Introduction

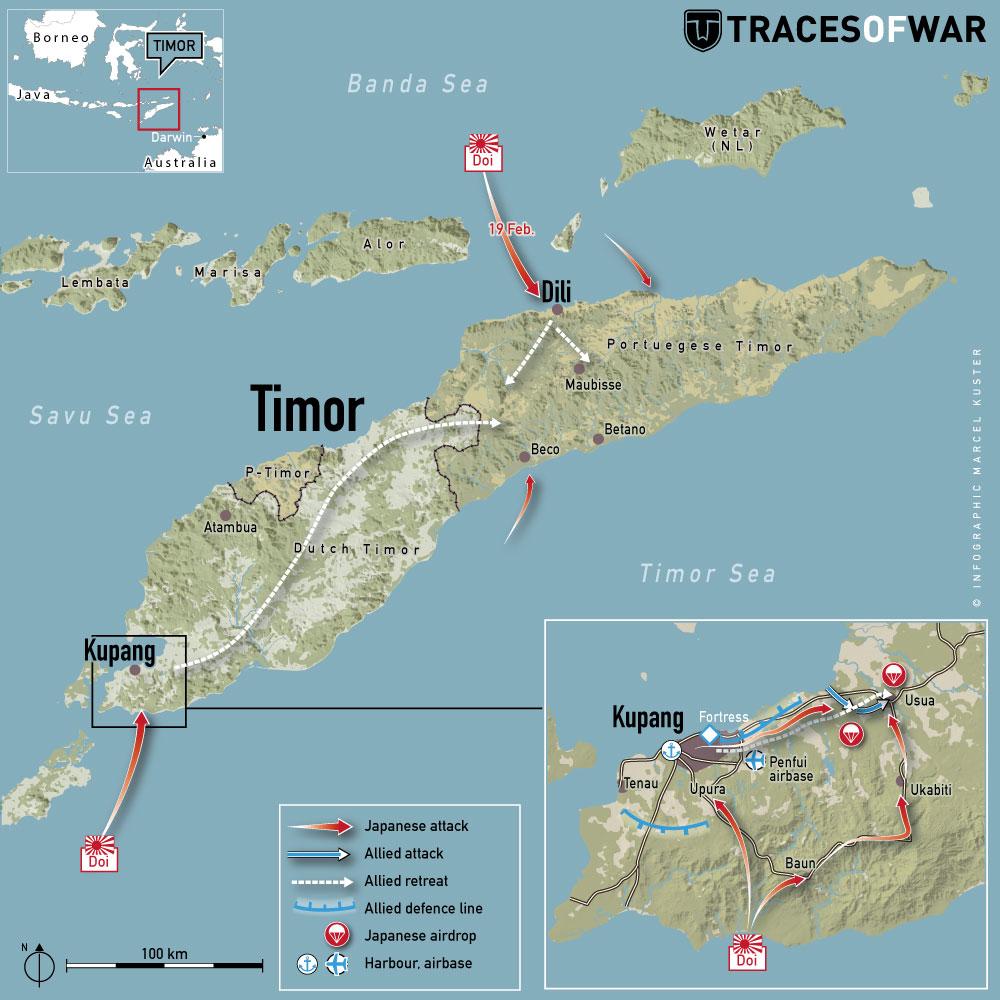

The island of Timor, situated about 700 kilometers (approx. 380 nm) northwest of the Australian city of Darwin, was divided in 1942 between two colonial powers. The eastern half of the more than 30,000 km² large surface of the island was a Portuguese possession whereas the western half belonged to the Dutch East Indies. Almost immediately after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, on December the 7th, 1941, the allies decided to occupy the neutral Portuguese part in order to prevent the Japanese from conquering it with the purpose to establish a bridgehead.

In the night of 19 to 20 February, 1942, two Japanese invasion armies landed at Kupang, the capital city of Dutch Timor and near Dili, the capital of Portuguese Timor. Following this, the allied forces on Timor were quite soon beaten by the Japanese superior power and the majority surrendered. Several hundreds of the Australian troops and of the Royal Dutch East-Indies’ Army (KNIL) succeeded however to escape and started a guerilla warfare against the Japanese occupying forces. Only by the 20th of April, 1942, the allied forces were able to communicate, by means of an improvised radio, to their own army headquarters (HQ) that they were still not defeated. From that moment onwards the guerillas were supplied by air by airplanes of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF). From May onwards relieve parties and supplies were provided by the Australian navy.

