Walter Süskind (1906-1945)

Preface

The activities of the Jewish Council during the occupation of The Netherlands in the Second World War are controversial. At the command of the Germans they actively participated in the deportation of their own people. The discussion to what extent this deed can be justified ethically, is endless.

Walter Süskind was one of the employees of the Jewish Council. True, he had an important role at the organization of deportations, but at the same time he saved the lives of hundreds of people, of which mostly children. He did this without consent or without knowledge of the management of the Jewish Council and at the risk of his own life. During the war, many Jews saw him as a traitor, but behind the mask of the pretended collaborator was in reality hiding a hero.

Before the war

Walter Süskind was born on the 29th of October 1906 in Lüdenscheid, Germany. According to journalist Elma Verhey, his mother was Jewish-Orthodox, while his father was a bit more liberal. Besides Walter, the married couple Süskind had three more sons. The family was poor, but nevertheless, they had also adopted an orphan boy within their family.

Until 1938, Walter Süskind exercised a high ranking job position at soap producer Lever Brothers in Germany. Together with the Dutch Margarine Unie, this company formed the multinational Unilever since 1930. Meanwhile, Adolf Hitler came into power and anti-Jewish measures followed rapidly. In 1938, Süskind lost his job because he was Jewish. Because he was partly of Dutch descent and had a Dutch passport at his disposal, he decided to flee Germany and to immigrate to The Netherlands. Together with his wife, Johanna Süskind-Natt, he settled down in Bergen op Zoom. Here, their daughter Yvonne was born on the 28th of March 1939. Also in The Netherlands he was successful in business. “He was a personality and an easy talker”, explained his cousin Bernard Süskind. “As soon as he had made friends and people became his client, they stayed loyal to him.”

Persecution of the Jews in The Netherlands

On the 10th of May 1940, German troops invaded The Netherlands. The Dutch army surrendered on the 15th of May and the country was then occupied. The continuing years after, also the Jews in The Netherlands were hit by the Nazi's anti-Semitic policy. In the beginning, it concerned mostly measures which were aimed at the registration and identification of Jews. To make Jews more recognizable, from the 23rd of January 1942, they had to have a 'J' stamped in their identity card. A few months later, on the 2nd of May, they were obliged to wear a Jewish Star. In Amsterdam the Jews' quarter was closed. In this quarter, Jews from Amsterdam and its environs were concentrated during the period 1941-1943.

In February 1941, the so-called Jewish Council was called into life by order of the German occupying force. This Jewish governing council was the contact person between the Jews and the occupying force and was responsible for pushing through the imposed anti-Semitic measures. From the summer of 1942, the council coordinated the deportation of the Jews. The majority of the Jews in The Netherlands ended up in the concentration and destruction camps of Nazi-Germany through camp Westerbork. Approximately 107.000 Jews in total were deported from The Netherlands, of which approximately 102.000 were killed by the Nazi's.

Süskind had again lost his job due to anti-Semitic laws in 1942 and was obliged to move with his family to Amsterdam. Since March 1942, he lived here at the Nieuwe Prinsengracht. He was appointed manager of the Dutch Theater by the Jewish Council, the former theater at the Plantage Middenlaan where from August 1942, the Jews in Amsterdam were collected before they were deported to camp Westerbork. Süskind was particularly working for the Expositur, the part of the Jewish Council which served as a connecting office between the Council and the Zentralstelle für jüdische Auswanderung. This last mentioned German bureau was part of the Sicherheitspolizei and the Sicherheitsdienst and was in charge of the deportation of the Jews from The Netherlands. It was under the command of SS-Hauptsturmführer Ferdinand Aus der Fünten.

'Hollandsche Schouwburg' (Dutch Theater)

As manager of the 'Hollandsche Schouwburg', Süskind was responsible for the daily course of things in the building and the coordination of the intake. He was in control of the Jewish staff which consisted among them of doctors, nurses, cleaners and employees of the so-called department 'aid to departees'. While performing his tasks, Süskind was in direct contact with the German staff of guards. His understanding with them was simplified by his fluent command of the German language and knowledge of the German culture. Also with his open and friendly nature and the ease at which the former business man made contacts, he won their trust. He even became friendly with some Germans, of which Ferdinand Aus der Fünten. “Walter Süskind acted as if he knew Aus der Fünten from his past in Germany”, says the Dutch Holocaust survivor Ries van der Pol. “He acted as if he was happy to see an old friend of him. And apparently, Aus der Fünten bought it.” Many eye- witnesses remember that the Jewish business man and the SS-officer got drunk together.

