Introduction

In 1923 Baron Van Palland donated his 18th century castle en 2000 hectare woodland belonging to his estate Eerde, in the proximity of Ommen, Province of Overijssel, to the British Indian Jiddu Krishnamurti. This man was the head of the order of the Star, a theosophical movement. During the summer of 1924 the first Star camp gathered in the woods of this estate. In the following years small wooden houses and large wooden barracks were built in this hilly area the Besthemerberg, to house administration, kitchen, warehouses, lavatories and washrooms. Krishnamurti left, but the meetings continued until 1939. In 1940 the meeting was postponed because of the threat of war.

At the end of 1940 the camp was not liquidated, as was usual with unwanted organisations, but transferred in its entirety to the head of the executive body Referat Internationale organisationen, (Unit international organisations), Werner Schwier, a horse butcher from Germany, born in 1907, who falsely liked to grace himself with the title of Doctor, also held other jobs within the NSDAP, such as Gauredner and Bereitschaftsführer der Ordensburger (function within a training program for the party framework). The Star camp would yet prove its use, at least in the eyes of Schwier.

Images

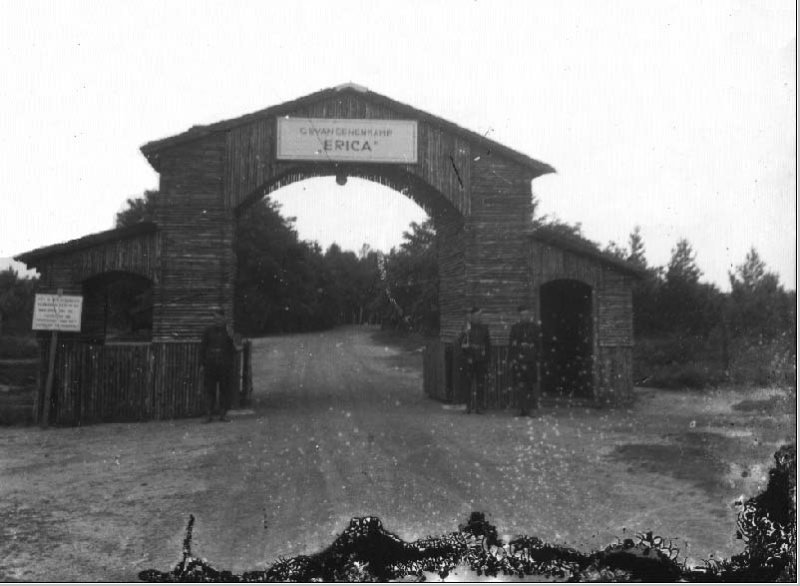

Gate ‘A’ of the outer ring. The transfer of the prisoners took place here Source: Historische Kring Ommen.

Gate ‘A’ of the outer ring. The transfer of the prisoners took place here Source: Historische Kring Ommen. Plan of camp Erika. Source: Historische Kring Ommen.

Plan of camp Erika. Source: Historische Kring Ommen.Construction and opening of camp Erica

Schwier hired Karel Lodewijk Diepgrond, a former police officer and NSB member (NSB: the National Socialistic Movement in the Netherlands). This man was at the time an interpreter with the SD (Sicherheitsdienst: Nazi security service). He was charged with the task of recruiting staff. On the arrival of Diepgrond and 48 guards, the establishment of the camp was started on June 13, 1941. A larger part of these guards consisted of Amsterdam unemployed. The men were told that they were going to manage a Dutch camp for "antisocial" Jews. Nonetheless, German ranks were introduced: Diepgrond was made "Lagerführer" (camp leader), a German name was chosen for the watch team, KK (Kontroll Kommando) and a German name for the camp: ‘Arbeitseinsatzlager (labourcamp) Erika’. The destination would be either a training camp for a "colony" in the Ukraine or a ‘Jewish camp’. For the latter destination were two options: a ‘Durchgangslager’ (transitcamp) or an ‘Arbeitslager’ (camp for forced labour).

