Preface

Arthur Harris’ name is indelibly associated with the bomber war. He led Bomber Command from February 1942 until the end of the war against Germany. During the war he was regarded as one of the greatest allied commanders, who had taken over the Command at a critical point and moved it into higher gear. But he became the target of much criticism in the last stages, especially after the bombing of Dresden. Controversies and deep differences of view still run deep, in the United Kingdom as well as abroad. Some people, especially Bomber Command veterans, think of Harris as a war hero who was badly treated by his country after the war. Others have been sharply critical about Harris carrying out the strategy of area bombing until the end of the war. When the plans for a statue in London were made public in 1991 this gave rise to a storm of protest as well as support. The Mayor of Cologne even wrote Queen Elisabeth appealing to her not to take part in the unveiling ceremony. It makes Arthur Harris no doubt one of the most controversial figures of the Second World War.

Definitielijst

- area bombing

- Aerial bombardment targeted indiscriminately at a large area. Prohibited since 1977 by the Geneva Convention. Also known as carpet bombing, obliteration bombing and moral bombing.

- Bomber Command

- RAF unit which controlled strategic and sometimes tactical bombing (as in Normandy)

- strategy

- Art of warfare, the way in which war should be conducted in general.

Images

Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Arthur Harris Source: National Portrait Gallery.

Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Arthur Harris Source: National Portrait Gallery.Early career

Arthur Travers Harris was born on 13 April 1892, at Cheltenham, Gloucestershire. At that moment his parents, George Steel Travers Harris and Caroline Maria Elliot, were on leave from India where George worked as an architect in Gwalior. The family returned to India where Arthur remained with his parents until the age of five, when they sent him back to England to go to school. He spent twelve years separated from his parents. He went to kindergarten in Cheltenham before moving to preparatory school in Slough. His brothers Murray and Frederick and two cousins were at the same school. He moved on to Allhallows Grammar School in Honington. As an eighteen-year-old Harris fell out with his parents over their wish that he would enter the army and he decided to emigrate to Rhodesia. He arrived there in early 1910. He spent his first few months at 'Rhodes Estate', where he learned a bit of the native language and farming. He became involved in the transport business, farming and gold mining. In November 1913 he was made farm manager at Lowdale.

First World War

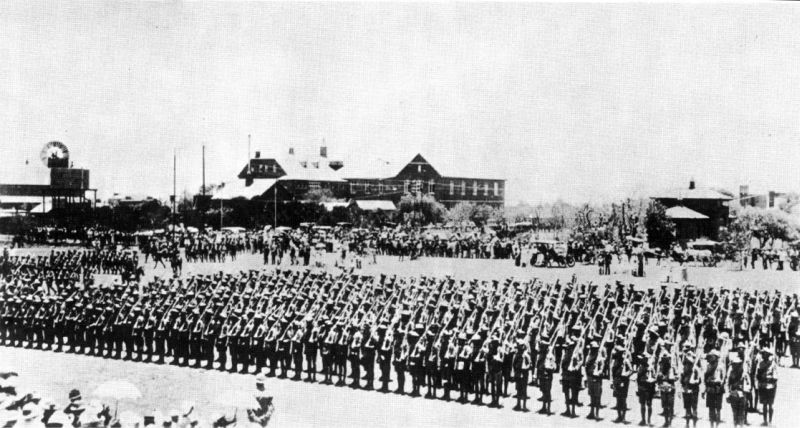

When the First World War broke out Harris felt he had to do his bit for the British Empire. He joined the 1st Rhodesian Regiment as a bugler. After his training Harris' unit was sent to the German colony of South-West Africa (today's Namibia). Initially, it was their task to protect engineers who were replacing railway tracks. When the Allied forces started their advance, Harris was engaged in his first battle on 26 April at Trekkopes. One other particular event during this campaign made an impression on Harris when the single German aircraft in South-West Africa started dropping artillery shells on them. The incident gave Harris his first experience of aerial bombing. After the campaign in South-West Africa, the 1st Rhodesian Regiment was disbanded and Harris was discharged on 31 July 1915.

He returned to Lowdale, but only for a short period of time. He wanted to be involved in the 'real war' in Europe. He travelled to England where he took up residence again with his parents in London. He tried to join the cavalry and artillery, but to no avail. So he joined the Royal Flying Corps (RFC). He was trained at Brooklands and was promoted to Second Lieutenant on 6 November 1915. He continued his training and became a RFC pilot on 29 January 1916. He was posted to 19 Reserve Squadron. Their task was to protect London against the German Zeppelins. He remained at the squadron until July. He was appointed to command No.38 Squadron, only ten months after joining the RFC. A month later, on 30 August, he married Barbara Money. They had met a couple of months previously. A couple of weeks after his wedding, Harris was posted to No.70 Squadron, based in France and equipped with the Sopwith 1½ Strutter. He only stayed there for a few weeks as he crash-landed on 1 October and injured his left forearm in the crash. He was sent back to England. It took him until spring to recover. He returned to France on 18 June 1917 and joined No.45 Squadron. Here he was involved in the Battle for Passchendale, which would have an enormous impact on his thoughts about war. If there would ever be another war, Harris thought there must surely be another way to fight it. Harris was convinced that the bomber offered a better way of doing it. After a couple of weeks Harris was sent back to England for the second time because of flu. When he had recovered, he was promoted to Major and put in command of No.191 Training Squadron. Later he commanded No.44 Squadron. This unit was to be sent to France, but then the Armistice was declared on 11 November 1918.

