Introduction

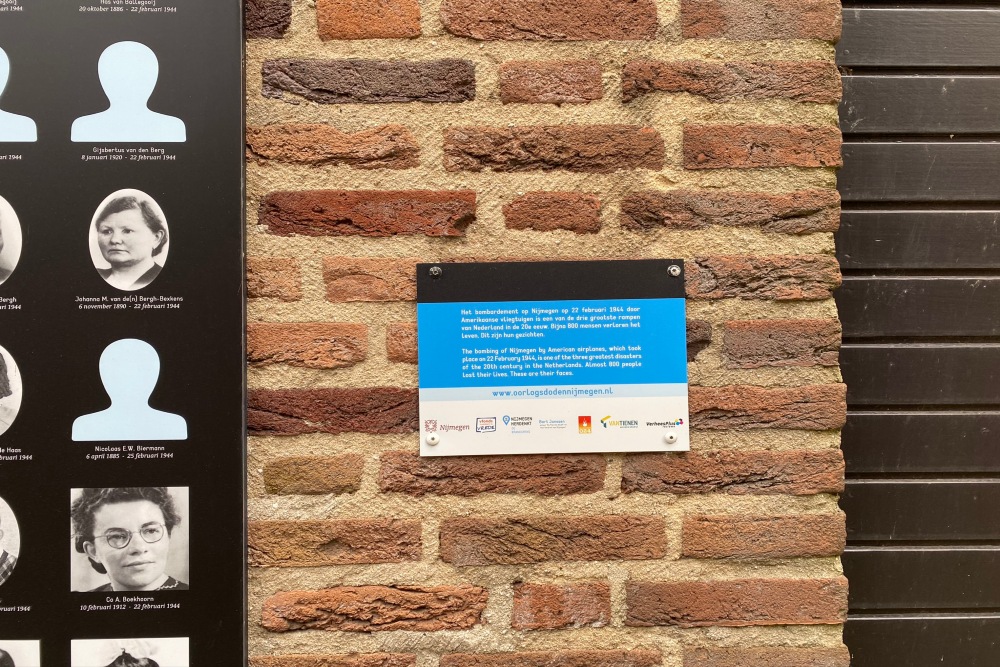

Almost every Dutch person is familiar with the German bombing of Rotterdam in May 1940. In order to force the capitulation of the Dutch army, in the afternoon of May 14th, the Germans bombed the city of Rotterdam, resulting in approximately 800 deaths. However, far fewer people will be familiar with the American aerial bombardment of Nijmegen on February 22nd,1944, although this attack resulted in the same number of casualties or maybe even more.

The bombing of Nijmegen has never received the attention it deserved. For a long time, it even remained unclear, how this bombing could have happened. The general hypothesis is that it was a mistake, but there are still people who are convinced that the bombing was carried out deliberately. This paper describes what went wrong on February 22nd, 1944, which led to the bombing of Nijmegen. (An editorial is a commentary/lead article by the chief editor) Also the effects of the bombing will be looked at in further detail.

Definitielijst

- capitulation

- Agreement between fighting parties concerning the surrender of a country or an army.

Images

German propaganda about the American bombardement of Nijmegen Source: Verzetsmuseum Amsterdam.

German propaganda about the American bombardement of Nijmegen Source: Verzetsmuseum Amsterdam.Operation Argument

In November 1943 the Allies developed a plan to carry out a large-scale air offensive against the German aircraft industry. Only through the destruction of the German Luftwaffe, the Allies could gain air supremacy, which they needed for the invasion of Europe’s mainland. The code name for this operation was "Argument". The idea was that for a week, every day massive air raids would be carried out at major centres of the German aircraft industry, such as Gotha, Leipzig, Tutow and Posen (now Poznan in Poland).

All American and British air forces in Europe: the U.S. 8th Air Force, stationed in England, the U.S. 15th Air Force, stationed in the Mediterranean and the Bomber Command of the Royal Air Force (RAF) would be deployed for this attack. The Allies bombed "Around the clock". The Americans at daytime and the British at night. This way the Germans would not have a single moment of rest and repair activities would be hampered.