Although the destination had still to be confirmed, the setting-up of the barracks was started. Trees were felled and fencing installed. Furthermore, there was drill, led by a Dutch SS’er and two former marines, one of them a Lieutenant Jan de Jong, who eventually was given the German rank of Hauptzugführer (platoon leader). The uniforms were from the Dutch army, trimmed with buttons ordered by the SS, collar badges containing KK, field caps with skull and a black band on the left sleeve with KK stitched thereon. From July 20, 1941 there were exercises on the shooting range. An expansion of the number of guards with 22 men followed, again recruited by the NAF (Dutch Labour Front). This second group contained the first Dutch SS men, later followed by more, until finally 110 guards, from different backgrounds were active.

The first prisoners were 15 NSB members (Dutch Nazi faction), sent there by Beauftragter (representative) Völckers for ‘re-education’. The reason for this was their raid on the mayor of Rotterdam, Mr. Oud, due to the expulsion of an NSB town councillor. Mr. Oud was forced to pose for a picture in an imitation Masonic apron, bearing a Star of David. After the initial rough treatment by the guards there was great freedom of movement for the prisoners. So much so that three of the Rotterdam prisoners remained in the camp to join the Kontroll Kommando (control command). The long vacancy period and the uncertainty about the existence of the camp led to an exodus of KK. So were 38 guards approved for service in the Waffen-SS (military branch of the SS) and left to Durchgangslager (transit camp) Amersfoort, were they performed guard duties as well.

In March 1942 the plan for Erica was clearly outlined: it was designated as a camp for prisoners of the Dutch judiciary and, in particular, economic offenders (ration coupon fraudsters, illegal butchers, black marketeers, etc.). By order of Arthur Seyss-Inquart (highest person of authority in the occupied Netherlands) Erika became a "Justizlager" (Justice camp), where prisoners were forced to hard physical labour. The depleted KK was again supplemented, this time also with a number of men from the NSB-department Assen. It was also decided that future prisoners would be employed in Germany.

The first prisoners arrived on June 19th, 1942. At that moment there was a capacity for 800 'offenders' and an expansion to 1300 inmates was being worked on. On July 1st 1942, there were 368 prisoners in Erika and on August 1st of the same year the number had risen to 1380. Meanwhile, there were, besides economic offenders, also offenders with more serious crimes included in the camp, at least 4 people who were convicted under Regulation 81/40: the prohibition of all homosexual acts. Furthermore, there were at least eight Jewish people incarcerated, three of which not judicially.

Due to the ever-increasing pressure to house more 'offenders', expansion of capacity was created to accommodate 1500 prisoners. A further 500 were employed in Germany. On November 30, 1942, 2013 prisoners and 251 guards were housed in Erika, together with its branches in Junne (three kilometres further on) and, among others, Heete, Wesseling and Cologne in Germany (the guards went along).

Definitielijst

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- NSB

- National Socialist Movement. Dutch political party sympathising with the Nazis.

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

- Waffen-SS

- Name of Military section of the SS.

Images

Mayor Nering Bögel addresses the NAD Source: Historische Kring Ommen.

Mayor Nering Bögel addresses the NAD Source: Historische Kring Ommen. A party of prisoners with guard photographed with the farm where they worked (1943) the uniform is clearly visible. Source: Historische Kring Ommen.

A party of prisoners with guard photographed with the farm where they worked (1943) the uniform is clearly visible. Source: Historische Kring Ommen. A guard with a party of prisoners (presumably in the neighbourhood of Junne). Source: Historische Kring Ommen.

A guard with a party of prisoners (presumably in the neighbourhood of Junne). Source: Historische Kring Ommen. Prisoners marching back to "Kamp Erika", through the "Bouwstraat"in Ommen (1943). Source: Historische Kring Ommen.