Interwar period

Harris was awarded the Air Force Cross for his contributions in the war on 2 November 1918 and granted a permanent commission in the newly formed Royal Air Force (RAF) the following year. He choose a RAF career over a return to Rhodesia, also because he and Barbara now had a baby boy, Anthony. Harris commanded No.50 Squadron for a period of eight months, before attending the Andover School of Navigation where he came out top of the 38 students which had started. At 26 April 1920 he took over command of No.3 Flying Training School at Digby. Soon after his second child (Marigold) was born Harris applied for a posting overseas. He and Barbara left for India, where he took over command of No.31 Squadron. One of the airmen under his command was Flight Lieutenant Alec Coryton who served as Harris’ second flight commander. Coryton would serve under Harris again as commander of No.5 Group Bomber Command between April 1942 and February 1943. In July 1922 Harris became Supernumerary at RAF Headquarters in Iraq. Barbara went back to England, as Iraq was too dangerous. At that time she was pregnant for the third time. In November Harris was appointed to command No.45 Squadron, the same squadron with which he had flown over the Western Front in 1917. Here he flew with Flight Lieutenant Ralph Cochrane, who would also serve again under Harris as commander of No.3 and No.5 Group Bomber Command. No.45 Squadron flew transport aircraft and during his command Harris converted it into a bomber unit. He also insisted on operating at night as well, introduced target marking and stressed on good navigation, which deeply impressed people in high places. Harris became known for his leadership talents, inventiveness and determination to exploit the potentialities of air power.

Harris returned to England in October 1924 where he re-joined his wife and three children (Anthony, Marigold and Rosemary). In May 1925 he took over command of No.58 Squadron at RAF Worthy Down, where he kept impressing his superiors with the very high flying standards of his squadron. No.7 Squadron was also based at RAF Worthy Down and was commanded by Wing Commander Charles Portal. The two officers built a friendship and mutual respect. From January 1928 till the end of 1929 Harris attended the Army Staff College in Camberley. In early 1930 he moved to the Middle East again for a series of postings, leaving his family behind again. He became Senior Staff Officer at RAF Middle East Command and served as Supernumerary at Middle East Headquarters and in Iraq. In August 1932 he returned to England and attended No.16 Flying Boat Pilot’s Course and took over command of No.210 Squadron which operated flying boats at Pembroke Dock a year later. Here he met Australian pilot Donald Bennett, who would become commander of No.8 Group Bomber Command in 1942.

In 1933 the Air Ministry decided to develop a strategic bomber force for which the best expertise available was needed. Harris was appointed Deputy Director of Operations and Intelligence and later Deputy Director of Plans. It was a difficult period for Harris. He did not like his desk job and at the same time his marriage fell apart. He and Barbara divorced in 1935. In the meantime the British rearmament had started. Harris spent a couple of weeks in Rhodesia in 1936, assisting the Rhodesian government in setting up its own air force. On 1 April 1937 Harris was promoted to Air Commodore and appointed as commander of No.4 Group Bomber Command. His Commander-in-Chief was Air Chief Marshal Sir Edgar Ludlow-Hewitt, for whom he had the greatest respect. Both men were aware of Bomber Command's many shortcomings (navigational aids in particular), and they exchanged views regularly. Harris was to become the new Air Officer Commanding (AOC) Palestine and Transjordan, but this appointment was cancelled and Harris was sent to the United States. He had to lead the RAF Purchasing Commission, which was tasked to investigate the possibility of ordering aircraft for delivery to the RAF in order to accelerate the expansion of the force. He returned in June 1938 and married for the second time later that month. His new wife was Jill Hearne. Harris was promoted to Air Vice Marshal on 1 July and his posting to Palestine was reinstated. He spent more than a year here, before being diagnosed as having a duodenal ulcer on 12 August 1939. He was sent to England on sick leave.

Definitielijst

- Bomber Command

- RAF unit which controlled strategic and sometimes tactical bombing (as in Normandy)

- cavalry

- Originally the designation for mounted troops. During World War 2 the term was used for armoured units. Main tasks are reconnaissance, attack and support of infantry.

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

- Marshal

- Highest military rank, Army commander.

- RAF

- Royal Air Force. British air force

- Regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

- Squadron

- A military unit in the Belgian navy usually six to eight small ships operating together under one command. The smallest military unit in the Dutch air force of about 350 men. In most countries is the designation of a military unit thesize of a company. It is either an independent unit, such as a battery, or part of a bigger Calvary unit. In the air force it is the designation of a unit of aircrafts.

Images

Arthur Harris in 1915. Source: Air of Authority.

Arthur Harris in 1915. Source: Air of Authority.The Second World War

Air Officer Commanding No.5 Group

Harris was still convalescent when war was declared on Germany on 3 September. He immediately rung the Air Ministry to ask Portal, who was now Air Member for Personnel, for a job, preferably in Bomber Command. Harris was convinced that given the shortcomings of Britain’s armed forces compared with those of Germany, a bomber offensive was inevitable: "I could see only one possible way of bringing pressure to bear on the Boche, and certainly one way of defeating him; that was by air bombardment." Ludlow-Hewitt wanted a new Air Officer Commanding (AOC) for No.5 Group and told Portal he would be delighted for Harris to take over the job. On 11 September Harris was indeed appointed AOC for No.5 Group, a 'heavy bomber' group which boasted ten squadrons equipped with the Handley Page Hampden. Within days he wrote his first letter to Ludlow-Hewitt about the shortcomings of the aircraft, in particular defensive armament. Harris was also worried about the men who flew the aircraft and regularly engaged in informal crew-room discussions with his crews. He visited his squadrons frequently and used the opportunity to give the airmen his advice. The airmen liked Harris, who blended discipline with encouragement, sympathy and understanding.

