Introduction

Closely interwoven with the history of the persecution of the Jews during World War II in the Netherlands is transit camp Westerbork. During the war it was officially referred to by the Germans as Polizeiliches Judendurchgangslager Westerbork. More than 101,000 Dutch Jews were deported via this camp to the concentration and extermination camps of the Third Reich. Only a small part of them survived the Holocaust and returned to the Netherlands after the war.

There’s a history to be told about the period that the camp functioned as a transit camp, because camp Westerbork was not set up by the German occupiers, it already existed before the war. The camp was built in 1939 by the Dutch government as a refugee camp for Jewish refugees from Germany and Austria.

In this article we will discuss both the history of the Central Refugee Camp Westerbork (1939-1942), as well as the history of the transit camp (Polizeiliches Judendurchgangslager) Westerbork (1942-1945). The history of the persecution of the Jews in the German-occupied Netherlands is the thread of this article. Besides this, attention will be given to the allocation given to the Westerbork camp site after the war.

Definitielijst

- Holocaust

- Term for the destruction of European Jewry by the Nazis. Holokauston is the Greek term for a completely burnt sacrifice.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- persecution of the Jews

- "Judenverfolgung", action imposed by the Nazis to make life hard for the Jews, to actively persecute them and even annihilate them.

Images

Part of the 102.000 Stones monument at Camp Westerbork. Source: Bureau Funeralia / René ten Dam.

Part of the 102.000 Stones monument at Camp Westerbork. Source: Bureau Funeralia / René ten Dam.Creation

From the moment that Adolf Hitler came into power in 1933, life for the Jews in Germany became less worthy. In the years before the war, many Jews fled from Germany to escape the oppression and humiliating policy with regards to Jews. After the Anschluss from Austria on 13 March 1938 – as a result of which also the Austrian Jews had to deal with the Nazi suppression – and the Kristallnacht (Chrystal Night) of 9-10 November 1938, a huge stream of Jewish refugees came flocking in from the German Reich. There were hardly any countries left, willing to take on more Jews and so a serious refugee issue arose.

One of the havens of refuge for German and Austrian Jews was the Netherlands. In 1933, it was still relatively easy for them to be allowed to enter the country. The only requirements which were laid down in the immigration law from 1849 were that immigrants had to dispose of sufficient social securities and they had to have valid documents. Because of the developments in Germany, the Dutch government was afraid of a large stream of refugees and therefore adopted a new law on 16 May 1934. In it, labour was connected to a special permit system. This made it almost impossible for refugees to enter employment. On 30 May 1934 the Dutch government also announced that refugees with the German nationality had to be barred as much as possible.

Despite the policy to bar as much refugees as possible, about 25,000 German-Jewish refugees came to the Netherlands between 1933 and 1938. Many of them only used the Netherlands as a temporary place of residence on their way to a final destination. The rules even became more stringent, when on 7 May 1938, it was determined that not a single refugee would be allowed to enter the country. Yet, after the Kristallnacht more than 40,000 Jews tried to obtain a visa for the Netherlands. Initially, the Dutch government rendered no assistance, but eventually 7,000 Jews were admitted, and later an additional 2,000 refugees due to humanitarian reasons.

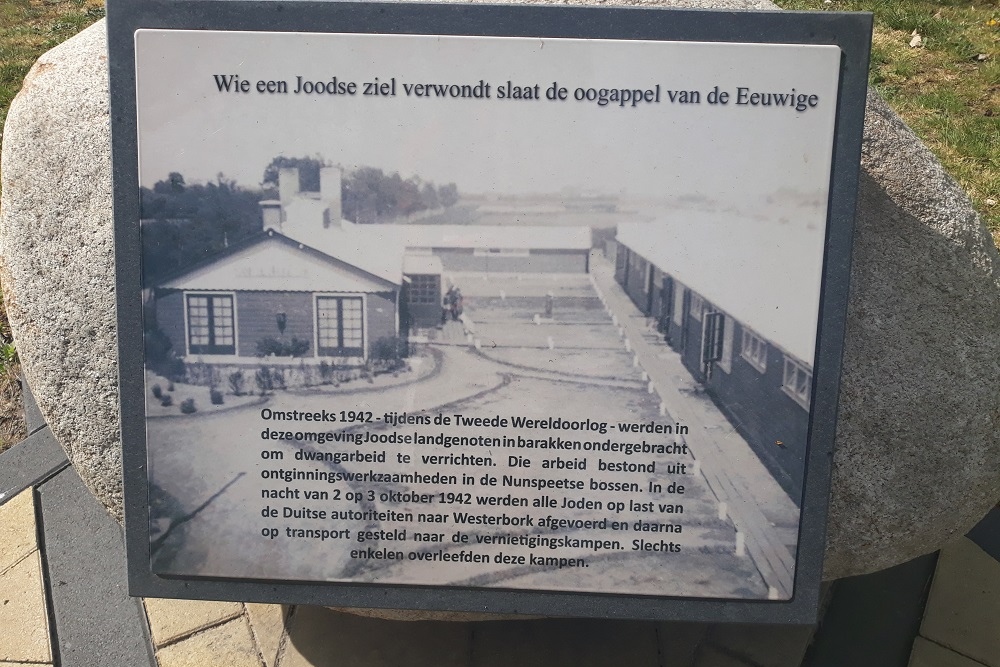

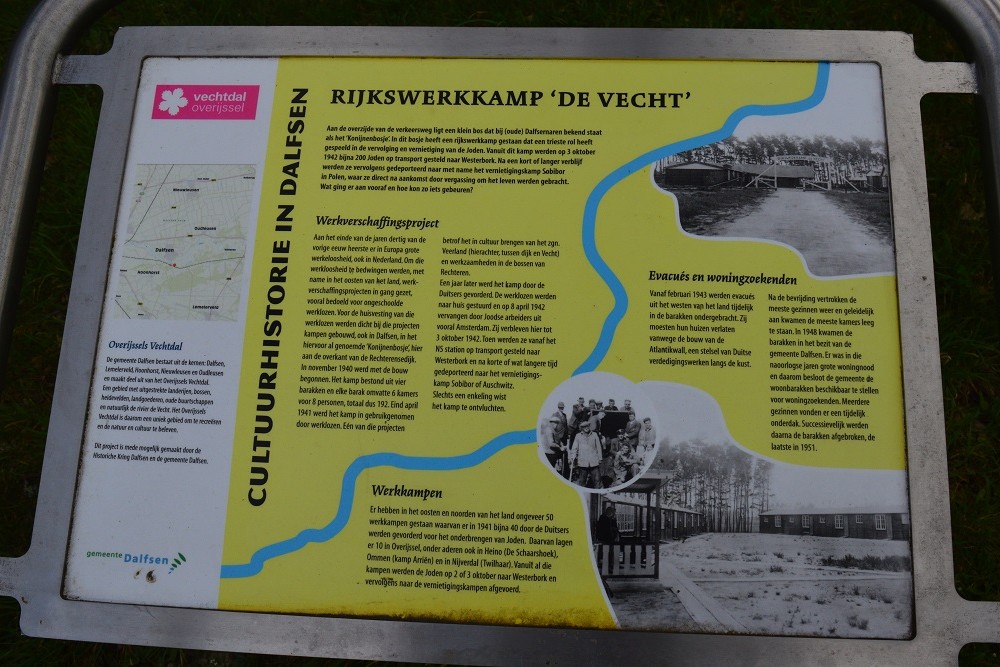

The refugees were received in reception camps and relief centres across the Netherlands. Some Jewish refugees ended up in work villages, such as work village Wieringermeer, nearby the town Nieuwesluis. The refugee aid was mainly organised and financed by private individuals and the Committee for Jewish Refugees – a political organisation in which several Jewish groupings worked together to find a solution for the Jewish refugee problem. In February 1939, the fourth government Colijn decided to accommodate all Jewish refugees from Germany in one camp. At first, they wanted to set up this refugee camp on a site nearby Elspeet on the Veluwe. This site was miles away from civilization, preventing the refugees from integrating with the Dutch society – exactly what they wanted.

However, Elspeet as first choice of location for the refugee camp did not go down well with several parties. The Algemene Nederlandse WielrijdersBond (ANWB) (the Royal Dutch Touring Club) was of the opinion that a refugee camp on this location would affect the scenic beauty and attractiveness of the area for tourists. Local residents also protested. But it was the protest letter of one resident in particular that made a big impression. Through her secretary, Queen Wilhelmina informed the Minster of Foreign Affairs "that she regretted the fact that this site was chosen as the location for the refugee camp, so closely located to the summer house of Her Majesty and that it would be much more pleasant that – given the fact that it should be located in the Veluwe area – another location would be much more suitable. That is a location much further away from Palace Het Loo." Despite the fact that the location of the camp was as much as 12 kilometres from Palace Het Loo "Her Majesty (…) would appreciate it, if a new location (…) could be found". And so it was clear: another location had to be found for the refugee camp.

In the end, the choice was made to locate the camp in Drenthe, a province with many heaths. In the vicinity of the town Westerbork, the Dutch Forestry Commission managed a desolated piece of heath that was an ideal location for the refugee camp. A member of parliament that visited the camp in 1938, called the site "an extremely dreary plain, probably one of the most depressing parts of land in the Netherlands". Not all of the residents of Westerbork were enthusiast about the plans, but the camp would be located far from the town centre and local shops would profit from extra revenue. Even the Jewish community was initially content with this choice of location. Despite the fact that they had to pay the costs of around 1.25 million guilders, they didn't have a say in the matter. Because they did not find the gloomy location suitable for young children and elderly, the Central Committee for Special Jewish Matters and the Committee for Jewish Refugees which was part of it, only agreed to the location if the refugees of this special age group would be accommodated at better locations. This condition was met by the Dutch government. The enthusiasm of the Jewish organisations was further stimulated by making all sorts of promises: the barracks in the camp would be equipped with central heating and excellent sanitation. A synagogue and school would also be built and the Dutch government promised to provide recreational facilities.

