Introduction

Hr. Ms. K XVII was a Dutch submarine of the K XIV class. The K-boats were especially designed and built for service in the Dutch East Indies. (K stands for Koloniaal = Colonial). The series started in 1913 with the K I which was constructed at the shipyard The Royal Scheldt in Flushing (De Koninklijke Maatschappij De Schelde). The development of the K-ships was running parallel to the one of the O-ships (submarines = Onderzeeboten). Those vessels however were developed for services in European waters. The K I was tugged to the Far East in 1916 by sea going tugboat ’Witte Zee’ but in 1920 Hr. Ms. K III made this trip for the first time all on its own.

The submarines K VII up to and including K X became an improved version of the first series K-boats. With their 715 ton displacement-under-water they were a measure larger than the first series. The design however was still of the “Single Hull” type and they still had 45cm torpedoes as their primary armory. The 7.5cm deck gun was replaced by an 8.8cm gun which could also be used as an anti-aircraft gun.

The next series K-boats, K XI, K XII and K XIII was the first series that was completely designed by Ir. (engineer) J.J. van der Struyff and were taken into service in 1925 and 1926.These submarines were again 100 ton larger and were calculated to sustain a depth of 60 meters (approx. 33 fathom). The series was still in service during the outbreak of the Second World War. Hr. Ms. K XI and K XII have been taken out of service towards the end of the war. On 21 December 1941, an explosion occurred aboard K XIII resulting from battery gas (escaped hydrogen gas from the batteries) which caused three deaths. On March 2nd, 1942, the unrepaired sub was demolished at the Naval establishment in Surabaya, Java, by navy personnel.

The last series of the K boats was also developed by Ir. Van der Struyff being a very successful design. The series consisting of the K XIV up to and including K XVIII contained 200 ton more water displacement compared to the preceding series and were capable of a diving depth up to 80 meters [approx. 44 fathom]. Also these five K-boats were the first ones to be equipped with eight torpedo tubes of 53cm. Hr. Ms. K XIV was very successful when, on 23 December, 1941 four Japanese freighters were sunk near Kuching, in the Malaysian part of Borneo. The submarine survived the war together with its sister ship Hr. Ms. K XV and both ships were laid up in 1946. Also K XVI booked a great success when she succeeded in sinking the Japanese destroyer Sagiri, also near Kuching. Unfortunately the boat got lost a day later by a torpedo strike of the Japanese submarine I 66. Hr. Ms. K XVIII was heavily damaged by enemy depth charges on 23 January 1942 and was demolished on March 2nd of the same year by navy personnel at the Naval establishment in Surabaya.

For a long time nothing was known about the fate of Hr. Ms. K XVII. The submarine did not return from a patrol which she had started, under British naval command on December 6th, 1941, together with Hr. Ms. O 16. The patrol carried both Dutch ships to the South Chinese Sea, east of the mainland of Malaysia. On 14 December K XVII encountered K XII and was warned about a Japanese submarine which was supposed to be in the area. That was the last time K XVII was seen. Up to 21 December regular radio contact existed between the sub and the allied naval command. From that day onwards nothing has ever been heard from Hr.Ms. K XVII anymore and it was assumed that the ship had run into a Japanese mine.

The uncertainty about the fate of K XVII was increased when in 1980, a disguised man appeared in a Dutch TV program and stated that he had blown up the Dutch submarine by orders of Winston Churchill and with the knowledge of Franklin Roosevelt and Queen Wilhelmina (of the Dutch Government in exile). The Dutch interviewer suggestively asked whether this could probably concern the missing K XVII. The interviewee did not answer this.

