History until 1940

Pre-war history

Fort Breendonk owes its existence to the strategic importance of Antwerp in the 19th century. Antwerp was developed into a "national redoubt", a kind of fortress, in which the government and other prominent people were able to hide from an enemy attack. For this purpose, a belt of forts was established around the city. At the beginning of the 20th century the construction of eleven new forts started, including Breendonk. In 1909, the construction of that fort began. Around the concrete buildings, a wide canal was created and the earth that came out of the canal, covered the buildings. At the entrance, a partly wooden drawbridge was made over the canal. In 1913, the first American soldiers moved into the fort. A year later, the Germans invaded Belgium for the first time. They did not immediately attack the redoubt, but guarded it with limited troops, while the main troops headed for France. Only when the offensive faltered did they focus on Antwerp. Just like other forts, Breendonk was not able to withstand the German shelling. On October 8th, a day after King Albert I had left the national redoubt, Breendonk surrendered. After the First World War, the fort did not play a significant role. It was only sporadically used during the interbellum.

May 1940

That situation changed in May 1940. Despite the Belgian neutrality, German troops invaded Belgium for the second time in thirty years. Fort Breendonk was declared as general headquarters for the Belgian army. King Leopold III and his general staff installed themselves in the fort. At night, he retreated into the nearby Château Melis. Initially, the atmosphere in the fort was optimistic but that changed very soon. The German armies seemed unstoppable and forced breakthrough after breakthrough. For that reason the general headquarters moved to Saint-Denis-Westrem on May 17 th. By then the fort was already in the frontline.

On May 28th, 1940, Belgium was defeated and Leopold III had no other option than to sign the surrender. For the Belgians, the war was over; even permanently in the eyes of many. Belgium was militarily governed by General Alexander von Falkenhausen. After the military, the Geheime Feldpolizei (GFP), the Sicherheitspolizei and the Sicherheitsdienst (Sipo-SD), with the Gestapo, settled in Belgium. The latter group turned Breendonk into the notorious Auffanglager.

Definitielijst

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

- interbellum

- “Latin: Between war”. Years between the Great War and World War 2.

- neutrality

- Impartiality, absence of decided views, the state of not supporting or helping either side in a conflict.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- shelling

- Indication for shooting targets with grenades. Both from artillery and armoured artillery.

- Sipo

- ”Sicherheitspolizei”. Combination (since 1936) of the Gestapo and criminal police.