For the time being, the Central Refugee Camp Westerbork was intended for young, vital Jewish refugees who wanted to immigrate to Palestine. For these pioneers, the wasteland of Westerbork, where they would farm, was an excellent preparation for their future. Here, they would be educated to prepare for their emigration to Palestine. The camp was placed under supervision of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In the summer of 1939, the workers started with building the living barracks.

Definitielijst

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- synagogue

- Jewish house of prayer.

Images

A Jewish synagogue goes up in flames during the Crystal Night. Source: USHMM.

A Jewish synagogue goes up in flames during the Crystal Night. Source: USHMM.Pre-war years

On 9 October 1939, the first German-Jewish refugees arrived at the Central Refugee Camp Westerbork. "The mood was great, a nice pan of soup was available", as camp director D.A. Syswerda described their arrival. "The barrack was ready for their arrival and left a good impression, thanks to the fine beds and beautiful blankets. That same night, it was reported that things weren’t so bad in the new camp." The opinion of the new inmates was less positive, however. "The further we got the more solitary it became", remembered Werner Bloch. "At one point, all you could see were heaths with here and there some bushes. At the location where eventually the refugee camp would be, was a huge plain with only heath and sand. A desolate site. But we had to put up with it."

Although the Jewish refugees in Westerbork were safe for the time being and they therefore settled for this place of refuge, the stay was not particularly pleasant. Especially the townspeople had to adjust enormously to the living conditions on the bare plain with harsh winds. During winter time it would be very cold and in the summer, the camp inmates were often bothered by heat, flies and sand storms. The location of the central kitchen was not really central and it was therefore difficult to deliver the meals without them going cold. The camp inmates had to work very hard. They were deployed at building works and for cultivating the surroundings. Land had to be cultivated in order to build a farm, so that the inmates could provide their own food supply.

The promises about schooling and recreational provisions made by the Dutch government, were hardly fulfilled. The barracks were not equipped as promised and still had to be furnished. Luckily there was central heating. "It wasn’t that bad", told camp resident Ruth Blumenthal after the war. "We had a small kitchen with a counter and a sink and one gas appliance with one burner. (…) We also had a bathroom with a toilet and a washbasin. There was no bath or shower (…) but there was a bathhouse in the camp." Excursions outside the camp were possible, but the camp inmates could not afford much with their pocket money. There was hardly any contact with the people living in the direct neighbourhood. They had to rely on each other and integration in society was not possible. It was precisely as the Dutch government had intended.

The Central Refugee Camp Westerbork was governed by the Committee of Supervision and Relief, in which several organisations were represented, including Jewish refugee organisations and the non-Jewish welfare organisation ‘Opbouw Drenthe' [building up district Drenthe]. Chief Rabbi A.S. Levisson from Leeuwarden also was a member of this committee. He argued in favour of maintaining Jewish religious rituals in the camp. That’s why a space was arranged as a synagogue where both orthodox, as well as liberal Jews could practice their religion.

During the war, the camp remained densely populated. By the end of April 1940, 749 people stayed at the refugee camp. By now, not only young, vital and strong people – the desired category – stayed at the refugee camp, but also families with young children and elderly.

Definitielijst

- heat

- High-explosive anti-tank warhead. Shaped charge projectile to punch through armour. Used in e.g. bazooka or in the Panzerfaust.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- synagogue

- Jewish house of prayer.

Images

Jewish refugees at work in the Central Refugee Camp Westerbork. Source: USHMM.

Jewish refugees at work in the Central Refugee Camp Westerbork. Source: USHMM.Start of the war

On 10 May 1940, Hitler’s operation Fall Gelb [Case Yellow] started – the invasion of the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg. In the Central Refugee Camp Westerbork, an evacuation plan had been drawn up, which was executed immediately after the German invasion. The goal of the plan was to have the camp inmates escape to England via the province of Zeeland, but they never made it that far. They left by train in Hooghalen, but they never made it past Zwolle, because the IJssel bridge had been blown up. The train with refugees travelled towards the IJsselmeer Dam instead, but the journey ended in Leeuwarden. Initially they were received by families, but the Dutch authorities decided to send them back to Westerbork. "(…) we found ourselves where we had left, the atmosphere that was present in Germany when I fled. The fear. It was like the time I escaped illegally to the Netherlands. In fact it didn’t get you anywhere. They still managed to catch you" according to Werner Bloch, a Jewish refugee who ended up in camp Westerbork after the Crystal Night.

On 15 May, the force of arms between the German and the Dutch armies officially ended. That day, Commander-in-chief General Henri Winkelman signed the Dutch capitulation treaty in Rijsoord. Despite the fact that the management of camp Westerbork was not yet in German hands, changes were made to the camp administration. The management of the camp was taken over from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs by the Ministry of Justice. Director Syswerda was also replaced, by reserve-captain J. Schol, who previously had worked as supervisor of a refugee camp in the Hook of Holland.

Now that an army officer managed the refugee camp on behalf of the Justice Department, a much more severe policy was pursued. Up until this time, the camp inmates were allowed to access and leave the camp whenever they wanted, but now they had to officially ask permission for it. If a camp inmate stayed outside the camp for longer than a day, (s)he had to obtain a stamp from the nearest police station. It was not easy to obtain permission to leave the camp temporarily: "We hardly ever were allowed to leave the camp, while all the Dutch Jews could walk around freely in those days", said camp inmate Uri de Vries. Signs were used to indicate the boundaries of the camp site. From now on, the refugees also had to perform labour. Work was being undertaken in workshops, on the farm and in camp administration. The camp inmates were rewarded for the work with pocket money.

The surveillance of the camp was also being dealt with much more seriously. Previously, only a few constables monitored the camp, but now, a squad of fifteen military police was deployed for surveillance. Commander Schol was supported in the camp by assistant commander J.M.I.J. Haan, accountant M. Broere and thirty other employees.

Daily life in the refugee camp largely resembled military life. In the morning and evening a roll call was introduced. Guards were on patrol and regularly was checked if the beds had been made up, as was common practice in military barracks. Also other measures that were taken, limited the freedom of the camp inmates. Letter censorship was increased and sealed letters were no longer accepted by the postal department. Talking during work was prohibited. One positive outcome of the new camp policy was the fact that finally more attention was given to education.

With his tight reign, Commander Schol created the foundation for the German camp management. Similar to the Arbeitskommandos in the German concentration camps, in Westerbork so called Dienstbereiche were created. Because the camp inmates all had the German or Austrian nationality, German names were being used. Each Dienstbereich was led by a Dienstleiter and his Stellvertreter (replacement). Above the Dienstleiter was the Obergruppenleiter. These important positions were all being fulfilled by camp inmates from the very beginning.

Although the regime of commander Schol was much more severe than it was during the time that that the Ministry of the Interior managed the refugee camp, inhumane actions against camp inmates never took place. This was not to the liking of some German authorities, as is evident from a report of August 1941 to the Beauftragte of Reichskommisar Arthur Seyss Inquart in Drenthe : "I’m under the impression that the Jews here are being treated much too humane, and that, because of the attitude of the camp commander, the Jews feel very much at ease. (…) It will therefore be necessary to appoint a different camp commander."

During the severe winter of 1941-1942, the stay in Westerbork was extremely unpleasant. There was a fuel shortage and because of that, everything that could possible burn, was used to create fire. The food supply was also insufficient. As of February 1942, many building projects took place by order of the German occupiers. 24 new barracks were built which could accommodate about 250-300 people. Also some smaller buildings were put up. The building work was being performed by Dutch building contractors. They deployed the camp inmates as workmen. In July 1942, 1,100 refugees were staying in the camp. The total capacity of 1,800 residents had not yet been reached, so the extension of the camp meant that more inmates were being anticipated. The camp inmates did not know exactly why the camp was being extended. Uri de Vries: "(…) gradually an extremely large complex of barracks was being built. We should have asked ourselves why this was going on, but we didn't. I’m not sure if this was because we were naive or that I could not grasp it, because I was just a child. Anyway, we did not think about why and how the camp was being extended. But half a year later, it all became clear."