Prisoners marching back to "Kamp Erika", through the "Bouwstraat"in Ommen (1943). Source: Historische Kring Ommen.Life and ill-treatment in Justitzlager Erika

The prisoners arrived at the Ommen railway station under surveillance by the Marechaussee (Dutch police), they had to march three kilometres to the gate where they were handed over to the guards. There, a dark period started for the prisoners of Justizlager Erika. There was abuse, shouting and beatings, and anybody who dared to say anything was beaten bloody. Then the prisoners were recorded and the 'knackers' (lice, unworthy, parasites) had to stand to attention for hours on end. If they did not adhere to that, they were introduced with a popular punishment, to 'seal'. The prisoner had to move over the ground with his elbows, a long body, chin and toes stretched. If they failed to do that to the satisfaction of the guards, more beatings followed.

Constant harassments, beatings and intimidation were daily practice, even so when eating. Piping hot soup or mashed potatoes had to be eaten between the first, and second whistle, while there was never more than five minutes between whistle signals. Abstinence or halving of rations was also a common punishment, so were to the ‘wire stand’ and ‘gramophone record rotation’. ‘To stand at the wire’ was a punishment to maintain social control within a team at high level. If a prisoner made a mistake, then the whole team had to stand in line, one behind the other, with one hand on the barbed wire. This lasted as long as the guard thought necessary. A more individual punishment was the aforementioned 'turning picture'. The prisoner had to push the index finger of his left hand in his ear and the index finger of his right hand, bent, on the ground and in that position go in circles around his own axis. When the prisoner fell down by vertigo, he was beaten up again, often till he went down unconscious.

When food was found in the clothing of the prisoner, it was beaten into his mouth on the parade ground. Also, public beatings were rife which were intended as a humiliation. Often a so-called ‘pillory’ was used, to which ‘offenders’ were chained. Then there was the ‘bunker’: a concrete hole in the ground, too low to stand upright in, as a heavy hatch, with long nails driven through it, shut off the hole. The bottom of the bunker was always covered with water, containing faeces and urine. Regularly, prisoners stood or sat in there for days on end, usually without food and for minor infractions, such as unauthorised talking. Many emerged from this situation traumatised and with a severe pneumonia.

Then there was the SK, or Straf Kompanie (punishment squad) consisting of an average of ten to twenty prisoners and those were even more systematically mistreated. These prisoners were beaten and kicked, particularly in the genitals, which often swelled considerably in such a way that some of them died, owing to internal bleedings. They were beaten up with clubs and rifle butts, with such violence that they sometimes broke off. The Jews who were imprisoned in Erika underwent the same treatment. They were housed separately in a tent on the grounds of the camp. At night, the Jews had to hand in their clothes to sleep naked in the cold.

The concentration camp system of Lagerpolizei (camp police, also called Kapo), introduced by the camp management whereby prisoners were employed as guard (Kapo, Erika ‘Kaputt’ (smashed) called by the prisoners), led to horrific abuses. These Kapo’s were no second in cruelty to the guards. Oberkapo Rien de Rijke in particular "excelled" in atrocities. In several cases it was simply brutal murder that took place at the many deaths in Erika. The situation at the branches in Germany the daily reality was no different. The guards applied the same methods of practice gained in Erika. The situation in Heerte (vicinity of Brunswick) in particular, was so terrible that the prisoners, guards included, returned sooner at the command of Schwier. In Heerte they were billeted at the Hermann Göringwerke, camp 35, where previously Soviet POW’s had been housed. A great number of prisoners perished, due to the frustations of the guards about their own living conditions. Guards and prisoners were led by Halbzugführer (deputy platoon leader) Driehuis.

Definitielijst

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Kapo

- A Kapo was a prisoner in a concentration camp in Nazi Germany during World War 2 who was assigned to supervise other prisoners. A Kapo had to supervise the work of the prisoners and was responsible for their results on behalf of the SS.

- POW

- Prisoner of War.

Images

Photo, taken by a resident of Ommen, from prisoners on their way to work with farmers in the area. The caption reads: 'Links, zwei, drei, Source: Historische Kring Ommen.