For the implementation of this operation, however, a number of requirements had to be met. First the U.S. Air Force in Europe had to be reinforced with additional aircraft . Weather conditions would be an influencing factor to the offensive. The best conditions for the operation would be a clear sky above the targets to be attacked. Moreover, there were problems in the Allied high command. Lieutenant General Carl Andrew Spaatz (commander of the 8th and 15th U.S. Air Force) and the Supreme Allied Commander, Dwight Eisenhower, had a conflict about the strategy. Spaatz feared that Eisenhower would use the Air Force for the preparation of the Allied invasion, before the total air supremacy had been achieved.

Finally, on February 19th, 1944, the weather forecast was good enough for the launch of Operation Argument. Big Week, as the operation was called as well, began in the night of February 19th to 20th, with a massive attack on Leipzig by the RAF. The British suffered big losses. Eighty seven of the 734 aircraft did not return.

The goal of Operation Argument on Tuesday, February 22nd, 1944, was the Gothaer Wagon Fabrik AG, a major producer of the Messerschmitt BF 110, a German night fighter / fighter-bomber. The attack would be carried out by the 2nd Bombardment Division, commanded by Major General James Hodges (1894 - 1992). The 2nd Bombardment Division was divided into three Combat Bombardment Wings (Combat Wing): the 2nd, the 14th and 20th. The 20th Combat Bombardment Wing consisted of three Groups (Bomb Groups): the 93rd, 446th and 448th.

The 446th Bomb Group was established on April 1st, 1943, and was equipped with a heavy bomber of the type Army Consolidated B-24, better known as the "Liberator". Her base was Flixton Air Base in Bungay (Suffolk) . The first mission she flew on December 16th, 1943. Colonel Jacob J. Brogger was the commander since September 27th, 1943. The operations commander was Captain William A. Schmidt.

For the 446th Bomb Group, the "Big Week" began on Sunday, February 20th, 1944, with an attack on Gotha. The Wagon Fabrik was bombed, but whether and how severely the plant got damaged is unknown. On February 21st, an attack was carried out on the airport of Handorf in Niedersachsen. Most of the crew of the Bomb Group were relatively inexperienced, since none of them did have more than five missions on their records.

If, for whatever reason, the factory in Gotha could not be attacked on February 22nd, the bomb group had to divert to the airport of Eschwege in Hessen. If both targets appeared to be not achievable, then the attack should be aimed at: "Any military objective in Germany, preferably aerodromes."

Definitielijst

- Bomber Command

- RAF unit which controlled strategic and sometimes tactical bombing (as in Normandy)

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Luftwaffe

- German air force.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- RAF

- Royal Air Force. British air force

- strategy

- Art of warfare, the way in which war should be conducted in general.

Images

Heavy bombers, type Consolidated Army B-24, better known as the “Liberator” Source: U.S. Air Force.

Heavy bombers, type Consolidated Army B-24, better known as the “Liberator” Source: U.S. Air Force. Insignia of the American 446th Bomb Group Source: www.aviationmuseum.net.

Insignia of the American 446th Bomb Group Source: www.aviationmuseum.net.The attack

After the briefing was over, 37 aircraft of the 446th Bomb Group took off around 9:20 am, divided into three sections. The operation was severely hampered by bad weather. There was a very dense blanket of clouds and, due to a light snow storm, the visibility was sometimes limited to only 270 meters. When the aircraft reached the Dutch coast at about 12:25, the weather was getting better and vision became brighter. The American formation had to deal with attacks by German fighters and shelling by German Flak (anti-aircraft artillery). However this was not a major impediment to the 446th Bomb Group, especially since the German attack was mainly focused on the rear of the formation of the Combat Wing and the 446th flew in front.

Meanwhile, however, Major General Hodges, the commander of the 2nd Bombardment Division, received ominous reports about the situation on the English coast. Because of the bad weather (the dense clouds and strong winds), many aircraft lost contact with their original group. Complete sections were forced to return to base. This created an unclear situation. The formation of aircraft was being stretched, which made them very vulnerable to enemy attacks. Major General Hodges decided that it was irresponsible to continue the mission and gave a recall at 12:25 o’clock, a signal to terminate the mission.