Definitielijst

- capitulation

- Agreement between fighting parties concerning the surrender of a country or an army.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

Beginning of the Persecution of the Jews

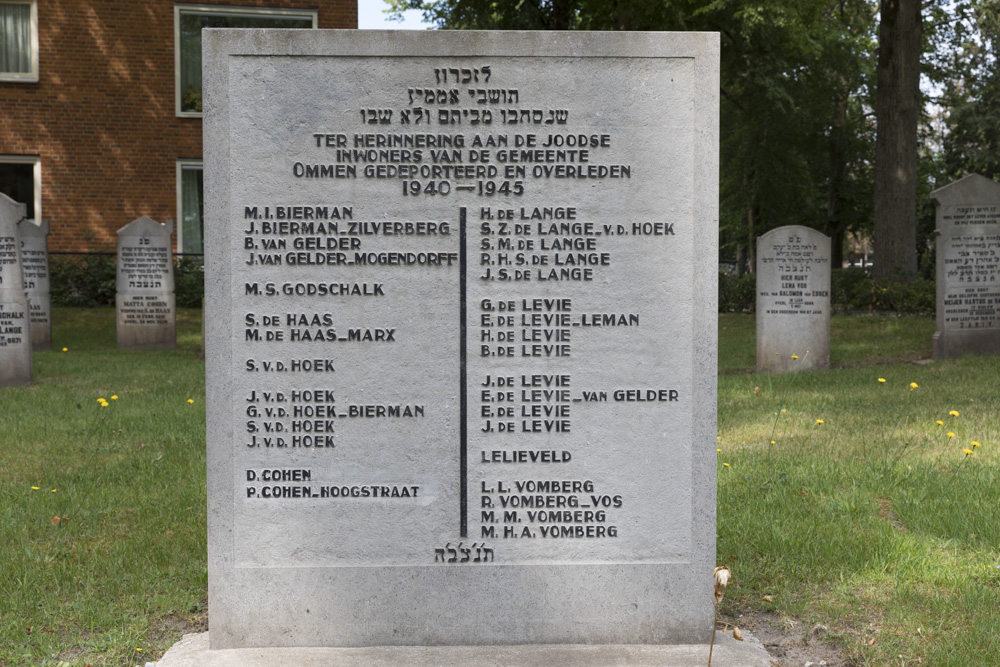

In January 1941 the German occupiers announced that all the Jews in the Netherlands had to register themselves. At that time, 160,000 Jews, according to the Nazi definitions, lived in the Netherlands, 137,000 of them had the Dutch nationality. Eventually 157,000 Jews were registered at the Zentralstelle für jüdische Auswanderung, the central agency for Jewish immigration in Amsterdam, including ‘quarter and half Jews’, the Jews with respectively one or two Jewish grandparents. What they did not realise, was the fact that by registering themselves, they signed their own death sentence. These data would ultimately be used to summon them for departure to transit camp Westerbork and the extermination camps that would follow.

Before the Jews had to register themselves in 1941, the German occupiers had relatively left them alone. Generalkommissar für Verwaltung und Justiz (management and justice) Dr. Friederich Wimmer had even declared to the Dutch secretary-general of the Interior, Karel Johannes Frederiks, that according to German authorities ‘the Jewish problem’ did not exist. In the first few weeks of the occupation, the Jews only had to endure the badger and provocation of NSB-ers [members of the Dutch national socialist movement]. Soon, Wimmer failed to keep his promise: several measures were taken to socially isolate the Jews. The first anti-Jewish measure was that as of 1 July 1940, Jews were no longer allowed to take advantage of air-raid protection. A second measure was taken on 31 July 1940: as of 5 August ritual slaughtering of cattle was prohibited. After already some measures had been taken to prevent Jews from being hired by government agencies, all civil servants had to sign a declaration of Aryan origin on 5 October 1940. Later on 21 November, all Jews were fired from civil service, because obviously they weren’t eligible for the declaration of Aryan origin. From now on, Jews were not able to work at schools, ministries, local government offices and universities.

In 1941 the anti-Jewish policy in the Netherlands was further accentuated. Because of the measures being taken, the Jews got excluded even more. As of 7 January 1941 they were not allowed to visit cinemas, and from 31 May they weren’t allowed to visit swimming pools and public parks and as of 1 September Jewish children had to go to separate schools. Since everywhere signs would appear with "Prohibited for Jews", the Jews had to rely more and more on each other. In Amsterdam the Jewish neighbourhood was closed off. In this neighbourhood Jews from Amsterdam and the surrounding areas were being concentrated in the period 1941-1943. On 13 February 1941, the Jewish Council was founded in Amsterdam. This organisation was led by David Cohen and Abraham Asscher and represented the Jewish community. The Jewish Council was exploited by the Germans to coordinate the persecution and eventually the extermination of their companions in misfortune.

Although the Jews were still under the impression that their registration with the Zentralstelle für jüdische Auswanderung was meant to ease their immigration to countries outside Europe, the Nazis by now had learned that the ‘Jewish problem’ could not be solved by immigration, because of the war and the refusal by other countries to allow Jews to enter their countries. On 20 January 1942 the Wannsee Conference took place. Since operation Barbarossa, the Jews were being exterminated in the Soviet Union by Einsatzgruppen. It was decided that all European Jews had to be killed. In order to realize the total extermination of Jews, extermination camps were being built in Poland. Here the Jews could be systematically killed in gas chambers. During the Wannsee Conference the practical realization of the Endlösung der Judenfrage – the final solution of the Jew problem – was discussed. In the minutes of the Wannsee Conference the number of 160,000 Jews in the Netherlands was mentioned. The goal was to kill them all.

Definitielijst

- Endlösung

- Euphemistic term for the final solution the Nazis had in store for the “Jewish problem”. Eventually the Endlösung would get the form of annihilating the entire Jewish people in extermination camps.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- NSB

- National Socialist Movement. Dutch political party sympathising with the Nazis.

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- Wannsee Conference

- Conference at the Wannsee on 20 January 1942. The Nazi’s made final agreements about the extermination of Jews in Europe, the Final Solution (Ëndlösung).

Images

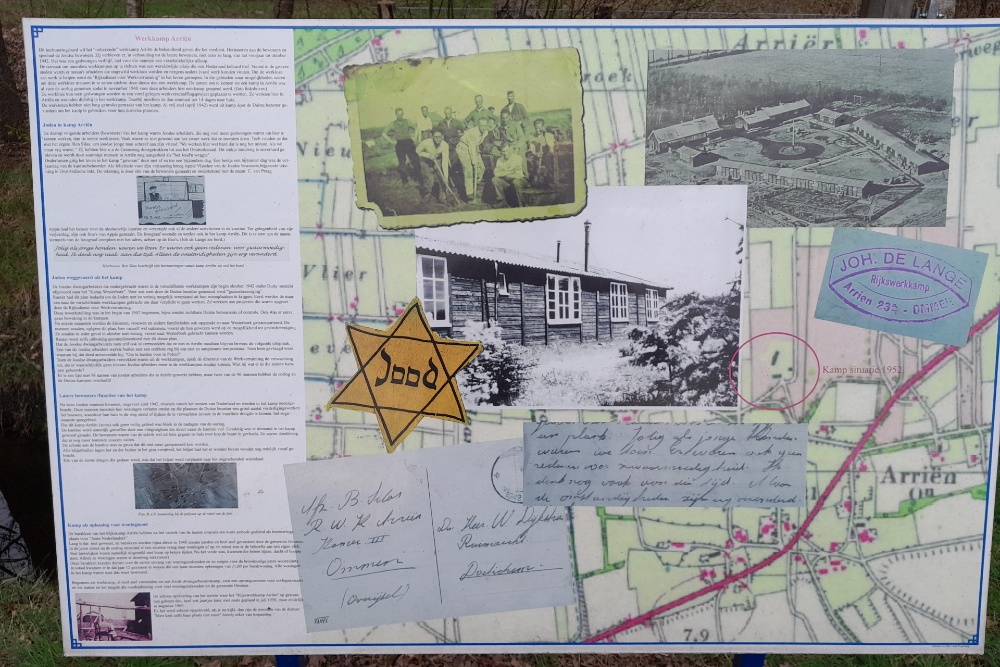

Take-over by the SS

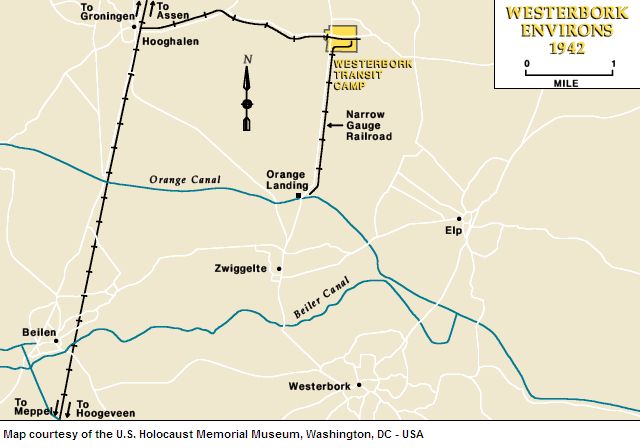

In the summer of 1941, before the Wannsee Conference took place, they had secretly decided to Entjüdung [elimination of all Jewish influence] in the Netherlands. All Jewish Dutch residents would be sent to work camps in Poland and Germany via camp Westerbork functioning as central transit camp. In reality the majority of the Jews did not end up in work camps, but in the extermination camps Sobibor and Auschwitz-Birkenau. To execute the elimination of all Jewish influence in the Netherlands as efficiently as possible, the management by the Dutch Ministry of Justice of the Central Refugee Camp Westerbork was taken over by Schutzstaffel (SS) – the comprehensive National Socialistic organisation responsible for the execution of the Final Solution on 1 July 1942. Within the extensive organisational structure of the SS, the Befehlshaber der Sicherheitspolizei und der SD (BdS) was responsible for the camp in Westerbork. This position was held by, respectively SS-Gruppenführer Dr. Wilhelm Harster (15 July 1940 - 29 August 1943), SS-Gruppenführer Erich Naumann (September 1943 - July 1944) and SS-Oberführer Karl Eberhard Schöngarth (as of September 1944). The BdS in the Netherlands had its seat in The Hague and had to report to Generalkommissar für das Sicherheitswesen Höhere SS und Polizeiführer Hanns Rauter.

