Introduction

Operation Barbarossa may well be one of the most intriguing events in military history In any case, the German invasion of the Soviet Union was the largest military operation until then. On June 22, 1941, over 3 million German soldiers in three army groups advanced eastwards in order to eradicate the Red Army once and for all.

Definitielijst

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

Prior to the invasion

Hitler’s personal crusade

During the twenties, Adolf Hitler had already indicated in his political testament Mein Kampf that Germany’s ultimate goal lay in the East. There, in his words, would be sufficient space, Lebensraum to meet the needs of the entire German population. In addition, Hitler considered Bolshevism his arch enemy. He claimed Communism was a part of an international Jewish conspiracy. It was Hitler’s intention that the war against the Soviet Union was to be the largest war of extermination in human history. This goal was intensified by the notorious Kommisarbefehl in which captured Soviet Kommissars were to be executed immediately. Moreover, Hitler used the argument that the Soviet Union had neither signed the Geneva Convention, nor the Hague Convention, giving the German soldiers a free hand in committing war crimes on a large scale without having to answer to military courts.

The murderous goals of Barbarossa had been indicated clearly, in contrast to the military objectives. As it was, the Wehrmacht lacked a strategic ultimate goal. The marching orders for Operation Barbarossa only mentioned the necessity to destroy the Soviet armed forces. The geographic ultimate goal became unclear immediately. This caused insecurities about the strategy to be followed between Hitler on the one hand and the general staff of the OKW (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht) and the OKH (Oberkommando des Heeres) on the other hand. The commanders in the field, who actually had the best insight into the strategic situation, had trouble understanding the tasks allocated to them and during the campaign they were at odds with both Hitler and the general staff. In this way Adolf Hitler created insecurities and rivalries between the units concerned and the commanders, perhaps on purpose. Operation Barbarossa clearly was his own personal crusade. This would gradually become clearer as the war against the Soviet Union unfolded.

Joseph V. Stalin had done all he could to prevent the inevitable confrontation between the two totalitarian states. The Molotov-Von Ribbentrop Pact of August 1939 had made Stalin think he could keep the Soviet Union out of the war. In additional secret protocols, Eastern- Europe was divided between Germany and the Soviet Union. In September 1939, Germany had run the gauntlet during the campaign against Poland after which the Red Army advanced into Eastern Pomerania and had demanded its share. While Hitler was sure the Soviet Union wouldn't intervene in a war against France and Great-Britain, Stalin focused on the Baltic States and Finland which had been allocated to the Soviet Union in the secret protocols. Soviet garrisons and naval bases were established in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania but Finland was unwilling to give in to the Soviet demands and give up territory. Consequently, a military conflict erupted in December 1939 which would be known as the Winter War.

Shame on the Red Army

The Red Army invaded tiny Finland with a majority in men and material. The Finnish troops, extremely well trained, managed to outclass the Soviets however by using guerilla tactics where brigades on skis in the snow covered woods cut the Soviet mechanized columns to pieces (the motti tactics) and destroyed them. Losses on Soviet side were disastrous and in January 1940, changes were made within the Soviet high command. After the arrival of additional reinforcements, the Mannerheim line was finally breached and consequently, on March 13, 1940, a peace treaty was agreed upon. During the Winter War, the Soviet Union may well have achieved her military goals but at the cost of horrendous losses. The Red Army had shown such a lack of efficiency that her reputation, gained during the thirties, was lost for the most part.

Hitler now turned his attention westwards though where in April 1940, the Wehrmacht executed a brilliant operation, Operation Weserübung By the combined deployment of land, sea and air forces, Norway and the French and British forces fighting there, were forced to surrender.

May 1940

Even before hostilities in Scandinavia had ceased, the Wehrmacht struck at Western-Europe as well. On May 10, 1940, German forces invaded the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxemburg, crossing into France within a few days. With this operation, code named Fall Gelb, the German forces lured the Allied armies to the north in order to subsequently separate them from the rest of France by a strong attack through the Ardennes and further along the French-Belgian border.

Not all isolated troops managed to escape during the spectacular evacuation from Dunkirk but they were no longer operational. They had had to leave all their heavy weaponry and other equipment behind on the beaches and there were no replacements. What followed was the battle of France which ended like it had begun: with a French government incapable of taking the initiative and resigning to German control: Vichy France.

Hitler in Paris at the pinnacle of his power. With Great Britain isolated in the west, the road was clear for conquests in the East Source: National Archives and Rcord Administration

Stalin was stunned by the quick German victories in the west because he had seriously reckoned with a war of attrition. Stalin took precautionary measures and decided to strip the Baltic states of their independency and officially annex Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania in summer. He aroused Hitler’s anger by occupying the German part of Lithuania as well. Subsequently the Soviet Union rushed to gobble up Bessarabia and North-Bukovina as well which wasn’t part of the deal. This way, the Rumanian oil fields came well within range of the Red Army.

Meanwhile Hitler had risen to the pinnacle of his power after the fall of France. He was convinced that the British were as good as defeated and he wanted to attack the Soviet Union immediately. The German generals were stunned and managed to convince Hitler that an attack on Russia in the fall of 1940 would be an impossible undertaking.

The battle of Britain

The Wehrmacht meanwhile had set its sights on Great-Britain. The British had managed to retrieve most of their armed forces during the evacuation from Dunkirk and were preparing for a German invasion. Prior to the campaign against France and the Low Countries, the Germans hadn't drafted any plans yet for an invasion of the British Isles. The Germans had hastily started planning the invasion of Great-Britain, code named Operation Seelöwe. Hitler hardly paid any attention to the campaign against England. During talks on July 21, 1940, with the commander-in-chief of the army, Generalfeldmarschall Walther von Brauchitsch and the chief of staff of the OKH GeneraloberstFranz Halder, Hitler revealed his dark intentions in deepest secrecy: ‘We have to get rid of Russia.

Nonetheless, the battle of Britain kicked off in mid-August 1940 with large scale actions by the Luftwaffe over the Channel and southeastern England. The Germans hoped to destroy the RAF by air strikes and force the country to sue for peace, making a bloody invasion superfluous. British fighter pilots however managed to defeat the Luftwaffe in the nick of time during heroic dogfights over southeastern England, causing the German high command to postpone Operation Seelöweindefinitely

During the battle of Britain, the Germans suffered their first strategic defeat. From then on, Hitler focused all his attention on planning an invasion of the Soviet Union. By defeating the Red Army, he thought to eliminate Great-Britain’s only possible ally on the European continent so ultimately, Britain would be compelled to surrender.

Hitler now intended to do exactly what he had always wanted to prevent in his political and military strategy: wage a war on two fronts. Indeed, the British were incapable to launch an amphibious attack on the European continent on short notice but they had already proved they were not ready to give up the fight.

Overconfident from the previous successes, German staff officers started planning a campaign against the Soviet Union. Some German generals, among them Großadmiral Erich Raeder and Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm Keitel were very skeptical about an attack on the Soviet Union initially. The defeat of the French war lord Napoleon Bonaparte, who was defeated in 1812 in the cold and vast Soviet Union was still on their minds. But if it had to be done, it should become a quick and decisive victory.

Definitielijst

- Communism

- Political ideology originating from the work of Karl Marx “Das Kapital” written in 1848 as a reaction to the so-called class struggle between the proletariat (labourers) and the bourgeoisie. According to Marx the proletariat would take over power from the well-to-do classes though a revolution. The communist movement aspires an ideal situation where the means of production and the means of consumption are common property of all citizens. This should end poverty and inequality (communis = common).

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Lebensraum

- “Living space”. Nazi term indicating the need for the overpopulated German lands to expand.

- Luftwaffe

- German air force.

- Mein Kampf

- “My Struggle”. Book written by Adolf Hitler, outlining the principles of National Socialism.

- mid

- Military intelligence service.

- OKH

- “Oberkommando des Heeres”. German supreme command of the army.

- OKW

- “Oberkommando der Wehrmacht”. German supreme command of the Armed Forces, Army, Air Force and Navy.

- RAF

- Royal Air Force. British air force

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- strategy

- Art of warfare, the way in which war should be conducted in general.

