Introduction

During the occupation of the Netherlands, the Germans built various types of concentration camps. The three most important camps were located in Amersfoort, Westerbork and Vught. Camp Vught took up a special position, because it was in fact the only official concentration camp in the Netherlands. The camps in Westerbork and Amersfoort were so-called Durchgangslager (transit camps), while camp Vught was a Konzentrationslager (concentration camp).

What was the function of this concentration camp, who were the people that were imprisoned here and what role did the camp play within the Endlösung (final solution), the extermination of the European Judaism? These are some of the questions we will try to answer in this article.

Definitielijst

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Endlösung

- Euphemistic term for the final solution the Nazis had in store for the “Jewish problem”. Eventually the Endlösung would get the form of annihilating the entire Jewish people in extermination camps.

- Judaism

- Monotheistic religion developed among the ancient Hebrews.

Images

The creation

Camp Vught was built and organised according to the German model. The official name of the camp was Konzentrationslager Herzogenbusch, but in this article we will refer to the more common Dutch name. Just as the concentration camps in Dachau, Buchenwald and Mauthausen, the camp was under command of the SS-Wirtschafts- und Verwaltungshauptamt (SS-WVHA), the economical headquarters of the (SS) in Berlin. The other camps in the Netherlands, including the ones in Amersfoort and Westerbork, were managed by the Sicherheitsdienst (SD, Security Service).