In 1996, the book “Operation JB” by Christopher Creighton was published in which the author makes a statement about the fate of Hr. Ms. K XVII. The Dutch sub was supposed to have been blown up by the British secret service because the crew of the boat was estimated to have discovered the Japanese fleet on its way to Pearl Harbor. Churchill wanted the Japanese attack on the Pacific fleet in Hawaii to be successful and therefore it had to remain a secret. A successful surprise attack on the battle ships in Pearl Harbor would draw the American population from their isolation and the United States of America would become involved in the Second World War. This should also be the wish of the American President and therefore the leaders agreed that the Dutch submarine and its crew ought to disappear. Christopher Creighton and the disguised man on Dutch TV appeared to be the same person.

Definitielijst

- destroyer

- Very light, fast and agile warship, intended to destroy large enemy ships by surprise attack and eliminating them by using torpedoes.

- mine

- An object filled with explosives, equipped with detonator which is activated by either remote control or by colliding with the targeted object. Mines are intended to destroy of damage vehicles, aircrafts or vessels, or to injure, kill or otherwise putting staff out of action. It is also possible to deny enemy access of a specific area by laying mines.

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

Images

Hr. Ms. K XVII before World War Two

On June 1st, 1931 the keel of the K XVII was laid out on the shipyard of Feijenoord in Rotterdam as construction number 322 and a year later, on 26 July 1932, she was launched. On 19 December, 1933, the new submarine entered service with Lieutenant Commander C.W. Slot and his 36 strong crew.

Between 20 June and 1 August, 1934, a Dutch squadron which consisted of Hr. Ms. Evertsen, Hr.Ms. Hertog Hendrik and Hr. Ms. Z 5, made a ‘showing the flag’ trip to the Baltic Sea. Also the new submarines Hr. Ms. K XVII and K XVIII were allocated to this flotilla. The following ports were visited: Gdynia, Königsbergen, Riga and Copenhagen. Lieutenant Commander J.A. de Gelder had been appointed commander of the K XVII in the same year.

Hr. Ms. K XVII departed for the Dutch East Indies in January 1935, together with her sister ship Hr. Ms. K XVI. The route went along Lisbon, Napels, Alexandria, Aden and Colombo. On the way the crew was allowed shore leave and , amongst others, Vatican City and the pyramids of Cheops were visited. On March 26th, 1935, both Dutch ships arrived in Padang, Sumatra. On April 4, both submarines arrived at their temporarily final destination in Surabaya, on Java. In Dutch East Indies, Lieutenant Commander E.H. Vorster took command of Hr. Ms. K XVII.

From 17 January 1938 onwards Hr. Ms. K XVII formed part of the ‘Division Submarines I’ under the command of Lieutenant Commander J.A. van Gelder. Commander of the K XVII at that moment was Lieutenant Commander A. van Karnebeek. On December 6th , 1938, the sub participated in the Surabaya naval review at the occasion of the 40th anniversary of the reign of HM Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands. Twenty Dutch warships and three ships of the Governmental Navy (Gouvernements marine = merchant ships requisitioned by the navy) were saluting the Commander of the naval forces in Dutch East India, Vice Admiral Ferwerda, the French Vice Admiral of the squadron Le Bigot and Governor Ch.O. van der Plas of East Java.

Definitielijst

- squadron

- A military unit in the Belgian navy usually six to eight small ships operating together under one command. The smallest military unit in the Dutch air force of about 350 men. In most countries is the designation of a military unit thesize of a company. It is either an independent unit, such as a battery, or part of a bigger Calvary unit. In the air force it is the designation of a unit of aircrafts.

Images

Hr. Ms. Evertsen, Z 5, Hertog Hendrik, K XVII en K XVIII in Riga Lithuania from 12 till 16 July 1934. Source: Collection van Cleemputte.

Hr. Ms. Evertsen, Z 5, Hertog Hendrik, K XVII en K XVIII in Riga Lithuania from 12 till 16 July 1934. Source: Collection van Cleemputte. Part of the crew of Hr. Ms. K XVII en K XVI on an audience in Vatican City on 20 January, 1935. Source: Collection van Cleemputte.