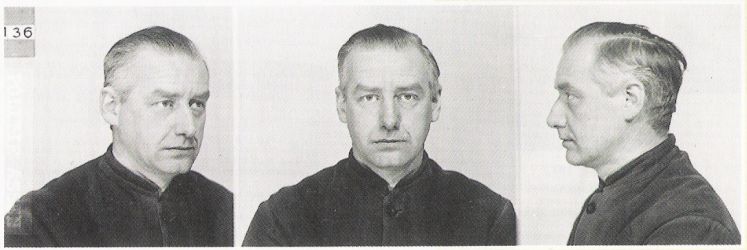

Now that the camp was no longer used as refugee camp, but instead functioned as transit camp, it received a different name. Up until one day before the liberation of the camp in April 1945, it was officially known as Polizeiliches Judendurchgangslager Westerbork. Commander Schol continued to work in Westerbork until December 1942, but he hardly had any influence since the SS took over command and a German commander had been appointed. The first German camp commander in Westerbork was SS-Sturmbannführer Dr. Erich Deppner. In the book "De Ondergang" [Extinction. The Persecution and Destruction of Dutch Jewry, 1940–1945] he was described by Jacques Presser as "a typical SS-leader, cold as ice, ruthless, a killer with an officer’s personality." Deppner was succeeded by SS-Obersturmführer Josef Hugo Dischner in September 1942. Presser described him as "a rough, brainless SS-man, almost always under the influence of alcohol." Dischner was also replaced shortly by inspector Bohrmann, "absolutely useless", according to Presser. His appointment was also temporarily, because SS-Obersturmführer Albert Gemmeker took over command on 12 October 1942. He remained camp commander until the shutdown of the camp in 1945.

Contrary to his predecessors, this camp commander had the ambition to organize the camp management as tight and efficiently as possible. Albert Gemmeker did not have a reputation as a typical brute Nazi and was even referred to as a ‘gentleman-commander’. In his book, Presser described that certain inmates found him to be "difficult to read", and "from appearance absolutely proper, not a ‘Kraut’, but more of an English sportsman, ‘very gifted, but extremely dangerous’. He never lost his temper or shouted. According to himself he ‘treated the Jews in the best possible manner as far as was possible under the Nazi regime.’

Although Gemmeker was married, he had an affair with Miss Elisabeth Helena Hassel-Mullender, a secretary at camp Westerbork. Contrary to Gemmeker his mistress was harsh and ruthless. She scolded inmates, but didn’t abuse them because Gemmeker had strictly forbidden this. If the face or the behaviour of an inmate was not to her liking, she would have the inmate be locked up in the punishment cell. Several inmates were put on transport by her as punishment. Because of her brutal behaviour she was known among the camp inmates as ‘the evil I of Gemmeker’ and was even called ‘an evil spirit’ or ‘she-devil’. She was hated, even by the inmates who fulfilled an important position within the Jewish self-government in the camp.Not only camp management, but also the guards changed after the take-over by the SS. The camp site was fenced off with barbed wire and seven watch towers were built. The SS-Wachbataillon was charged with the outside surveillance, while Dutch military police was responsible for maintaining order within the camp. The military police, accompanied by Dutch policemen were also in charge of arranging the arrival and departure of prisoners from Hooghalen train station. Escorting prisoners from and to Hooghalen station came to an end when the camp got its own railway connection. Eventually the military police also took over the outside surveillance from the SS.

Definitielijst

- Auschwitz-Birkenau

- The largest German concentration camp, located in Poland. Liberated on 26 January 1945. An estimated 1,1 million people, mainly Jews, perished here mainly in the gas chambers.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Wannsee Conference

- Conference at the Wannsee on 20 January 1942. The Nazi’s made final agreements about the extermination of Jews in Europe, the Final Solution (Ëndlösung).

Images

Camp commander Gemmeker and Frau Hassel. Source: J. Presser, Ondergang.

Camp commander Gemmeker and Frau Hassel. Source: J. Presser, Ondergang. Surroundings of transit camp Westerbork in 1942. Source: USHMM.

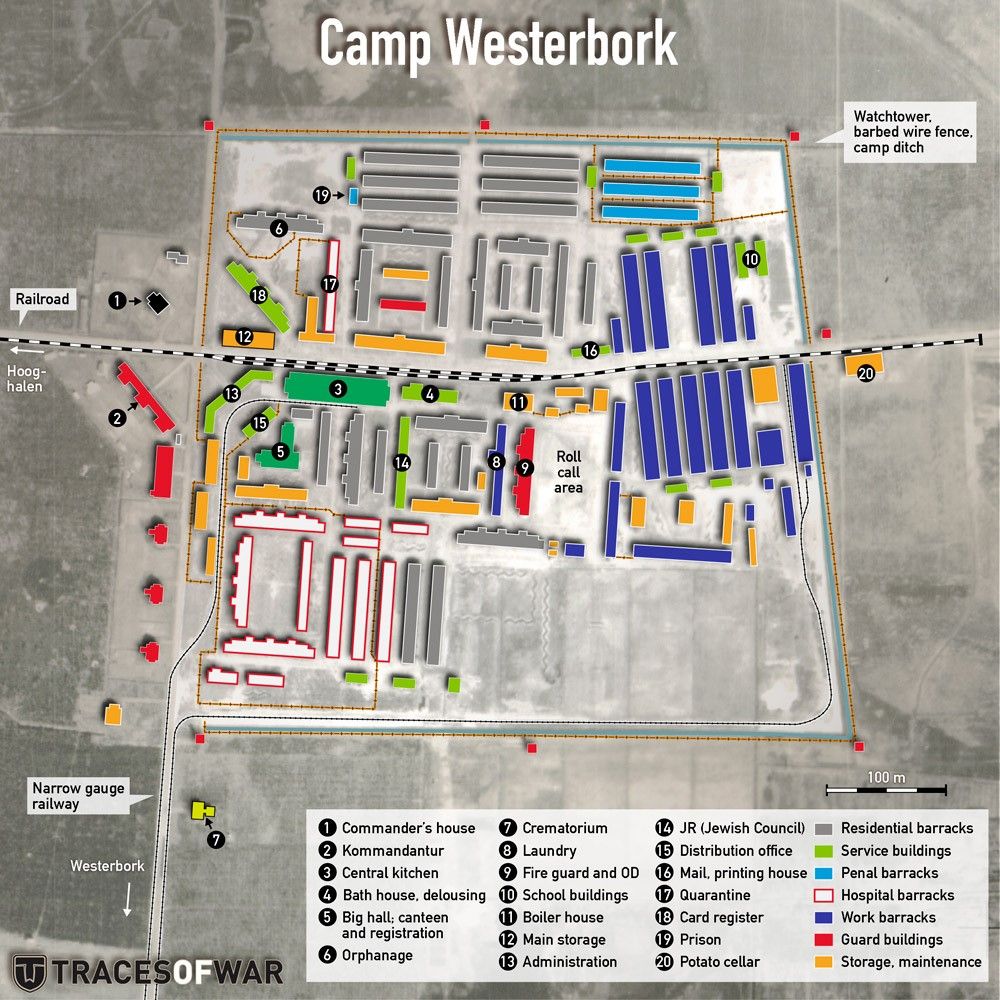

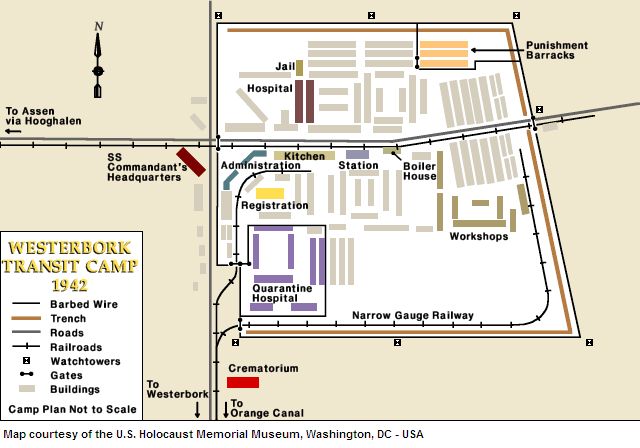

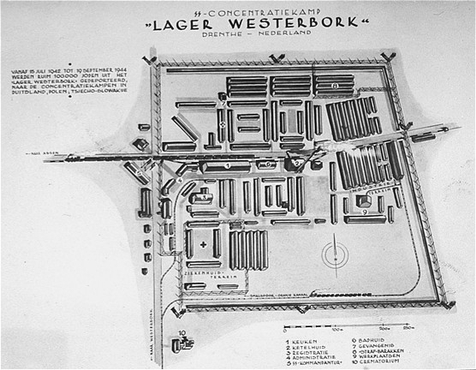

Surroundings of transit camp Westerbork in 1942. Source: USHMM. Map of of transit camp Westerbork in 1942. Source: USHMM.

Map of of transit camp Westerbork in 1942. Source: USHMM.The Final Solution

While camp Westerbork was prepared to function as transit camp for the Jews and gipsies who had to be deported to the East, several measures were taken in 1942 to facilitate the Entjüdung of the Netherlands. To make Jews more recognisable, a ‘J’ was stamped in their identity card as of 23 January 1942. A couple of months later, on 2 May, they were forced to wear a Star of David. Now that the process of registering was completed, the Jews were easily recognisable and the gathering of Jews in Amsterdam had been on the way, everything was in order for the next step: deportation.

On 26 June, the Jewish Council was informed of the deportation. On 4 July, the first notices for labour deployment in Germany were sent out. In the night of 14-15 July, the first two trains with Jews left from Amsterdam towards camp Westerbork. In advance, a raid took place to exert pressure. 700 Jews were rounded up and would be transported to concentration camp Mauthausen if the notices were massively ignored. Despite this threat, one-third of the summoned Jews didn’t turn up at Amsterdam station. This was a set-back for the Germans. They therefore organized a second raid in Amsterdam on 6 August. 1,600 people were arrested, of which 700 were transported to Westerbork.

At various locations in the Netherlands, raids and transports to Westerbork took place in 1942 and 1943. The Jewish Council was mobilized by the Nazis to organise these transports. Their influence on the deportation policy was little, but they did have a say in the composition of the list of persons to be transported. The Jewish Council provided prominent Jews and their families with a much desired (temporary) exemption (so-called Sperre) from transportation. But eventually even the Jews with such an exemption would end up in camp Westerbork.