One of the things on which Harris and Ludlow-Hewitt agreed was the point of lack of operational training. They both regarded it as a weakness for Bomber Command. Harris even wanted to set up his own training organizations. Ludlow-Hewitt insisted on the formation of more Operational Training Unit’s (OTU’s), but the Air Ministry was reluctant to the plans and eventually sacked Ludlow-Hewitt. Harris was upset by the departure of Ludlow-Hewitt, who he described as "the most brilliant officer I have ever met in any of the thee services." Harris disagreed with the sacking of his superior and backed his policy: "without this policy of Ludlow's, the dog would have eaten its own tail to hurting point within a few weeks, and would have been a dead dog beyond all hope of recovery, within a few months. Ludlow-Hewitt saved the situation - and the war - at his own expense."

Although Harris was upset by the departure of Ludlow-Hewitt, he had great respect for his successor, Charles Portal, as well. He knew Portal since they had flown together at Worthy Down. Harris continued to perform well as AOC No.5 Group. He constantly engaged his mind on how to rectify problems and do things better. Under his command, the Group took part in the Battle of Britain and carried out some very important operations, like the precision attack on the Dortmund-Ems Canal on 19 June 1940. Two of his airmen were awarded the Victoria Cross. Harris was concerned about his crews. Anything he could do to minimize aircrew losses took high priority, like lessons in aircraft recognition or modifications to rescue dinghies. Together with Air Vice-Marshal Jack Baldwin, AOC No.3 Group, Harris insisted on improvements on the rescue operations for ditched crews, which resulted in the creation of the Air-Sea Rescue service.

Air Ministry and RAF Delegation

On 24 November 1940 Harris was appointed Deputy Chief of Air Staff at the Air Ministry, where he again worked in close cooperation with Portal, who had been promoted to Chief of Air Staff a month before and had been succeeded by Air Vice-Marshal Richard Peirse as commander of Bomber Command. As London was under attack by the Luftwaffe frequently, Harris did not bring his family into the city and as a consequence of this he would see them only occasionally. In this new role he witnessed the great incendiary attack on London on Sunday evening 29 December 1940. He called Portal to the roof to witness "a sight that shouldn't be missed" and said to him: "They are sowing the wind." Quickly he was back to business advising Peirse to concentrate his bombing offensive against the German synthetic oil plants. But more and more it became clear that Bomber Command’s shortcomings prevented the force to carry out this task by precision attacks only. Harris was becoming convinced that Bomber Command would need to target industrial areas as a whole in order to inflict serious damage on the enemy. In March 1941 a German attack on Yugoslavia seemed to be at hand and Harris proposed that Bomber Command should give the Yugoslavs moral support by a series of attacks on Berlin, Hanover or Cologne. The objective would be to cause the maximum damage to populated areas "as a demonstration of that ruthless force which we shall have to employ against Germany sooner or later if we are to get the full moral effects out of our air offensive." Portal agreed and discussed the idea with Prime Minister Winston Churchill, but the German campaign in Yugoslavia had already come to an end before the plan could be worked out.

Harris did not enjoy his job as Deputy Chief of Air Staff. He preferred an operational command. But in May 1941 he was appointed Head of British Air Staff in Washington. Portal had asked him to go to the United States to lead the RAF Delegation. Together with his wife Jill and daughter Jackie he sailed to the states aboard HMS Rodney. Although Harris was promoted to Air Marshal, the delegation had to act like civilians who represented the Ministry of Aircraft Production, as the United States were not involved in the war yet. It was Harris’ job to guide the inexperienced, but rapidly expanding American service. At the same moment he had to make sure a proportion of the aircraft, equipment and supplies were sent to Britain as part of the Lend-Lease Act. During the first great conference between the leaders of British and American war efforts on 22 December 1941, Portal told Harris he was considered for commanding Bomber Command, as Peirse had come under growing criticism. Portal had suggested to Churchill to send Peirse to the Far East and the Prime Minister agreed. In early January Portal told Harris he wanted him to take over as Commander-in-Chief Bomber Command. Harris sailed for home on 10 February 1942.

Definitielijst

- Bomber Command

- RAF unit which controlled strategic and sometimes tactical bombing (as in Normandy)

- Luftwaffe

- German air force.

- Marshal

- Highest military rank, Army commander.