Part of the crew of Hr. Ms. K XVII en K XVI on an audience in Vatican City on 20 January, 1935. Source: Collection van Cleemputte.Hr. Ms. K XVII during the Second World War

After war was declared to Germany on May 10th, 1940, the Dutch submarines in the Dutch East Indies were first of all utilized to safeguard the archipelago against German and Italian auxiliary cruisers. These merchant ships reconstructed to become warships had already sunk or captured several allied merchant ships and oil tankers. On 12 September, the Commander of the Navy, Vice Admiral Hellfrich decided that some Dutch merchant ships were to be shadowed by subs in order to lure a German raider into an ambush and to torpedo it. For this task Division Submarines I was appointed to which Hr. Ms. K XVII belonged with her commander Lieutenant Commander A.H. Deketh as well as O 16.

On 15 September K XVII departed from Tandjong Priok, the harbor of Batavia. The submarine escorted the Dutch steamship Lematang which left for Durban, South Africa. The O 16 left the same day from Tandjoing Priok with the tanker Olivia which left in the direction of Laurenҫo Marques in Mozambique. The Dutch submarines did not succeed in trapping a German raider and within a few days the method to use a merchant ship as bait was abandoned. But the escort services were continued and already by the end of September K XVII was on her way to accompany SS Salando, which had left from Durban, from Sunda Strait to the Indian Ocean.

In March 1941 K XVII, together with K IX and K X was sent to Sunda Strait as the German pocket battleship Admiral Scheer was sighted in the Indian Ocean. The enemy ship was raiding allied merchant ships and seemed to be on her way to Sumatra. The submarines K XIV, K XV and K XVII carried out patrols near Sabang, at the north end of the large island. De Admiral Scheer however did not try to enter into East Indian waters and the subs could resume their normal patrol tasks. On April 3, 1941 Lieutenant Commander A.J. Bussemaker took over command of Hr. Ms. K XVII.

From April 1941 the threat of a Japanese invasion was judged to be greater than the risks run by the German raiders and the priorities were adjusted accordingly. The most important task from this moment on was to shadow Japanese transports to ensure that those were not heading for Dutch East India. In June K XVII, K XVIII and O 16 were directed towards the north-west of the archipelago as a Japanese transport fleet had been spotted. Upon arrival in the indicated area, immediately patrol actions commenced. Early July K XVII and O 16 were recalled to Surabaya for maintenance. Their tasks were taken over by other Dutch subs. On 20 September, 1941, Lieutenant Commander H.C. Beҫanson took command of Hr. Ms. K XVII.

Definitielijst

- battleship

- Heavily armoured warship with very heavy artillery.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

Images

The downing of Hr. Ms. K XVII and Hr. Ms. O 16 according to official sources

When the Netherlands declared war on Japan, a few hours after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December, 1941, 15 Dutch submarines found themselves in the waters of the Far East. These boats were, as far as they were operational, divided into four divisions. Submarine Division I consisted of K XVII and O 16 and had been put under the command of the British Commander in Chief, China, who ordered both ships to Singapore. From there they were directed by Admiral Layton towards the South Chinese Sea in order to patrol off the south-east coast of Thailand.

In the evening of 12 December, 1941, Hr. Ms. O 16 under the command of Lieutenant Commander A.J. Bussemaker, sighted a Japanese merchant vessel heading for Pattani at the uttermost south-east coast of Thailand. The Dutch sub followed the enemy ship till the mouth of the Pattani river. Here the Japanese ship anchored near three other ships. The O 16 approached stealthily, sailing electrically at the surface and fired torpedoes at all four targets. The attack was successful as all four vessels sank in the shallow waters.

After this successful action O 16 headed back for Singapore. This war patrol of the O 16 would become her last as in the night of 14 to 15 December, the Dutch submarine was, sailing on the surface, hit by a heavy explosion. The submarine sank within a minute and took 36 crew with her into the depth. The six men that found themselves in the coming tower or on deck ended up in the sea. Of these six castaways only Quartermaster C. de Wolf survived. After a severe survival trip of 35 hours he reached swimming the isle of Pulau Dyang where he was received and treated by the local population. On December 21st he could report to Singapore and deliver his account.