- war crimes

- Crimes committed in wartime. Often concerning crimes committed by soldiers against civilians.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

The German plan of attack

On July 31, 1940, Adolf Hitler gave the order to finalize the first plans for the invasion of the Soviet Union. Generaloberst Franz Halder ordered the talented chief of staff of 18. Armee Generalmajor Erich Marcks to start an investigation into the problems which would be encountered during an attack in the east.

The Plan Marcks

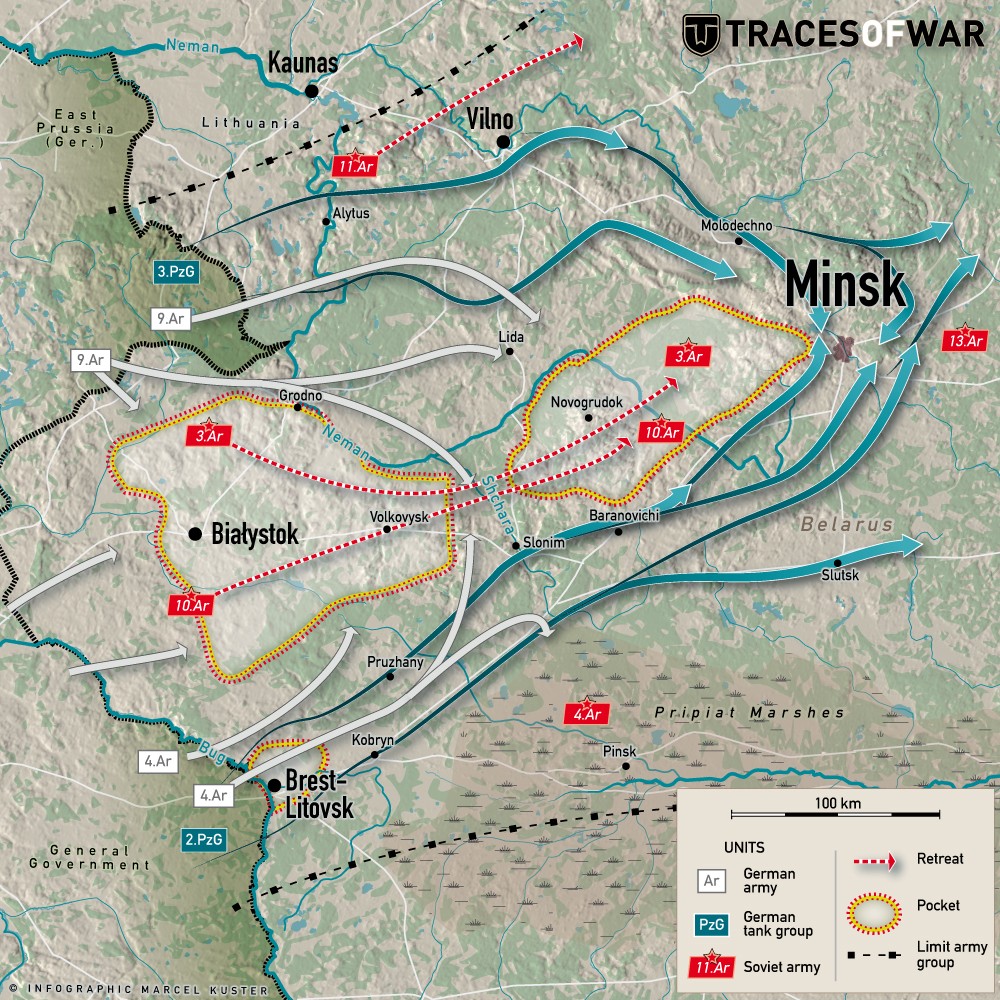

On August 5, Erich Marcks submitted his first report to Halder, the first version of the operational plan for the east. According to this Plan Marcks, two army groups were to attack the objectives Moscow and Kiev. The largest army group (with the major part of the armored forces) was to advance on Moscow and at the same time deploy troops to capture the Baltic states and Leningrad. This secondary task should not be detrimental to the main strike towards Moscow. The southern army group was to strike in the direction of Kiev, supported by an army operating from Rumania. After Moscow had been taken, the northern army group would turn south to support the units that were to capture the Ukraine.

The Plan Marcks foresaw a German force of 110 infantry divisions, 24 armored divisions and 12 motorized divisions facing 96 Russian fusiliers divisions, 23 cavalry divisions and 28 mechanized brigades. Marcks had kept 40 divisions in reserve to exploit any breakthrough. Actually, the Red Army had to be destroyed between the rivers Dvina and Dniepr and the entire operation should not take more than 17 weeks. In short, the Red Army had to be destroyed in 4 months and Russian resistance nests be cleared.

The most important characteristic of the plan was the designation of Moscow as the main target. The staff of the OKH was convinced that the Soviets would assemble their main body before Moscow and that the final blow be delivered there. The OKH was of the opinion that after the capture of the capital of the Soviet imperium, chances were high that the Red Army and the Soviet population would end armed resistance.

Aufbau Ost

Not only the OKH was involved in the initial stages of planning a campaign against the Soviet Union. On August 9, the OKW issued the order Aufbau Ost. This entailed the build-up of forces on the eastern border for an attack on the Soviet Union. Roads, railways and air fields were constructed, the communication networks were expanded and stockpiles of supplies and ammunition were established. Moreover, the OKW ordered the German military intelligence service, Fremde Heer Ost with Oberst Eberhard Kinzel in charge, to intensify the activities against the Soviet Union and gather intelligence as to the Soviet armed forces and their locations.

Early September, GeneralleutnantErich Paulus had started planning the coordination of the campaign against the Soviet Union. The German movements of troops eastwards got under way after in early September a deal was closed with Rumania to dispatch a German military mission which was to instruct the Rumanian army. In addition, specialists in the field of air defense were sent to the Ploesti oil fields, followed by German troops in October. In order to appease the Soviet Union, the Nazi government declared that large scale military exercises were being held in the east.

While in the west the fighting during the battle of Britain reached a climax and Hitler began postponing Operation Seelöwe, the OKW finalized its own investigation into the problems of a campaign against the Soviet Union. This plan, drafted by OberstleutnantBernhard Lossberg, called for three army groups. The northern group was to advance on Leningrad, the group in the center via Smolensk to Moscow and finally the southern group was to advance on Kiev. Therefore the army groups were named Heeresgruppe Nord, Mitte and Süd respectively. The main difference between the Marcks plan and Lossberg’s was that the latter wanted to have the army groups advance at the same speed and therefore demanded that Heeresgruppe Mitte would halt near Smolensk in order to allow Heeresgruppe Nord to catch up.

Gathering information

Soviet security made efficient and extended espionage extremely difficult. Therefore, reconnaissance flights over Soviet territory began in October. German aircraft equipped with cameras covered an ever increasing area of European Russia, recording Soviet troop concentrations, gathering details about frontier defenses and pinpointing Soviet airfields. Consequently, German estimates of Soviet troop strength in the center of the potential front had to be adapted accordingly.

At the end of October, German plans for an invasion of the Soviet Union were thwarted by the Italian invasion of Greece. At that time, Adolf Hitler and Stalin had just agreed on an exchange of thoughts to which Vyacheslav M. Molotov, the Soviet People’s Commissioner of Foreign Affairs, would be expected in Berlin on November 12 because Soviet-German relations began to cool down gradually.

That very day, even before the negotiations with Molotov began, Hitler issued a directive indicating that notwithstanding the outcome of the diplomatic talks, preparations for the attack were to continue. The talks with the People’s Commissioner proceeded very roughly and Molotov even had to seek shelter because of a British bombardment on Berlin. Molotov turned out to be a tough negotiator but Hitler and Reichsaußenminister Joachim van Ribbentrop didn't accept the Russian’s demands. Molotov therefore returned to Moscow empty-handed.

At the end of November and the beginning of December strategic map exercises were conducted by the officers who would probably be in charge of the three army groups, supervised by GeneralleutnantFriedrich Paulus. The conclusion was drawn that it would be of great importance to break Soviet resistance on or in front of a line stretching from Kiev to Minsk and further towards Lake Peipus, a conclusion which had already been drawn from earlier research.