Definitielijst

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Mauthausen

- Place in Austria where the Nazi’s established a concentration camp from 1938 to 1945.

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

Images

Dutch Jews on the way to camp Westerbork in October 1942. Source: USHMM.

Dutch Jews on the way to camp Westerbork in October 1942. Source: USHMM.Living conditions

The arrival in camp Westerbork was a strange experience for the Jews that arrived here. Not long ago they lived their lives in freedom, but now they didn’t know what to expect from the future. Louis de Wijze tells about his arrival in camp Westerbork: "And then you arrive at the camp. You lived a comfortable life. (…) And then you end up at some train station in the middle of nowhere. There are all these people, hundreds, thousands of people on a desolate small station. (…) You can see that all the people are looking confused. What’s happening?" This desperation is not strange, because many prisoners in Westerbork indeed didn’t know what was awaiting them. Illegal press and foreign broadcasting stations did report sinister news about the extermination of Jews, but many of them didn’t want to or couldn’t picture this at this point of time. Jules Schelvis, a Dutch Jew that had been transported to Westerbork, explains it as follows: "We were afraid of the unknown. We thought that we just had to work in factories, in the war industry, in road construction, the mining industry, etc. We didn’t want to think about what the people who were ill or who were weak had to do in the East. We thought: who knows, maybe they have to peel potatoes and work in the kitchen."

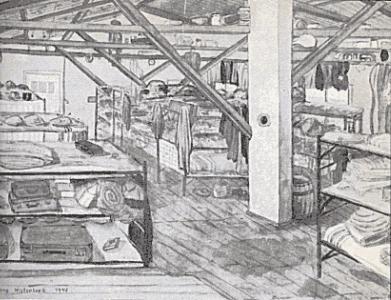

After their arrival in camp Westerbork, camp live started in anticipation of the deportation to the ‘work camps’. This camp life resembled that of other concentration camps. There was hardly any space and no privacy in the barracks. Despite the fact that the camp had meanwhile been extended to 107 barracks, each of which could accommodate 300 persons, many of them soon became overcrowded. This caused the hygienic conditions to worsen and the food supply was no longer sufficient.

Discipline in the camp was strict: you were transferred to the punishment barracks for even the smallest offence. Here you had to perform hard labour, and much worse, there was a greater chance of being deported. Prisoners who violated camp rules could also be transferred to the punishment block. Male ‘offenders’ were shaved bold and had to wear recognisable clothing. Also Jews who went underground somewhere in the Netherlands, but were caught, ended up in the punishment block. One of the rules was that prisoners could not leave there barracks after curfew. Another similarity between camp Westerbork and other concentration camps was the strict censorship applicable to letters and postcards that were sent by the prisoners.

Despite the many similarities with the living conditions in other concentration camps, there were also some striking differences with camp Westerbork. The German camp management wanted to prevent that the prisoners in Westerbork could suspect their approaching fate. Daily life in the transit camp was therefore as normal as possible and the prisoners had to be distracted in all kinds of ways. So training courses were given, they could take part in sports activities and the prisoners were given the opportunity to organise cabaret shows and music performances. They could even shop in Westerbork, in the Lagerwarenhaus (LaWa). Here small household items could be bought, such as cosmetics, toys and sometimes even flowers. The items had to be paid with special Westerbork-money. Not only could it be spent in the Lagerwarenhaus, but also at the Lagerkantine. Here fish, pickles, custard powder and lemonade could be bought. In an exchange office the prisoners could change their ‘ordinary’ money into special notes of the camp. ‘Ordinary’ money was prohibited in the camp, and the possibility to change common currency gave the Nazis the easy opportunity to confiscate this money.

The children in camp Westerbork were also treated well. For them, not much changed, because just like at home, they had to go to school every day. The smallest children were taken care of in a day nursery. Children that were a bit older went to kindergarten and for the older children there was compulsory education from the age of 6 to 14 years. There was a special orphan home for orphans with a well-equipped ward for babies and toddlers. Although some children would only be alive for a couple of days, at the end of the school year they would receive a school report, drawn up in German. The children could not escape the deportations and the same fate awaited their supervisors and teachers. Classes would therefore fall out sometimes, because it would take some time before substitute teachers were found.

Besides childcare and education, the medical care was also good at Westerbork. A medical team could easily be put together, because many Jews were surgeon, doctor or dentist. A job in the medical care was much sought after, because it provided Sperre. At a certain point in time, the hospital in camp Westerbork had 1,725 beds, 120 doctors and 1,000 employees. When camp Westerbork was overcrowded, the medical care also was no longer sufficient, as is evident from the story of Westerbork prisoner Bob Cohen: "Our new hospital became overcrowded and was therefore extended with new barracks – five wards. (…) A day later already full again. A new barrack was fitted out as emergency hospital. People were stacked 3-high on top of each other. (…) More and more patients were added. Three hundred found shelter, but this barrack too became overcrowded. The remainder of the patients had to stay put. As far as the nursing was concerned: all material such as chamber pots and urinals were lacking, there were no plates to eat from and there was no hot water. There were also no sheets and blankets. Soon the first death occurred, followed soon by more deaths."

751 people died in camp Westerbork. Compared to the concentration camps in Germany and Poland this number is very low. This was a direct result of the ‘humane’ policy that was pursued in the camp. But this low mortality rate is also due to the relatively short period of time that most prisoners would stay in Westerbork.

Definitielijst

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

Images

Map of transit camp Westerbork. Source: USHMM.

Map of transit camp Westerbork. Source: USHMM. Daily life in the camp. Source: J. Presser, Ondergang.

Daily life in the camp. Source: J. Presser, Ondergang. Part of a living barrack. Source: J. Presser, Ondergang.

Part of a living barrack. Source: J. Presser, Ondergang. Barrack for sick children with wall drawings including The Pied Piper of Hamelin. Source: J. Presser, Ondergang.

Barrack for sick children with wall drawings including The Pied Piper of Hamelin. Source: J. Presser, Ondergang. Children at a school barrack. Source: J. Presser, Ondergang.

Children at a school barrack. Source: J. Presser, Ondergang.Prisoners and camp management

In camp Westerbork the prisoners were responsible for camp management to a great extent. For the Nazis it was very common to deploy Jews for the organisation of the Final Solution, so camp Westerbork was no exception. The Jewish Councils that were founded in various countries are a good example of this, as were the Sonderkommandos in the extermination camps that were responsible for clearing out the gas chambers and burning the bodies of their fellow prisoners.

The Jewish management in camp Westerbork was largely made up of alte Lagerinsassen, a group of about 1,200 Jews that had already been staying in camp Westerbork before the SS took over the power. This group was made up of German and Austrian refugees. Because they spoke German, they were treated special and received the best jobs. Because of this privileged position, fellow prisoners gave them the nickname ‘the aristocracy of Westerbork’. Head of the Jewish Council was Kurt Schlesinger. He was referred to as the ‘Mayor of Westerbork’. Camp commander Albert Gemmeker was highly content with the way Schlesinger executed the directions given by Gemmeker.

At first, the camp organisation remained the same as it was under command of camp commander Schol, but eventually it was not made up of twelve Dienstbereiche [service divisions] anymore, but six. A job within one of the departments of the Groups, was much sought after, because this meant a temporary exemption of transportation. No matter how hard the work was or how many hours had to be worked, having a job meant having a little bit of security. Especially for prisoners at higher positions within camp management, including the Dienstleiter [managers] the chance of being deported was much smaller, because they were listed on the Stammliste, a list with persons who were deemed indispensable within camp management. Having a job in camp Westerbork not only entailed a temporary exemption of transportation. It was also a much more pleasurable way of getting through the day. Working in the camp offered a change of scene.

Many prisoners were able to obtain a job within Dienstbereich XI, the industry. Despite the fact that this service division was considered as ‘Wirtschaftswichtig’ – important to the economy –camp Westerbork never played an important economic role. ‘Economically important’ work that was being undertaken in Westerbork, included scraping off silver foil from objects to which it was stuck and destroying batteries. Prisoners with external duties were charged with agricultural work in the countryside, such as making hay and lifting potatoes. After the Dienstbereiche were restricted to six, several production units remained. Dienstbereich VI for example, was busy with Zerlegungsbetriebe: demolition work, such as dismantling parts from crashed aircraft.

One of the Dienstbereiche was the Ordnungsdienst (OD) [police force]. Because the members of the OD worked closely together with the SS, they were not well-liked by their fellow prisoners. That’s why they were called ‘the Jewish SS’. The OD was among other things responsible for maintaining order in the camp, reporting offences to the camp management, preventing escape attempts from taking place and escorting prisoners who were being deported. The OD was set up because the number of Dutch military police was too small to keep the order in the camp. The core of the OD was made up of members of the fire department that was established when the camp was still a refugee camp. After the take-over by the SS, especially former military were eligible to perform this humiliating job. The OD was at its strongest in April 1943, with 182 men. The OD was led by the Austrian Jew Arthur Pisk.

The OD was also responsible for guarding the prisoners in the punishment barrack and supervised the punishment block that had to perform hard labour outside the camp. Escapes seldom took place, because inmates were afraid of the retaliation measures that would be taken by the SS, and which would affect family members or fellow inmates. In March 1944, someone from the farm group escaped, a work group under command of the Austrian Jew Bauer. The whole group was deported as reprisal. In general, not many prisoners wanted to be responsible for their family members or fellow inmates being deported. Besides that, escaped Jews could not easily find refuge in the occupied Netherlands, and the chance that they would be picked up again by police was extremely large. Nevertheless, about two hundred inmates escaped from camp Westerbork.