Photo, taken by a resident of Ommen, from prisoners on their way to work with farmers in the area. The caption reads: 'Links, zwei, drei, Source: Historische Kring Ommen. Ober-Kapo (head guard) Rien de Rijke with a (Jewish) prisoner. Source: Historische Kring Ommen.

Ober-Kapo (head guard) Rien de Rijke with a (Jewish) prisoner. Source: Historische Kring Ommen. A cudgel used by an Erika guard. Source: Historische Kring Ommen.

A cudgel used by an Erika guard. Source: Historische Kring Ommen.End of Justitzlager Erika

Due to the many maltreatments and deaths, the illegal newspaper ‘Het Parool’ devoted in September 1942 an article on the abuses in Erika. It called for action by the judiciary. For the judiciary, however, this was not enough. They wanted proof. In January 1943 four judges, dressed as doctors, visited thirty patients from Camp Erika in the hospital in Hengelo. This visit made a deep impression on the judges. From that moment on, action was taken by the judiciary, with a first report on the situation as it was found in Hengelo. Eventually, a letter was drafted, signed by the judiciary of Amsterdam, threatening to terminate cooperation with the sentencing of suspects if they had a chance to end up in Erika. This resulted in the order of Arthur Seyss-Inquart that all the condemned by the Dutch judiciary had to leave the camp before May 31, 1943. Schwier protested against this and did not cooperate, but at the end of 1943 the last prisoners were transferred.

In the period from June 1942 to May 1943, between 170 and 200 of the 2978 prisoners in Erika and its annexes were killed. After this period, the camp got a new capacity: a camp for "anti-socials" and refusers of the Arbeitseinsatz (employment in German service).

Definitielijst

- Arbeitseinsatz

- “Labour deployment”. Forced deployment in the German industry. Approximately 11 million European citizens were rounded up and deployed into forced labour in the Third Reich. Not to be confused with the Arbeidsdienst or labour service, an organisation for national-socialist education for Dutch youngsters.

"Camp for forced labour" and "transit camp" Erica

The first temporary residents of the renamed camp were students who responded to the summons for the Arbeitseinsatz and stayed there for a couple of weeks under good conditions. They stayed here in transit on their way to the labour locations in Germany. Due to the slow influx of new prisoners, a new job was found for 74 man of the KK: they were employed in the detection of people who tried to dodge the employment in the Arbeitseinsatz. Generally, these guards were members of the NSB and the SS, the military uniform and rifle were exchanged for a black uniform and a pistol. In this capacity, they also took part in raids. The number of prisoners who were locked up in Erika and transmitted to Amersfoort as a result of these actions in the period between May 1943 and September 1944 cannot be given with certainty, but must have been somewhere between 2500 and 3000. The number of "anti social" prisoners averaged presumably around 500 prisoners.

The treatment of the prisoners in Arbeitseinsatzlager (employment camp) Erika was generally better than that of the previous period. There was a marked difference in the treatment of the Arbeitseinsatz-prisoners and de so-called anti-socials. The former were decidedly less lucky. There was less abuse, but punishments like "gramophone record rotation" and "the bunker" were maintained, together with the Straf Kompanie (punishment squad). Somewhat more time was given for the food, but the quality was still poor. Some prisoners died but no longer in large numbers as in the days of the Justizlager.

Lagerführer (camp leader) Diepgrond was arrested himself by the SD on February 1944, due to the release of a number of "anti socials", but was released the following day through the interference of Schwier. In April 1944 Schwier entered into the service of the staff of the General Kommissar für das Sicherheitswesen und Höhere SS und Polizeiführer Hans Rauter (General commissioner for security and higher SS police leader Hans Rauter) and was given command of the newly established Arbeitskontrolldienst (AKD) (Labour inspection service). The men of the KK were transferred to this new service and the Polizei Freiwilliger Bataillon Niederlande (police volunteer battalion Netherlands) or they resigned.