Halder’s plan: Operation Otto

On December 5, 1940, Generaloberst Franz Halder revealed the final plans of the OKH. Halder made three offensives of what in the Plan Marcks initially had been two. The entire area of operation was divided in two halves, a northern and a southern separated by the Pripjat marshes considered impassable. Leningrad became the main target of the offensive in the north and the thrust towards Moscow was reinforced at the cost of the offensive against Kiev. The final objective of the operation should be the river Volga and the area around Archangelsk and 105 infantry and 32 armored and motorized divisions would be deployed. This order of battle became known by the name of Otto. Hitler agreed with the sketch and subsequently added a few personal remarks. Although he agreed with the plan in general, he suggested detaching the mobile forces of Heeresgruppe Mitte after a while and direct them northwards.

At this meeting, Hitler hadn't only conducted lengthy negotiations about the proposed military operation against the Soviet Union but also about the strategic consequences of his plans and decisions. As the Italian campaign against Greece was proceeding far from favorably, Hitler meanwhile had decided to launch his own attack on Greece in the spring of 1941. After having defeated the Greeks, the armed forces deployed in the Balkans were to be made available to the campaign against the Soviet Union. Hitler expected Yugoslavia to join the Axis. Finland and Rumania would also be persuaded to join in the attack against the Soviet Union.

The intended policy of occupation

Hitler held the military capacities of the Red Army in low esteem. He claimed: ‘Kick in the door and the whole rotten structure will collapse.’ The timing for an attack on the Soviet Union was, according to Hitler, never as favorable as now. He intended to crush the Red Army in a defeat that was even more humiliating than the defeat of the French armies in 1940. Once the German troops had reached the river Volga the campaign would be over and from this line, raids would held against enemy weapons centers deep in the Russian hinterland. Subsequently, Germany would create buffer states: the Ukraine, Belorussia, Lithuania and Latvia. The General gouvernement Poland would be expanded as well and Finland and Rumania would be rewarded with territorial expansion for their participation in the campaign against the Soviet Union.

It was an enormous vast, aggressive and cruel plan although the military commanders, party big wigs and the SS death squads would have to wait a while before they would learn how monstrously inhumane it would become. Hitler was still pondering the ideological aspect of his ‘anti-Bolshevik and anti-Slavic crusade’, a mixture of Nazi racial concoctions and outright colonialism. The contempt Untermensch (subhuman), the Slavic inferior who escaped actual extermination could expect no other fate than slavery and exploitation.

The power struggle between the various organizations and institutions which were to apply this ‘policy in the East’ had also begun. One by one, the various government departments began interfering in the plans for the exploitation of the captured territories. The departments of Agriculture and Economics, the armaments bureau of the OKW, Reichsminister Hermann Göring and his associates of the Four Year Plan and finally Alfred Rosenberg with his Ostbüro, established in the spring of 1941, all were competing who was to perform which task. Among them Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler who demanded his share as well in the spring.

Towards the end of the first week of December, the OKH had finalized the better part of the plans for the attack on the Soviet Union.General der Artillerie Alfred Jodl now ordered the OKW to include the plans in a preliminary directive. Those were completed on December 16 and were named Operation Fritz, Directive No. 21. The next day, Alfred Jodl handed the draft to Hitler.

Hitler’s new plan: Barbarossa

And then, Hitler came up with a major change in the draft of the directive. As he had indicated during the meeting of December 5, he wanted a part of the mobile forces of Heeresgruppe Mitte to swing north, after the extermination of Soviet forces in Belorussia had been completed, in order to cooperate with Heeresgruppe Nord advancing from Eastern-Prussia towards Leningrad and destroy the enemy formations in the Baltic states. Only after the cleansing of the Baltic area and the fall of Leningrad and the naval port of Kronstadt, the advance on Moscow was to be put in motion.

With this interference Hitler had shoved the major focus of the military planning aside as the direct advance on Moscow had been part of the German plans for attack from the beginning. Urged on by Hitler, this completely different maneuver was included in the directive. Neither the OKW nor the OKH made any attempt to undo the alterations.

On December 18, 1940, Hitler signed Directive Nr. 21 for the attack on the Soviet Union with the sinister codename Barbarossa. Hitler drew his inspiration from Friedrich Barbarossa who had been in charge of the Third Crusade against the Muslim armies of Saladin in 1189. In Hitler’s eyes, Operation Barbarossa was a crusade as well, this time however against the ‘Bolshevist non-believers’, a plan which would soon be executed with similar medieval cruelty.

The directive Barbarossa was long and complicated. The German forces were to ‘crush Soviet Russia’ in a lightning campaign for which the preparations had to be completed on May 15, 1941. The main body of the Red Army was to be annihilated in the western part of Russia and its retreat into the ‘vastness of the Russian territory’ had to be prevented. The final goal of the Germans was the establishment of ‘a line of defense against Asiatic Russia’, stretching from the Volga to Archangelsk. ‘The last industrial area still in possession of Russia in the Ural can subsequently be eliminated by the Luftwaffe’.

Rumania and Finland, spring boards for the attacks on the southern and northern flank, would be ‘possible allies’ and in the north, the Swedish railways would probably be available to facilitate the delivery of supplies to the German forces in Finland.

Adolf Hitler during the plannnig of Operation Barbarossa. To his left, Generalleutnat Friedrich Paulus, who was given command of 6. Armee in 1942 which was annihilated in Stalingrad Source: Public domain

Setting up marching orders

As the frame work of Operation Barbarossa was now known, drafting of the marching orders could begin. Heeresgruppe Mitte would be commanded by Generalfeldmarschall Fedor von Bock and was allocated the better part of the armored forces. In the frontline north of the Pripjat marshes, this army group was tasked with the destruction of the Soviet forces in Belorussia. A possibility should be left open to have strong mobile units swing north in order to support Heeresgruppe Nord in its operations. This unit, commanded by Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb was, on paper, the poorest equipped of the three army groups. It was tasked with trampling the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania annexed by the Soviet Union, capturing the Soviet naval bases in the area and subsequently push through to Kronstadt and Leningrad.

South of the Pripjat marshes Heeresgruppe Süd, commanded by Generalfeldmarschall Gerd von Rundstedt, was to penetrate the vast Ukraine. This unit was to advance from southern Poland as well as from Rumania. Von Rundstedt was to destroy the Soviet formations in the west of the Ukraine and Galicia and subsequently establish bridgeheads on the eastern banks of the Dniepr and finally advance on Kiev or Rostov.

The role of the allies

In the meantime, Rumania had practically become a German military satellite. While Hitler himself was winning over the Rumanian dictator Marshall Ion Antonescu, a Luftwaffe contingent saw to the defense of the oilfields at Ploesti. A military mission coordinated the reform of the Rumanian army and was setting up plans for a German-led attack by the Rumanians on the Soviet Union.

The Finns held a special place. In the late summer of 1940, they were questioned about a German-Finnish cooperation. Soon after, they joined Germany, not in a real alliance but in a Waffenbruderschaft (brothers in arms). German troops advanced into Finland and the main body of the Finnish army was ordered to cooperate with Heeresgruppe Nord in the attack against Leningrad.

It is extremely odd that the Italians were not involved in the planning of Operation Barbarossa at all. Just one day before the launch of the operation, Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini was informed about the German plans to attack the Soviet Union in a letter written by Hitler himself. The Japanese didn't know about Hitler’s plans either. The Three-Power-Pact was considered a military pact only when it suited Hitler. In April, even a neutrality agreement was signed between the Soviet Union and Japan. An agreement that would have far reaching consequences for Soviet strategy.

On March 17, 1941, Hitler decided Hungary wouldn't be involved in Operation Barbarossa and Slovakia would only be used as a supply base and assembly area. In February German troops had already been given permission for a free passage through Bulgaria; its location being of more importance for the attack on Greece however than for the campaign against the Soviet Union.