- moral

- The will of the troops/civilians to keep fighting.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- RAF

- Royal Air Force. British air force

Images

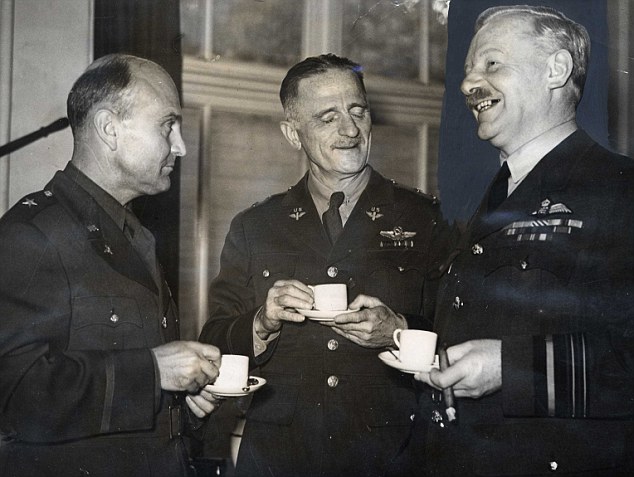

Charles Portal, the man who appointed Harris as C-in-C Bomber Command in 1942. Source: Imperial War Museum.

Charles Portal, the man who appointed Harris as C-in-C Bomber Command in 1942. Source: Imperial War Museum. Air Vice Marshal Richard Peirse, Harris predecessor at Bomber Command. Source: Imperial War Museum.

Air Vice Marshal Richard Peirse, Harris predecessor at Bomber Command. Source: Imperial War Museum.Commander-in-Chief Bomber Command

First months under his command

Harris was appointed Commander-in-Chief Bomber Command on 22 February 1942. He took over from Air Vice Marshal Jack Baldwin, who had acted as C-in-C since Peirse's departure. His force boasted 44 Squadrons of medium and heavy bombers (38 of them operational), 2 Groups of light bombers and 17 OTU’s. This came down to less than 400 serviceable aircraft. The majority of the squadrons were still operating Wellingtons, Whitleys and Hampdens, lacking range and bomb-load. At the time Harris took over command, the future of Bomber Command as an independent force was at stake because of the Butt Report. This investigation had shown that of the two-thirds of crews who claimed to have hit their targets, only a third came within five miles of the aiming point. This proportion was even lower against targets in the Ruhr-area and on moonless nights. Not only in Parliament, but also war correspondents had growing doubts about the effectiveness of Bomber Command and this affected the public opinion too. It seemed Peirse had been overconfident about the work of his command and Harris had to persuade the critics.

The Air Ministry had send Peirse an important new directive on 9 July 1941, which mentioned that precision bombing on military and industrial targets was not practicable anymore. The directive therefore mentioned that the bombers had to concentrate on 'area' targets. Cities which contained installations of military and industrial significance were to be attacked and at the same time these attacks would target the German transportation system as well as enemy morale, particularly that of the industrial workers. On 14 February 1942 it was stressed in a new directive that the primary objective had to be civilian morale. It has often been alleged that Harris was the man behind the strategy of 'area-bombing' , but he wasn't. It was determined by the Air Ministry under Portal's direction and supported by the War Cabinet. Churchill was an advocate of the strategy as well: "When I look round to see how we can win the war I see that there is only one sure path [...] and that is an absolutely devastating, exterminating attack by very heavy bombers from this country upon the Nazi homeland."

Bomber Command carried out a couple of interesting raids in the first two months under its new commander. The Billancourt Renault Factory was attacked on 3 March 1942. The greatest force of bombers so far in the war was sent to the target and the concentration of aircraft over the target and tonnage of bombs dropped exceeded previous records. On 17 April Harris showed that despite the new directive, he still considered precision bombing effective. Twelve Lancasters attacked the U-boat engine plant in Augsburg. However, seven aircraft were lost. A few weeks before the strategy of area-bombing was carried out on a large scale and with great success against Lübeck (28/29 March) and Rostock (four nights between 23 and 27 March).

In his attempt to prove the critics of Bomber Command and the Butt Report wrong Harris had to demonstrate what his command was able to achieve. He decided upon a concentrated attack at maximum strength. He got the backing of Portal and Churchill. Cologne was chosen as the target for an attack which was to be carried out by more than 1000 bombers. Operation Millennium, as the raid was codenamed, was carried out on 30/31 May 1942. 1047 aircraft were dispatched, of which 43 (3.9%) were lost. The attack inflicted heavy damage and gave Bomber Command an enormous boost. Harris: "If I could send 1000 bombers to Germany every night, it would end the war by the autumn. We are going to bomb Germany incessantly [...] the day is coming when the USA and ourselves will put over such a force that the Germans will scream for mercy." At this time these words were what the mass of the British people wanted to hear and impressed Britain’s allies.

Extending the offensive

During the summer of 1942 the Germans were driving the Red Army eastwards again and the Battle of the Atlantic was still full on. Harris was convicted that Bomber Command could play a decisive part and even that it could win the war for the allies, as long as he would get enough heavy bombers at his disposal. Churchill was not persuaded that the command could win the war on its own, but he was convinced it had a major part to play. He assured Harris of his support. The 32 operational squadrons had to be increased to 50 by the end of the year. However, Harris was reluctant to bomb every target which was suggested to him by the Air Ministry. Harris had an honest and realistic view when it came to certain targets, especially oil targets. He responded to the relentless requests to attack oil plants at Schweinfurt and Gelsenkirchen: "This would be a waste of time and effort. They are very small and difficult to find in the smoky and hazy atmosphere of the Ruhr, I do not believe we have ever succeeded in damaging them and thousands of sorties have been wasted in the attempt [...] If we have learnt anything it is that only under very exceptional conditions can the very best crews find these small individual factories in the Ruhr, and then only if luck attends their efforts." He also resisted the early requests to attack Berlin, because of the heavy costs and little success of previous raids on the city. Harris was keen to bomb Berlin, but only when he could make a good job of it. His first raid on the capital was carried out on 16/17 January 1943, eleven months after he had been appointed C-in-C.