Images

Auffanglager Breendonk

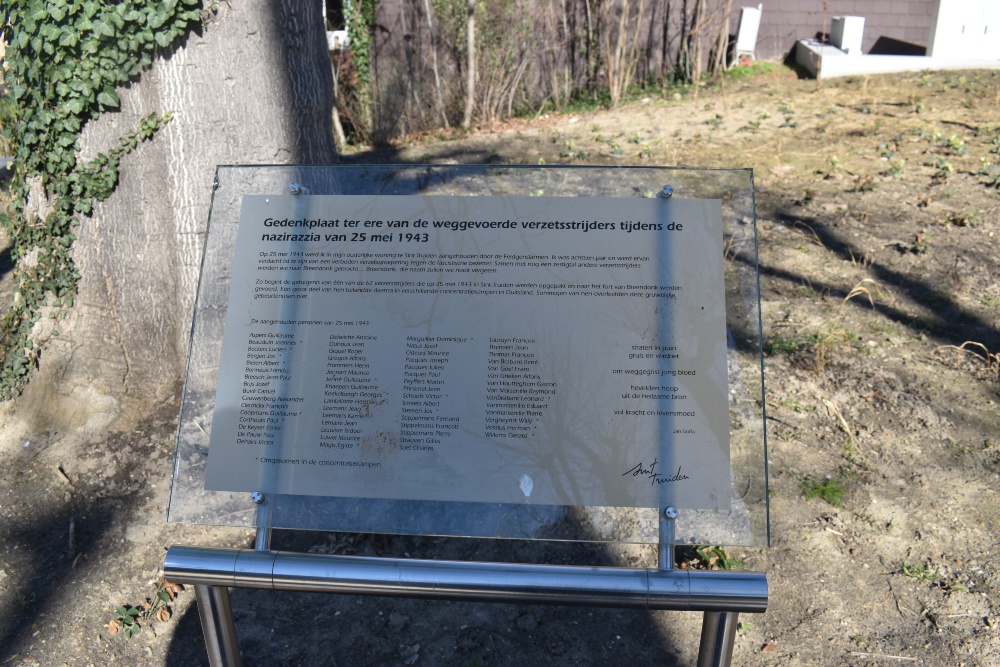

The choice for Breendonk as Auffanglager can be explained for several reasons. In the first place, facilities and space were available. Other camps often made use of existing infrastructure as well. For example, Auschwitz was based on a Polish army camp. Another important factor was the suitable location of the fort, which was situated halfway between the capital of Brussels and the important port of Antwerp. Moreover, 90% of the Belgian Jews lived in these two cities.

In late August 1940 the fort was put into use. The camp served as Auffanglager. This meant that prisoners were accommodated here, pending their deportation to other prisons or concentration camps. SS-Sturmbannführer Philipp Schmitt was in command. For the daily supervision of the prisoners, he especially depended on SS-Untersturmführer Arthur Prauss, who, together with 33 men of the Landesschutzbatallion from Mechelen, assured the guarding of the camp. Prauss turned out to be one of the greatest sadists of the camp. As from September 1941, Belgian SS members participated in guarding the camp. They had to provide more discipline.

On September 20th, 1940, the first prisoners were imprisoned in Breendonk. Three Jews and a Belgian political prisoner were the first of around 3600 victims, who were incarcerated in Breendonk for a short or longer period of time. Initially, Jews were also sent to Breendonk pending the establishment of the Dossin barracks in Mechelen as transit camp and as a gathering place for the Belgian Jews. In total, about five hundred Jews were imprisoned in Breendonk. The other prisoners were imprisoned there because of their accidental presence at a raid, their political opinions, their role on the black market or in acts of resistance, as a hostage, as a patriot and so on.

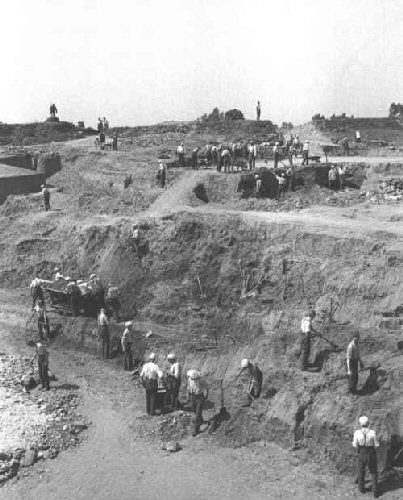

The first weeks, the number of inmates remained limited. However, they were put to work immediately. Their task was to dig up the huge layer of earth, which covered the fort. This way, space would be created for two large places for the roll-call. Gradually, more and more people were imprisoned in Breendonk. In January 1941, for the very first time, there were more than a hundred prisoners present. In the same period the regime in the camp became tougher: rations were limited, the work rate was increased and guarding became stricter. This led to the assignment of prisoners as house captains. These “Kapos" often abused their position in order to make their own situation more bearable. The fact that this happened at the expense of fellow prisoners, did not concern them. On February 17th, all boundries were exceeded: regrettably, for the first time there was a death in the camp.

Until June 1941, Jews formed a major part of the prisoners in Breendonk. From June 22nd this situation changed. After Operation Barbarossa, more and more communists and extreme leftists ended up in the camp. The number of prisoners doubled in a few months. The number of deaths increased as well (10 in July and August). In September 1942, the first prisoners were deported to Neuengamme in the neighbourhood of Hamburg because the construction of additional beds offered no solution for the lack of space. This would now become a general rule: when the camp was likely to be overcrowded, prisoners would be deported.