The Dutch and Australian troops have, with interchanging success, kept up the battle with the Japanese on Timor for almost ten months. They demolished bridges, attacked Japanese patrols and guards, conquered enemy stores and placed mines. In this way they succeeded, with primitive means, to be derogatory to the enemy.

By the end of 1942 the Japanese had sent so many troops to Timor in order to break the allied resistance that it became necessary to evacuate all guerillas as well as their native supporters and Portuguese colonists who had fought on the side of the allies. Several trials to achieve this were carried out by the Australian navy; some successful others failed. During these trials a corvette was lost at the cost of 100 lives.

After that, the Australians requested a fast and well-armed vessel from the Dutch Admiralty in order to evacuate the troops from Timor. The two Dutch destroyers Hr. Ms. Van Galen (2) and Tjerk Hiddes were stationed in Fremantle since a short time. But as the ‘Van Galen’ was at sea, ‘Tjerk Hiddes’ was charged with the dangerous mission. Hr. Ms. Tjerk Hiddes required three dangerous trips to evacuate all guerillas and their collaborators. The daring crossings resulting in the successful evacuations were highly praised by all allies.

Definitielijst

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- KNIL

- “Koninklijk Nederlands-Indisch Leger” meaning “Royal Netherlands East Indies Army” (1830-1950). Name of the Dutch army in the Netherlands East Indies.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Images

Australian guerillas receive fruit from Timorese inhabitants. Source: Australian War Memorial.

Australian guerillas receive fruit from Timorese inhabitants. Source: Australian War Memorial. Allied guerilla on his way accompanied by Timorese helpers. Source: Australian War Memorial.

Allied guerilla on his way accompanied by Timorese helpers. Source: Australian War Memorial.Allied troops on Timor

Before the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Australian and Dutch governments had already agreed that Australia would supply troops in order to help defend Dutch Timor in case Japan would get involved in the war. As a consequence already on December 12, 1941, a 1,400 strong detachment of the Australian army arrived in Kupang. This unit was called “Sparrow Force “ and was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel W. Legatt. Sparrow Force consisted mainly out of the Australian 8th Division’s 2/40th Battalion and of commandos of 2nd Independent Company . Already 650 men of the KNIL were present in Kupang under the command of Lieutenant Colonel N. van Straten . This force was furthermore supported by 12 Lockheed Hudson light bomber aircraft of No.2 Squadron RAAF and a small unit of the British Royal Artillery’s 79th Anti-Aircraft Battery.

The Dutch East Indian and Australian governments had decided to occupy East Timor almost immediately after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December, 1941, in order to prevent the Japanese from conquering this neutral territory. On 15 December Hr. Ms. Soerabaja anchored at Kupang . During the night 200 KNIL soldiers and 200 troops of the Australian Imperial Forces boarded the Dutch vessel. The next morning the old ship proceeded towards Dili, preceded by Hr. Ms. Canopus of the militarized “Governmental Navy” [consisting of requisitioned merchant ships]. On board this ship were a Dutch and an Australian negotiations officer. On 17 December the ships arrived off the coast of Dili, but the Soerabaja waited outside the territorial waters. The Canopus put the negotiations officers ashore at Dili where they asked the Portuguese governor, Ferreira de Cavalho, to allow the allied troops access to the city. The Governor asked for one hour’s time for reflection. But when this hour was past and a positive answer was not available for the time being, Hr. Ms. Soerabaja steamed up towards 100 yards off the coast at Dili and the disembarking of the troops started. Approximately one hour later, around 12:45, the 400 allied soldiers had landed and the Soerabaja positioned itself in order to intervene with both 28cm guns if so required. The Portuguese dictator, Antonio de Salazar, protested with the allied governments and the Portuguese governor declared himself prisoner. In this way, the Portuguese tried to emphasize their neutrality but in fact they did not rebuke the allied occupation. The 500 men of government troops did not interfere while the Portuguese colonists and the Timorese civilians welcomed the allies.