By this time, the strategic bomber offensive was not only a military tool to Churchill but also an essential political one with regard to the relation with Stalin and the Soviet Union. For that reason he gave Harris his strongest support. It further convicted Harris that Bomber Command could win the war on its own and from now on he attempted to fulfil what he believed was his command’s ultimate potential. On 3 February 1943 he received a new and important directive to work with. It had been agreed at the Casablanca Conference by Churchill, Roosevelt and the Combined Chiefs of Staff. The directive stated that the primary aim of the British and American bomber forces would be "the progressive destruction and dislocation of the German military, industrial and economic system, and the undermining of the morale of the German people to a point where their capacity for armed resistance is fatally weakened." Historians still discuss the way the directive had to be interpreted. In Harris view it meant that the area bombing offensive had to be extended. He also believed that the German morale was vulnerable at this stage of the war, and were it to be broken Germany might surrender.

To fulfil this task Harris needed a team of subordinate commanders he could depend on. His Groups were commanded by men he knew really well and in whom he had great confidence (Robert Oxland, Roderick Carr and Edward Rice) and with whom he had flown or worked in earlier days (Alec Coryton, Ralph Cochrane, Donald Bennett and Richard Harrison). George Brookes commanded the newly formed Canadian No.6 Group. Harris also depended on Station Commanders and other senior officers on the Group staffs. However, he took a strong line if somebody of his team was out of step. For instance, he sacked Coryton in February 1943 when the commander of No.5 Group was reluctant to send his crews to the Ruhr on a night of bad weather. In February 1944 he also relieved Brookes because he was not impressed by his leadership abilities and appointed Clifford McEwen, in who he had more confidence. This created a picture of a remote, hard and intolerant man. But most of his staff at High Wycombe found him kind and considerate, a man who would listen carefully and act decisively. They regarded him as the strong man who moved the command into higher gear. He also held the trust, loyalty and respect of his airmen, although they suffered terrible casualties and hardly saw him at their airfields. Harris knew that the job his crews had to carry out made substantial casualties inevitable, so he kept insisting on aircraft and techniques needed to help his crews defending themselves and minimizing their losses. In this way his crews felt their commander was concerned about what they were doing. Historian Max Hastings stated: "He was passionately concerned to give every man in his Command the best possible chance of survival."

Bomber Command had been tasked with an offensive against the U-boat bases until February 1943. By this time Harris started his main offensive. The Battle of the Ruhr commenced and lasted for four months, in which 43 major operations were undertaken. The main targets were the Krupp armament works in Essen, the Nordstern synthetic-oil plant in Gelsenkirchen, and the Rheinmetal–Borsig plant in Düsseldorf. The most famous raid of the campaign was Operation Chastise (16-17 May 1943), better known as the Dams raid. This was an attempt to breach the Möhne, Eder and Sorpe dams to flood to Ruhr valley. The specially formed and trained 617 Squadron managed the destruction of two of the dams. The attack was an immense boost to morale, but eight out of nineteen of Harris’ very best crews had been lost in the attack and they were almost impossible to replace. Therefore it was no real option to change strategy and persist with such operations. But Harris wanted 617 Squadron to be retained for occasional operations requiring special training and skills, like the attack on the Dortmund-Ems Canal during the night of 15/16 September 1943. In this raid losses were again very high, with five out of eight aircraft not returning.

Hamburg to Berlin

Before the Battle of the Ruhr had ended, Harris had already started the Battle of Hamburg; a series of attacks which began on 24 July and lasted eight days. Harris had been encouraged by Portal and the Admiralty to bomb the city, as it was the enemy’s greatest port and the centre of its shipbuilding industry. The campaign, codenamed Operation Gomorrah, was carried out in cooperation with the USAAF 8th Air Force. One of the raids became particularly well-known. During the night of 27/28 July 787 aircraft attacked the city. The combination of high temperatures, drought and concentrated bombing created a firestorm which raged for about three hours and approximately 40.000 people were killed. Most of them died of carbon monoxide poisoning when all the air was drawn out of their shelters. Albert Speer, Hitler’s Armaments Minister, stated that six similar attacks might end the war. But Bomber Command was still not strong enough the carry out attacks on such a scale frequently.

In August 1943 Harris was ordered to bomb Peenemünde, where the Germans had a research and development station for the development of long-range rockets. 596 aircraft were sent to the target for a precision attack which was carried out at low level and in bright moonlight. The operation turned out to be a success and is regarded as one of Harris’s most daring. He suggested another daring raid to Churchill that month. Harris wanted to bomb Mussolini’s office and residence to encourage an Italian surrender. He had selected 617 Squadron for this special operation. But Churchill turned the plan down and ordered Harris to carry out area bombing attacks on Milan, Turin and Genoa to ensure that the Italian government would agree with the Allied surrender requirements.