More changes in the plan of attack

After December 1940 the German plan of attack was altered in only two ways. German troops were stationed in the extreme north of occupied Norway (AOK Norwegen) in order to launch an attack on Petsamo and subsequently advance on Murmansk in cooperation with the Finns. In this way, Hitler hoped to be one step ahead of possible British amphibious landings and eventually quell them in the bud. This military action was named Silberfuchs

The other change of the plan involved the southern sector. Hitler felt uneasy about a possible British intervention in Greece, causing him to order the relocation of troops of Heeresgruppe Süd to Bulgaria. This robbed Generalfeldmarschall Gerd von Rundstedt of a considerable part of his forces and so he had to abstain from the intended double pincer movement in the Ukraine. On March 17, 1941, Hitler decided that the army group should concentrate its major attack on the left flank of the area of operation. Hitler expected a straight advance towards Kiev out of southern Poland from Heeresgruppe Süd. In the initial stages, 11 Armee on the right flank was to secure the safety of the Rumanian oilfields. After the capture of Kiev, the left flank, (6 Armee and Panzergruppe 1) was to push through to the Black Sea. These changes in the plans were to have decisive consequences for the progress of Operation Barbarossa.

Events on the Balkans

On March 25, 1941, the Yugoslav pro-German government had signed the Three-Power-Pact and in so doing had joined the Axis powers. One day later however, a coup was staged by Serbian officers. Hitler was furious and on March 27, in Führer directive Nr. 26, he ordered the capture of Yugoslavia. The Serbian people had a long standing and good relationship with Russia and consequently on April 5, a non-aggression pact was signed between the new Yugoslav government and the Soviet Union. One day later, Belgrade was bombed by the Luftwaffe in Operation Bestrafung and German troops invaded both Yugoslavia and Greece.

The Wehrmacht having to take unexpected action in Yugoslavia caused Hitler to postpone Operation Barbarossa. After the end of operations in the southeast, it would take four to six weeks before the campaign against the Soviet Union could begin. It is an open question however whether the attack against Russia could have been launched earlier because of the extremely heavy rainfall in the spring of 1941, making the Russian roads impassable and crossing the rivers would have caused serious problems as they had swollen to well beyond their banks.

After the capture of the Balkans, the German formations which were to take part in the conquest of the Soviet Union returned to their original jump-off points on the Russian border. On June 5, Hitler approved the new time table. Operation Barbarossa was to be launched on June 22, 1941 at 03:15 hours.

Definitielijst

- Armee

- German unit. Mostly consisted of three to six army corps and other subordinate or independent units. An Armee was subject to a Heeresgruppe or Armeegruppe and had in theory 60,000-100,000 men.

- cavalry

- Originally the designation for mounted troops. During World War 2 the term was used for armoured units. Main tasks are reconnaissance, attack and support of infantry.

- Four Year Plan

- A German economic plan focussing at all sectors of the economy whereby established production goals had to be achieved in four years time.

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- Heer

- German army or land forces. Part of Wehrmacht together with “Kriegsmarine” and “Luftwaffe”.

- Heeresgruppe

- The largest German ground formation and was directly subordinate to the OKH. Mainly consisting of a number of “Armeen” with few directly subordinate other units. A Heeresgruppe operated in a large area and could number several 100,000 men.

- infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Luftwaffe

- German air force.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- neutrality

- Impartiality, absence of decided views, the state of not supporting or helping either side in a conflict.

- non-aggression pact

- Agreement wherein parties pledge not to attack each other.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- OKH

- “Oberkommando des Heeres”. German supreme command of the army.

- OKW

- “Oberkommando der Wehrmacht”. German supreme command of the Armed Forces, Army, Air Force and Navy.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- strategy

- Art of warfare, the way in which war should be conducted in general.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

The Wehrmacht in 1941

During the campaigns in Poland in 1939 and France and the Low Countries in 1940, the Germans had proved to possess one of the best war machines in the world. The Wehrmacht had inflicted a massive defeat on the Western Allies in lightning campaigns. Poland was defeated in a month and France fell within six weeks. Therefore the morale of the German soldier was higher than ever. In the spring of 1941, the German forces, in the campaigns against Yugoslavia and Greece, had proved once again they could defeat almost any opponent.

The decisive factors in the German victories had been supremacy in the air over the battlefield and the flexibility of the armored forces. In the campaign against the Soviet Union, the entire German strategy hinged on the speed of the tanks once again.

The armored forces

For an efficient execution of Operation Barbarossa however, the Germans needed more tanks than were available in the summer of 1940. On September 10, Hitler personally ordered a reorganization of the armored divisions and the number was doubled. This however at the cost of the numerical strength. The Panzerdivision of 1941 consisted of just one regiment of two battalions, although six divisions consisted of three. The tank battalions consisted of two companies of light and one company of medium tanks, while the infantry brigade in each tank division consisted of two motorized regiments, a battalion motorbikes, three medium artillery battalions and a battalion anti-aircraft guns equipped with the excellent 88mm weapon. Hence each tank division was made up of between 150 and 200 tanks which was half the numerical strength of the original tank division. All told, there were 46 tank battalions for the 20 tank divisions of the German army. For Operation Barbarossa no less than 19 of the 20 tank divisions were being deployed.

On June 22, the Germans had some 3,750 tanks at their disposal. The majority consisted of the PzKpfw III and PzKpfw IV (Panzerkampfwagen). During the campaigns in France and the Low Countries, these tanks had proved they met the demands of modern warfare. There was however a high number of obsolete light tanks in use, such as the PzKpfw I, PzKpfw II and the original Czech PzKpfw (35)t and the PzKpfw (38)t. These old models had turned out to be extremely vulnerable to enemy anti-tank fire during previous German campaigns and were in urgent need of replacement. Due to shortage of tanks however, the Germans were compelled to deploy these light tanks once more. More disturbing for the Germans was the fact that the production numbers of the PzKpfw III and PzKpfw IV were far below the number required. In the course of the campaign, this would cause problems for the Wehrmacht as Soviet production numbers were considerably higher. The German high command was very aware of this, notwithstanding Hitler’s disregard of reports about a massive Soviet strength in tanks. Moreover, it was assumed the Red Army possessed a new type of tank, even heavier than the PzKpfw IV. Despite these problems, the German army put its faith in the technical superiority of its equipment and the capabilities of its tank commanders.

The infantry

In contrast to what is often assumed, during World War Two the German army was for from an entirely motorized force. As the country had an acute shortage of motorized vehicles, only a limited number of formations was fully motorized. The better part of these formations was allocated to the armored forces, although for Operation Barbarossa the Germans had 15 motorized infantry divisions at their disposal. These divisions, thanks to their speed and flexibility, were able to gain successes at the forefront and in occupied areas and to consolidate junctions in the rear of the enemy. A serious disadvantage however was that these divisions were for a part equipped with French trucks, captured in 1940 which were not so well suited to the harsh conditions in the Soviet Union as their counterparts produced in Germany.

Part of the motorized divisions belonged to the Waffen-SS. These divisions, the SS-Leibstandarte, SS-Das Reich, SS-Totenkopf and SS-Wiking were part of the order of battle of the Wehrmacht in 1941. In previous campaigns, the Waffen-SS had proved itself equal to the regular troops. Although the average losses of these SS units were considerably higher than in other units, the Waffen-SS had displayed exceptional courage and endurance and in Yugoslavia and Greece, they had even claimed the leading role.

The majority of the infantry formations wasn't motorized however and they had to cover the immeasurable distances in the Soviet Union on foot. Moving supplies and artillery pieces was largely done by horses. Prior to the launch of Operation Barbarossa, the German army had 600,000 horses at its disposal. After Hitler had decided to attack the Soviet Union, the number of infantry divisions was increased. All told, for the campaign against Russia, Germany had 119 infantry divisions at her disposal. Earlier campaigns had already indicated that the enemy could often escape from an encirclement created by the tanks if the infantry couldn't reach them in time to shut the trap. As highly successful as the armored forces could be, success of the German advance still depended on the speed with which the infantry could advance.

The fighting in France had shown that that German infantry had serious trouble in the defense against enemy tanks. The 3,7cm anti-tank piece appeared not to be powerful enough to disable a reasonably armored tank. After the campaign in France it was decided to replace the 3,7cm gun with a more powerful 5cm one. In June 1941 however, the majority of the German infantry divisions was still equipped with the 3,7cm gun.