Definitielijst

- Arbeitseinsatz

- “Labour deployment”. Forced deployment in the German industry. Approximately 11 million European citizens were rounded up and deployed into forced labour in the Third Reich. Not to be confused with the Arbeidsdienst or labour service, an organisation for national-socialist education for Dutch youngsters.

- NSB

- National Socialist Movement. Dutch political party sympathising with the Nazis.

Images

Lagerfüher Karel Lodewijk Diepgrond adresses students, who wentto Germany. Source: Historische Kring Ommen.

Lagerfüher Karel Lodewijk Diepgrond adresses students, who wentto Germany. Source: Historische Kring Ommen.Penal establishment Erika

From this AKD (Labour Inspection Service) a group of 35 to 40 men were selected in September, who fell under the German Ordnungspolizei (order police) with the name Wachgruppe (guard team) Ommen. This group was responsible for camp Erika and wore the green uniforms of the infamous ‘Grüne Polizei’, (German Military Police). Furthermore, new ranks were introduced. Owing to the fact that they now fell under the Ordnungspolizei, the camp was no longer a ‘Durchgang- und Arbeitslager’, (transit- and labour camp) but a prison camp. The prisoners, around 450 persons, consisted of Arbeitseinsatz dodgers, those suspected of illegal activities and violators of the distribution laws. The penalty of these prisoners was completely randomly determined.

Members of de SD (security Service) stayed regularly in Erika. Together with members of Wachgruppe (guard team) Ommen, so-called strong-arm squads were formed. They consisted of around 15 selected guards en SD people. Day and night these "strong-arm squads" were looking for offenders and people in hiding in the surrounding area of Erika. Violence and intimidation were not avoided. Of those arrested, valuables or useful household goods were confiscated, the rest was destroyed. Houses were also set on fire. Those arrested were almost always severely mistreated, during interrogation or on their way to Erika.

The main participants in these raids came from the officer frame Schwier, Diepgrond and de Jong. From the original Kontroll Kommando: Jaap de Jonge, Freek Kermer, Toon Soetebier and Herbertus Bikker. The latter acquired the nickname "the butcher of Ommen. At least 10 deaths are known in the last 4 months of 1944 as a result of executions by members of this strong-arm squad.

From the end of December 1944 the treatment of the prisoners by the guards improved slightly, although excesses still occurred. There was another dead during this last period, due to an execution. A further three dead and 29 wounded were due to an allied air raid on January 14, 1945.

From February 1945 on, less and less guards returned from leave or simply deserted. From march 22, 1945 Schwier had them locked up in the sleeping barracks to prevent them from leaving.

In the early hours of April 5, 1945 approximately 450 prisoners were dragged from their beds and marched off. With about 300 prisoners the guards arrived in Hoogeveen. The next morning the march was continued in the direction of Westerbork. Another 113 less arrived there than at departure from Westerbork. Many had made use of the opportunity to flee during various air raid attacks underway. In camp Westerbork, on the 10th of April 1945, they were eventually liberated, by the first Polish armoured division and the Prince Bernard brigade of the Netherlands interior forces.

Definitielijst

- Arbeitseinsatz

- “Labour deployment”. Forced deployment in the German industry. Approximately 11 million European citizens were rounded up and deployed into forced labour in the Third Reich. Not to be confused with the Arbeidsdienst or labour service, an organisation for national-socialist education for Dutch youngsters.

- brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- Grüne Polizei

- Green Police, nickname – due to their green uniforms – for the Ordnungspolizei (Order Policy) and which is the common denominator for local policy units tasked with exercising regular policy responsibilities during Nazi-Germany from 1936 to 1945.

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

Images

Entrance to the camp. Source: Historische Kring Ommen.

Entrance to the camp. Source: Historische Kring Ommen. Entrance to the so-called "Palissadenkamp". Source: Historische Kring Ommen.