Encouraged by Churchill and Portal, Harris launched the Battle of Berlin that same month. He ordered three attacks against the city, but success was only moderate and losses were high. Harris decided to postpone his offensive until November 1943. In October he received a message from Churchill: "The War Cabinet have asked me to convey to you their compliments on the recent success of Bomber Command.[…] Your Command is playing a foremost part in the converging attack on Germany now being conducted by the forces of the United Nations on a prodigious scale. Your officers and men will, I know, continue their efforts in spite of the intense resistance offered, until they are rewarded by the final downfall of the enemy." In November the main part of the Battle of Berlin commenced. A series of 16 heavy attacks on the German capital were carried out over the next four months. Apart from fierce defences, the crews also encountered wintry weather conditions on these long flights to Berlin. Harris had forecast that the capital would be reduced to ruins at the end of the battle and German morale would collapse. 8700 sorties were carried out, from which 500 aircraft failed to return. Although heavy damage had been inflicted, the Germans were nowhere near surrender. However, Churchill used the attacks in a political way as well, referring to the attacks in messages to Stalin, who told him in reply "to intensify it using all means."

The last year of the war

In early 1944 both Harris and Lieutenant Colonel Carl Spaatz (commander of the USAAF) were still convinced the allied bomber force could force Germany to surrender, but Bomber Command was ordered to co-operate in the preparations for Operation Overlord and put under command of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF). Harris did not agree, he was worried by the possible recovery of German industry and night-fighter forces. Nevertheless, Bomber Command was ordered to bomb coastal defences and key railway centres in France and Belgium. The bombers carried out some 60 operations as part of the invasion preparations. Solly Zuckerman, the scientist who had come up with the Transportation Plan, later wrote in his diary: "The amazing thing is that Harris, who was even more resistant than the Americans, has in fact thrown himself whole-heartedly into the battle [..] and has contributed more to the dislocation of enemy communications, etc, than any of the rest." After D-Day, Harris requested to resume strategic attacks, but General Dwight Eisenhower decided the bombers had to be used in support of his land forces. When the Germans launched their V-1 bombs against London a week after D-Day, Harris was ordered to carry out attacks on the supply and launching sites as part of Operation Crossbow.

When the allied armies finally broke through the German defences a swift advance to the German frontier followed. Bomber Command played little part in the advance. Bomber Command was relieved from control by SHAEF in September. After the failure of Operation Market Garden in September 1944 the allied armies had come to an halt and the war would not be ended by Christmas. Harris believed full advantage had to be taken of air superiority to "knock Germany finally flat" and prepare the way for the ground troops and wrote this in a letter to Churchill. The Prime Minister replied: "I agree with your very good letter. [...] I am all for cracking everything in now on to Germany that can be spared from the battlefields." This encouraged Harris, as well as the latest directive from the Air Ministry in which Bomber Command's overall mission was stated as "the progressive destruction and dislocation of the German military, industrial and economic systems and the direct support of land and naval forces." Targets were threefold: oil production industry, the German transportation system and general bombing of German industrial cities. The bomber force was still growing considerably. Harris could draw on approximately 1400 operational bombers per day.

A second Battle of the Ruhr was launched in the autumn of 1944. Although it was mentioned under that title in the Official History, it isn’t widely remembered. The most well-known attack is Operation Hurricane, the codename for two raids by more than 1000 bombers on Duisburg on 14/15 October 1944. But Bomber Command had run out of large cities to target and started to bomb smaller industrial towns, like Darmstadt, Bremerhaven, Bonn and Freiburg. On 12 November No.9 and No.617 Squadron sunk the battleship Tirpitz as part of Operation Paravane. This brought Bomber Command excellent press publicity, as well as congratulations from the King, the Prime Minister and the Admiralty. But gradually arguments arose about the use of Bomber Command at this stage of the war. Although many improvements in bombing and navigation had become available, Harris still devoted a large portion of his bombers to area bombing on German cities. Harris claimed the weather was often not favourable for bombing oil and communication targets. But great numbers of bombers were sent to German cities to carry out area bombing in both good and bad weather. Harris critics believed that persisting the strategy of area bombing was unnecessary at this stage of the war.

In the meantime British Chiefs of Staff had come up with the plan of Operation Thunderclap: an all-out attack on civilian morale which might be decisive. An attack on Berlin was discussed, but a modified form of the plan was eventually carried out against Dresden after Air Vice Marshal Sidney Bufton (Director of Bomber Operations) suggested that the Thunderclap plan could be used in support of the Soviet advance. Churchill would soon leave for the allied conference at Yalta. Here the Russians requested strategic air attacks against Germany’s eastern communications. The Air Ministry and Chiefs of Staff approved and Harris was given his orders. On the night of 13/14 February 1945 805 aircraft were dispatched to the city and the heart of Dresden was destroyed in an atrocious firestorm. An estimated 25,000 people, mostly civilians and refugees, were killed in the attack. The news of the destruction of Dresden led to anger in the British Parliament. Churchill, who had been a strong advocate of area bombing and had a personal role in setting up the Dresden attack, now composed a memorandum: "It seems to me that the moment has come when the question of bombing of German cities simply for the sake of increasing the terror, though under other pretexts, should be reviewed. […] The destruction of Dresden remains a serious query against the conduct of Allied bombing." The destruction of Dresden has come to symbolise the bombing of Germany in the Second World War and Harris was publicly seen as the man responsible for it. Harris called the allegations of terror bombing against him and his men an insult both to the Air Ministry and Bomber Command.