It was assumed that OI 16 had hit a mine. It was known that there was British mine field south of Pulau Tioman. Because of the bad weather of 14 December the O 16 could have been diverted from her course ending up in the minefield. Also she could have been hit by a British mine adrift. A third possibility was that she had hit a Japanese mine. In the area Japanese mines had been laid of which fact at that moment O 16 could not have been aware. With the downing of the O 16, 41 crewmembers lost their lives among whom the very capable Commander Bussemaker.

On 14 December, the K XVII on patrol met K XII on her way to Singapore. By Aldis lamp K XVII was informed to look out for a Japanese submarine which was supposed to be nearby. This was the last time K XVII was sighted. Up to and including 21 December regular radio contact has taken place between Dutch and British naval commanders and the Dutch submarine. Thereafter nothing has been heard any more from K XVII.

As K XVII has been in the same area where O 16 found her destiny, up till and including 21 December, it has been assumed that also this submarine had fallen victim to a British or Japanese mine. It is however not unthinkable that one of both subs has been hit by a Japanese torpedo from a Japanese submarine. Around 7 December 10 Japanese submarines of submarine flotillas 4 and 5 were posted in three reconnaissance lines of which the moist southerly, with three boats, was situated approximately at the latitude of Kuantan at the east coast of the main land of Malaysia. This largely overlapped the area where the Dutch Submarine Divisions I and II were active.

Japanese data reported rather large activities of their destroyers and mine sweepers along the east coast of Malaysia during the days K XVII was present there. They mentioned among others attacks with depth charges at an enemy sub on 18, 22 and 23 December, but without certain results. So also the possibility of a sinking caused by Japanese depth charges cannot be excluded.

On 26 December the Dutch sub was so much delayed that the British naval authority announced that the vessel had to be considered to be lost. At the wrecking of Hr. Ms. K XVII all 36 crew lost their lives amongst whom commander Lieutenant Commander H.C. Beҫanson.

Definitielijst

- mine

- An object filled with explosives, equipped with detonator which is activated by either remote control or by colliding with the targeted object. Mines are intended to destroy of damage vehicles, aircrafts or vessels, or to injure, kill or otherwise putting staff out of action. It is also possible to deny enemy access of a specific area by laying mines.

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

Images

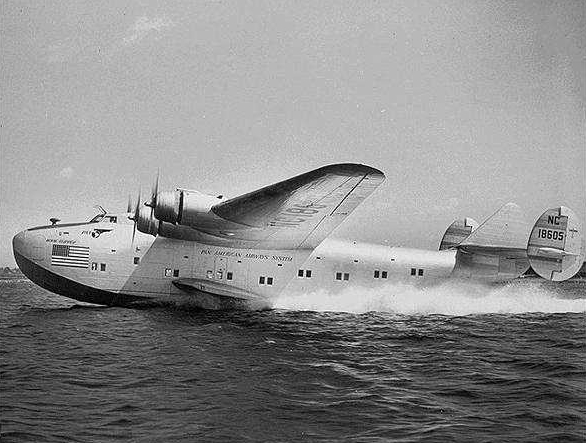

Hr. Ms. O 16. Source: Wikipedia.

Hr. Ms. O 16. Source: Wikipedia.The foundering of Hr. Ms. K XVII according to Christopher Creighton

In 1996 the book “Operation JB. The last great secret of WWII” by Christopher Creighton was published; the author was a former secret agent of the British Secret Service. The book relates the kidnapping of Hitler’s secretary, Martin Bormann in 1945 by a secret British commando, called Section M. The target of the operation was Bormann’s access to the enormous banking assets of the Nazi party. The overall leadership of the operation was in hands of Ian Fleming and the operational command was trusted to Christopher Creighton who was only twenty years of age at that time.