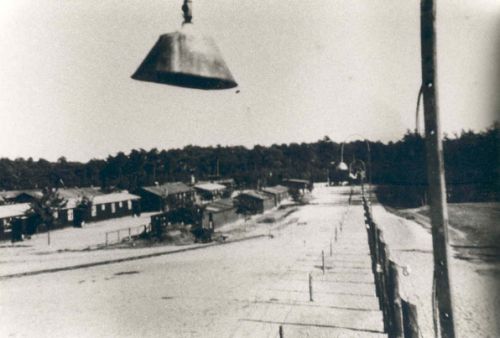

Entrance to the so-called "Palissadenkamp". Source: Historische Kring Ommen. View from the watchtower into the "palissadenkamp". Source: Historische Kring Ommen.

View from the watchtower into the "palissadenkamp". Source: Historische Kring Ommen.After the Second World war

Immediately after the liberation on April 11, 1945, Prison camp Erika was given another position and name: Detention camp Erika. In this capacity it remained in function until December 31, 1946. Among others, Lagerführer Diepgrond, Bikker and other guards of Erika were detained here. During the first weeks after the liberation harassments and occasional abuse occurred but not thereafter. Erika was in comparison with other custodian and internment camps one of the few with relatively good conditions. A typhoid epidemic broke out however, which ultimately resulted in the death of 120 prisoners. Owing, among other things, to inaccurate estimates and too few opportunities to fight the typhoid it took a year to get the epidemic under control.

After the camp and the surrounding grounds was given back to its former owner, Baron Van Pallandt, he granted the area on March 3, 1948 to the Foundation Eerde, who, in turn, sold it to the Foundation Besthemerberg. This foundation gave the land in lease to the Foundation ´Vacantievreugd´ Holiday´s Joy. At the moment, one of the largest camping sites of Ommen is located here, where until recently holidaymakers stayed in the cabins of the officers. All that remains now is a simple monument in the form of a wooden cross, a stone a small information board and a bench.

Afterword

Erika is not a well known camp and some people claim that what happened here is of less importance because it was thought that, above all, the offenders were sentenced by the Dutch courts and subsequently imprisoned and that they were no victims of persecution by the German occupiers. Fact is however that these convicts were sentenced under impure Dutch law and under the responsibility of the German occupiers. This happened at a time when Jews and people in hiding were condemned as criminals and human rights were trampled. Until September 1942, Dutch judges had no idea to what places the convicted men were sent. Furthermore, not merely offenders of Dutch law were dealt with, but also Jews and people in hiding, suspects of illegal activities, dodgers of the Arbeitseinsatz (forced employment in Germany), and the so-called ´anti-socials were brought to this camp without any form of trial.

One of the prisoners who also experienced the notorious camps in Poland and Germany declared about Erika: "In no other camp I was so systematically physically mistreated, "that is to say, every day, as in Ommen". A great many men have suffered terribly and died needlessly because of their sadistic guards. Killed by beatings, executions, poor living conditions, malnutrition and heavy labour. Many of them were men who devoted their energy to the wellbeing of the victims of the German occupiers or were active in the resistance against the occupier, they were innocent or the treatment was not in proportion to the penalty imposed. A treatment that improved slightly in the last stage of the war, owing to the lost Ardennes offensive and the clearly emerging defeat of Germany.

|

Kommandant Werner Schwier has never been convicted by a Dutch court because he managed to escape to Germany after being imprisoned in a Belgian internment camp. |

|

Lagerführer Karel Diepgrond was sentenced to 20 years. He served only 8 years thereof, after this, he was granted a pardon. |

|

Hauptzugführer Jan de Jong was shot on flight in the woods near Eelde a few weeks after he escaped from Westerbork. |

|

Halbzugführer Johannes Driehuis was sentenced to death and executed in 1947. |

| Unterführer Johnny Boxmeer was sentenced to lifelong imprisonment but this sentence was commuted to 24 years minus the already served period. | |