In January 1942 most of the KNIL soldiers under Van Straten and the whole of the 2nd Independent Company under Major A.Spence were transferred to Portuguese Timor where they were dispersed over the area in small groups. On 12 February more reinforcements arrived in Kupang by means of Australian staff members. Among the staff officers was Brigadier W. Veale who was appointed Commanding Officer on Timor.

From 26 January Timor was bombed regularly by Japanese aircraft which were only marginally opposed by a squadron of P-40s of the US Army Air Corps which had a basis in Darwin. From February the air strikes became more intensive. On the 16th of February a convoy with reinforcements and supplies for Timor on its way to Kupang was attacked by Japanese planes. In spite of the fact that the convoy was escorted by the heavy American cruiser USS Houston and the American destroyer USS Peary and the Australian gun boats HMAS Swan and HMAS Warrego, who all together had a lot of anti-aircraft fire power available, the convoy was forced to return to Darwin.

In the night of 19 to 20 February a part of the 228th Regimental Group of the Imperial Japanese Army landed on Timor under the command of Colonel Sadishichi Doi. The first contact was near Dili where the Japanese ships were erroneously taken to be the ships that carried the expected Portuguese reinforcements from Mozambique. In spite of the fact that the defenders of Dili, consisting of the Dutch KNIL soldiers of Van Straten and the Australian Commando troops of the 2nd Independent Company were surprised, they started a well-organized withdrawal. Herewith the retreat was covered by various small groups of commandos. One of those units, consisting of 18 men and which was stationed at the local airport succeeded in killing almost 200 Japanese soldiers during the first hours of the battle. The Australian commando troops withdrew towards the mountains and approximately 200 KNIL soldiers under Van Straten moved in south westerly direction towards the border with Dutch Timor.

During the same night the allied troops in Dutch Timor were heavily bombed which forced the 12 light bombers of the RAAF back to Darwin. The bombardment was followed by amphibian landings by the largest part of the Japanese 228th Regimental Group on the hardly defended south west part of the island near the river Paha. The Japanese infantry was supported by light armored tanks and advanced quickly towards the north so the defenders of Kupang became encircled. The headquarters of Sparrow Force was quickly transferred to the east and stayed out of range.

Lieutenant Colonel Leggatt immediately ordered the airport near Kupang to be destroyed but this was prevented by the 500 Japanese parachutists of the 3rd Yokosuka Special Naval Force. The Sparrow Force HQ was even further transferred to the east and Legatt’s troops attacked the Japanese paras. In the morning of 23 February over 400 Japanese para troops were eliminated but behind Sparrow Force the Japanese infantry had progressed so much that the Australian were threatened to become surrounded. Legatt conferred with his men who were virtually exhausted and who had almost run out of ammunition. Because they had also a large number of wounded the Japanese invitation to surrender was accepted. Almost 1200 primarily Australian soldiers were made prisoner of war and disappeared into prison camps which had been hastily constructed on Timor.

Brigadier Veale, together with his men of the Sparrow Force HQ and a number of Dutch military, in total a force of about 250 strong, proceeded further in easterly direction in order to try to contact the commandos of the 2nd Independent Company.

Definitielijst

- Commando troops

- Special forces, deployed especially for missions behind enemy lines such as sabotage and reconnaissance.

- cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

- destroyer

- Very light, fast and agile warship, intended to destroy large enemy ships by surprise attack and eliminating them by using torpedoes.

- Doi

- Died of injuries.

- infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- KNIL

- “Koninklijk Nederlands-Indisch Leger” meaning “Royal Netherlands East Indies Army” (1830-1950). Name of the Dutch army in the Netherlands East Indies.

- neutrality

- Impartiality, absence of decided views, the state of not supporting or helping either side in a conflict.

- Squadron

- A military unit in the Belgian navy usually six to eight small ships operating together under one command. The smallest military unit in the Dutch air force of about 350 men. In most countries is the designation of a military unit thesize of a company. It is either an independent unit, such as a battery, or part of a bigger Calvary unit. In the air force it is the designation of a unit of aircrafts.

Images

Brigadier W.C.D. Veale. Source: Australian War Memorial.