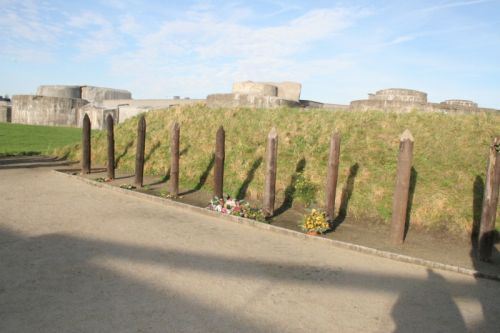

At the end of 1941, camp life slightly improved on impulse of the Militärverwaltung (the military administration of Belgium) camp life slightly improved, however, a year later new radicalization occurred that involved changes to the layout of the camp. Due to the fact that more and more members of organized resistance movements were imprisoned in Breendonk, cell blocks were built with isolation cells. A torture chamber and execution grounds were established, where, on November 27th, 1942, the first prisoners were executed. Torture and execution were now part of camp life. As mentioned, the camp regime became more disciplined: in particular the Flemish SS Wyss and De Bodt attracted negative attention by the massive abuse of the (mostly Jewish) interned. The harsh winter of 1942, together with the prohibition on distributing food packages, resulted in about forty deaths.

The number of Jews in the camp now systematically decreased. They were now collected in the Dossin barracks in Mechelen. Instead of Jews, Breendonk increasingly housed Belgian resistance fighters. Among them was Marcel Louette, the man behind the White Brigade - Fidelio.

During 1943 the infrastructure in Breendonk was expanded with new barracks, a toilet room and infirmary. After the vanishment of Schmitt as camp commander, life improved slightly in Breendonk. When finally, in June 1944, the Allies landed, the camp was systematically evacuated. So many prisoners were deported to Buchenwald that the first allied troops discovered a "virgin" Breendonk: no prisoners, no SS, no execution poles. Nothing at all would suggest what happened behind the thick walls during the war years.

Unfortunately this is not the end of the hell of Belgium. In the first days after the liberation of the fort, German prisoners of war, in particular, were incarcerated in the fort. In addition, even more collaborators and other (suspected) allies of the Germans came in the camp. Breendonk experienced its second horrendous period.

Definitielijst

- Brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Images

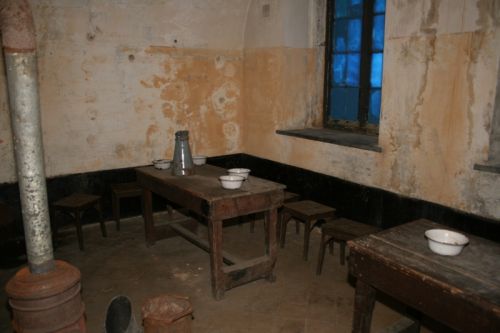

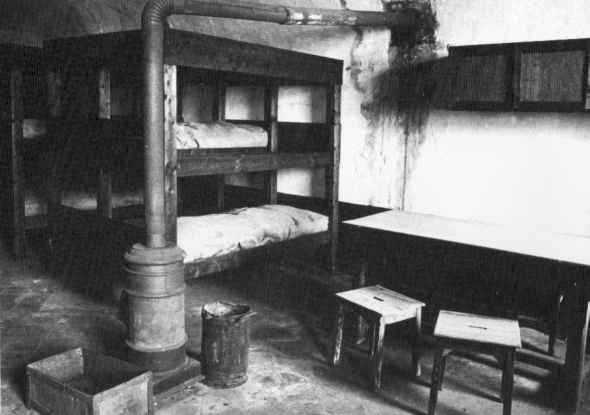

The rooms in which the prisoners were accomodated Source: Fort van breendonk.

The rooms in which the prisoners were accomodated Source: Fort van breendonk.Daily life

The first guards of the Auffanglager were not SS or combat troops. They were elderly soldiers who were assigned to surveillance operations. Although the SS was in command, life in Breendonk was still bearable at that time. The SS Prauss treated the prisoners very strictly, but the situation really deteriorated in September 1941, when the first Flemish SS members “paid their dues”. They had to ensure that disciplinary and discipline in the camp were strengthened. Some of the Flemish SS were soon notorious for their brutalities.

