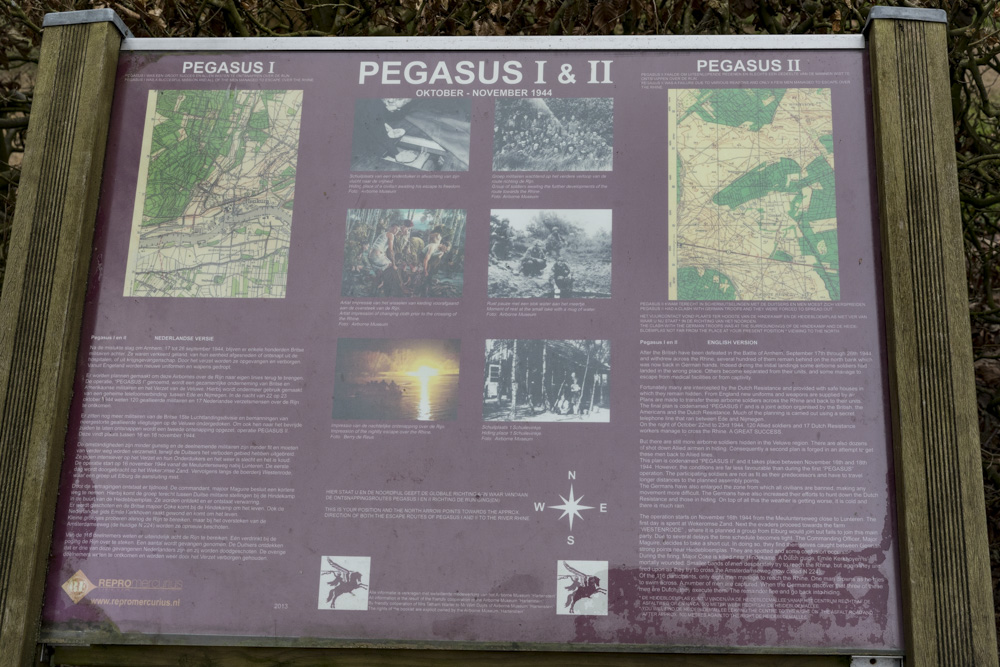

During World War II, Major Airey Neave was head of British Intelligence. He was responsible for providing opportunities for Allied soldiers to escape from occupied territory in Western Europe and therefore he was partly responsible for operations Pegasus 1 and 2. According to Neave, Operation Pegasus 1 was the largest escape from occupied territory during World War II.

In the night of 22nd to 23rd October 1944, a group of 130 troops (aircrew and paratroops) and 8 civilians proceeded to cross the river Rhine. During, as well as after World War II, there was much interest in this successful operation.

This is in contrast to the escape attempt about a month later, under the code name Pegasus 2. This operation failed entirely, for a number of reasons. Only a little above 100 Allied soldiers, who participated in this operation, safely reached the other side of the Rhine. Until a few years ago, there was very little known about this event but it is worthwhile to dig deeper.

Images

Insignia of the Britsh air borne troops: a blue Pegasus, ridden by Bellerophon, against a purple background Source: www.wikipedia.org.

Insignia of the Britsh air borne troops: a blue Pegasus, ridden by Bellerophon, against a purple background Source: www.wikipedia.org.Preparation

After the failure of Market Garden, Major Airey Neave worked in the Allied headquarters in Brussels on a second mass escape, intended to retrieve even more cut-off Allied troops and bring them back to their own lines. From stories of people, who were involved in Pegasus 1, he learned that there still were about 150 allied soldiers in occupied territory. For various reasons they had not been able to participate in Operation Pegasus 1, for example, the resistance group did not succeed in informing them in time about Pegasus 1.

For the purpose of preparation of Pegasus 2, Major Neave sent two people to occupied territory in order to assist the local resistance in the organization of the mission. In the night of October 17th,1944, Dutch Lieutenant Abraham du Bois and his Belgian Radio Officer Raymond Holvoet landed in the village of Garderen.

These two men had been chosen for this dangerous mission because they proved themselves to be skilled and courageous soldiers during actions in the past. Until his participation in Pegasus 2, Abraham du Bois (pseudonym: Martien) was one of the deputy commanders of the Princess Irene Brigade. He also served on the staff of Princess Juliana in Canada. During May 1940 as well as during operations to prepare for the Normandy invasion, he had shown great courage and skills.