Brigadier W.C.D. Veale. Source: Australian War Memorial. Officers of the 2nd Independent Company. On the left Major, later on Lieutenant-Colonel, Spence. Source: Australian War Memorial.

Officers of the 2nd Independent Company. On the left Major, later on Lieutenant-Colonel, Spence. Source: Australian War Memorial. Left: Lieutenant-Colonel N.L.W. van Straten. Source: Australian War Memorial.

Left: Lieutenant-Colonel N.L.W. van Straten. Source: Australian War Memorial. Japanese para troopers land near the airport of Kupang February 1942 Source: Dutcheastindies iblogger.

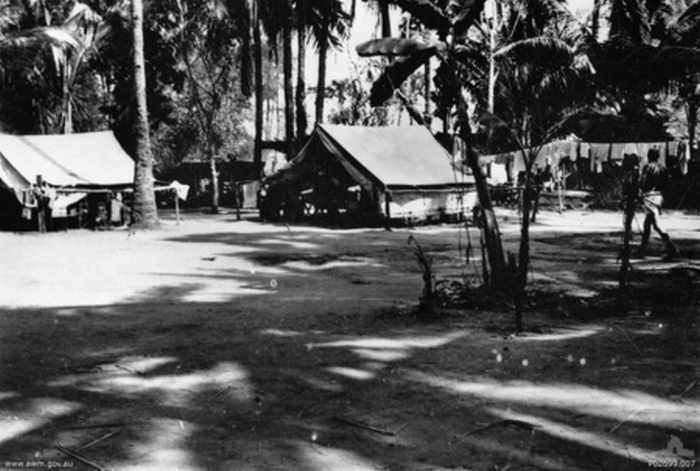

Japanese para troopers land near the airport of Kupang February 1942 Source: Dutcheastindies iblogger. Oesapa Besar. Prisoner of war camp on Timor. Source: Australian War Memorial.

Oesapa Besar. Prisoner of war camp on Timor. Source: Australian War Memorial.Guerilla war with the Japanese

End February the Japanese occupying forces were ruling the larger part of Dutch Timor and the surroundings of Dili in Portuguese Timor. The allied forces, although spread out, were still in control in the mountains. The Australian commando troops under Major Spence regularly attacked with quick hold-ups the Japanese assisted by Timorese guides, bearers and their small but tough mountain ponies. Although the Portuguese colonial authorities were officially still neutral, the Portuguese colonists and the natives were sympathetic towards the allies. These could therefore use the local telephone lines in order to communicate with each other and to gather information on the enemy troop movements. The Australians however could not contact their home country because they did not have the availability of the appropriate radio equipment.

Colonel Doi sent David Ross, the Australian Consul in Portuguese Timor who at the same time was the local Qantas agent, to the Australian commandos with the demand to immediately surrender. Major Spence however refused profoundly after which Ross provided him with the positions of the Japanese units. Apart from that he gave Spence a letter made up in Portuguese which stated that each and every citizen who assisted the commando troops, later on could claim Australian citizenship.

A few weeks later the groups of Major Spence and Lieutenant Van Straten met in Atamboea, in the north of Dutch Timor. Together the allied troops consisted out of some 650 men. The allied leaders discussed the situation and concluded that that such a big group of military was too vulnerable in an area that was largely controlled by the enemy. Apart from that, the supplying would create too much of a problem. Therefore they agreed that they would split up in groups of 6 to 9 men and to change into a guerilla warfare. The KNIL military would spread out over Dutch Timor and the Australian troops would be splitting up in Portuguese Timor.

In Australia in the meantime nothing was known about the activities of the Dutch and the Australian guerillas. After the occupation of Timor all allied military, who were not made prisoner of war or had not been able to flee across the sea, had been officially reported missing-in-action, most likely killed-in-action. Towards the second half of April however some Australian commandos had been able to construct an emergency radio with parts of their own and with stolen parts from the Japanese. With this radio which was called ‘Winnie the War Winner’ from 20 April regularly contact was made with Australia. From the beginning of May the guerillas were supplied on a regular basis by Australian aircraft and naval ships.

On May 24th Brigadier Veale and Lieutenant Van Straten were flown to Australia by Catalina sea plane for a tactical conference. The command of the guerilla forces had been transferred to Major Spence, who got promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and who became CO on Timor and to Captain-of- Infantry Breemouer.