The OD was also put into action on several occasions outside the camp. For instance, OD members were involved in the evacuation of the Jewish psychiatric institution ‘Het Apeldoornsche Bosch’ in Apeldoorn on 21 January 1943. That same year, they were also deployed during some large raids in Amsterdam. According to former prisoner Louis de Wijze that must have been "a bitter experience for Jews from Amsterdam. One must not forget that people were being collected by their own people, so for people to have to deal with that takes a lot. But one has to remember that those people didn’t have a choice. If they would refuse, they would be deported themselves. So that was a huge inner struggle. It was perhaps one of the most gruesome cruelties committed by the SS-ers."

Definitielijst

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

Images

Members of the OD coordinate the arrival of Jews in camp Westerbork. Source: www.ushmm.org/.

Members of the OD coordinate the arrival of Jews in camp Westerbork. Source: www.ushmm.org/.Sports and entertainment

Camp commander Albert Gemmeker found it important that prisoners in Westerbork could relax by doing sports or could enjoy music and cabaret. It’s not difficult to explain why he was such an advocate of this. Prisoners who were kept busy were much too distracted to be aware of the fate that awaited them. The opportunity to relax was therefore also used to disguise the fact that prisoners would become aware that they eventually would be killed.

Sports that were being practised by prisoners in camp Westerbork included soccer and boxing. The soccer team of camp Westerbork was led by an Austrian former international soccer player. Every Sunday afternoon there was a great public interest for the soccer matches that were being played at the site where also the roll calls took place. Boxing matches were held in the Great Hall. They were professionally organised and included referees, assistants and ring doctors. Former Dutch boxing champion Bert Bril, who had refused to take part in the Olympic Games in Germany in 1936, was also involved in the organisation of the boxing matches in Westerbork. Other popular sports in camp Westerbork included handball, athletics and playing chess.

Even before the camp was taken over by the SS, a camp orchestra was formed, called the Gruppe Musik Lager Westerbork [music group camp Westerbork]. The work of Jewish composers was regarded as Entartete Musik [corrupt music] in Nazi Germany and in the territories occupied by the Germans. It was strictly forbidden to listen to this music, let alone making this music. Gemmeker, however, disregarded this ban. The repertory of the camp orchestra in Westerbork exclusively included the works of Jewish composers. Mainly light music was played, because Gemmeker was of the opinion that this type of music could best chase away one’s cares. The classically trained musicians gladly adopted his wishes, because being a member of the orchestra entailed a temporary exemption from deportation.

In the spring of 1943, Gemmeker gave three well-known Jewish artists Max Ehrlich, Willy Rosen and Erich Ziegler, all refugees from Germany, the order to establish a cabaret company. He enjoyed the first performance of the Gruppe Bühne Westerbork [performance group Westerbork] so much that from then on, he gave the cabaret performers the freedom to organise their performances how they wanted it. Much was invested in materials and costumes to make a professional impression. Thanks to these efforts and the collaboration of many successful Jewish artists, the cabaret company in Westerbork was probably one of the best in the Netherlands at that time.

Every Tuesday, the day on which also the deportations took place, the Bunter Abend [variety show] was organised in the Great Hall. Performances took place on a stage that was made of wood from the destroyed synagogue in Assen. Camp commander Gemmeker was always seated on the first row and visibly enjoyed all performances. But he refused to applaud the Jewish artists, because as an Aryan this was not something he could do. However, it was obvious that he enjoyed the shows, because he would give the cabaret performers, musicians, singers and dancers a temporary exemption from deportation.

Camp commander Gemmeker especially liked the German repertoire. But Gemmeker did not appreciate the songs from the Dutch artists Max Kannewasser and Nol van Wezel, known as ‘Johnny and Jones’ with their songs with a somewhat quasi-English intonation. That’s why the couple only performed once on the stage during the variety show. They did however perform in the Lagercafé [camp pub]. Especially their Westerbork-serenade, about being in love in camp Westerbork, was extremely popular.

On 4 September 1944, ‘Johnny and Jones’ were deported to Theresienstadt. In the spring of 1945 they died shortly one after the other in concentration camp Bergen-Belsen. Many other artists underwent the same fate. The last performance in camp Westerbork took place in July 1944. Nazi command in The Hague had demonstrated against the exuberant cultural activities in camp Westerbork. They could not stand the fact that Jews were allowed to have so much fun, while the German population had to give up all luxury due of the war. On 3 August 1944 the discontinuation of the cabaret and orchestra company was announced. The exemptions from deportations that the artists had, were being revoked and in September they were all deported to Theresienstadt. Despite the fact that Theresienstadt was in fact a camp for privileged Jews, many of the artists did not survive the war.

Definitielijst

- collaboration

- Cooperation of the people with the occupying forces, more generally spoken the term for individuals who cooperate with the occupying force is collaborator.

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- synagogue

- Jewish house of prayer.

- Theresienstadt

- City in the Czech Republic. Here the Nazis established a model concentration camp.

Images

The camp orchestra. Source: J. Presser, Ondergang.

The camp orchestra. Source: J. Presser, Ondergang. The successful duo Johnny & Jones. Source: Joods Historisch Museum.

The successful duo Johnny & Jones. Source: Joods Historisch Museum.Deportations and extermination

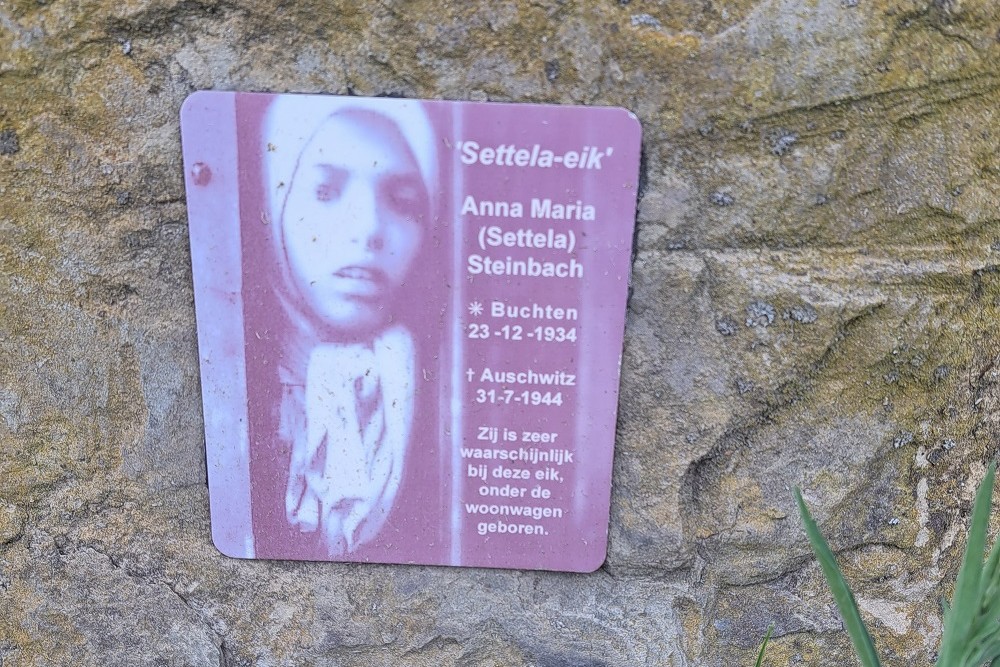

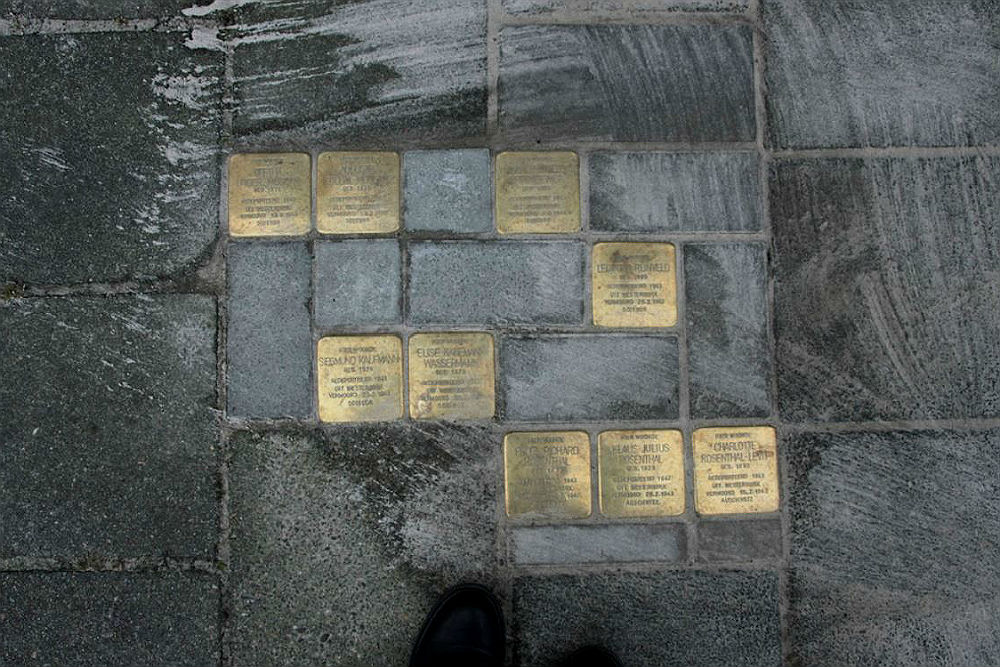

Although there were several ways of obtaining an exemption from deportation, eventually nobody could escape the deportations to the east. In total 93 transports took place from camp Westerbork. Also a number of smaller transports with only a few dozen of people took place. Of the approximately 107,000 Jews transported from the Netherlands, 101,525 of them (41,156 men, 45,867 women and 14,502 children) were temporarily incarcerated in Westerbork. Also 245 Sinti and dozens of resistance fighters stayed in the transit camp for a certain period. More than 95% of the people deported from Westerbork were murdered by the Nazis.

