Operation Abigail Rachel

Preface

The German Air Force, the Luftwaffe, carried out a large scale bombardment on Coventry on 14 November 1940. A sizable part of the city was obliterated by more than 500 bombers. It was the biggest raid in a series of attacks on Coventry and other British cities. 568 people were killed and more than 1000 injured. Until then, the Royal Air Force had only carried out precision-bombing on industrial and military targets in an attempt to severely damage the German war machine. However, after the bombing of Coventry, Bomber Command was authorized to abandon its strategy to carry out a reprisal raid. The centre of the German town of Mannheim was bombed during the night of 16/17 December 1940. The raid was a forerunner of the strategy which the allies would later call 'area-bombing', a heavy and indiscriminate bombardment on a city.

Call for revenge

King George VI visited Coventry two days after the attack to witness the ravages and to encourage the inhabitants. A man in the crowd called out to him: "Give them what they gave to us! We can take it!" The next day a BBC reporter asked one of the citizens about his view on the German bombing of Coventry and Southampton. His answer was clear: "We're fighting gangsters, so we've got to be gangsters ourselves. We've been gentlemen too long."

The British people were calling for revenge for the Luftwaffe attacks, but initially to no avail. The Royal Air Force stuck to the strategy of precision-bombing on industrial and military targets. But Prime-Minister Winston Churchill authorized abandonment of the strategy on 1 December 1940. The War Cabinet was informed on 12 December. The cabinet gave their approval, on condition that the press would not depict the attack as a reprisal raid for the bombing of Coventry. Apart from that, the deviating strategy would only be experimental.

Target Mannheim

Bomber Command chose the southern German town of Mannheim as its target. The city was frequently bombed during the war, mainly because of the presence of the Mannheim Motorenwerke and the naval armaments factories. These were picked as the primary targets for the attack. The Operation Record Books, in which the targets of a raid were described, also suggest an ordinary operation. The bomb loads however held a special clue. The aircraft were mainly carrying incendiaries and high explosive bombs, especially designed to damage buildings (knock down walls and collapse roofs).

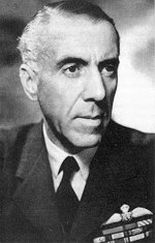

In an attempt to make the attack - codenamed Operations Abigail Rachel - successful, a force of 200 bombers was prepared. However, weather forecasts indicated thick clouds over England during the night of 16/17 December, so it was decided to cut the force to 134 aircraft. This was the largest force sent to a single target so far. The majority of the bombers were Wellingtons, of which eight were specially tasked. They led the attack and had to drop their incendiaries over the town before the main force would arrive. These Wellingons were flown by the most experienced crews. The other aircraft were to use the light of the fires as their aiming point. They had to, in the words of Air Marshal Sir Richard Peirse (the commander of Bomber Command at presence) "concentrate the maximum amount of damage in the centre of the town".

The attack

When the bombers entered German air space the weather proved to be much better than in England. It was a perfect moonlit night and clear of cloud. Visibility for the airmen was good. The leading Wellingtons dropped their incendiaries, but most of them did not fell in the city centre but in residential areas at the edge of Mannheim. This resulted in scattered bombing by the main force, as they had to use these fires as their guide. When the crews were interrogated on return at their base, they expected the raid to be a major success. More than half the crews claimed to have hit the target. The last returning crews reported that "the city centre was a mass of fires".

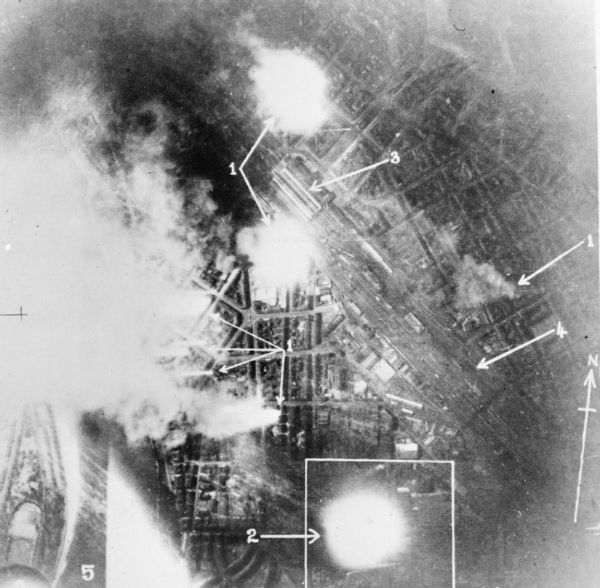

During the next two days aircraft were sent to Mannheim for photo reconnaissance. The crews reported that fires were still burning and big parts of the city were covered by smoke. However, a later evaluation of the raid showed the bombing had caused less damage than the returning crews initially claimed. The majority of the bombs had fallen far from the city centre and some had even hit the town of Ludwigshafen on the other side of the Rhine. 240 buildings were damaged or destroyed, including a school and two hospitals. One of them was a military hospital. 34 people were killed in the attack and 81 citizens were injured. It is not known if there were any fatalities in Ludwigshafen.

Defences in Mannheim were light. Regardless of the clear night no aircraft were lost over Germany, nor did the Germans shoot down any British planes over occupied Holland. Three bombers were lost on their return in England though. A Wellington IC of 99 Squadron crashed in Sussex, but the crew members were unhurt. Blenheim Z5801 of 101 Squadron ran out of fuel and wasn't able to reach RAF Station Raynham, so the crew had to bail out. Wellington P9268 of 149 Squadron overshot the runway, but this crew came out unhurt as well. A total of seven aircraft were lost and 17 airmen were killed in the raid on Mannheim.

Aftermath

After the bombardment of Mannheim, Bomber Command returned to its strategy of precision-bombing of industrial and military targets. The Command would continue with these tactics until its effectiveness was heavily criticised. Research suggested that the results of bombing operations weren’t satisfying and a lot of crews were lost. In early 1942 it was decided to appoint a new commander. Peirse was replaced by Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris. The new commander also brought a new strategy, known as ‘area-bombing’. This caused heavy bombing of a large number of German cities. Many civilians were killed in these attacks, which has been a talking point ever since. Operation Abigail Rachel had been a foretaste of this strategy.

Definitielijst

- Bomber Command

- RAF unit which controlled strategic and sometimes tactical bombing (as in Normandy)

- Luftwaffe

- German air force.

- Marshal

- Highest military rank, Army commander.

- RAF

- Royal Air Force. British air force

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

- Squadron

- A military unit in the Belgian navy usually six to eight small ships operating together under one command. The smallest military unit in the Dutch air force of about 350 men. In most countries is the designation of a military unit thesize of a company. It is either an independent unit, such as a battery, or part of a bigger Calvary unit. In the air force it is the designation of a unit of aircrafts.

- strategy

- Art of warfare, the way in which war should be conducted in general.

Images

Explosions in Mannheim, seen from an aircraft of 115 Squadron. Source: Imperial War Museum.

Explosions in Mannheim, seen from an aircraft of 115 Squadron. Source: Imperial War Museum. Air Marshal Sir Richard Peirse Source: Royal Air Force.

Air Marshal Sir Richard Peirse Source: Royal Air Force. Reconnaissance photo showing the results of the raid. Source: Royal Air Force.

Reconnaissance photo showing the results of the raid. Source: Royal Air Force.Information

- Article by:

- Pieter Schlebaum

- Published on:

- 16-05-2015

- Last edit on:

- 30-09-2024

- Feedback?

- Send it!