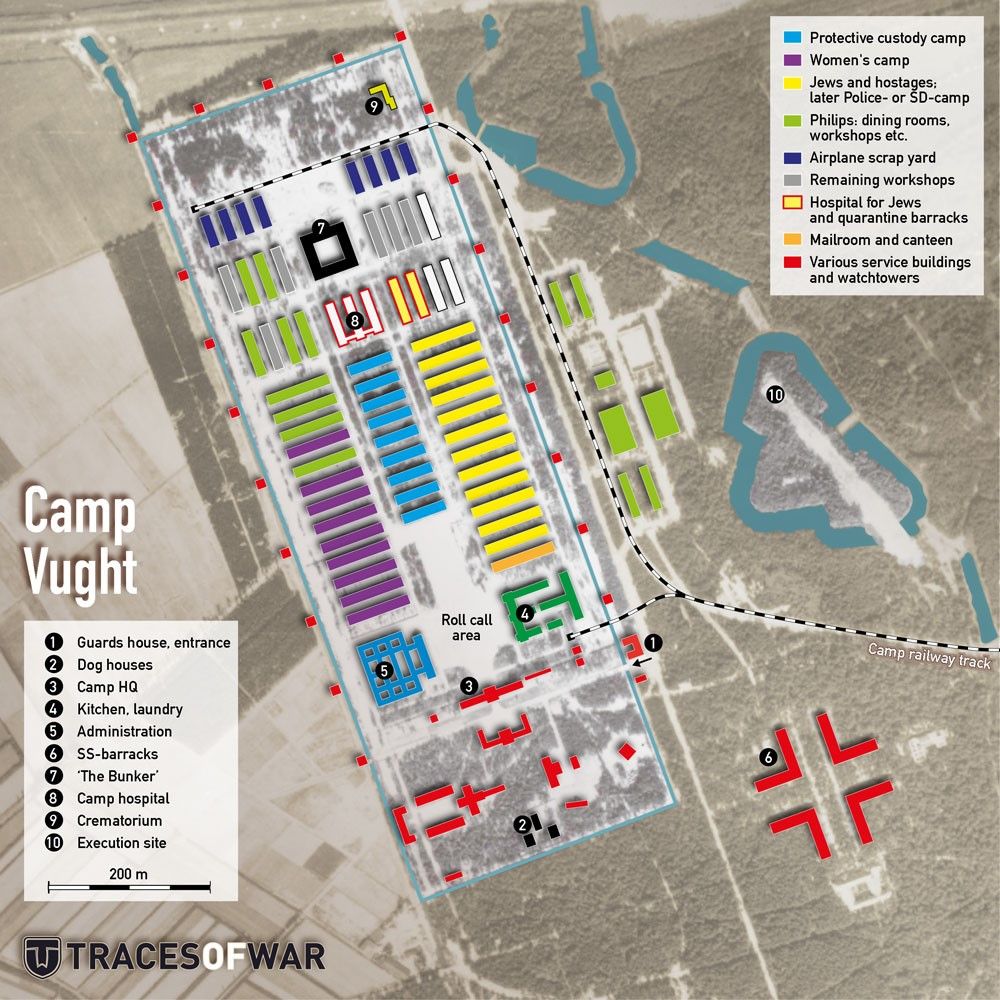

Camp Vught was built because the German occupier needed more prison space. The transit camps in Amersfoort and Westerbork no longer were sufficient. The camp had to serve as a Schutzhaftlager, a prison camp for various groups of prisoners who were dangerous to the state, such as political opponents and resistance fighters, but also homosexuals. Part of the camp functioned as a refugee camp and later as a transit camp for Jews. Below you will find an overview of the different departments of camp Vught throughout its existence.

| As of 13 January 1943 | Schutzhaftlager |

| As of 16 January 1943 | Judenauffanglager, later Judendurchgangslager |

| As of February 1943 | Geisellager |

| February/March 1943 | Studentenlager |

| As of 12 June 1943 | Frauenkonzentrationslager |

| August 1943 | Polizeiliches Durchgangslager |

| As of June 1944 | SD-Lager |

The heath where the Germans built the concentration camp was property of the Dutch government and could therefore easily be confiscated. The camp site was well shielded off from the outside world and was located near a rail road and highways. The location was also suitable because of the short distance to ’s-Hertogenbosch, where important government agencies and the SD and justice department were located.

Definitielijst

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Mauthausen

- Place in Austria where the Nazi’s established a concentration camp from 1938 to 1945.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Images

Structure

The construction of camp Vught started in 1942. People living in the neighbourhood thought that a military barracks was being built, but this suspicion proved wrong, when on 13 January 1943 the first prisoners arrived in Vught. It was a group of 250 starved and knackered prisoners that were being transferred from camp Amersfoort. The majority of them were non-Jewish. When they arrived the camp had not yet been completed. The prisoners had to complete the build themselves under abominable conditions. Meanwhile more prisoners arrived in the camp. The terrible conditions already resulted in hundreds of deaths in the first few months of the existence of the camp.

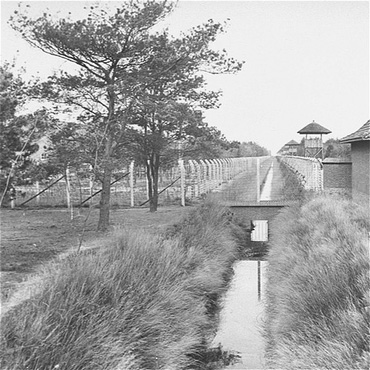

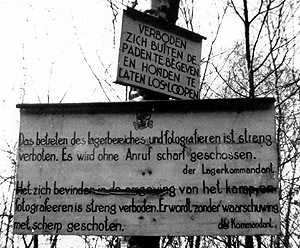

The camp site was over a kilometre long and 350 metres wide. The site was surrounded by a ditch which was dug by prisoners and was fenced off with barbed wire on both sides. A watchtower was positioned every 100 metres, manned by guards with machine guns and searchlights. The territory around the camp was off-limits. There were signs with the threatening text: "It is strictly forbidden to stay in the vicinity of the camp or to take photographs. Live ammunition will be used without warning." However, the people living in the neighbourhood of the camp soon understood that it was being used as a prison camp, because prisoners were being transported from station Vught on foot, under heavy guarding by the SS and the Dutch police. When prisoners were released or being deported, they had to take the same route in reversed direction, again by foot. Because the people of Vught became more hostile against this procedure, the SS later used busses to transport the prisoners. At the end of 1943, a bypass from the railroad to the camp was built, which later was also used for the transport of goods.