The first 32 deportations from Westerbork took place in July 1942. The transports left from the station in Hooghalen, but as of 2 November 1942, the trains took off from the camp itself. The railroad in the camp ran parallel to the main road, called the ‘Boulevard des Misères’ by the prisoners. Other names included ‘Rachmones Allee’ or ‘Tsorres Allee’, that is ‘street of misery’ and ‘street of troubles’. During the first few months, the trains left without a regular schedule to the concentration and extermination camps. But as of February 1943, Tuesday was the fixed day of transportation. The number of Jews that had to be deported was determined by de department IV B4 of the RSHA, under command of Adolf Eichmann. The numbers were being passed on to the national department of the Sicherheitspolizei [security policy] and the SD in The Hague. Here, SS-Sturmbannführer Zöpf was responsible for passing on the orders to camp commander Albert Gemmeker. Although Gemmeker in fact had to decide who would be deported, he left this job over to Schlesinger and his staff. Jacques Presser described this decision-making process in "De Ondergang" as follows: "How many and when Jews had to be deported was decided upon by the Germans, but Gemmeker determined which persons had to be deported. But actually deciding who did or didn’t have to go, that was left by Gemmeker to his paladins."

The entire camp was in suspense when the names of those being deported were being read out. "I anxiously awaited the moment that the names starting with an ‘S’ came round on the list", told former prisoner Jules Schelvis, "After a while I heard: Schelvis Jules, Schelvis-Borzykowski Rachel, Stodel Abraham, Stodel-Borzykowski Hella. After Hella’s name had been read out, we held each others hands. All of a sudden a rush of acceptance came over us, because it was now final that we were all staying together. That’s what we wanted. Now, the moment had come that we were all leaving to the south together. We could all support each other. Luckily we were healthy and sturdy." Another former prisoner explained that after the reading out of the names "indescribable scenes" took place. "The piercing cries of a terrified, slightly mentally ill mother, children crying, the dazed faces of men, insane cries of those that stayed behind. All that made me shiver."

Yet another former prisoner said that "The people that had to go, went about packing their bags or dressing up their children. Those that did not have to leave, often cried of relief or danced or went wild with joy." Then the prisoners were escorted by the officials responsible for order and the Fliegende Kolonne – a Jewish support group responsible for escorting arriving and leaving transports – to the train station where the train already stood waiting. Most transports were carried out with goods waggons, but passenger waggons were also deployed for transport to Bergen-Belsen and Theresienstadt. On the loading platform "one handcart stood still, on it were two small barrels", as Jules Schelvis remembered. "One of them was filled with drinking water, the other one was empty. It was meant for answering nature’s call. Even a child could see that just one barrel for that purpose for so many people was insufficient. (…) There was no comfort whatsoever in the waggons. No provisions were made for people that had to travel so far. There was no straw on the floor, there were no decent mattresses, no hooks to hang anything on it, no nothing. We were being treated less than animals, because for animals there would at least be rings in the walls. Those rings had been removed."

The journey would begin when all the waggons had been filled. Depending on the destination, the journey would take several days and nights. The Dutch rail company (NS) took care of the train transport up until Nieuweschans at the German-Dutch border. Here the transport was taken over by the Deutsche Reichsbahn [the German rail company]. Transport conditions worsened after a while, because of the ever increasing chaos on the railways. On some occasions, due to allied bombings, trains would stand still for longer periods of times, sometimes even weeks. Lex van Weren remembers that his transport came to a ten-hour standstill following a bombardment in Dresden. "That was a tough situation. In the goods waggon you could only try to kneel down or you had to lay all over each other. It was important that we kept telling each other stories. And we said to one another: "It’s okay, the war will only last another week or three."

In addition to a lack of comfort and hygiene, there was hardly any drinking water or food for the Jews in the goods waggons. Due to the terrible conditions, several people died before reaching the final destination. There was practically no chance of escaping, because the waggons were closed off and the small windows were barred. Moreover, the transports were guarded by the police. From the outside, for instance the resistance, no attempts were made to sabotage the transports from the Netherlands. Nor did the Allies try to bomb the railway lines in order to bring the transports to a standstill. The trains "rollten, dass man sagen kann, es war eine Pracht" [the trains kept rolling, and what a beautiful sight it was indeed], according to transport coordinator Adolf Eichmann.

Where were the transports heading? Although the transport conditions were pretty bad, many Jews could still not imagine that they were underway to a place where they would be exterminated, as is evident from the words of Jules Schelvis: "I myself thought as well: I’m only twenty-three, young and healthy. I’ll probably have to work, but that’s fine. (…) What can happen to me? Every time that special Jewish mentality would come up: you pick yourself up after every setback. One could not imagine that all Jews had to be exterminated. They told me when I arrived at Auschwitz and still I didn’t want to believe it. I saw the smoke coming from the crematoria and still I didn’t want to believe it. It went beyond my comprehension."

No matter how optimistic prisoners like Jules Schelvis were: unfortunately, what they didn’t want to think about and what they could not imagine, proved to be true. Their final destination often would mean their death. The overview below was extracted from page 23 from the book "Kamp Westerbork" by Dirk Mulder.

| Deported from Westerbork to: | Survivors: | |

| Auschwitz | 58,380 | 854 |

| Sobibor | 34,313 | 18 |

| Theresiënstadt | 4,894 | +/- 1,980 |

| Bergen-Belsen | 3,751 | +/- 2,050 |

| Buchenwald and Ravensbrück | 150 | < 10 |

Most transports, 68 in total, left for concentration and extermination camp Auschwitz. From July 1942 to February 1943, this camp in Poland was the only final destination from the transports from camp Westerbork. During this period, 52 transports arrived here from Westerbork. Most deportees, about 72%, were killed immediately in the gas chambers of Auschwitz-Birkenau upon arrival. Others had to perform labour first, but many did not survive the inhumane working conditions. In the time between August and September 1944, yet another 16 trains from Westerbork arrived at Auschwitz. Around 50% of the arrived Jews were immediately gassed upon arrival. From the remaining 50%, a considerable number died afterwards.

The survival probability rate in extermination camp Sobibor in Poland was even smaller than the survival probability in Auschwitz. From March to July 1943, a total of 19 trains left from Westerbork towards this extermination camp. Contrary to Auschwitz, in Sobibor almost all deportees were gassed immediately upon arrival, because the camp in Sobibor was organized specifically to exterminate Jews, but Auschwitz was partly set up as a concentration and work camp.

Although the camps Theresienstadt in the Czech Republic and Bergen-Belsen in Germany were not equipped as extermination camps, the survival probability was not high during the last months of the war. The living conditions had deteriorated enormously and in Bergen-Belsen raged an obstinate typhoid epidemic. As of January 1944 deportations to these camps took place from Westerbork. It predominantly concerned prominent and privileged Jews that were deported to Theresienstadt. Jews with a visa for Palestine, a so-called Palestine pass, were deported to Bergen-Belsen. Here the survival probability was the highest.

The last transport from Westerbork left on 13 September 1944 to Bergen-Belsen. During the period of July 1942 to September 1944, camp Westerbork had played an important role in the extermination of the Dutch Jews. Besides the 93 transports from Westerbork, there were also some transports from camp Vught and possibly also some smaller transports from The Hague. The transport from Apeldoornsche Bosch left directly to Auschwitz. From the approximately 107,000 Jews that were deported from the Netherlands, only 5,450 survived the Holocaust.

Definitielijst

- Auschwitz-Birkenau

- The largest German concentration camp, located in Poland. Liberated on 26 January 1945. An estimated 1,1 million people, mainly Jews, perished here mainly in the gas chambers.

- Holocaust

- Term for the destruction of European Jewry by the Nazis. Holokauston is the Greek term for a completely burnt sacrifice.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- RSHA

- Reichssicherheitshauptamt. The central information and security service of the Third Reich.

- Theresienstadt

- City in the Czech Republic. Here the Nazis established a model concentration camp.

Images

The Boulevard des Misères. Source: J. Presser, Ondergang.

The Boulevard des Misères. Source: J. Presser, Ondergang. Members of the Ordnungsdienst help prisoners stepping in the cargo carriages. Source: USHMM.

Members of the Ordnungsdienst help prisoners stepping in the cargo carriages. Source: USHMM. On the loading platform of the transit camp. Source: USHMM.

On the loading platform of the transit camp. Source: USHMM. Even the elderly and sick were deported. On this photo yhe members of the Ordnungsdienst carry an elderly woman. Source: USHMM.

Even the elderly and sick were deported. On this photo yhe members of the Ordnungsdienst carry an elderly woman. Source: USHMM.Liberation

After the last transport from camp Westerbork in September 1944, some hundred Jews remained in the camp, including camp management. In the last months before the liberation of the camp, dozens of Jews, most probably arrested persons in hiding were imprisoned in the camp.

Because the Allies advanced further and approached Westerbork, camp commander Albert Gemmeker left the camp on 11 April 1945. He put Kurt Schlesinger in command, which in turn left command to Aad van As, a Dutch citizen who worked at the camp as Head of distribution. Now that the camp was no longer under command of the SS and German management, the camp was given a different purpose. In his last announcement on 12 April 1945, Schlesinger announced that the camp from that moment on fell under the protection of the International Red Cross and would become a Austausch – Internierungslager [exchange / prisoner camp]. The prisoners in camp Westerbork, however, were not able to become Austauschjuden (Jews that were exchanged/traded by the Nazis for Germans held in captivity), because the liberation of the camp would take place just one day later. But the camp did function as Internierungslager. Because the war had not yet ended and they wanted to prevent chaos, the prisoners remained at the camp for a while longer.