Pilot Cole, commander of the second Section of the 446th Bomb Group, received the recall and passed it on to Captain William Schmidt, who flew as second pilot in one of the aircraft of the first section. Schmidt tried to have the headquarters confirm the message, but failed because he could get no connection. The failure of the radio connections was due to several reasons. Firstly, the radio reception was impaired by the snow storms that occurred over England. Also, in one of the aircraft, the transmitter of the radio installation got stuck, resulting in a constant radio transmission from the aircraft involved, which hindered the other aircraft in transmitting radio messages. Also bad communication between the aircraft and the headquarters could have been caused by "window" or "chaff", the aluminium foil trips that were dropped by the Allies to disturb the German radar.

Schmidt was unable to get into contact with headquarters in England, he had made contact with the commanders of the other Bomb Groups in the Combat Wing (the 93rd and 448th), through the high frequency radio, in order to ask whether they had received the recall. And, yes indeed, they did receive the recall. This was partly the reason why William Schmidt still decided to suspend the initial mission at 12:55 hours. However, at that moment, the Combat Wing was over Germany already. Therefore Schmidt ordered to look for an alternative opportunity target. The 446th Bomb Group did split up into the three original sections. A chaotic situation occurred. The 446th performed some difficult turns while there was a strong high wind of 90 knots . Next to that, some aircraft of the 446th had to turn away several times to avoid aircraft, that approached from another direction.

Two aircraft from the 453rd Bomb Group joined the first section of the 446th. These aircraft actually belonged to the 2nd Combat Wing, but they lost sight of their formation and therefore they joined the 446th Bomb Group, since it was safer to join a larger formation. While flying in a larger formation, the aircraft were able to cover each other far better with their on-board weapons in case of an attack. These two aircraft were armed with 80 cluster bombs.

Subsequently, the first section of the 446th Bomb Group carried out an attack on the German city of Goch in the vicinity of Kleef, the second section did not drop their bombload and the third section carried out an attack on Kleef . At least this is what Schmidt, later on, would report about the mission. Maybe, even during the attack, some crew members of the 446th Bomb Group noticed that they were above the Netherlands, but they followed the guiding aircraft of Schmidt and, whether or not accidentally, dropped their bombs at Nijmegen and Arnhem.

Definitielijst

- Flak

- Flieger-/Flugabwehrkanone. German anti-aircraft guns.

- radar

- English abbreviation meaning: Radio Detection And Ranging. System to detect the presence, distance, speed and direction of an object, such as ships and airplanes, using electromagnetic waves.

- shelling

- Indication for shooting targets with grenades. Both from artillery and armoured artillery.

Images

An Avro Lancaster dropst “window” or “chaff” (white spot at the left), strips of alu foil, which interfered the German radar, however, prior to the bpmbardment of Nijmegen, the allied radio communication as well Source: Imperial War Museum.

An Avro Lancaster dropst “window” or “chaff” (white spot at the left), strips of alu foil, which interfered the German radar, however, prior to the bpmbardment of Nijmegen, the allied radio communication as well Source: Imperial War Museum.The bombardment

The Americans intended to bomb the railway yard of the city of Nijmegen. The destruction or damaging of railways and adjoining facilities was an important opportunity target for the Allied air force, as this would cause big transport problems to the enemy. At the dropping of the bombs, Vere McCarty (the bombardier of the front plane of the first section) made a miscalculation. It was customary for the bombardiers to focus on the dropping zone of the front plane. McCarty was afraid that the other bombardiers would not take the high wind speed on the ground into account. For that reason, he had the bombs dropped on a building, at a few meters distance of the railway yard. However, the aircraft that flew behind dropped their load of bombs at the correct spot (exactly at the spot McCarty recommended ), or even too early, resulting in a direct hit of the centre of Nijmegen instead of at the railway yard.

At 12:14 hours in Nijmegen the air-raid warning sounded to warn the citizens about an air attack. Hundreds of bombers flew over Nijmegen, on their way to Germany. At 13:16 hours the safety signal was on, indicating that, according to the Air raid Protection Department (LBD), the danger was over. All of a sudden, a LBD sentry noticed that a number of aircraft approached from the east. A few minutes later (at 13:28 hours) bombs were dropped. A new air-raid warning came too late, partly due to the fact that such a signal could only be issued if the Germans had granted permission to do so. Due to this, hundreds of people were out on the streets during the air attack.