Bomber Command’s offensive continued and in March 1945 a greater tonnage of bombs was dropped than in any other month of the war. Oil production industry and the German transportation system were attacked, but Harris still sent his bombers to industrial towns as well that month. His targets in the last five weeks of the war were strictly military ones. His men also played an important part in Operation Manna (29 April to 8 May), the food droppings over Western Holland, and the return of liberated Prisoners of War to Great-Britain (26 April to 6 June).

Definitielijst

- area bombing

- Aerial bombardment targeted indiscriminately at a large area. Prohibited since 1977 by the Geneva Convention. Also known as carpet bombing, obliteration bombing and moral bombing.

- battleship

- Heavily armoured warship with very heavy artillery.

- Bomber Command

- RAF unit which controlled strategic and sometimes tactical bombing (as in Normandy)

- Casablanca Conference

- Conference between the leaders of Great Britain and the USA (Churchill and Roosevelt). The conference took place from 14 to 24 January 1943.

- D-Day

- The day of the long awaited invasion of western Europe in Normandy, France, 6 June 1944. After a long campaign of deception the allies attacked the coast of Normandy on five beaches to begin their march on Nazi Germany. Often explained as Decision Day, though this is entirely correct. The D stands for Day as generally used in military language. In this case it means an operation beginning on day D at hour H. Hence “Jour J“ in French.

- firestorm

- Happened spontaneously in Hamburg in 1943. This was the ultimate goal of each bombardment. The firestorm could no longer be extinguished and burned down everything in its path. Surface temparatures of 800-1,000 degrees Celcius and wind speeds upto 240 km/hour, so double hurricane force, were reported. Bomber Command only succeeded a few times in creating the desired firestorm, that is in Hamburg on 27 July 1943, Kassel on the 22 October 1943, Darmstadt on 11 September 1944 and Dresden on 13-14 February 1945. Bomber Command always selected the medieval city centres (Altstadt) as target because of the many high wooden buildings and narrow streets.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Krupp

- German family of steel and weapon’s manufacturers.

- Marshal

- Highest military rank, Army commander.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- SHAEF

- Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force, the Allied High Command in Western-Europe after the Normandy landings.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- Squadron

- A military unit in the Belgian navy usually six to eight small ships operating together under one command. The smallest military unit in the Dutch air force of about 350 men. In most countries is the designation of a military unit thesize of a company. It is either an independent unit, such as a battery, or part of a bigger Calvary unit. In the air force it is the designation of a unit of aircrafts.

- strategy

- Art of warfare, the way in which war should be conducted in general.

- U-boat

- The German name for a submarine. German U-Boats (Submarines) played a very important role during the course of warfare until May 1943. Many cargo and passenger ships were torpedoed and sunk by these assassins of the sea.

Images

Harris was visited by HM King George VI and Queen Elizabeth at Bomber Command Headquarters. Source: The National Archives.

Harris was visited by HM King George VI and Queen Elizabeth at Bomber Command Headquarters. Source: The National Archives.After the war

Debate about Harris and Bomber Command

After the war had come to an end, Portal wrote to Harris "how deeply and sincerely grateful he felt for the magnificent work he and his Command had done." But a few days later, on 13 May, Churchill held his ‘VE Speech’. It reflected on the various battles which were fought and on the branches of the army which had been involved in them. However, of bombing operations there was not a word. It was though the bomber offensive had never been. Churchill did sent Harris a personal message on 15 May in which he referred to the glorious and decisive contribution of Bomber Command in the allied victory and expressed his deep sense of gratitude. But Harris felt bitterly affronted by the lack of public support from Churchill and the omission of Bomber Command in his ‘VE Speech’. The Prime Minister seemed to recoil from the consequences of the bomber offensive. Harris felt even more affronted by Churchill when he learned his men were not awarded a campaign medal. He kept insisting on recognition for his air and ground crews, but to no avail. On 13 June Harris was awarded the Knight Grand Cross, but Harris immediately stated he refused honours as long as the injustice to his men persisted. Harris would also become the sole Commander-in-Chief who did not receive peerage. Almost certainly, Harris was offered becoming a peer, but rejected the offer because of his loyalty to the men of Bomber Command.

Bomber Command’s contribution to the allied victory has often been discussed and Harris was a key figure in this discussion. He himself reflected on the war in his Despatch and stressed that in comparison to the First World War, his campaign had saved countless lives elsewhere in all three services, and also among British civilians. Albert Speer wrote during his time in prison: "It opened a second front long before the invasion in Europe. [...] This was the greatest lost battle on the German side." In 1976 Speer sent Harris a copy of his book, with a note: "I hope it will please you to read these facts which are always underestimated." History professor Richard Overy also thinks the bomber offensive has been underestimated. In his view bombing "did undermine German economic potential, erode popular morale and distort German strategy." He agrees with Harris’ biographer Henry Probert that Harris can be classified as one of the great commanders of the Second World War. But other historians have had differing views. Historian Max Hastings for example, states: "The cost in life, treasure and moral superiority over the enemy tragically outstripped the results it achieved." Besides that, Hastings strongly criticizes Harris' fixation on continued area bombing in the final period of the war. Historian Peter Johnson considers that from April 1943 area bombing was unjustified.