Süskind's friendly acquaintanceship with the Germans raised suspicion among many other Jews. They considered him as a traitor. What they did not know, was that Süskind was the pivot of an underground organization. He associated with the Germans in an engaging manner to win their trust. “Aus der Fünten trusted him”, says Sieny Cohen-Glasoog, a nanny in the crèche across the 'Schouwburg'. “He could not believe that a German, even though it was a German Jew, would betray him. But he did.” Süskind's trustworthy position was a disguise by which he concealed that he was involved in the escape of Jews from the 'Hollandsche Schouwburg'. Together with a few others, of which the Amsterdam economist Felix Halverstad, he took care of the disappearance of their cards from the filing cabinet and “everytime when their was another transport to Westerbork,” write the NIOD-employees Erik Somers and René Kok in their book “Nederland en de Tweede Wereldoorlog”, “Süskind stood next to the SS-guard to distract him. Meanwhile Halverstad was counting out loud at the other side of the exit: 182, 183, 184, 195, 196,... etcetera. In that way, another ten could escape.” After they escaped from the 'Schouwburg', they could go into hiding elsewhere.

Resistance in the crèche

Süskind became, however, mostly famous for his efforts at saving the Jewish children from the crèche across the Theater. At the arrival in the Theater, children younger than 16 years were separated from their parents and adopted in this crèche. Also Jewish orphan children and children in hiding who were caught by the Germans, ended up here. The children were put under the good care of the Jewish nanny's under the guidance of Henriëtte Pimentel. Like Süskind, she was a central figure in the organization of saving the children from the crèche. “Mrs. Pimentel gets all honor from me for what she has done there”, says Sieny Cohen-Kattenburg, who was also involved in the rescue operation as a nanny. “She was always busy saving children. She brought them everywhere. That was very impressive.” Süskind and Mrs. Pimentel were helped by several people, among them the nanny's, but also by non-Jewish resistance fighters, of which a lot of students.

Before the rescue operation could be started, it was firstly necessary to decide which children should be saved, because it was impossible to save them all. Süskind and his helpers judged which children were considered for rescue. In doing so, it was among other things important to judge if the parents were able to handle the rescue operation and keeping it a secret. Subsequently, the parents were asked if they were willing to hand over their child, in order to put the child in safety. “When you hear this as a parent, you have to think about it”, says Sieny Cohen-Kattenburg. “So we gave them a few hours to think. […] Some said: yes, let's do that. It will not last for long, so if you have a good place, bring him or her along.”

The next step was that the personal data of the children had to be destroyed. The file cards of the children had to be deleted from the filing cabinet as well as from the Theater as from the Zentralstelle für jüdische Auswanderung. With this, Süskind was helped by Felix Halverstad. He was also responsible for the forgery of identity cards for the adult Jews which escaped from the Theater. After the names of the to be rescued children were not present anymore in the archives, the rescue operation could be continued. During the history of the crèche, children have been smuggled away from the crèche in several ways. Like this, it happened that the older children got the instruction to escape during a walk, after which they were taken care of by resistance members. The younger children were, among others, brought to the next to the crèche situated 'Hervormde Kweekschool' through the backyard. From there, they were taken away in backpacks, shopping-bags, laundry-baskets and empty milk-cans. During other escapes was made use of the tram which drove along the crèche. When the tram stopped, the SS could not see the crèche anymore. They did not notice that the resistance members stepped into the tram with a child from the crèche. The succeeding of all these different rescue-methods was mostly owed to the fact that the crèche, in contradistinction to the Theater, was not guarded by the SS.

After the children were 'smuggled away' from the crèche, they were accommodated at foster-families which were found throughout the whole country, but mostly in Limburg and Friesland, with the help of the Dutch resistance. Many children lost their parents and also stayed with their foster-parents after the war. It is estimated that in the period of April 1942 until September 1943, 600 to 1.100 children were saved by the resistance-group around Süskind. The rescue operation has never been noticed by the Germans, although Kok and Somers notice that Süskind and Halverstad “were brought before the Sicherheitsdienst a few times to account for their behavior on the suspicion of assisting escapes. One time Süskind even got arrested, but thanks to the fact that he spoke German fluently and his trustworthy appearance, he managed to rescue himself from the situation.”

End of the resistance operation

On the 29th of September 1943, the last razzia took place in Amsterdam. Now that the capital city was declared “Judenrein” (free of Jews), the Jewish Council was dissolved. Also the crèche was closed. Because there were still Jews being arrested who were hiding, the 'Schouwburg' stayed open until the last transportation on the 19th of November 1943. Henriëtte Pimentel had been deported to transit camp Westerbork together with the children from her crèche, in July 1943. Subsequently, she was sent to Auschwitz where she died at the 17th of September 1943.

Meanwhile, the wife and daughter of Süskind already resided for a few months in Westerbork. Walter Süskind had been reunited with them here, but shortly returned to Amsterdam, because he had convinced the Germans that he still had to do important work here. During the short period that he returned to Amsterdam, he continued his resistance work, of which the manufacturing of false certificates of birth and false statements of mixed marriages. He even developed a plan to liberate Westerbork with the help of some strong-arm boys, but this was never put into practice. When he heard that his arrest was coming, he had the possibility, like a lot of his staff, to go into hiding with the help of the resistance. However, he decided to return to his family in Westerbork and returned in the transit camp as a penal prisoner in September 1944. The Jewish Historic Museum mentions that there he wanted to organize resistance actions and escapes again, which brought him into conflict with the camp leaders. This would have accelerated his deportation.