In June American General Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander in the South Pacific, received a report from General T.Blamey, the Allied Supreme Commander of the land armies. The report recommended to continue the guerilla warfare instead of carrying out a large scale invasion in order to disturb the Japanese on Timor. MacArthur turned the recommendations into orders and decided that, only when their positions became untenable, they were to withdraw the guerillas. This meant that, next to supplying, also logistics regarding relieve and possible reinforcements had to be taken care of.

Most of the supply trips from Australia to occupied Timor were made by two assist ships of the Australian navy. The Kuryu and the Vigulant. The Kuru was a wooden ship of only 55 tons and a length of 23 meters which had been requisitioned in December 1941. Between May and November 1942 this ship made eight successful trips to Timor and carried hundreds of tons of supplies to Timor and repatriated dozens wounded and sick military as well as Portuguese refugees. The Vigilant, a seized small customs ship made three successful trips between July and early September.

Colonel Doi sent David Ross again towards the Sparrow Force with the message that he nursed great admiration for the allied guerilla campaign until now, but that time had come for an unconditional surrender. The Japanese commander compared the campaign with the one of the Afrikaner commandos in the Boer War in South Africa and realized that he would need at least a ten times stronger force to beat the allies. But furthermore Doi stated that he expected reinforcements and that he would defeat the guerillas after all. The commando troops however did not want to hear about surrendering and this time Ross did not return to Dili, which was a message in itself. On July 16th he was evacuated to Australia.

Definitielijst

- commando troops

- Special forces, deployed especially for missions behind enemy lines such as sabotage and reconnaissance.

- Doi

- Died of injuries.

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- KNIL

- “Koninklijk Nederlands-Indisch Leger” meaning “Royal Netherlands East Indies Army” (1830-1950). Name of the Dutch army in the Netherlands East Indies.

Images

Australian commando troops of the 2nd Independent Company during their guerilla campaign. Source: Australian War Memorial.

Australian commando troops of the 2nd Independent Company during their guerilla campaign. Source: Australian War Memorial. Australian guerillas on Timor 1942. Source: Australian War Memorial.

Australian guerillas on Timor 1942. Source: Australian War Memorial. Winnie the War Winner. Source: Australian War Memorial.

Winnie the War Winner. Source: Australian War Memorial. Australian guerillas on Timor taking a break. Source: Australian War Memorial.

Australian guerillas on Timor taking a break. Source: Australian War Memorial. HMAS Kuru. Source: Wikipedia.

HMAS Kuru. Source: Wikipedia.Japanese offensive and allied losses

From the beginning of August the battle became a lot tougher for the guerrillas. The consequences of the experienced suffering and illnesses accumulated. Of about 250 KNIL soldiers only some 150 remained. The other 100 had been killed, imprisoned or left behind heavily wounded. The guerillas had to be in constant motion which not only hampered the transport of the wounded but also the supply and communication.

From that time onwards the Japanese constantly increased their reinforcements. They had suffered serious losses in the meantime by the actions of the guerillas, approximately 1,000 dead, and they wanted to settle the account for once and for all. For that purpose they turned into a tactic of the scorched earth. They started to bomb dozens of villages or to burn them to the ground, which cost many civilians their lives. Furthermore the Japs recruited more and more Timorese especially for functions as spies or guides, by means of threats and intimidation.

The commander of the Japanese 48th Division, Lieutenant General Yuichi Tsuchihashi arrived at Timor around that time in order to lead the campaign against the guerillas with the aid of the reinforcements. Most parts of Timor were cleared of guerillas who were driven away to ever decreasing areas. During September the full strength of the Japanese 48th Division arrived.

Also the Australians sent reinforcements. The 450 men strong 4th Independent Company came to relieve the weakened 2nd Independent Company. The Australian destroyer HMAS Voyager put this company ashore in the last week of September near Betano on Timor. While the disembarkation was in full swing the Australian ship which had been built in 1918, ran aground on a reef. In spite of desperate tries to disengage the ship, the Australians had to abandon ship when they were attacked by Japanese aeroplanes. The destroyer was put on fire and destroyed. The crew was picked up by two Australian mine sweepers but the remaining commando troops of the 2nd Independent Company could not be evacuated.