Retirement

Harris left Bomber Command when he retired on 15 September 1946. He had been promoted to Marshal of the Royal Air Force on 1 January 1956. Before his retirement he had written the Despatch on Bomber Command's wartime operations. He also attended several ceremonies and meetings. He was invited to represent Great Britain at the Victory Parade in Oslo on 30 June 1945. In 1947 Harris published his memoirs, titled ‘Bomber offensive’, in which he reflected on the war and the allied bomber offensive. In one of the most quoted lines he refers to the bombing of Hamburg: "In spite of all that happened at Hamburg, bombing proved a comparatively humane method. For one thing, it saved the youth of this country and of our allies from being mown down by the military as it was in the war of 1914-1918." Shortly after publishing his personal memoir, Harris and his family left for South Africa, where he became Managing Director of Safmarine, a shipping line between South Africa and the United States.

On 7 April 1952 Harris was awarded a baronetcy. It was pushed through by Churchill, who had won the elections in 1951. Harris had returned to the United Kingdom and attended the Coronation of the new Queen on 2 June 1952. He was also present at the opening of the Runnymede Memorial (October 1953) and the unveiling of the Memorial Window in Lincoln Cathedral (May 1954), two major events associated to Bomber Command. But Harris turned down any further invitations to RAF functions. Harris moved to Goring-on-Thames in Oxfordshire, where he spent time with his wife, children and grandchildren. Old wartime colleagues visited him here, like Americans Ira Eaker and Carl Spaatz and Canadian Clifford McEwen, of whom Harris thought has never been adequately been recognized for his contributions in the war. Ralph Cochrane, Robert Saudby (his deputy at Bomber Command) and Eric De Mowbray (his senior naval liason officer) regularly came along as well.

Sir Arthur Harris passed away at home on 5 April 1984 at the age of 91. His funeral service took place on 11 April with military honours in the parish church. Harris is buried at Burntwood Cemetery near the village. On the day of his burial, a Lancaster made a fly past to pay the RAF's closing tribute. On 31 May 1992 a statue of Harris was erected outside the RAF Church of St. Clement Danes in London. It was unveiled by the late Queen Elizabeth. The inscription mentions: "In memory of a great commander and of the brave crews of Bomber Command. More than 55.000 of whom lost their lives in the cause of freedom. The nation owes them an immense debt." One of the people who attended the ceremony was the famous bomber pilot Leonard Cheshire, who "would have gone even if I had to be carried on a stretcher." But the ceremony was interrupted by a small number of protestors and the statue of Arthur "Bomber" Harris had to be kept under 24-hour guard for several months as it was often damaged. Such was – and still is – the controversy the allied bombing campaign caused.

Definitielijst

- area bombing

- Aerial bombardment targeted indiscriminately at a large area. Prohibited since 1977 by the Geneva Convention. Also known as carpet bombing, obliteration bombing and moral bombing.

- Bomber Command

- RAF unit which controlled strategic and sometimes tactical bombing (as in Normandy)

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Marshal

- Highest military rank, Army commander.

- moral

- The will of the troops/civilians to keep fighting.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- RAF

- Royal Air Force. British air force

- second front

- During World War 2 the name of the front that the American and Brits would open in the West to relieve the first Russian front.

- strategy

- Art of warfare, the way in which war should be conducted in general.

Images

Information

- Article by:

- Pieter Schlebaum

- Published on:

- 19-01-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!

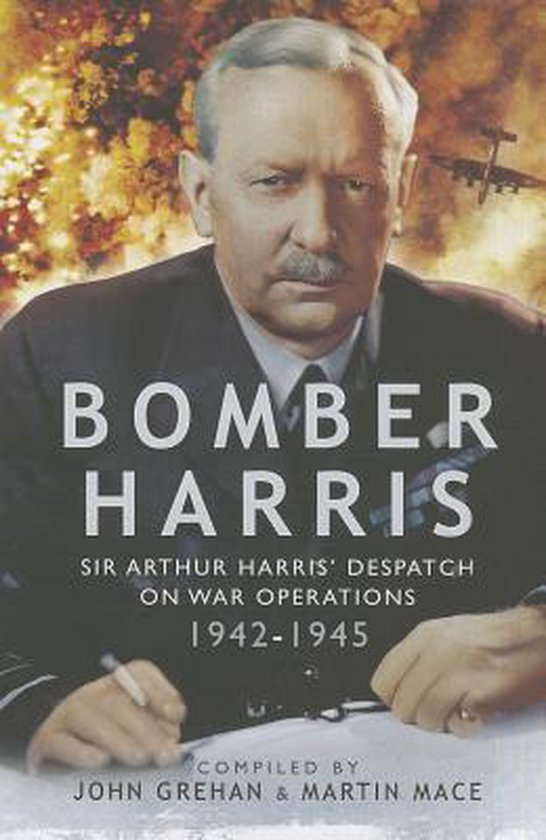

Related books

Sources

- HARRIS, A., Bomber Offensive, Pen & Sword Books, Barnsley, 2005.

- HASTINGS,MAX, Bomber Command, Pan Macmillan, 2012.

- MACE, M. & GREHAN, J., Bomber Harris, Pen & Sword Books, Barnsley, 2014.

- MIDDLEBROOK, M. & EVERITT, C., The Bomber Command War Diaries, Midland Publishing, 2011.

- OVERY, R., Why the Allies Won, W.W. Norton, New York, 2006.

- PROBERT, H., Bomber Harris, Greenhill Books, London, 2006.