In the book also the Dutch submarine K XVII was mentioned, which was supposedly blown up on December 7, 1941, by Creighton. In a discussion with Fleming, in chapter 9, memories of the submarine are being recollected and in an appendix the author details the matter.

The decision to destroy the submarine was taken when that vessel discovered the Japanese fleet on its way to Pearl Harbor on 28 November 1941. The Dutch commander Lieutenant Commander H.C. Beҫanson, immediately sent a coded message to the British admiralty. This message was intercepted by the cryptologists of Section M who sent it onwards to General Donovan in Washington DC and to Major Desmond Morton of the American and British secret services. Both of them informed their leaders, President Roosevelt and Winston Churchill.

These four people were informed about the forthcoming Japanese attack, which had to remain strictly secret. In those days approximately 80 percent of the American population was extremely isolationist orientated and strongly opposed against war with Germany or Japan. Roosevelt though wanted a war with Japan but could not declare war without a valid reason. The surprise attack on Pearl Harbor would provide him this reason. The argument for America to get involved in the war was that otherwise Japan would have their hands free to occupy countries like India, Australia, New Zealand and countless other countries around the Pacific and Indian Ocean. These countries were the most important sources for raw materials for the USA and would be very difficult to liberate later on. Furthermore the British needed the support of the Americans very badly in their battle with Germany.

As on Hawaii there were a large number of immigrated Japanese, of whom a part was active as a spy for their country of origin, the naval base of Oahu could not be alarmed. The attack had to remain a secret. If that would not be the case, Emperor Hirohito, who insisted that the attack needed to be a complete surprise, would have cancelled the attack. If it would become known that Roosevelt and Churchill had been aware of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and had not acted accordingly, they would have been politically exterminated. Apart from that, the allied intelligence services were convinced that in such case the allied companionship would disintegrate whereby Japan but also Germany would have their hands free. That is why it was decided that the crew of Hr. Ms. K XVII had to be silenced.

As soon as the message of the submarine had been sent, they received the order to return to Singapore. K XVII was not enter into any harbor and the crew had to abstain from any further messaging about the Japanese fleet. Under the cover name of Lieutenant Paul Hammond Creighton travelled with a Berwick flying boat via Nova Scotia, Canada, San Francisco and the isle of Wake to the North Marianas. There he boarded K VII as agreed. Creighton had been given powers of attorney by the British Submarine Services, Admiral M. Horton, the Dutch Naval Authority in London, Admiral Fürstner and Queen Wilhelmina. These powers provided him with the authority to issue operational orders to commander Beҫanson as the Dutch sub was placed under British operational command.

Near one of the smaller Marianas, just south of Pagan and approximately 800 nautical miles south of Japan the Berwick flying boat unloaded crates into the submarine. The Dutch crew was told that the crates contained Christmas gifts from their colleagues in Great Britain. Most of the crates indeed contained gin, beer, champaign and other Christmas things. But inside one crate there was cyanide gas and in two others there were igniters, explosives and time switches. Creighton waited for a coded radio message. In case the Japanese fleet would cancel the attack on Pearl Harbor, his operation would be suspended.

The next day, Sunday December 7th, 1941, the British secret agent received the order to continue the operation. That night he left the K XVII and returned to the Berwick. Half an hour later the deadly cyanide gas escaped and it could be seen how the crew tried to escape from the sub. A little bit later the vessel exploded and sank. Creighton made sure that there were no survivors.