What did a day in the camp look like? Usually they arose around half past five or six o’clock. Next, the prisoners had a small amount of time to dress, wash and go to the toilet. Then Bettenbau followed, a principle that was applied in all concentration and extermination camps. The one whose "bed", which often was no more than a bag of old straw, was not properly made, received the first blows of the day. The breakfast consisted of two cups of "coffee" and a little bread. This was the base for a day of hard working. At noon, a little watery soup was distributed, in which the amount of vegetables, potatoes and meat decreased from day to day, while in the evening a small amount of bread was distributed. Spreads like marmalade or butter were rare. Thus hunger was present all the time. The combination with the hard work led to the deaths of many prisoners. Only in the last year of the war an improvement was noticeable: the Tehuis Leopold III was allowed to take care of the food supply, which made the rations increase significantly. However, for many prisoners this improvement came too late.

Despite the lack of food, the inhabitants of Breendonk had to do hard labour, which started around half past six. First, a barbed wire was built, surrounding the camp. Next the huge layer of earth, which covered the buildings and the future roll-call area, would be dug away. Later on, other assignments would follow, including the straightening of the canal and the strengthening of the banks with stones. The one and only purpose of this all was to tire out the prisoners: the work itself was completely senseless and had no economic benefit at all. The equipment consisted of no more than shovels, pickaxes, unwieldy wheelbarrows and heavy dumping carts. As if the work was not yet difficult enough, the SS were there to drain the prisoners even more: they could never go fast enough. Those who could not keep up with the pace, were exhorted with strokes and kicks to work even faster. This led regularly to work accidents: derailing dumping carts, badly injuring the workers. The Flemish SS, especially, liked to organize competitions among the prisoners: they not only increased the pace of work, but they also would beat up every one who could not keep up with the pace.

In between, roll-calls were held during which the prisoners not only were counted, but also were intimidated. The slightest "offence" was enough to get kicked and beaten. The main concern of the Breendonk prisoner was making it to the end of the day.

However, not all workers had the same tough life. The lucky ones were allowed to work in the carpentry, the tailors or shoemakers workshop. The work was considerably less hard and often they had certain privileges. This allowed the carpenters to walk freely through the camp with their toolbox to do some odd jobs. They used this opportunity to pick up cigarette stubs, which actually was strictly forbidden. Also, they could help other prisoners by slipping some small pieces of wood in their hands for the stove in their room. However, these jobs were limited and only destined for the "lucky" few.

Images

Suffering in Breendonk

As if the work had not caused enough suffering, prisoners were also tortured and murdered. The moment one arrived in Breendonk, the verbal and physical violence began. They constant shouted at and frightened the prisoners, undermining their mental defenses. In addition many punches and kicks were thrown. Julius Nathan was the first prisoner who died due to the heavy regime, Moses Loft was the first prisoner that was shot during a so-called attempt to escape. With these first deaths, a line was crossed, since then more and more lives were lost in Breendonk.

Yet in the early period of Breendonk the violence was moderate. Apart from the brutality and violence of the SS Arthur Prauss and the Jewish Kapo, Walther Abler, there was no talk of systematic maltreatment of the prisoners.

The situation changed in September 1941, when the first Flemish SS entered service. Some of them would become the most violent guards. Especially Fernando Wyss and Richard Debut were soon notorious for their brutality. Moreover, in the spring of 1942, a former storeroom was changed into a torture room. Mainly it was political prisoners and resistance fighters, who were interrogated by the Gestapo. The SS guards also were eager to use the torture room where they did not avoid to use various kinds of torture: thumbscrews, head clamps with lead balls, whippings and cigarette stubs. One of the worst tortures was the use of a pulley and wooden wedges. By means of a pulley and a hook the prisoner was pulled upwards, by his hands, which were tied behind his back. The weight of the prisoner himself caused a dislocation of the arms and shoulders. In addition the prisoner got whipped and was lowered in such a blunt way, that his knees and shins hit against the hard wooden wedges under the pulley. The torture only led to death a few times, but the prisoners were both mentally and physically scarred.