From Westerbork, the family Süskind was deported to Theresienstadt with the last transport on the 3rd of September 1944. This was formally a ghetto for privileged Jews, but in reality a lot of Jews died here and for others it formed a portal for the destruction camps in Poland. Also here, Süskind is said to have made efforts for the Jewish orphan children which resided here. He also tried to save his own family. He had a letter in which Aus der Fünten stated that the former manager of the 'Hollandsche Schouwburg' was a good Jew, but presumable he had never been able to show it to Karl Rahm, the commander of Theresienstadt. According to Jacques Presser, the writer of “Ondergang” about the persecution of the Jews in The Netherlands, professor David Cohen, the former leader of the Jewish Council in The Netherlands, has “prayed and begged” at the Judenälteste in Theresienstadt, Benjamin Murmelstein, to put in a good word for Süskind with the camp commander. According to Presser, Murmelstein refused this. Subsequently, the historicist writes that Süskind and his family could hide for a few days in the Hamburg barrack, the part of Theresienstadt where, since 1943, mostly Dutch prisoners were accommodated.

Riddles about his decease

Süskind could eventually not prevent that he and his family were deported to Auschwitz. They arrived here on the 25th of October 1944. His wife and daughter were immediately gassed by arrival. He himself was selected for forced labour and died according to most sources on 28 February 1945 at the age of 38. For the location of his dead is given “somewhere in Central Europe”. How he died, is unclear. One version is that he died during a death march. When the Soviets approached Auschwitz closer, the majority of the prisoners were evacuated by foot. Large amounts of prisoners died during these dead marches due to the cold and exhaustion or were shot dead by a guard.

Another version is that he was killed in Auschwitz by other Dutch prisoners. Only a few people knew about Süskind's resistance work. The majority of the Dutch Jews who knew him from the 'Schouwburg', saw him as the person who was in charge of the deportations and hated him for this. Another version originates from Kok and Somers, who describe that Süskind perhaps died immediately at arrival in Auschwitz, because he chose to stay with his wife and daughter, probably knowing that they (and therefore also himself) would be gassed.

After the war

After the war, it was announced that Süskind was not a traitor, but that he tried more than the most employees and members of the Jewish Council, to save people. Similar resistance against the German policy was strongly discouraged by the management of the Jewish Council and did hardly or not take place from the ranks of the Council. A witness brought forward by historicist Lou de Jong, stated about this: “This work occurred entirely at own risk and was not stimulated by the management of the Jewish Council. On the contrary, in case the management of the Jewish Council would have known this officially, they would have prohibited this out of fear”.

In honour of Süskind's heroic action, a wooden drawbridge in Amsterdam is named after him in 1972. It concerns the bridge over the Nieuwe Herengracht, near the Waterloo square where in 1941, Jewish youngsters fought with Dutch Nazi's. On a copper tablet is written: “During the German occupation he withdrew many Jewish fellow citizens from deportation at the risk of his own life”.

Definitielijst

- ghetto

- Part of a town separated from the outside world to segregate Jewish population. The establishment of ghettos was intended to exclude the Jews from daily life and from the rest of the people. From these ghettos it was also easier to deport the Jews to the concentration and extermination camps. Also known as “Judenviertel” or Jewish quarter.

- Holocaust

- Term for the destruction of European Jewry by the Nazis. Holokauston is the Greek term for a completely burnt sacrifice.

- Jewish Star

- Star of David on a yellow background which had to be worn by Jews in Nazi Germany and occupied territory during World War 2.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- persecution of the Jews

- "Judenverfolgung", action imposed by the Nazis to make life hard for the Jews, to actively persecute them and even annihilate them.

- razzia

- Organised round-up of a group of people. This could be Jews but also persons in hiding or other groups.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Theresienstadt

- City in the Czech Republic. Here the Nazis established a model concentration camp.

Images

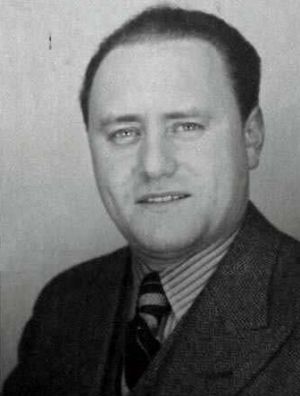

Walter Süskind. Source: Jüdisches Historisches Museum.

Walter Süskind. Source: Jüdisches Historisches Museum.Information

- Article by:

- Kevin Prenger

- Translated by:

- Ivita Kops

- Published on:

- 19-01-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Sources

- DR. J. PRESSER, Ondergang, Staatsuitgeverij, Den Haag, 1965.

- JONG, L. DE, Het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden in de Tweede Wereldoorlog 6, Staatsuitgeverij, Den Haag, 1969.

- JONG, L. DE, Het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden in de Tweede Wereldoorlog 7, Staatsuitgeverij, Den Haag, 1969.

- KOK, R. & SOMERS, E., Nederland en de Tweede Wereldoorlog, 2005.

- Joods Historisch Museum

- Verzetsmuseum Amsterdam

- Joods Monument

- Holandsche Schouwburg