Definitielijst

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

Images

The mystery unraveled

Christopher Creighton had already once before provided his cooperation with a publication, a book called “The Paladin” , in which he demolished a Dutch submarine, but thousands of miles further to the south-east, near the Fiji islands. Disguised he appeared on Dutch television. The reporter connected the assault to the missing K XVII by presenting this possibility suggestively to Creighton. This fact and the fact that not a single post-war report about the British secret services mentions a Major Desmond Morton and Section M(orton) make the statements by Creighton at least doubtful. Furthermore it does not sound very credible if someone states to have been incorporated with an ultra-secret unit when he is only fifteen years of age and succeeds in blowing up a submarine with 36 crew when he is barely 16. Apart from that Hr. Ms. K XVII would have had to be north of Japan in order to have been able to discover the Japanese Pearl Harbor fleet. Namely this fleet had departed from Etorofu the most southerly island of the Kurilles on 26 November, 1941. This was thousands of miles away from the sub’s indicated operational area.

The proof that Creighton’s version cannot be the truth is the meeting between K XVII and K XII on December 14th 1941. This encounter was confirmed in 1953 by the commander of the K XII, Lieutenant Commander H.J.C. Coumou in a letter to the Head of Naval History of the naval staff. Also the radio communications K XVII has had with the allied naval staff up till and including 21 December contradict Creighton. The former secret agent however discount these messages as deliberate falsified radio messages.

The findings of Creighton in the book “The Paladin” and his masked appearance on Dutch TV made the son of commander Beҫanson, H.C. Beҫanson jr. (himself a retired naval officer) decide to unravel the secret around the fate of K XVII and his father. The Royal Navy was not very interested and decided not to spend any money or time on the research. Through the Office for Maritime History (Bureau Maritieme Historie) of the Royal Dutch Navy, presently the ‘Dutch Institute for Military History’ in The Hague, he got into contact with an Australian diver, Michael Hatcher, who had discovered a wreck of a supposedly Dutch submarine, in the South Chinese Sea close to the island Tioman.

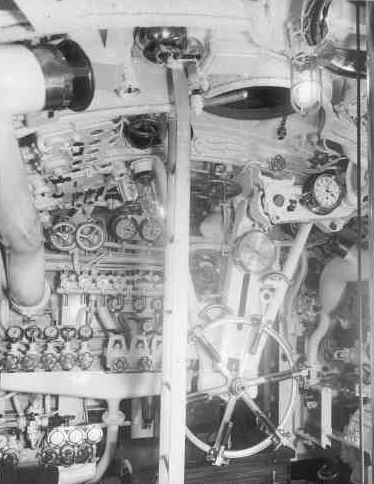

Beҫanson jr. contacted Hatcher and in May 1982 they guided a diving expedition to the wreck. The divers reported that the wreck had sunk deep in mud which made her number on the bow undecipherable. The number on the coming tower was also not readable because of coral growth. The divers however had been able to detach the bronze steering wheel from the submarine. The serial number of the wheel was compared with the data of the navy and the wreck was positively identified as Hr. Ms. K XVII. Furthermore the divers reported that there was a hole in the bow of the sub which indicated a collision with a mine and certainly not an explosion from within the ship.

Leaving one question. The wreck was situated almost twenty nautical miles from the spot where the Japanese mine layers were supposed to have laid their mines. In 1991 this last piece of the jigsaw puzzle was put in its place during a meeting of Beҫanson jr. with the Japanese naval officer N. Kitazawa. He pointed the attention of Beҫanson jr. towards the book “The day Imperial General Headquarters trembled for fear” from 1968. In this book it is being described that the Japanese laid mines within one kilometer from the place where K XVII has been found. Actually these mines would have to be laid 30 kilometer further south but the Japanese merchant ship, reconstructed into an auxiliary minelayer, Tatsumiya Maru was discovered on 6 December by a Dutch flying boat which caused her to turn around. But first she laid her mines whereby the minefield ended up many nautical miles away from the targeted place.