As mentioned earlier, a large number of bombs did hit the centre. The shops V&D [ a kind of Marks & Spencers] and Hema [a large dime-shop], at the Grote Markt, were among the first buildings which were hit. Fortunately, only few people were in the shops at that very moment. However, the Germans had requisitioned a part of the V&D building for the Deutsche Feldpost, the post office of the German Wehrmacht. In this post office, thirty people were killed. At the same time when the V&D building was hit, the Saint Stevens Tower (originating from the 13th century) got hit as well. The tower collapsed, killing five employees of the LBD, who used the tower as a watch tower. Additionally, due to the tower, falling on top of several blocks of houses, dozens of people on the ground were killed.

On the Lange Burchtstraat, the primary Montessori school of the Sisters of Jesus Maria Josef got hit by several bombs, killing eight sisters and twenty four children. Other streets in the city that were hit: the Houtstraat, Bloemerstraat, Doddendaal, Oude Varkensmarkt, Parkdwarsstraat, Achter Valburg, Stikke Hezelstraat and the Krayenhofflaan.

Especially the bombs of the 453rd Bomb Group claimed many victims. The 12 aircraft of the 446th Bomb Group were each equipped with twelve 500 lbs high explosive bombs. These bombs were specifically manufactured to cause damage by destroying buildings and other infrastructure. The aircraft of the 453rd Bomb Group were each equipped with 40 HNM41 cluster bombs. Each of these bombs consisted of six smaller, twenty pound, bombs. The moment these bombs exploded, they spread a cloud of shrapnel. Such bombs were not intended to destroy, but they were meant to kill personnel. Nine cluster bombs remained in one of the aircraft, so, a total number of 71 of these bombs fell on the city. This makes a total of 426 deadly cluster bombs, which hit Nijmegen.

Some of the bombs landed on the Valkhof and Kelfkensbos (street in the city centre), which resulted in thirty-five deaths and numerous injured. One of the firefighters who arrived at the spot, described the situation as follows: "Corpses, grey of dust, mixed with blood. Grey, everything is grey. God, what a dust! Emergency services, stretchers, people running around. Desperate faces".

The other part of the cluster bombs landed on the crowded Stationsplein [railway station square]. At that very moment, a tram and bus were waiting for departure, both loaded with passengers. Both vehicles were hit by the rain of bomsplinters. Eighty people met their death on this square.

Definitielijst

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Images

Aerial picture of Nijmegen during the bombardment. In the centre, explosions of bombs are visible Source: Beeldbank WO2.

Aerial picture of Nijmegen during the bombardment. In the centre, explosions of bombs are visible Source: Beeldbank WO2. Destroyed city centre Source: Beeldbank WO2.

Destroyed city centre Source: Beeldbank WO2. Ruins of the St. Stevenstoren Source: Beeldbank WO2.

Ruins of the St. Stevenstoren Source: Beeldbank WO2. Devastations in the Houtstraat Source: Beeldbank WO2.

Devastations in the Houtstraat Source: Beeldbank WO2. Stationsplein with burnt out tram-car Source: Beeldbank WO2.

Stationsplein with burnt out tram-car Source: Beeldbank WO2.Fire and rescue

Due to the tapestry of bombs, several houses in the city caught fire. As a result of dry weather and moderate wind, the fire spread rapidly. The heaters and paraffin stoves, which were largely present in the city, contributed to the start of a massive conflagration. Extinguishing the fire was severely hampered, because of the fact that the water supply was destroyed at several places in the city. A major part of Nijmegen was without water. Dozens of people, who actually survived the bombing, but got trapped under debris of collapsed houses, now got killed by the fire. In the absence of water pressure the fire fighters had to pump water, among others, out of the river Waal. However, this was a time-consuming method. Next to that, the Nijmegen fire fighters had to contend with a shortage of equipment. Partly because of these circumstances, the fire in the city lasted for days.

Initially, the relief work was progressing slowly, which was partly due to the fact that the telephone operator at the police headquarters had been killed during the bombardment. This caused complicated communications at the beginning, which hampered the rescue activities.

The hospitals in Nijmegen could not cope with the hundreds of injured people. This necessitated the establishment of several first-aid posts in, among others, the building of the Twentsche Bank at the Mariënburg and in the Convent school at the Biezenstraat. Also some emergency hospitals were set up, including in the Internaat Klokkenberg. The attack caused more than 300 seriously injured and hundreds of slightly injured people. The number of serious injuries was less than the number of dead. Most likely this was due to the fact that many injured lost their lives during the fire.