On 12 April 1945 the Canadian liberators arrived at camp Westerbork. The camp was liberated without any resistance. At the time, there were still 876 prisoners, including around 500 Jews. The other prisoners were persons in hiding that were caught. It goes without saying that the prisoners were all delighted about being freed. The Dutch flag was put up. After the war had ended, Van As described it as "one of the best moments" of his life. "The flag was put up while we were singing the national anthem and suddenly I couldn’t feel the ground under my feet any longer. They lifted me up and danced with me up in the air. I couldn’t have thought of a more beautiful liberation."

It would take until the summer of 1945 before all the Jews from camp Westerbork had left. Many of them no longer had family or a home to return to, so first a refugee centre had to be created for them. Besides this, also their identity had to be verified, because they wanted to prevent that any collaborators or Germans could escape by impersonating a Jewish prisoner.

Definitielijst

- International Red Cross

- Name of a complex of co-operating humanitarian organisations which primarily focusses on providing assistance to the sick and wounded military during wartime, to prisoner of war and to civilians during wartime and other conflicts. The role of the Red Cross during World War 2 is somewhat controversial.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

After the war

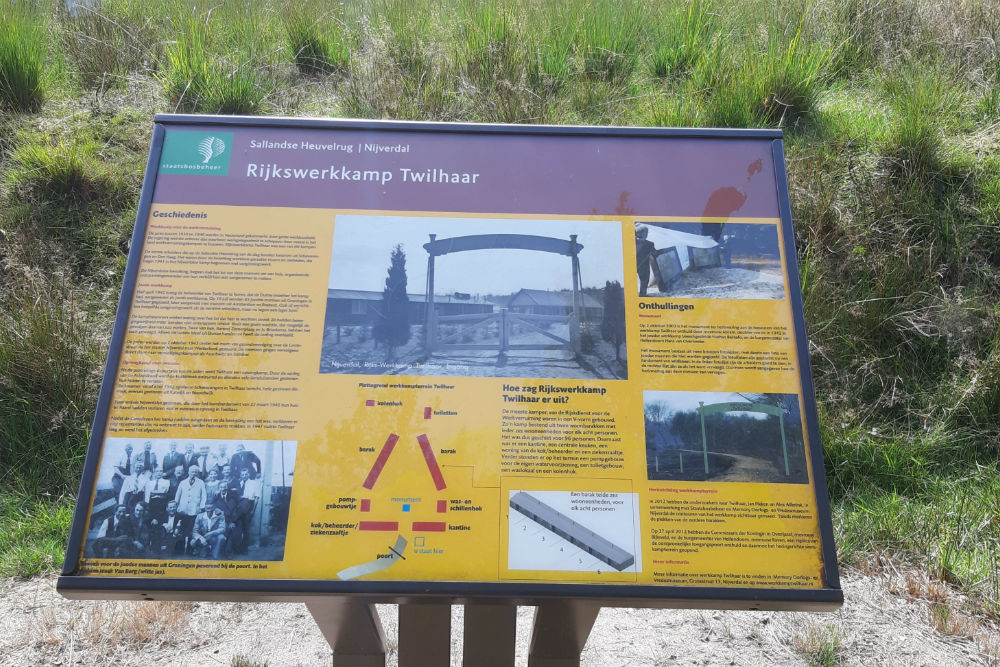

Two weeks after camp Westerbork had been liberated by the Canadians, prisoners of quite a different report arrived at the camp. They were much different than the Jews that had been imprisoned in Westerbork as from 1939. It concerned a group of arrested people from the Dutch national socialist movement, called the NSB. Until 1948, the camp was used as an internment camp for NSB-ers, collaborators and Germans awaiting their trial. When many of them were set free in 1948, the internment camp was discontinued. For a period of approximately one year, Dutch militaries were accommodated in the camp. There is not much information about this short period in the history of camp Westerbork.

As of the summer in 1950 to March 1951 citizens of the former Netherlands East Indies stayed in the former camp Westerbork. The camp was given a new name: ‘De Schattenberg’. After the Dutch government had accepted the independence of Indonesia in December 1949, they had escaped to the Netherlands and received shelter in Westerbork. Meanwhile there were plans to place a monument on the former camp site in memory of the deportations, but the Jewish community didn’t feel the need for it. A plan that did succeed was the installation of a monument in memory of the ten executed resistance fighters, whose remains were found on the former camp site.

The citizens of the former Dutch East Indies did not stay very long in Westerbork. In 1951 a new group of residents arrived: the South Moluccan, mostly military who had served in the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army (KNIL). They too had fled when Indonesia became independent. At the expense of the Dutch government, they were put up at various locations in the Netherlands, including the barracks of the former camps in Westerbork and Vught. At the beginning of the 1960s there lived almost 2,000 Moluccans in the living area ‘Schattenberg’. During that period, the Dutch government decided that the Moluccans had to integrate within the Dutch society, but it wasn’t until 1971 before the last Moluccan family had left the living area.

Plans for demolishing the camp had already been made in the 1960s, but they could only start with it after the Moluccan living area had been discontinued. At the same time, people wondered what destination the former camp site should be given. Proposals included using the former camp site for recreational purposes or as a military exercise area, but the provincial government did not find these proposals suitable. In 1964 they came up with a suitable destination. The foundation Radiostraling van Zon en Melkweg was looking for an area in which they could place satellite dishes. Westerbork was an excellent site for this purpose. One big advantage of installing these satellite dishes here, was that motorised traffic around the site was no longer allowed, because of the interference sensitivity of the equipment. This meant that the peace and quiet of the site could be maintained. As of 1967 a total of twelve radio telescopes were placed.

Although the Jewish community was not in favour of a monument, their attitude changed in the late 1970s. The younger generation of Jews had a greater need for remembering than their parents. In 1970, Queen Juliana revealed the National monument Westerbork at the location where the rail ended in the camp. But, besides the monument, there was nothing else reminding people of what took place at this site. To change this, next of kin of Holocaust victims and other people involved, founded the Work Group Westerbork. Thanks to their efforts, the first scale model of the camp was placed and later information panels. Their wish to also built an information centre, did not however receive much support. But when the former National Institute for War Documentation (RIOD) proposed to create a replica of the exposition about the war times in the Netherlands, which could be seen at the museum in Auschwitz, support for the information centre finally grew. The proposal of the RIOD was carried out and the exposition was housed in the new Memorial Centre Camp Westerbork which was opened by Queen Beatrix on 12 April 1983.

For the first year the anticipated number of visitors to the Memorial Centre Camp Westerbork was 12,000, but it received a staggering 50,000 visitors instead. In the following years, the centre would undergo several adjustments, including the built of an educational room in 1987. In order to fulfil the educational role of the former camp even better, the Memorial Centre was renovated completely in the 1990s. The re-opening took place on 12 April 1999. The interest in the Memorial Centre remained. In 2005, the former camp site received 120,000 visitors, which was a record.

Definitielijst

- Holocaust

- Term for the destruction of European Jewry by the Nazis. Holokauston is the Greek term for a completely burnt sacrifice.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- KNIL

- “Koninklijk Nederlands-Indisch Leger” meaning “Royal Netherlands East Indies Army” (1830-1950). Name of the Dutch army in the Netherlands East Indies.

- NSB

- National Socialist Movement. Dutch political party sympathising with the Nazis.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Images

National Memorial Camp Westerbork Source: Bureau Funeralia / René ten Dam.

National Memorial Camp Westerbork Source: Bureau Funeralia / René ten Dam. Memorial 102.000 Stones Camp Westerbork. Source: Bureau Funeralia / René ten Dam.

Memorial 102.000 Stones Camp Westerbork. Source: Bureau Funeralia / René ten Dam. Barrack 56 Camp Westerbork. Source: Bureau Funeralia / René ten Dam.

Barrack 56 Camp Westerbork. Source: Bureau Funeralia / René ten Dam.Information

- Article by:

- Kevin Prenger

- Translated by:

- STIWOT translator

- Published on:

- 15-06-2015

- Last edit on:

- 30-05-2021

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Related books

Sources

- BLUMENTHAL LAZAN, M. & PERL, L., Vier gelijke stenen, Verbum, Laren, 2006.

- HEYL, B., Het vergeten hoofdstuk, ServicePost, Nieuwekerk a/d IJssel, 2006.

- KNOPP, G., Hitlers Holocaust, Byblos, Amsterdam, 2001.

- KOK, R. & SOMERS, E., Nederland en de Tweede Wereldoorlog, 2005.

- POLAK, J. & SOEP, I., Tussen de barakken..., Uitgeverij Verbum, Laren, 2006.

- PRESSER, J., Ondergang, Aspekt, Soesterberg, 2005.

- SPECTOR, S. & ROZETT, R., Encyclopedie van de Holocaust, Kok, Kampen, 2004.

- VUIJSJE, I., Tegen beter weten in, Augustus, Amsterdam, 2006.

- MULDER, D., Kamp Westerbork, Hooghalen, Herinneringscentrum kamp Westerbork, 2003.

- VEEN, H. van der, Westerbork 1939 - 1945 Het verhaal van vluchtelingenkamp en Durchgangslager Westerbork, Hooghalen, Herinneringscentrum Kamp Westerbork, 2003.

- www.annefrank.org

- www.cympm.com

- www.deathcamps.org

- www.kamparchieven.nl

- www.kampwesterbork.nl

- www.verzetsmuseum.org