At the end of 1942 an execution site was created in a corner of the camp. Besides a number of wooden posts the guards also set up a gallows. This was a response to the ever murderous actions of the armed resistance. The first executions took place in November 1942 as a reprisal for the murder of the Rexistic (fascist political movement in Belgium) mayor of Charleroi Jean Toughens. A total of around 165 people were shot and 25 were hanged.

The result of four years Breendonk is deplorable: September 20th, 1940, up to and including August 31st, 1944, approximately 3,457 prisoners were incarcerated. At least 486 did not survive the hell of Breendonk, including 300 as a result of hardship or abuse. The others were executed. In the same period at least 440 prisoners were released. About 2,500 were deported to other concentration camps, of which at least 1,600 did not survive.

Definitielijst

- Kapo

- A Kapo was a prisoner in a concentration camp in Nazi Germany during World War 2 who was assigned to supervise other prisoners. A Kapo had to supervise the work of the prisoners and was responsible for their results on behalf of the SS.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Images

The torturers and their trials

After the surrender of Germany on May 8th, 1945, the first ex-prisoners of Breendonk returned home. With their home-coming, the horrifying secrets of Breendonk were revealed. The SS guards, who fled in September 1944, were tracked down. They were arrested one by one. Talking about all guards now would be too much for one essay. Therefore I restrict myself to the most important and prominent persons.

On September 20th, 1945, camp commander Philipp Schmitt was recognized by a former prisoner of Breendonk in the prison at the Noordsingel in Rotterdam. It was because of this former prisoner, that Schmitt was transferred to Belgium and imprisoned in Breendonk. It was not until August 1949 that he appeared in court because Belgian law did not allow the trial of German soldiers. Schmitt, however, could not escape his trial. He was held responsible for the Breendonk killings under his regime and was sentenced to death. On August 9th, 1950, a platoon of state police officers executed the dreaded Breendonk camp commander in the former Belgian military bakery in Hoboken. In Belgium, he was the only German Nazi who was convicted of war crimes and subsequently executed.

The second camp commander, Karl Schönwetter, fared better. He surrendered to the Americans in Braunau (Austria). He spent two years in captivity in Austria, but for one reason or another, he was never extradited to Belgium. In 1947 he was released. Schönwetter even married for the third time and seemed to escape from any prosecution. However, in 1968 the German court of justice opened an investigation but in 1975 further prosecution was relinquished because the research expanded in such a way that Schönwetter, who was not guilty of murder or manslaughter, was no longer a priority. He passed away on February 20th, 1976, in Witten.

Two of the most brutal members of the SS, Arthur Prauss and Johann Kantschuster (also wanted for war crimes at Dachau and Mauthausen), (probably) escaped from their punishment. The court failed to locate them after 1945. Prauss was probably killed in the battle for Berlin, while any trace of Kantschuster was lacking. In any case, both played at least an active role in the deaths of many prisoners in Breendonk.

The Belgian SS were dealt with as well. They were court-martialled in March 1946 in Mechelen. After more than five weeks, on May 7th, 1946, the sentence was pronounced . Heavy penalties were given to those who had committed serious crimes.

Fernand Wyss and Richard Debodt (who managed to stay out of the grip of the court) had been guilty of murder and manslaughter. Wyss had at least sixteen deaths on his conscience and abused dozens of other prisoners. He was therefore sentenced to death on April 12th, 1947, and shot without military honours (facing the pole). Debodt, was sentenced to death by default (he was arrested four years later). After a short trial in 1951, the court-martial affirmed the sentence. As a result of a decision by the Minister of Justice, Pholien, the punishment was converted to life imprisonment. Pholien had to resign under a storm of protest had, but the penalty was retained. Richard Debodt died on January 3rd, 1975, in the prison of St. Gillis.

Another six Belgian SS (Brusselaers, De Saffel, Lampaert, Pellemans, Vermeulen, Raes) were sentenced to death and executed on April 12th, 1947.

Also three room captains (Kapo’s: Obler, Lewin and Hermans) were guilty of murder and manslaughter and underwent the same punishment. In addition, two civilian workers, Van Praet and Carleer were sentenced to death because they had betrayed some prisoners, which lead to their deaths.