Also the Dutch forces would be relieved by a 63 men strong detachment which had been composed in Australia and was commanded by the 1st Lieutenant of the Infantry Stoll. To carry the Dutch soldiers to Timor and to evacuate the 2nd Independent Company and the Portuguese refugees, next to the small ship Kuru, the Australian corvettes of the Bathurst class HMAS Castlemaine and HMAS Armidale were appointed. The operation was delayed by bad weather and by Japanese air attacks on both the corvettes. The Kuru however could embark 77 Portuguese women and children and transfer to HMAS Castlemaine who evacuated them to Darwin. The Armidale however, with the Dutch troops onboard was hit by two Japanese air torpedoes and sunk. Around one hundred of the 149 crew lost their lives during this disaster.

Definitielijst

- commando troops

- Special forces, deployed especially for missions behind enemy lines such as sabotage and reconnaissance.

- destroyer

- Very light, fast and agile warship, intended to destroy large enemy ships by surprise attack and eliminating them by using torpedoes.

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- KNIL

- “Koninklijk Nederlands-Indisch Leger” meaning “Royal Netherlands East Indies Army” (1830-1950). Name of the Dutch army in the Netherlands East Indies.

- mine

- An object filled with explosives, equipped with detonator which is activated by either remote control or by colliding with the targeted object. Mines are intended to destroy of damage vehicles, aircrafts or vessels, or to injure, kill or otherwise putting staff out of action. It is also possible to deny enemy access of a specific area by laying mines.

- tactic of the scorched earth

- The method involved destroying everything that could be any use for the enemy during the retreat.

Images

The burnt out wreck of HMAS Voyager on the coast of Timor near Betano 23 September, 1942. Source: Australian War Memorial.

The burnt out wreck of HMAS Voyager on the coast of Timor near Betano 23 September, 1942. Source: Australian War Memorial. HMAS Armidale. Source: Australian War Memorial.

HMAS Armidale. Source: Australian War Memorial. HMAS Castlemaine. Source: Australian War Memorial.

HMAS Castlemaine. Source: Australian War Memorial.Visual overview of the battle

Images

Hr. Ms. Tjerk Hiddes: Timor Ferry

Possibly the Australian navy had underestimated the risks of an evacuation and drew the conclusion that it required a fast en well-armed ship to finish such exercise successfully. Because the Australian did not have such ship available at that moment, the Dutch Commander of the Navy, Rear-Admiral Coster, was called upon. Coster supported the plans to evacuate the guerillas from Timor and because Hr. Ms. Van Galen (2) was at sea, he appointed Hr. Ms. Tjerk Hiddes to carry out this dangerous mission. The commander of the Tjerk Hiddes, Lieutenant Commander J.W.Kruys, received secret orders to firstly sail to Port Darwin where they had to bunker oil and where two motor launches and eight collapsible boats had to be loaded. On December 5th, 1942, the modern destroyer left her base, Fremantle, West Australia. Apart from fuel and the launches, commander Kruys received extremely useful information from the RAAF in Darwin. Shortly before, the Australian Air Force had downed a few Japanese bombers which had enabled them to lay their hands on a flight schedule of Japanese air patrol activities between North Australia and Timor. Therefore Kruys had the availability of detailed data regarding the air routes and times of the Japanese reconnaissance flights. Experience thought him also that the Japanese would not quickly divert from their schedules.

On the 9th of December, early at 5 in the morning, Hr. Ms. Tjerk Hiddes left Port Darwin and headed for Timor by strait Dundas, between Melville Island and the Cobourg peninsula, after which the destroyer crossed the Timor Sea with a speed of thirty knots. For the first hours Australian Bristol Beaufighters accompanied them. It had been agreed with Captain-of-Infantry Breemouer that he would gather his men and other refugees on the beach at Betano, where they would ignite three large fires. By excellent navigating and timing Hr. Ms. Tjerk Hiddes arrived exactly in time on the right spot. Commander Kruys and his navigation officer Lieutenant Keesom had used their artillery radar in order to sound out the coast line and the Asdic-installation to detect reefs and cliffs, which were very innovative methods.