Raymond Holvoet originated from the Belgian city of Kortrijk. He had performed several missions in occupied territory as a radio operator of a Belgian Special Air Service (SAS) unit. Every time after a mission, he succeeded in returning to England in one piece. However, a couple of days after the landing, on October 17th, 1944, he was arrested by the Germans. He was imprisoned in several places and on April 10th, 1945, on orders of the SD (Sicherheitsdienst or security service), he was shot near the IJssel bridge in Zwolle.After a few days, Martien was completely reliant on himself. Together with the local resistance he had to try to turn Pegasus 2 into a success. It was certain that this would be much more difficult than with Operation Pegasus 1.

During the previous operation, the local resistance was lucky enough to be able to combine the mass escape with the forced evacuation of the village of Bennekom. The Germans were unable to check the huge traffic flow, allowing the Allied troops to reach their meeting place unperceived.

The Germans, who were very angry about the fact that so many allies managed to escape on their watch, took drastic measures to prevent a second escape. They evacuated the northern bank of the Rhine over a distance of about 10 kilometres, where no civilians were allowed. A good reconnaissance of that area was therefore extremely hazardous. In addition, the distance to be covered between the meeting place and the crossing point was much larger than in Pegasus 1 on October 22nd. This meant that about 100 allied soldiers had to stay in the open air approximately for the duration of a day, which would increase the risk of being discovered by the Germans.

The intention of this operation was to cross the river Rhine at a different location. The choice had fallen on a spot near the Heterense Veer (ferry Heteren). By means of a telephone line of the resistance, Abraham du Bois had intensive consultations with the headquarters of the British Second Army in the already liberated city of Nijmegen. Headquarters ordered that the crossing should take place on the night of November 17th to November 18 th or the two following nights. During those three nights, everything would be ready for the mass escape on the south bank of the Rhine. From the north there would be three green light signals to prompt Canadian soldiers to go across the river with their storm boats to pick up the refugees. The British artillery would give cover fire to keep the Germans at a distance.

Definitielijst

- Brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Images

Raymond André Holvoet Source: www.specialforcesroh.com.

Raymond André Holvoet Source: www.specialforcesroh.com.Execution

The distance from the first meeting place to the transfer point was approximately 20 kilometres and so two days had been planned for the complete operation. On November 16th, the first groups made for the first meeting place, travelling through shortcuts. This meeting place consisted of a number of empty chicken coops behind the farmstead of family Wolfswinkel at the Meulunterse Way in Lunteren. On the evening of November 17th, 75 Allied soldiers and 5 guides gathered there.

Major Hughes Maguire, an intelligence officer of the 1st British Airborne Division, would take the lead of this trip. Abraham du Bois took care of the escape route and the distribution of weapons to the group. The distance from the meeting place to the crossing point at the Heterense Veer was far too great to cover in one night. Therefore the group was forced into hiding during the day in a forested area, skirting along the estate Wekeromse Zand. This was a very dangerous area, regularly patrolled by the Germans.

Against the orders of Du Bois, Maguire made his own plan. He himself would command the front group, escorted by only six armed soldiers. The front group would be followed by the main group, (consisting mostly of hospital soldiers and pilots) who had had hardly any ground combat training. The main group was led by the army doctors Allenby and Longland. The rearguard, better known as the fighting group, was headed by Major Julian Coke. The members of the rearguard carried 44 Sten guns with them. This uneven distribution was the result of Maguire’s vision: he wanted to reach the river without the use of weapons. In case the Allied escapers were pursued by the Germans, the defence would be in a position to restrain the Germans until the group could come within the firing range of the British artillery at the southern bank, who would then take over the protection by cover fire.

November 18th, at four o'clock in the morning, the whole procession left for the first part of the mass escape. After a difficult and wet march, the forested area near the Wekeromse Zand estate was reached without any problems. It was quite cold and therefore each participant was given a glass of rum in an effort to stay warm. Energy tablets had to be returned to the army doctors, so they could be administered to men who had become overtired. Abraham du Bois, who also participated in the first part of the march, announced that, in the course of the evening, about 20 Allied soldiers would join the group near Westerrode, north of Ede. Before Du Bois left the group, he emphasized again that they had to stay east of the village of Heibloem. If they would not do so, the group would pass too close to the German positions.

At five o'clock in the evening the escapers left the Wekeromse Zand with the objective of advancing to the river without intervals. Around nine o'clock in the evening, the group reached Westerrode, realizing then that they were already two hours behind schedule. Maguire had no time to keep waiting for the 20 soldiers, who would join the group, since he was afraid of reaching the river Rhine too late.