The glorious Wehrmacht marching through Paris in the summer of 1940 Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1994-036-09A/CC-BY-SA

The Brandenburger units were tasked with special operations in the rear of the Soviets. These highly trained commandoes were to create confusion and chaos in Soviet communications or secure special tactical objects like bridges and road junctions. These commandoes infiltrated in the Soviet lines in the night prior to the invasion or were parachuted behind enemy lines. Moreover, in the months prior to Operation Barbarossa, the German secret service recruited Ukrainian nationalists who were also tasked with actions of sabotage, the Nachtigal Regiments). In the Baltic states, where the Soviet regime had only recently been established, the German secret service also made contact with resistance groups who were willing to cooperate with the German plans to disrupt the Soviet rear.

The Luftwaffe

In the previous campaigns the German Luftwaffe had played a major part in the battles. In Operation Barbarossa 2,770 aircraft (65% of the total number at the disposal of the Luftwaffe) were allocated to gain air supremacy and destroy the Red Air Force. Moreover, the Luftwaffe played an indispensable role in support of the German ground forces.

The Luftwaffe’s standard fighter was the Messerschmitt Bf 109. This was a formidable fighter. Although the Germans had a superb fighter at its disposal, other German aircraft were outdated. The notorious Junkers Ju 87 depended on air supremacy in order to survive while the Heinkel He 111, Dornier Do 17 and the Junkers 88, Germany’s most important bombers, were all short on payload and range.

During the Battle of Britain, the Luftwaffe had suffered painful losses and the German aircraft industry hadn't compensated those yet. In June 1941, the Luftwaffe was short of 200 aircraft as compared to the previous year. Consequently, these shortcomings and the need to operate from improvised air fields made it extremely difficult for the pilots to achieve supremacy, also because the air space over the Soviet Union was so vast. In the thirties, the Luftwaffe had been established as a tactical air force which was more than able to provide short range ground support but due to the total lack of long range bombers it was unable to stage an effective campaign against far off enemy targets.

The Kriegsmarine played a supporting role in Operation Barbarossa. It was tasked with mine laying in Russian territorial waters, establish blockades and played a major part in support of the artillery of Heeresgruppe Nord in attacks against Soviet ground forces in the Baltic.

Rumanian troops

Germany’s most important ally was Rumania, headed by dictator Marshall Ion Antonescu who was also Commander-in-Chief of the Rumanian armed forces. From October 1941 onwards, a German delegation had assisted in restructuring the Rumanian army. Despite efforts to increase the striking power of the Rumanians, they army lagged far behind the German troops where fighting quality was concerned. The Rumanian army participated in Operation Barbarossa by deploying 358,140 men, divided into two armies. Those two, the Third and Forth Army together with the German 11. Armee made up Heeresgruppe Antonescu.

In accordance with the agreement with Finland, German troops were stationed in the north who, in collaboration with the Finnish army commanded by Field Marshall Carl Mannerheim, would launch operations to regain the territory lost in the Winter War of 1939-1940. In the extreme north of Norway and Finland, troops had been stationed to launch an attack on Murmansk. This would also be a combined German-Finnish operation. All told, the Finns deployed 302,600 men to undertake offensive operations against the Red Army.

Vernichtungskrieg

Adolf Hitler had already indicated in a speech to his generals on March 30. 1941, that Operation Barbarossa was to become a war of annihilation. The responsibility of the army was limited to the area of operation. Hence the military had to determine the limits of their consciousness ….. or ignore them. In the notorious Kommissarbefehl of June 6, 1941, this policy was emphasized once more. Communist Kommissars and authorities, whether civil or military, were outlawed entirely. They were to be sentenced to death on the spot without any sort of trial. Early March 1941, Hitler had already ruled that courts marshal would only handle military cases. As soon as they were captured, Kommissars were to be executed immediately. If German fighting forces hadn't already done so, the murder squads would see to it.

These squads, better known as Einsatzgruppen had been established in 1941 by Reinhard Heydrich, Heinrich Himmler’s right-hand man. To each army group, one murder brigade was allocated. Although they operated independently from the army and were only answerable to Heinrich Himmler, they actually collaborated closely with the command of the army, which was responsible for instance for their transport and care. The main task of these Einsatzgruppen was to exterminate the Jewish population in the captured areas of the Soviet Union.

Logistical problems

Germany’s main weakness was logistics. In the vastness of the Soviet Union there were hardly any paved roads and the Russian track gauge differed from that in Germany. Hence, the Wehrmacht depended on captured Russian rail equipment for its supplies. Moreover, the diversity of German weaponry required a large maintenance and repair system. In the planning of Operation Barbarossa, this had hardly been taken into account.

Perhaps Germany’s most serious mistake was that she hadn't adapted its economy at all to the circumstances of war. Shortages of raw materials and fuel formed a serious disadvantage for German industry. In June 1941, German industrial economy had come to depend on 3 million foreign forced laborers and due to mandatory conscription, these shortages only increased. Just like in previous operations, Hitler reckoned on a lightning victory and so, an eventual prolongation of the war during the winter wasn't taken into account at all. It would be and had to be a swift victory, otherwise the Third Reich would soon be facing serious problems.

Definitielijst

- brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- collaboration

- Cooperation of the people with the occupying forces, more generally spoken the term for individuals who cooperate with the occupying force is collaborator.

- Heeresgruppe

- The largest German ground formation and was directly subordinate to the OKH. Mainly consisting of a number of “Armeen” with few directly subordinate other units. A Heeresgruppe operated in a large area and could number several 100,000 men.

- infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Kriegsmarine

- Germa navy. Part of the Wehrmacht next to Heer and Luftwaffe.

- Leibstandarte

- Elite troops, originally Hitler’s body guards. Starting as a motorized infantry regiment it grew into a Panzer division.

- Luftwaffe

- German air force.

- marshal

- Highest military rank, Army commander.

- mine

- An object filled with explosives, equipped with detonator which is activated by either remote control or by colliding with the targeted object. Mines are intended to destroy of damage vehicles, aircrafts or vessels, or to injure, kill or otherwise putting staff out of action. It is also possible to deny enemy access of a specific area by laying mines.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- strategy

- Art of warfare, the way in which war should be conducted in general.

- Totenkopf

- “Death’s head”. Symbol that was used by the SS. Also the name of an SS Division.

- Waffen-SS

- Name of Military section of the SS.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

The Red Army in 1941

Facing the best army in the world was a force that in 23 years had gained stormy and turbulent organizational, theoretical and operational experiences. During the first stages of the Russian revolution, and the subsequent civil war, the Bolshevist leadership needed armed forces to defend its seizure of power. Based on voluntary participation and other willing defenders of the regime, the Red Army of Workers and Farmers was formed (RKKA: Raboche Krestyanskaya Krasnaya Armia) in short, the Red Army

In order to have a sufficient number of men at his disposal, Lenin decided to introduce conscription. The Red Army grew into an army with 5 million men but owing to the prevalent war weariness and the strong prejudices against discipline and the orthodox military organization, desertion was wide spread, causing units to be disbanded and reestablished, depending on the mood of the local farmer-soldiers.

Irregular band of thugs

In general, the Red Army looked more like an irregular band of thugs that was kept together somehow by political commissars. A professional staff in Moscow, consisting of former Czarist officers, was in command of this army.

The Civil War was one of mobility in which the cavalry of both sides penetrated deep into territory occupied by the enemy in order to stage raids and cause confusion in the rear of the enemy. The poorly equipped infantry saw to the clearing of resistance nests. Eventually, the Red Army managed to gain the upper hand, causing the Communist regime to retain its seat in Moscow.

Following the Civil War, the Red Army was partially disbanded and reorganized. The major units were deployed along the borders and in densely populated areas while large cavalry formations were kept in reserve to stage offensive operations. It was the era of the semi-educated ‘red commander’, the ex-guerilla warrior who pulled the strings. The real military specialists, generally without a proletarian background, played an insignificant role. This situation was changed by the publications of M.V. Frunze, a successful army commander from the Civil War. He developed an entirely new way of military thinking which was to have a profound influence on the doctrine of the Red Army. The main characteristics of his thinking were to enforce world revolution by offensive operation and ideological education. Frunze also made an important contribution to the actual modernization of the Soviet armed forces. The authority of the political Kommissars in operational command was severely limited, thanks to Frunze.