The Tjerk Hiddes anchored 800 yards from the coast and at that time the motor launches and 4 of the foldable boats had been prepared to be lowered. Thereafter the remainder of the foldable boats were hung outside board. The motor launches tugged the eight foldable boats into the surf after which the men of the landing detachment of the Tjerk Hiddes rowed them ashore. The KNIL soldiers on the beach were excited to be evacuated by a Dutch ship. The motor launches and the folding boats had to repeat their trips twice in order to embark all evacuees on the Hiddes. At the same time several Australian commandos and supplies were put ashore as reinforcements of the guerillas. Even before 01:00 all refugees, 50 women and children, 50 sick and wounded and almost 300 Australian and Dutch soldiers were onboard and the launches, boats and climbing nets cleared and stowed inboard. A quarter of an hour later the Hiddes went anchor up to return to Australia with a speed of 30 knots, whereby the heavy monsoon rains provided appropriate cover after daylight. The whole of the operation could not have been carried out more efficiently by the very best trained commando troops.

Several days after its return in Port Darwin, on 14 December, Tjerk Hiddes again left towards midnight in order to pick up evacuees; again accompanied by Beaufighters. This time the agreed landing spot would be 8 miles east of Betano and it concerned mainly the 2nd Independent Company. Again by excellent navigation, around 22:00 the pick-up zone was reached and within five minutes the launches and folding boats were on their way with five tons of supplies for the troops of the 4th Independent Company. Towards 00:30 all persons to be evacuated, about 240 Australian commandos and 30 Portuguese clergymen were onboard and the destroyer ready to leave. Again under the cover of the monsoon storms, the Dutch vessel crossed the Timor Sea and was again escorted by the Beaufighters at the last stretch. After again an exemplary mission, the Tjerk Hiddes entered Port Darwin around 17:00 on 16 December 1942.

Already the next night Hr. Ms. Tjerk Hiddes left for the third and last time for Timor. This time Portuguese colonists and Timorese civilians had to be collected at Aliambeta, on the south coast of Timor. Around 23:00 on December 18th, the first signals were exchanged with the people on the beach and half an hour later the disembarking of aid materials started and the boarding of the more than 310 evacuees and 4 tons of valuable rubber. Even before 01:00 the Dutch destroyer was again ready for departure. In the early hours of 19 December the Beaufighters appeared over the ship which docked around 11:00 in Port Darwin.

The Timor-operation by the Tjerk Hiddes was a complete success and the way it had been carried out was an example of effective military performance. During the three trips to and from Timor not a single Japanese plane had been spotted, which had not been due to fortune but to the clever avoidance of the Japanese reconnaissance flights by the intelligence about their flight schedules. The excellent maneuvering and the quick unloading and loading of the folding boats and motor launches made the success of the operation complete. In an article of February 1960, in the American magazine US Naval Institute Proceedings, the Timor operation of Hr. Ms. Tjerk Hiddes was extensively analyzed and the vessel was called the Timor-ferry.

Definitielijst

- commando troops

- Special forces, deployed especially for missions behind enemy lines such as sabotage and reconnaissance.

- destroyer

- Very light, fast and agile warship, intended to destroy large enemy ships by surprise attack and eliminating them by using torpedoes.

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- KNIL

- “Koninklijk Nederlands-Indisch Leger” meaning “Royal Netherlands East Indies Army” (1830-1950). Name of the Dutch army in the Netherlands East Indies.

- radar

- English abbreviation meaning: Radio Detection And Ranging. System to detect the presence, distance, speed and direction of an object, such as ships and airplanes, using electromagnetic waves.

Images

Australian Beaufighters. Source: Australian War Memorial.

Australian Beaufighters. Source: Australian War Memorial.Conclusion

In the first week of January 1943 it was decided to also withdraw the commando troops of the 4th Independent Company from Timor, because in the meantime 12,000 Japanese troops were present on the island. With the success of Hr. Ms. Tjerk Hiddes in mind, the Australian navy decided to have the modern Australian destroyer HMAS Arunta carry out the evacuation. There was a very strong surf when the Australian destroyer, deep in the night of 9 to 10 January, anchored at the south coast of Timor. Still they succeeded in boarding the 282 Australian guerillas and 30 Portuguese colonists. Many of them had been forced however to swim through the surf towards the folding boats as these could not reach the beach. On January 10, HMAS Arunta moored safely in Port Darwin.