|

SS-Sturmmann Herbertus Bikker was sentenced to death but this was commuted to life imprisonment. In 1952 Bikker succeeded to escape to Germany from the Breda prison. He was arrested by the German police, but not extradited due to his membership of the Waffen-SS, which entitled him to German citizenship. In 1993 he was tracked down by the KRO program "Reporter" and had to appear in a German court for the murder of the Dutch resistance fighter Jan Houtman. Owing to his bad health, the case was shelved. Bikker died in Germany in Nov. 2008. |

| Unterführer Jaap de Jonge was sentenced to life imprisonment, but managed to escape to Germany in 1952 from the Breda prison. He was arrested by the British occupation forces in the Ruhr and extradited tot The Netherlands. His sentence was commuted to 24 years minus the already served period. | |

| SS-offizier Toon Soetebier was sentenced by default to death. This was commuted to life imprisonment in 1949. Eventually he was arrested and imprisoned in Breda, but managed to escape to Germany in 1952. There he lived until his death on May 26, 2006. | |

|

Oberkapo Marinus (Rien) de Rijke After the war, he managed to escape the attention of the Political Investigation Department and built a life in Wedel, Germany. After lengthy investigations by M. Welling, he was put back on the list of wanted persons on January 1, 1986, and was arrested on May 18 of that year when crossing the border. He was sentenced to five years imprisonment due to the fact that it could not be proven that there were prisoners deceased, owing to his ill-treatment. |

Definitielijst

- Arbeitseinsatz

- “Labour deployment”. Forced deployment in the German industry. Approximately 11 million European citizens were rounded up and deployed into forced labour in the Third Reich. Not to be confused with the Arbeidsdienst or labour service, an organisation for national-socialist education for Dutch youngsters.

- Ardennes offensive

- Battle of the Bulge, “Von Rundstedt offensive“ or “die Wacht am Rhein“. Final large German offensive in the west from December 1944 through January 1945.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Waffen-SS

- Name of Military section of the SS.

Images

The former dwelling house of Schwier, demolished 1994. Source: Historische Kring Ommen.

The former dwelling house of Schwier, demolished 1994. Source: Historische Kring Ommen. Bodies of two executed prisoners.Unearthed after the war,according to indications of former Lagerführer Karel Lodewijk Diepgrond. Source: Historische Kring Ommen.

Bodies of two executed prisoners.Unearthed after the war,according to indications of former Lagerführer Karel Lodewijk Diepgrond. Source: Historische Kring Ommen. Presentation of the first monument and the book "Nederland Gedenk" by former "Knackers". Source: Historische Kring Ommen.

Presentation of the first monument and the book "Nederland Gedenk" by former "Knackers". Source: Historische Kring Ommen. Unveiling of the plaquette by two former prisoners of kamp Erika (2005), by Harry Woertink. Source: Historische Kring Ommen.

Unveiling of the plaquette by two former prisoners of kamp Erika (2005), by Harry Woertink. Source: Historische Kring Ommen.Information

- Article by:

- Frank Meijerink

- Translated by:

- Cor Korpel

- Published on:

- 10-01-2015

- Last edit on:

- 02-05-2020

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Sources

- E. VAN VELSEN (REDACTIE), Krishnamurti in Ommen, Zalsman Kampen BV, 2004.

- JONG, L. DE, Het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden in de Tweede Wereldoorlog, Staatsuitgeverij, Den Haag, 1972.

- SEINEN, K., Nederland gedenk, Uitgeverij Seinen, De Krim, 1946.

- STAPPENBELT, W., Ommen onder kroon en kruis, Larcom Grafische Producten, Ommen, 1995.

- VELDMAN, GUUSTA, Knackers achter prikkeldraad: Kamp Erika bij Ommen, 1941-1945, Stichting Matrijs, Utrecht, 1993.

- Oud Ommen, krantenberichten over Erika

- Diverse krantenknipsels over het proces van Rien de Rijke

- Gemeentearchief Ommen

- Verhoor Seyss-Inquart deel I