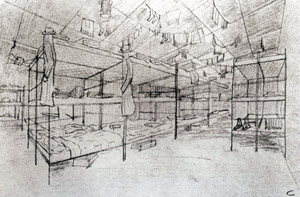

In the camp 29 barracks were used as living barracks. The construction of the hutted camp was financed with stolen Jewish capital. The first barracks were made out of wood, but later they used stone. A stone barrack would house 240 prisoners, but during busy periods, the capacity was often exceeded. Each barrack consisted of two wings which mirrored each other. Each wing had a washing area with toilets, a dining room and sleeping quarters. The barracks were densely populated and there was no privacy. Even between the toilets and the washing room there was no enclosure. In the sleeping quarters the prisoners slept in 3-storey bunkbeds. Each prisoner received one blanket that often wasn’t cleaned and most blankets had already been used by several people. The straw mattresses were also unhygienic.

At the end of 1943, a crematorium and a prison called The Bunker were put into use in camp Vught. The crematorium building was located on a closed off terrain of the camp. This site was off-limits to prisoners that did not work there. In the crematorium building among other things were a medical room and an administration room located. The medical room was used by the Lagerarzt, the camp doctor. The first camp doctor in Vught was the 23-year old SS-Untersturmführer Neier. After a couple of months, he was succeeded by the more experienced doctor Wolter. The doctors in Vught did not carry out medical experiments, like they did in the concentration camps in Germany and Poland. The medical treatment in the sickbay was performed by the prisoners themselves.

In the administration room the personal details of prisoners who had died, were being kept in a Sterbebuch (death book). This was also the place where autopsy reports were drawn up and filed. According to official regulations an autopsy had to be performed on all deceased prisoners. If during the autopsy any abnormalities were discovered to tissue or organs, it could immediately be further investigated in the laboratory, which was also located in the crematorium building.

A so-called kistgalg could also be found in the crematorium building. As far as is known it was never used. However, the gallows which were set up outside of the crematorium were used. In September and October 1943, twenty-seven Belgian resistance fighters who were sentenced to death, were hanged here. Nowadays, the gallows are no longer present in the former camp, because the execution instruments were set on fire after the liberation.

Although the first victim in camp Vught – an 80-year old Jewish man who could not keep up with the marching pace from station Vught to the camp – was buried at the Jewish cemetery in Vught, all the later victims were buried or cremated in one of the three ovens in the camp. The first oven that was used, was mobile and was used until the crematorium building with two fixed ovens was built. These two ovens were manufactured by the company Topf & Söhne. This company also built the ovens for the other concentration and extermination camps. All the dead, who had already been buried before the crematorium was put into use, were exhumed and their burial remains were cremated subsequently. Initially the ashes were collected on the crematorium site in pits, but later, two ash pits behind the crematorium were created for this purpose. Every year on 4 May, a commemoration takes place at this location.

Definitielijst

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Images

To keep unwanted visitors away such sign boards were placed in te surroundings of the camp. Source: www.philips-kommando.nl.

To keep unwanted visitors away such sign boards were placed in te surroundings of the camp. Source: www.philips-kommando.nl. Drawing of a dormitory in one of the barracks. Source: www.philips-kommando.nl.

Drawing of a dormitory in one of the barracks. Source: www.philips-kommando.nl. The gallows which stood outside. Source: www.philips-kommando.nl.

The gallows which stood outside. Source: www.philips-kommando.nl. The removable crematory. Source: Jewish Virtual Library.

The removable crematory. Source: Jewish Virtual Library.Living conditions

Although everyday life in camp Vught was comparable to that in the concentration camps in Poland and Germany, there was one major difference: camp Vught was set up as a model camp and in some ways it was just that, because the regime was less hard than was the case in other concentration camps. This certainly did not mean that life in camp Vught was enjoyable, but chances of survival were relatively large. There were no gas chambers in Vught and there was no case of ‘Vernichtung durch Arbeit’ (extermination through labour). The death rate was therefore not even 1%, while in some concentration camps the death rate exceeded 50%.