Definitielijst

- Kapo

- A Kapo was a prisoner in a concentration camp in Nazi Germany during World War 2 who was assigned to supervise other prisoners. A Kapo had to supervise the work of the prisoners and was responsible for their results on behalf of the SS.

- Mauthausen

- Place in Austria where the Nazi’s established a concentration camp from 1938 to 1945.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- war crimes

- Crimes committed in wartime. Often concerning crimes committed by soldiers against civilians.

Images

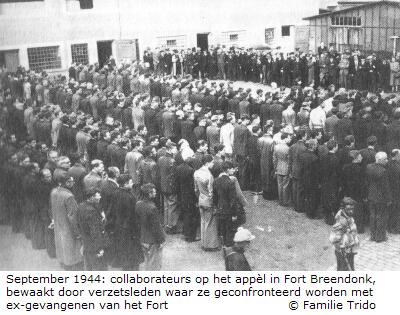

The trial of the Flemish SS guards in Mechelen Source: Gazet van Antwerpen.

The trial of the Flemish SS guards in Mechelen Source: Gazet van Antwerpen. The trial of Flemish SS in Mechelen Source: Gazet van Antwerpen.

The trial of Flemish SS in Mechelen Source: Gazet van Antwerpen.Breendonk II

The history of Breendonk was not over when the camp was liberated. In the tumultuous period after the liberation, a black page was added to the history of the fort.

One day after the last German had left the fort, it was put into use again. Police and state police, but also the local resistance, locked up the first "incivieken" or collaborators. The vacuum of power was the main problem in this period. The government did not return until September 8th and the Allied troops were too busy dealing with the retreating Germans. This meant that there was no legal authority to maintain order. Police and state police were under staffed and insufficiently armed. The resistance, which was well organized and armed, had carte blanche. They took control of Breendonk. The commander was Baron Leopold De Meester of the Secret Army. His direct subordinate was Maurice Mariotte, also a member of the Secret Army and commander of the sector Klein-Brabant. Other commanders of the fort were Frans Brabants and De Meester from the Belgian National Movement (BNB).

In the repression, during the early days of September, thousands of "blacks" and (alleged) collaborators were arrested. Because the prisons did not provide sufficient space, empty barracks and camps like Breendonk were used as well. Resistance members, many of whom only had joined the resistance in the last month of the war, attacked collaborators and anyone they suspected. Their homes were smashed to pieces and even set on fire. Women were close-shaved and tarnished with swastikas. Others were badly beaten and tortured. Often it was merely a matter of pleasure. Many people became victims of personal revenge. The list of innocent victims is long.

Life was tough in Breendonk II. Just like in the SS period, the prisoners were abused, beaten and famished. Rape and apparent executions were the order of the day. Prisoners were even compelled to box against each other. One of the most notorious female guards was the sadistic "Aunt Jeanne" (Jeanne Hoekmans). She was arrested in November 1944 and sentenced to an imprisonment of three and half years. Lévy, one of the Breendonk prisoners during the war, testified after one of his visits to the fort during the repression: "Collaborators are locked up and treated like we were treated by the Nazis. This inhumanity makes me sad".

The Belgian government was aware of this state of affairs, but were initially unable to take action: the resistance groups ignored the governmental orders. It was only until the British army command learned about what was going on and condemned the "shocking excesses", that the affair gained momentum. On October 11th, 1944, the incarcerated collaborators were transported to the Dossin barracks with trucks.

In late December 1944, Breendonk was taken back into use as an internment centre because of a lack of space. Nearly 800 people were incarcerated and in the custody of state police officers and soldiers. Breendonk remained an internment centre until 1947. On August 19th, 1947, Auffanglager Breendonk was officially declared a National Memorial of Fort Breendonk. In 1948 the fort was formally transferred to the Board of Directors of the foundation.

Definitielijst

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Images

Information

- Article by:

- Gerd Van der Auwera

- Translated by:

- Chrit Houben

- Published on:

- 20-09-2012

- Last edit on:

- 02-05-2020

- Feedback?

- Send it!