Beҫanson ‘s research had generated quite a lot of publicity which in its turn caused the report by the Swedish diver Sten Sjöstrand in 1995, that he had discovered another wreck of a supposedly Dutch submarine, to receive much attention from the Royal Dutch Navy. The wreck found itself within 10 nautical miles from that of the K XVII in the same line of Japanese mines from the Tatsumiya Maru . Stimulated by family members of the crew of Hr. Ms. O 16 the navy organized an expedition to the recently discovered wreck. Among the members of the expedition were H.C. Beҫanson jr. as well as H.O. and A.P. Bussemaker, both sons of commander Bussemaker and also retired naval officers. The wreckage which showed a big hole in the skin just in front of the tower, became positively identified as being O 16. Also this time the steering wheel as well as some other recognizable parts were salvaged in order to confirm the identification.

Faced with these findings Christopher Creighton came in 1996 with new facts in an interview with a national newspaper, which had to support his version of the foundering of Hr. Ms. K XVII. Shortly after the war American, British and Dutch authorities would have agreed that the assault on K XVII had to be kept secret. Therefore a Dutch submarine which looked much alike the K XVII and which was destined to be scrapped, was equipped with a steering wheel with the serial number of that of K XVII, having been scuttled at the spot where the wreck had been found. Therefore mines were supposed to have been dismantled and replaced. But no one involved could have been aware so shortly after the war of the Japanese data regarding the diverging places where the Tatsumiya Maru had floated her explosives.

Furthermore Creighton indicated that all documents regarding the K XVII had been destroyed or falsified by the British Secret Service. The Dutch Institute for Military History however is in possession of the safeguarded salary administration from Surabaya. From that administration it becomes clear that Hr. Ms. K XVII left Surabaya on 28 November 1941. The submarine therefore could never have discovered on that day a Japanese fleet on its way to Pearl Harbor.

Definitielijst

- mine

- An object filled with explosives, equipped with detonator which is activated by either remote control or by colliding with the targeted object. Mines are intended to destroy of damage vehicles, aircrafts or vessels, or to injure, kill or otherwise putting staff out of action. It is also possible to deny enemy access of a specific area by laying mines.

- ultra

- British intelligence service during World War 2

Images

The end

The way in which Creighton describes the supposed sabotage of the K XVII and his connections with Ian Fleming make one think of a series of popular action movies. The letters JB of the title of his book mean James Bond. The author seems to provide his own fantastic filling in of unexplained moments of history. There is nothing wrong with that if the stories are being presented to be fictitious. Creighton however hard headedly states that everything happened as he describes it.

But the perseverance of Creighton has also caused motivated people to stand up and find proof That K XVII and O 16 have fallen victim to an unknown Japanese minefield. If the former secret agent had not raised such turmoil about his thriller, probably the right people had not been motivated to discover the truth. The disappearance of K XVII and O 16 would probably have remained an unsolved mystery.

Also the crews of both disappeared vessels cannot be blamed. They were not diverging from their heading and have not ended up in a British minefield by accident. Apart from that, they have not been surprised by an enemy submarine or destroyer. They only were at the wrong time at the wrong place.

Definitielijst

- destroyer

- Very light, fast and agile warship, intended to destroy large enemy ships by surprise attack and eliminating them by using torpedoes.

Information

- Article by:

- Peter Kimenai

- Translated by:

- Fred Bolle

- Published on:

- 03-02-2013

- Last edit on:

- 30-09-2024

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related books

Sources

- BEZEMER, K.W.L., Zij vochten op de zeven zeeën, Uitgeversmaatschappij W. De Haan N.V., Zeist, 1964.

- BOSSCHER, PH., M., De Koninklijke Marine in de Tweede Wereldoorlog deel 2, Uitgeverij T. Wever B.V., Franeker, 1986.

- CREIGHTON, C., Operatie JB, Balans, 1996.

- MARK, C., Schepen van de Koninklijke Marine in W.O. II, De Alk bv, Alkmaar, 1997.

- MüNCHING, L.L. VON, Schepen van de Koninklijke Marine in de 2e wereldoorlog, De Alk bv, Alkmaar, 1978.