Secret agreement with Germany

After the First World War, limitations were imposed on Germany by the Treaty of Versailles, drafted by the Western Allies. Development and production of certain types of weapons were prohibited. As Germany as well as the Soviet Union had reached an isolated position internationally, on April 16, 1922 in Rapallo, Italy, a political treaty was signed in which Germany recognized the Soviets as the official government of the Soviet Union. In secret though, economic and military agreements had been signed as well. German armaments factories were built in the Soviet Union and moreover, training facilities were set up by officers of the Reichswehr. In exchange, Soviet military were given the opportunity to take technical and tactical courses.

Although M.V. Frunze passed away in 1925, a new generation military intellectuals developed his ideas into useful strategies. Inspired by the lessons they had learned from German officers, solutions were sought to prevent trench warfare like during the First World War. The Soviets also used the lessons they had learned in the Civil War as to exploiting a breakthrough by cavalry formations. The final solution was found in the establishment of mechanized and motorized formations. In this context, people like Svechin and Triandafilov worked out a strategy which became known as the ‘in-depth attack’Gluboki Boy. In this theory, a victory should be achieved in a combined deployment of infantry, cavalry, tanks and aircraft. Tukhachevsky, one of the most influential red commanders saw to it that these revolutionary doctrines would be adopted by the Red Army and submitted requests to Stalin for the necessary weapons.

The Five Year Plans

Joseph V. Stalin introduced the Five Year Plans which were to provide the future units with these weapons. The Red Army however hardly had any experience in the production of tanks. A license was bought from Great Britain to produce the Vickers tank in the Soviet Union, which was developed further and later on produced as the T-26. The Soviet Union bought the Christie tank in the United States which would be developed further into the BT-2 and later into the BT-5 and BT-7

In 1930, the first tank brigade was established and in 1932, this number had increased to 4. Because of the increased production of tanks, in 1936, the Soviets were able to establish no less than 4 mechanized corps. Moreover in 1936, there was an abundance of mechanized brigades, tank regiments and tank battalions. In that year a mechanized corps was made up of over 560 tanks and 12,700 men. Cavalry corps and cavalry divisions were kept in reserve but these units were expanded with tank formations.

The Soviets were also the first to acknowledge the advantage of the deployment of air borne troops on a large scale. Experiments with those forces began during the thirties. It was decided to introduce the use of air landings in the rear of the enemy in Soviet military doctrine. After the army high command had been convinced of the benefit of air landings, establishment of air landing brigades was started that were even expanded to full size corps in the early fourties.

Halfway through the thirties, the Red Army yearly held large military maneuvers in the summer. Western observers were deeply impressed by what the Red Army displayed during these large-scale military exercises. In 1934, personal ranks were introduced and the authority of the political Kommissars was limited further. Moreover, a new general staff was appointed with the necessary training facilities. It may well be said that the unorganized band of thugs from the twenties had come of age which halfway through the thirties had grown into one of the most progressive armies in the world.

Experiments in Spain

In 1936, the Civil War broke out in Spain and Germany and Italy supported the Nationalists led by Franco in their struggle against the Republicans by delivering weapons and troops. Stalin thereupon decided to support the Republicans and dispatched aircraft, tanks and ‘advisors’ to Spain. During the fighting near Guadalajara a Soviet unit of tanks, commanded by Dimitri G. Pavlov, defeated two Italian motorized divisions. From this Pavlov drew the conclusion that the French way of using tanks in direct support of the infantry was the best way and that the Soviet theories about motorized units were flawed. On his return to the Soviet Union, he presented his ideas to the People’s Kommissar of Defense, Kliment E. Voroshilov who wasn't convinced anyway of the progressive ideas within the intellectual top of the Red Army. In accordance with the experiences in Spain, the mechanized formations were disbanded and the tanks distributed among the infantry formations and separately divided into small scale tank brigades which hardly had supporting units at their disposal.

Cleansing of the officers’ corps

At that time, the armed forces were struck by Stalin’s cleansing. Few events had more influence on the Red Army in 1941 than this systematic destruction of the high command that Stalin implemented between 1937 and 1939. Stalin’s motives for cleansing the army were first and foremost to secure his position as absolute ruler of the Soviet Union. As the army had weapons at its disposal and, moreover, there were leaders who owed their position, authority or prestige to Stalin, those leaders had to be eliminated just like it had happened in the Party. Three out of the five marshals, among them Tukhachevsky, 11 delegated Commissioners of Defense, 13 out of the 15 army commanders and all military leaders of districts in May 1937, as well as the most prominent members of the staffs of navy and air forces were executed in this period or vanished without a trace. The political apparatus, which was supposed to advice the career military, met the same fate. A total of 54,714 officers were ousted of which 15,000 were executed or disappeared forever. The rest was sentenced to long terms in prisons or labor camps. At the same time, some of the progressive ideas about the way to wage a war went down the drain. In fact, the Red Army was robbed of its brains.

Part of the military doctrine was retained but few officers were left over who could implement the revolutionary tactics. The officers ousted were replaced by politically dependable but inexperienced and mostly incapable commanders. This had grave consequences for the organization, coordination and the efficiency of the Soviet armed forces. Fear of the Stalinist regime prevented the remaining and newly appointed commanders from taking the initiative. In order to tighten his grip on the Red Army, Stalin had reinstated the authority of the Kommissars. Any order given by an officer had to be approved by them.

Experiences in the Far East, Poland and Finland

Since the early thirties, the Red Army had deployed a well-trained force on the eastern borders of the Soviet Union because of the threats by the Japanese. In 1938 and 1939, large scale border fights had raged between Siberian Soviet soldiers and the Kwantung Army. As Moscow had less influence on the command in the Far East, corps commander Gheorghy K. Zhukov, managed to defeat the Japanese with his troops in a combined deployment of tanks, infantry, artillery and fighter aircraft.

In the west, the Red Army swung into action as well in September 1939. Although Poland had been as good as defeated by the Germans, on September 17, the Red Army demanded its share of the Polish territory. This had been agreed upon in secret additional protocols in the Molotov-Von Ribbentrop Pact, signed on August 23 the same year. During the capture of eastern Poland serious problems became evident in the motorized units. Two tank corps participated in the advance to the west. These however were continuously held up by mechanical and logistic problems.

In December 1939, a conflict with Finland erupted, known as the Winter War. The achievements of the Red Army during the first month of the conflict didn't meet expectations and disastrous losses were suffered, without the pre-selected goals being achieved. The performance of the armored formations was poor. Many vehicles were lost to mechanical failure and logistics fell far short as well. Hence, armored formations were mainly deployed in support of the infantry.

Reforms

Regarding the German successes in Poland and Norway and the poor performance of the Red Army in Finland, a massive reorganization was put into motion in May 1940. First, changes in the overall command were made to the highest ranks of the military apparatus. The incompetent Marshal Kliment E. Voroshilov, People’s Commissioner of Defense, was replaced by Marshal Semyon K. Timoshenko and the chief of the general staff, Marshal Boris M. Shaposhnikov was replaced by Colonel-general Kiril A. Meretskov. Timoshenko sharpened discipline by imposing severe penalties for relatively minor violations. The rank of general, habitual in the Czar era, was reinstated and some of the ousted officers were rehabilitated, the best example being the release of the later Marshal Konstantin K. Rokossovsky. In June, some 1,000 officers were promoted. As a result, an officer generally held a position which was two ranks higher than what he had been trained for.

After the German victories in western Europe and the growing tension with the Nazis, it became clear in the Soviet Union that something had to be done in case a German invasion had to be repulsed. Hence it was decided towards the end of 1940 to reinstate the mechanized corps. Those corps however were larger than those in the thirties. In theory, in 1941 a mechanized corps consisted of had 1,031 tanks and 36,080 men. Yet these corps were hardly comparable as to organization and structure to the flexible yet complicated German armored formations.

Marshal Semyon K. Timoshenko worked out plans for an expansion of the Red Army which was to be completed in 1942. The outdated tanks were to be replaced by models which met the requirements of the modern battlefield. These new vehicles were to be allocated to no less than 29 mechanized corps. These were build up around the cadres of existing infantry formations and would be temporarily equipped with the newer models of the T-34 and the KV-1. In order to guarantee mobility of the motorized infantry formations, belonging to the mechanized corps, trucks and tractors were taken away from the artillery formations of the regular divisions. The major problem of the motorized units of the Red Army was the lack of communication. Men were poorly trained (military vehicles were secret so training had hardly been begun) and only a few vehicles were equipped with communication equipment. Sending messages was still done with signal flags.