A small team of the Australian intelligence department which was known as S-force and a small group of the 4th Independent Company were left behind on Timor. Their orders were to spy on the Japanese and to monitor their troop movements and composition. Their presence however was quite soon discovered by the enemy and on 10 February 1943 they were evacuated by the American submarine USS Gudgeon. Herewith the presence of allied troops on Timor came to an end. The guerillas and their Portuguese and Timorese partners had prevented a whole Japanese division of 12,000 men from joining the, for the Japanese so crucial, New Guinea campaign. A very high price was paid for this: apart from the killed allied soldiers, 40,000 to 70,000 Timorese were killed or missing and many villages on Timor were largely destroyed.

In the course of December1942 it was still considered to give it a try to recapture Timor. A possible invasion would in that case have to take place between April and October 1943. Plans for this were being worked out by several British, Australian and American staff officers. On 25 January, 1943, MacArthur decided however that a reconquering for the time being was not a prospect. The priorities were elsewhere.

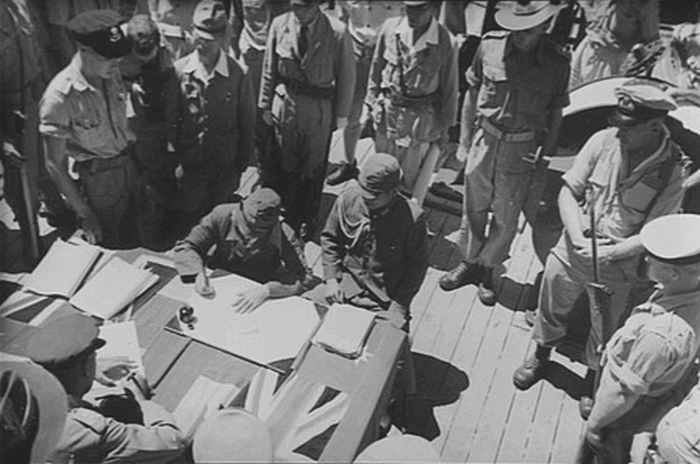

It would never come to a recapturing of Timor and the Japanese stayed in control of the island till the capitulation of Japan in August 1945. Some weeks later, on September 11th, the Japanese commander on Timor, Colonel Tatsuichi Kaida, signed for the capitulation of Timor aboard the Australian gun boat HMAS Moresby.

Definitielijst

- capitulation

- Agreement between fighting parties concerning the surrender of a country or an army.

- commando troops

- Special forces, deployed especially for missions behind enemy lines such as sabotage and reconnaissance.

- destroyer

- Very light, fast and agile warship, intended to destroy large enemy ships by surprise attack and eliminating them by using torpedoes.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

Images

HMAS Arunta. Source: Wikipedia.

HMAS Arunta. Source: Wikipedia. The Japanese commander on Timor Colonel Tatsuichi Kaisa sign the capitulation onboard HMAS Moresby. Source: Australian War Memorial.

The Japanese commander on Timor Colonel Tatsuichi Kaisa sign the capitulation onboard HMAS Moresby. Source: Australian War Memorial. Destruction at Kupang. Source: Wikipedia.

Destruction at Kupang. Source: Wikipedia. Bomb damage of the cathedral of Dili early 1946. Source: Australian War Memorial.

Bomb damage of the cathedral of Dili early 1946. Source: Australian War Memorial.Information

- Article by:

- Peter Kimenai

- Translated by:

- Fred Bolle

- Published on:

- 05-01-2013

- Last edit on:

- 30-09-2024

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Related books

Sources

- BEZEMER, K.W.L., Verdreven doch niet verslagen, Uitgeversmaatschappij W. de Haan N.V., Hilversum, 1967.

- BOSSCHER, PH., M., De Koninklijke Marine in de Tweede Wereldoorlog deel 3, Uitgeverij T. Wever B.V., Franeker, 1990.

- MARK, C., Schepen van de Koninklijke Marine in W.O. II, De Alk bv, Alkmaar, 1997.