The hundreds of people, that were killed as a result of the attack, were taken to the empty auction building on Vondelstraat. The identification proceeded laboriously, because many bodies were badly burned. Still, some deceased could be identified by showing personal belongings to possible next of kin. Nijmegen itself only had fifteen coffins in stock, so one had to call on other cities for extra coffins. Not every victim had his own coffin. Thus, the nineteen people, who got killed in the clothing shop W.G. Haspels at Lange Burchtstraat, were buried in seven coffins.

From an organizational point of view it was impossible to bury more than seven hundred dead separately. Therefore it was decided to inter the dead in common graves at the cemetery at the Graafseweg. There was a collective funeral ceremony for all the victims, which took place in the great hall of the Vereeniging, on Saturday, February 26th, 1944. The ceremony was quite unique because it was organized by civilians and any religious symbolism was not represented. The reason for the absence of religious symbolism was to avoid the choice between a Catholic or a Protestant service. At the cemetery itself, however, both the priest and the vicar were given the opportunity to address those present and to carry out their respective religious ceremonies.

Images

The city centre in fire Source: Beeldbank WO2.

The city centre in fire Source: Beeldbank WO2. Extinguishing the fire after the bombardment Source: Beeldbank WO2.

Extinguishing the fire after the bombardment Source: Beeldbank WO2. Funeral procession in Nijmegen on February 26th, 1944 Source: Beeldbank WO2.

Funeral procession in Nijmegen on February 26th, 1944 Source: Beeldbank WO2. Funeral of the victims on February 26th,1944 Source: Beeldbank WO2.

Funeral of the victims on February 26th,1944 Source: Beeldbank WO2.Review of the bombing mission

After the mission, the flight crew was interrogated by intelligence officers. These interrogations by the so-called S-2-officers were always conducted after a mission in order to acquire as much military information as possible. The bombed target also came up for discussion, of course. Seven out of the twelve interviewed men, were certain of their target: "Nijmegen". None of these first reports refer to the German city of Goch or Kleef. These cities only were mentioned in Captain William Schmidt’s report about the mission. This report is dated February 22nd, but Schmidt probably had it drawn up only a few days later, when it became clear that Nijmegen should not have been bombed. This report does not correspond with the statement he gave to Colonel Jack Wood, the commander of the 20th Combat Wing, during the review of the mission, in which Schmidt stated: “Finally found a city which we thought was in Germany, Nijmegen, and two sections dropped on it.” (Actually only one section bombed the city)

It is unclear whether Schmidt really thought Nijmegen was in Germany, or that he stated this in order to cover up his mistake. Some crew members really were surprised, when they learned that the city of Nijmegen was not a German city. It was not until Wednesday, February 23rd, when the crew realized that they should not have bombed Nijmegen. When the aircraft landed at Flixton, the men probably thought that they had carried out an attack on a legitimate opportunity target. Only later on they had been informed that they should not have bombed Nijmegen. According to U.S. sources, during the briefings prior to the missions, it regularly had been emphasized that it was not allowed to attack cities in occupied territory without permission. However, it remains unclear whether this really has been emphasized at the briefings so often and that all crews were well aware of this rule. Especially the status of Dutch cities was vague. Some Allied pilots even thought that Dutch cities were situated in neutral, instead of occupied territory. In 1944 two per cent of all Allied bombs were dropped over the Netherlands. On February 22nd, next to Nijmegen, Arnhem and Enschede were bombed as well, resulting in respectively 57 and 40 deaths.

On Tuesday, February 22nd, 1944, the American bombers considered a city with a railroad yard as a reasonable opportunity target. It is difficult to estimate whether they knew that this was a Dutch city before they attacked. The turning back after the recall, the disorientation this caused and the necessity to avoid collisions were to be blamed for much of the confusion of these crews with their limited experience. Shortly after the attack they already knew that they had bombed a Dutch city. They were however not yet aware of the fact that they had made a mistake. They did not realize that they had made a mistake, because the status of targets in the occupied territory was not sufficiently clear for them. The bombing was not intentional, but in fact it was not a mistake either. The commander of the 2nd Bombardment Division James Hodges, probably judged it correctly by considering it as a "faux pas" (a gaffe).