Under Maguire’s command, the group continued the escape route as mapped out by Du Bois. The speed was low because of stops which had to be made to prevent the Allied military from losing one another. After some time a discussion arose about a possible shorter route. One of the guides protested against the proposal, but Maguire persevered. At his command the group of escapers headed in the direction of the Heibloem. Doing so, they encountered a German artillery position consisting of two batteries with far distance canons where a very alert sentinel directly hit the alarm. On his call “Who’s there”, nobody responded and virtually nothing happened at all. Maguire decided to move on, but did not notice that only the front group was following him; the rest of the group was staying under cover.

Once they were at Heibloem, Maguire decided to perform a head count and came to the discovery that only 30 men were with him. In a clearing in the forest, the group took a rest, while Maguire went back to see where the rearguard was. Their commander, major Coke, was trying to find out where the front of the group had gone and so these two officers encountered each other. Maguire told him where the front group was and ordered him to join his stragglers within ten minutes. Maguire joined again at the forefront at Heibloem Avenue. After ten minutes of waiting in vain, Maguire moved on with his 30 men. The rearguard never got the message to join, since major Coke was killed by German fire on his way back to his group.

Meanwhile the vanguard reached the end of the Heibloem Avenue and in front of them was the road from Ede to Arnhem. That road seemed very quiet and no Germans were to be seen. However, when some of the Allied soldiers reached the other side of the road, heavy machine gun fire broke loose. The whole area was illuminated by star shells. The startled escapers panicked, fled in all directions and hid in the dense forest. The whole formation was lost and small groups either tried to advance separately or went into hiding. Only seven out of approximately 100 soldiers managed to make the crossing of the Rhine. About 30 men were captured and around 50 men managed to stay out of German hands.

Definitielijst

- machine gun

- Machine gun, an automatic heavy quick firearm.

Aftermath

For Abraham du Bois, Pegasus 2 also turned out to be a failure. At the end of November 1944 he came into contact with a Dutch SD (Sicherheitsdienst; security service) officer who he thought was on his side.. This officer was willing, in return for a large amount of money, to treat the wireless operator and friend of Du Bois, Raymond Holvoet, as a prisoner and not as a spy. For Holvoet, this would imply that he would remain in a prisoner of war camp until the end of the war and subsequently would have more chance to survive the war. Du Bois had to choose between his distrust of the German officer and the life of his friend that was in his hands. Despite warnings from members of the resistance, he made an agreement with this SD officer. This, so called officer however, was known as the notorious collaborator Johnny den Droog, who already had betrayed a lot of resistance members.

Driven by his great friendship for Holvoet, Du Bois could not resist the temptation of meeting the officer at the farmstead Wester Wetering near Ede. Supposedly it was to negotiate the price. Just as Du Bois entered the farm, the place was surrounded by Germans. Du Bois tried to escape through the back door, where he was shot in his leg with two bullets. He was arrested after a wild struggle. Although the resistance had made plans for his rescue, the Germans’ strict surveillance would make the rescue mission suicidal. On March 8th, 1945, Abraham du Bois, with many others, were executed at the Woeste Hoeve.

After the war, reasons for the failure of Operation Pegasus 2 were researched and discovered. The physical condition of the participants was not up to par for such an intense, nocturnal march. The long distance also played a part in it. Furthermore, they had made too much noise. Finally, it was unfavourable that Maguire took the lead: he deliberately deviated from Du Bois’ itinerary. He also changed the arrangement of the group, resulting in a situation in which giving cover fire in the fast possible way was impeded. In summary, due to the above mentioned unfortunate combination of several circumstances, Operation Pegasus 2 was considered a complete failure.

Definitielijst

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Images

Abraham du Bois Source: www.prinsesirenebrigade.nl.

Abraham du Bois Source: www.prinsesirenebrigade.nl.Information

- Translated by:

- Chrit Houben

- Published on:

- 17-10-2012

- Last edit on:

- 30-09-2024

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Related books

Sources

- MIDDLEBROOK, M., Arnhem, ooggetuigenverslagen van de slag om Arnhem, Kosmos Uitgevers B.V., Utrecht, 2010.

- NOORDMAN, W., Luchtalarm op de Veluwe, Kok, Kampen, 2002.

- PEELEN, TH. & VAN VLIET, A.L.J., Zwevend Naar de Dood, Vaan Holkema & Warendorf, Bussum, 1977.

- VEER, W. VAN DER, Operatie Pegasus, Uitgeverij J.H. Gottmer/H.J. Becht BV, Bloemendaal, 1994.