Infantry formations

As early as 1939, a massive expansion of the Red Army was put in motion, owing to the increasing international tensions. Although the emphasis in mobile warfare lies on the mechanized formations, yet the majority of the Red Army still consisted of infantry units, in 1939, some 65% of the total of ground forces. Due to Stalin’s cleansing, far too few officers were left over who could train and lead them in a professional way.

On August 16, 1940, it was decided to revise the existing plans for mobilization. A special commission was installed, chaired by Alexandr M. Vasilevsky, member of the general staff. The new plans became known by the name of MP-41 (Mobilization Plan 41) and would continuously be adapted in the course of 1941. MP-41 entailed a secret process of mobilization where a limited number of reservists were drafted under the guise of training maneuvers which was put in motion in 1941, far too late. When German troops invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, the Red Army had only 2,901,000 men under arms in the western military districts.

On paper a Soviet division was almost equal to a German infantry division with a total of 4,483 men, split into three regiments of three battalions, two artillery regimens, a battalion of light tanks and supporting units. In 1941 however, the Fuselier divisions were highly undermanned and generally consisted of less than 8,000 men under arms. As in May 1941, 800,000 reservists were called upon, the divisions were supplemented piece-meal but these reservists lacked experience. In June 1941, a Soviet army consisted of three Fuselier corps, each of them made up of two to three Fuselier divisions. In fact, a Soviet army in 1941 consisted of only six to ten divisions, supported by an undermanned mechanized corps and with a huge shortage of supporting and communication units.

Additional ground forces

The Soviet forces facing the Germans in 1941 were not only made up of regular army units. On the borders, special units of the Russian security service, NKVD Narodniy Kommissariat Vnutrennikh Del were deployed; lightly armed forces mainly tasked with border protection, comparable to the modern customs. These units were directly answerable to Moscow and the commanders of districts and the army were kept out of this structure. The Soviets also had a special unit within the armed forces, the POV Strany Voiska Protivovozduchnoi Oboroni. It was responsible for the manning the anti-aircraft defense around the cities and strategically important targets like airports. It even had its own air force at its disposal.

The Red Air Force

In June 1941, the Soviet Air Force RKKVF, Raboche Krestyanskaya Krasnaya Armia was the largest air force in the world in terms of numbers, 19,533 aircraft of which 7,133 aircraft were based in the western military districts. The majority of the planes however was hopelessly outdated and the cleansing of the officers’ corps had also had disastrous consequences for the Red Air Force. Talented and progressive designers had also been cleansed by order of Stalin.

The better part of the Soviet fighters consisted of the Polikarpov I-16 which was no match at all for its German opponent, the Messerschmitt Bf 109. In June 1941, biplanes like the Polikarpov I-15, I 152 and I-153 were still in service in the Red Air Force. Along with the decision to renew the equipment of the Red Army, large scale reforms were also put in motion in the Red Air Force.

At the end of the thirties, Russian designers had started developing modern monoplanes like the Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG 1 which would ultimately evolve into the Mig-3. In the spring of 1941 the Lavochkin LaGG- and the Lavochkin LaGG-3, made entirely of wood, began entering the squadrons. The Yakovlev Yak-1 and the Yak-3 were also distributed in small numbers among the Soviet fighter regiments. Production of new aircraft progressed slowly however and there was a shortage of pilots to fly these new aircraft.

The bombers of the Red Air Force were hopelessly outdated as well; the most aircraft in service were the Tupolev SB-2, the Sukhoi SU-2 and the Ilyushin Il-4 (DB-3F). In 1940, production of the new and improved types which would distinguish themselves later in the war, like the Petlyakov PE-2 and the formidable Ilyushin Il-2 Shturmovik, progressed slowly however. Hence, in June 1940 only a few of these aircraft were available. The bomber squadrons also severely lacked trained crews to fly these new planes. Moreover, the majority of the aircraft was not even equipped with radio.

Due to the expansion of territory to the west, new airfields were to be constructed. In June 1941, only a few air bases were fully operational. The majority of the aircraft was still parked in the open air as there were too few hangars to hide the planes from the spying eyes of the Luftwaffe and protect them from the weather. The air bases also suffered from a huge shortage of anti-aircraft guns.

Command of the Red Air Force was very confusing as well. Some air divisions were tasked with supporting ground forces (armies and fronts), others were directly commanded by the general staffs while still others were allocated to a command structure of regional air defense (PVO). The Red Air Force lacked a coordinated command structure which made it difficult to realize a combined deployment of air and ground forces. Moreover the existing tactics were hopelessly outdated.

The Red Navy

The Red Navy ( RKKF= Raboche Krestyanskaya Krasnaya Flot ) had also suffered heavily from the cleansing in its command. Just like the ground forces, the Red Navy embarked on large scale reorganizations in 1940. The traditional ranks from the Czarist era, those of admiral and vice-admiral, were reinstated.

The Red Navy was responsible for the defense of the Baltic Coast (the Baltic Fleet based in Kronstadt), the coast in the extreme north (the Northern Fleet based in Murmansk) and the Black Sea Fleet, based in Sevastopol responsible for the defense of the Russian coast on the Black Sea. Due to the annexation of the Baltic states, the navy gained a number of new bases which improved her position, strategically speaking, to take on the Kriegsmarine in the Baltic in the event of war. It was compelled however to develop a defensive strategy in case of a war with Germany. The better part of the production facilities was allocated to the construction of submarines. The Red Navy, by the way, did have its own air and ground forces to defend its home bases and to undertake amphibious landings.

The Soviet Union was invaded on June 22, 1941 at a time when she was in fact at her weakest. The huge shortage of well-trained officers, the fear to deploy own initiatives which resulted from the cleansings, the halfhearted mobilization and the lack of modern means of communications contributed for a large part to the disastrous defeats suffered by the Red Army in the first year of the German-Russian war.

Definitielijst

- brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- cavalry

- Originally the designation for mounted troops. During World War 2 the term was used for armoured units. Main tasks are reconnaissance, attack and support of infantry.

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

- Fuselier

- In World War 2 the name of an infantry man armed with a rifle in, among others, the Dutch and Belgian armies. The soldiers of the Dutch guards regiment “Prinses Irene” are still called fusiliers.

- infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Kriegsmarine

- Germa navy. Part of the Wehrmacht next to Heer and Luftwaffe.

- Luftwaffe

- German air force.

- Marshal

- Highest military rank, Army commander.

- mobilization

- To make an army ready for war, actually the transition from a state of peace to a state of war. The Dutch army was mobilized on the 29 August 1939.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- Reichswehr

- German army during the Weimar republic.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- revolution

- Usually sudden and violent reversal of existing (political) the political set-up and situations.

- RKKA

- Official name of the Red Army, the army of the Soviet Union. In full “Rabotsje Krestjanskaja Krasnaja Armiya”, meaning Red Army of workers and peasants.

- RKKF

- Official name of the Red Fleet, the fleet of the Soviet Union. In full “Rabotsje Krestjanskaja” meaning Red Fleet of workers and peasants.

- RKKVF

- Official name of the Red Air force, the air force of the Soviet Union. In full “Rabotsje Krestjanskaja Vozdoesjny Flot”. Meaning, Red airfleet of workers and peasants.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- strategy

- Art of warfare, the way in which war should be conducted in general.

Soviet plans for defense

The Soviet plans for defense prior to the German invasion have been the subject of heated arguments and discussions for decades. Stalin had been informed about the imminent German invasion by dozens of sources and it is therefore hardly imaginable that the Red Army was overwhelmed as it was in the early stages of Operation Barbarossa. There was however more than one cause for the disaster that struck the Soviet Union in June 1941. This catastrophe was a confluence of events in which Stalin’s personal intervention played a significant role.

Just like German after the First World War, the Soviet Union found itself in an isolated position at international level. In Europe, there were few governments that had cordial and open diplomatic relations with the Soviets and as international tension was mounting halfway through the thirties, a start was made with the development of plans for defense and mobilization.