After the bombing and memorial

As a result of the attack, hundreds of buildings were destroyed and thousands of inhabitants of Nijmegen were left homeless. The official number of deaths by the bombing was 772. Most likely this number is underestimated, because, as a result of the fire, various bodies were completely carbonized. Also is it not clear how the situation was with the people in hiding in Nijmegen. There was a certain number, but it is unclear how many of them got killed.

The Germans tried to make propaganda with the U.S. air raid on Nijmegen. They distributed posters of the ruined city with texts like: "Van je vrienden moet je het hebben (You are well off with your friends)" This propaganda had little or no result. When Nijmegen was liberated in September 1944, the Americans were welcomed cheerfully, like in the rest of the Netherlands.

It took a long time before an official monument was established for the victims of the bombing. After the war the priority for reconstructions prevailed in Nijmegen. A big part of the city had been destroyed by the bombardment and during the battles of Operation Market Garden and the ensuing period, when Nijmegen found itself in the front lines during five months. Nijmegen had to be rebuilt and it would become more beautiful and better. The attitude at that time was “look ahead and do not complain too much". The municipality was of the opinion that commemorations should be organized by the civil population and thus they deployed little initiative for that. An influencing fact was that the city was bombed by an ally, and therefore it was a sensitive subject to raise.

From the 60’s the interest in World War II in Nijmegen started to slacken. In that time, there were only few commemorations in the city. Only at the end of the 20th century, interest in World War II increased again and the demand for a monument for the victims of the bombing of February 22nd, 1944, grew stronger.

This monument was created in 2000 and was placed on the Raadhuishof, at that time the location where the Montessori school was located, in which 24 children and 8 sisters had been killed. It represents a four-meter high swing. Also an annual official commemoration of the victims of February 22nd, 1944, was established in 2000.

The disaster of Nijmegen has not been included in the Dutch collective memory. However, the number of deaths by the bombing certainly justifies it. Therefore, it is correct that the bombing receives increasing attention, especially in recent years.

In 2005, a memorial stone was unveiled at the General Cemetery at the Graafseweg, the place where all the victims of the bombing are buried. The memorial contains a poem of the poet H.H. (Harry) ter Balkt: "The sadness fell down on the city, heart cutting grieve for the heart and the soul and the time of the city; fire spoke in tongues to the seven hundreds and to the persons killed after the stroke of the ax: 'Now your time is no longer with you’. Empty, the dragon chariots flew away from our friends, mourning grey and yellow light fell down after the raid, extinguished for ever as it seemed, silenced".

Definitielijst

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

Images

German propaganda poster, which was published three days after the bombardment Source: Verzetsmuseum Amsterdam.

German propaganda poster, which was published three days after the bombardment Source: Verzetsmuseum Amsterdam. Polygoon news about the bombardment Source: You Tube.

Polygoon news about the bombardment Source: You Tube. The monument on the Raadhuishof, the location where the Montessori school was settled and where 24 children and 8 sisters lost their lives Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The monument on the Raadhuishof, the location where the Montessori school was settled and where 24 children and 8 sisters lost their lives Source: Wikimedia Commons. Memorial at the Algemene Begraafplaats at the Graafseweg Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Memorial at the Algemene Begraafplaats at the Graafseweg Source: Wikimedia Commons.Information

- Article by:

- Wesley Dankers

- Translated by:

- Chrit Houben

- Published on:

- 21-09-2012

- Last edit on:

- 30-09-2024

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Sources

- BRINKHUIS, A., De fatale aanval, De Gooise Uitgeverij, Weesp, 1984.

- ROSENDAAL, J., Nijmegen '44, Vantilt, Nijmegen, 2009.

- Boom, B., Nijmegen 1944. Verwoesting, verdriet en verwerking, Historisch Nieuwsblad, nr. 4/2009, op: www.historischnieuwsblad.nl

- Brussel, S. van, Bombardement van Nijmegen, Geschiedenis 24 Andere Tijden, 20 januari 2004, op: www.geschiedenis24.nl/andere-tijden

- Jaspers, R., Bombardement geen vergissing, wel een 'faux pas', de Gelderlander, 21 februari 2009 , op: www.gelderlander.nl

- Namenlijst van slachtoffers van het bombardement van 22 februari '44, op: www.noviomagus.nl

- nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bombardement_op_Nijmegen

- www.446bg.com