The first detailed plans for defense

As early as 1935, Marshal Mikhail N. Tukhachevsky recognized the danger of the threat emanating from Nazi Germany. One year later he proposed to the general staff to organize special war games to investigate what the situation would be in case of a German invasion. Tukhachevsky envisaged a joint invasion by Germany and Poland in which troops would be concentrated north of the Pripjat marshes in order to advance on Moscow via Smolensk. In hindsight, an alliance between Germany and Poland seems unlikely, given the fact that Germany and Poland had signed a non-aggression pact in 1934. Based on the results of the investigation, Tukhachevsky declared in early 1934: ‘Operations will inevitably be more intense and fiercer than during the First World War. At that time the fighting on the borders in France took just two days. Now, offensive operations in the first stages of a war may last for weeks. The Blitzkrieg the Germans continuously boast about in their propaganda, can only be expedient if the opponent lacks the will to strike back. Should the Germans meet an opponent who takes the initiative, the entire course of the situation will change.’

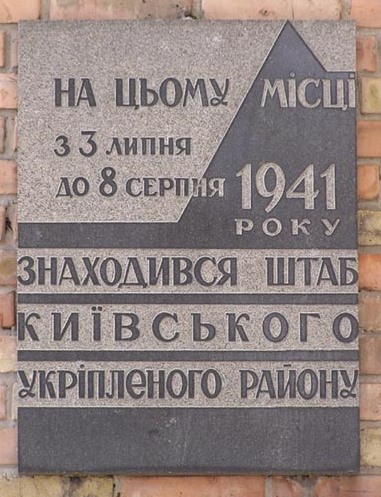

Based on these findings, Tukhachevsky developed a plan for defense in cooperation with the general staff. The first echelon should be deployed on the borders, the so-called shield. This first echelon should consist of so-called ‘fortified regions’ UR= Ukreplenny Raion , predominantly made up of infantry. These regions were tasked with absorbing, delaying and ultimately halting the enemy offensive. The second echelon, the ‘secret operational groups’ would be made up of a combination of mechanized corps and shock troops. The second echelon, designated the hammer by Tukhachevsky, was to launch a massive counter attack once the first echelon had delayed the enemy offensive, expel the enemy from Soviet territory in order to annihilate him on the other side of the border.

Based on this strategy, the Red Army was being prepared for war. Fortified regions were established on the western borders of the Soviet Union. This line of defense would become known as the Stalin line. However, six months after Marshal Tukhachevsky had drafted his plans for defense, he was executed along with his most prominent associates. This was the beginning of the wave of terror that would cripple the Red Army.

Dismantling the Stalin line

After the officers’ corps had been decimated and the tension in Europe was mounting, Hitler and Stalin signed a non-aggression pact, the notorious Molotov-Von Ribbentrop Pact. In a secret clause of the pact, Eastern-Europe was divided between the two totalitarian powers. With this pact, Joseph Stalin attempted to keep the Soviet Union out of the war and by annexing the Baltic states to create an additional buffer zone. The occupation of Eastern-Poland and the annexations in the Baltic meant that Germany and the Soviet Union shared a common border, actually making the Stalin line redundant. After the borders had been redrawn hundreds of miles to the west, the fortifications on the Stalin line were also dismantled and the Red Army took up defensive positions on the new borders. All this meant that the existing plans for defense had to be revised.

Von Ribbentrop bids goodby to Molotov after his visit to Berlin, November 14, 1940 Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-1984-1206-523 / CC-BY-SA 3.0

Contrary to Stalin’s expectations, the Germans overwhelmed the Benelux and France in May and June 1940. The Soviets had seriously reckoned with the possibility that the war in the west would turn into a battle of attrition but instead, it ended in a lightning German victory. In July 1940, the general staff hastily started to revise the plans for defense, designating Germany as the most probable potential opponent. The staff named the region north of the Pripjat marshes as the most likely location were the Germans would concentrate their main force.

In the meantime, Stalin had to prevent the Soviet Union from entering into a conflict with Germany at all costs. On November 12, 1940, People’s Commissioner of Foreign Affairs, Vyacheslav M. Molotov paid a visit to Berlin to negotiate with Hitler and Von Ribbentrop. Molotov reacted reluctantly to a German proposal to sign an agreement between the Soviet Union and the members of the Axis powers. Molotov voiced Stalin’s concern about the German intervention on the Balkans and in Finland and demanded guarantees and concessions from the Germans. Moreover, Molotov asked for permission to establish naval bases in the region of the Bosporus and the Dardanelles, giving the Soviet Union control over the passage to the Black Sea. The negotiations proceeded awkwardly and Molotov eventually returned to Moscow empty-handed. These were the first clear indications that tensions between the two super powers were mounting.

Information about German plans

As early as January 1941, agents of the GRU, Glavnoye Razvedivatel' noye Upravlenye , the Soviet military intelligence service, were collecting information on Hitler’s intentions and German troop movements to the east. The NKVD also had its own department which occupied itself exclusively with gathering information, the GUGBEZ Glavnoye Upravlenye Gosudarstvennoi Bezopasnosti . This organization had established a vast network of spies in Nazi- occupied Poland and Czechoslovakia and was well aware of the German build-up of forces on the borders. But indications also flowed into Moscow from foreign countries as to Hitler’ s intention to attack the Soviet Union. From Washington, London and Stockholm Stalin was alerted to a German surprise attack in the coming spring.

Later that month, secret war games were held to test the existing defensive plans. The plan submitted to Stalin by the chief of the general staff, Kirill A. Meretskov, probably did not meet expectations and Meretskov was relieved of his function as he reckoned with a German attack north of the Pripjat marshes. He was replaced by the young, gifted but aggressive army commander Gheorghy K. Zhukov because Meretskov envisaged a German attack north of the Pripjat marshes. Just like Marshal Semyon K. Timoshenko and General Zhukov, Stalin was convinced that the main body of an eventual German invasion would be launched south of the Pripjat marshes. They assumed Hitler was targeting the rich grain fields and industrial areas in the Ukraine. This meant that Soviet strategy had to be revised entirely. Zhukov was given the task to work out the defensive plan and to coordinate the required troop movements.

People’s Commissioner of Defense Marshal of the Soviet Union S.K. Timoschenko (left) and chief of the general staff General G.K. Zhukov Source: Public domain

State plan for defense 41

General Zhukov quickly went to work on State Defense Plan 41 (DP 41). He referred to the old and trusted defense plans of Marshal Tukhachevsky who had been executed. In the opinion of the new chief of staff, the all decisive fighting on the border should take 10 to 15 days. During these engagements, the Red Army should adopt a defensive tactic in order to subsequently launch a massive counter attack after which the battle should proceed west of the border. As Tukhachevsky had already proposed in the thirties, two echelons were established. The majority of the divisions should be deployed in the forward belt of defense, the shield, in particular in the Special Baltic Military District (Colonel-general Fyodor I. Kuznetsova), the Special Western Military District (Colonel-general Dimitry G. Pavlov), the Special Military District Kiev (Colonel-general Mikhail P. Kipronos) and the independent 9th Army (Lieutenant-general Cherevichenko). As soon as the war broke out, these would be renamed the Northwestern Front, the Western Front, the Southwestern Front and the Southern Front respectively. The first belt of defense should be deployed in three defensive lines along the new borders. The first defensive belt (in total 57 divisions) would consist of lightly armed infantry formations and NKVD border troops while the second belt (52 divisions) and the third belt (62 divisions) were made up of shock troops and mechanized corps to launch local counter attacks. The second strategic echelon (the hammer) would consist of 57 divisions, spread over five armies which were deployed along the banks of the Dnepr and the Dvina. It was tasked with launching the great counter offensive in collaboration with the second and third defensive belt of the first echelon. The German intelligence services were not aware of this second echelon though and once the Germans had penetrated in the hinterland of the Soviet Union, this turned out to be an unpleasant surprise.

Warnings once more against a German attack

Warnings about an imminent German invasion kept flowing into Moscow. It was even reported that the Germans would attack on May 15, 1940. These warnings resulted in stepped-up Soviet efforts to prevent a war. Various messages were sent to Berlin indicating that the Soviet Union would stick to the non-aggression pact. Stalin even used a non-aggression pact with Japan on April 13, 1941 to stress that friendship with Germany was guaranteed.