They chose to treat prisoners less hard in camp Vught, because they did not want to encourage the Dutch population to resist. The Nazis were not afraid of that in their own country, because the majority of the Germans supported National Socialism. Moreover, they had become used to the existence of concentration camps since 1933. Also in Poland they were not afraid that the concentration camps would cause the people to offer resistance, because the German administration in Poland would use strong-arm tactics. Polish citizens were viewed as Untermenschen (inferior people), while they regarded the Dutch as friendly folk that was racially equivalent to the Germans.

Despite the fact that camp Vught belonged to the concentration camps with the highest chance of survival, the prisoners led a miserable life. After all, the camp had to have a terrifying effect. Just as in every other concentration camp they stripped the prisoners from their identity by giving them a number and each prisoner had to wear the same striped uniform (now known as striped pyjamas). They had to do hard labour with the exemption of Sunday afternoon. Workdays were long, but the work they had to perform was less hard than in other concentration camps. Each workday started with a roll call in the designated roll call area. Despite rain or cold: the prisoners would stand there in their striped pyjamas waiting until everybody had been counted and the Arbeitskommandos (work commandos) had been put together. Some prisoners worked outside the camp and had to travel great distances to their work site on wooden shoes that were too small.

Especially during the first winter the living conditions in the camp were very tough. The construction was not yet completed: the glass had not yet been placed in the windows of the barracks, hygiene was bad and drinking water was polluted. Every day prisoners died. The food situation was also bad, but got better as of 1943, partly thanks to aid parcels which were allowed to be distributed in the camp. These food parcels were put together by private individuals or by the Red Cross and were a welcome and often necessary change to the never changing menu of soup. Sometimes pea or pearl barley soup, but usually the prisoners ate watery cabbage soup. That’s why the street along the kitchen soon was nicknamed the Koolsingel (cabbage avenue). The prisoners could also buy extra food to complement their ration with special camp money.

As was the case in other concentration camps, the lack of privacy in camp Vught was an important means to oppress the prisoners. Ex-policeman Wim Vlijm was imprisoned from 12 March 1943 up to 8 August 1944 in camp Vught. He was arrested because together with ten colleagues he had refused to arrest Jews and to transport them to Westerbork. According to Vlijm there was no privacy whatsoever: "You were never alone, always in the company of others. Everything you did, even breathing, did not go unnoticed. The barracks I stayed in, had a sort of room with long tables and benches. There was something of a washing room where you would all sit next to each other. Everyone could see each other’s buttocks. At first that was kind of weird, but you get used to it."

Not only the lack of privacy, but also the constant presence of guards made the living conditions in camp Vught very difficult. The prisoners were regularly faced with humiliation and abuse by camp guards. Wim Vlijm explains "(...) if the SS-ers were at it, they would come in at midnight, when we were just asleep and then we had to jump out of bed and lie underneath it. If you were not fast enough you would get kicked under it." But mostly such harassment and humiliation did not go any further. Gruesome abuse followed by death, as frequently took place in most concentration camps in Germany and Poland, did not happen in camp Vught. One incident though is the exception: the so-called Bunker Tragedy.

The Bunker Tragedy took place in the night of 15 to 16 January 1944. The victims in this tragedy were women from the women camp that was part of camp Vught since 1943. After one of the women from barrack 23 B was locked up in the camp prison - the Bunker - several women protested against this. In retaliation, camp commander Grünewald decided to lock up as many women as possible in once cell. 74 women were packed together in cell 115 – a space of only 9 square metres. There was hardly any ventilation in the cell. Tineke Wibaut was one of the women locked up in cell 115. She explains that when the lights went out, panic broke loose: "It was a strange sound that slowly build up, would then fade away again and would then build up again. The sound was produced by praying, screaming and screaming women. Some women tried to rise above the noise to try and calm down everyone so that no oxygen would be wasted. Sometimes this would help, but then it would start all over again. It did not stop and continued all night, but the noise became less loud. The heat became suffocating."

When the doors were opened the next day, ten women had suffocated. The tragedy soon became known outside the camp and was extensively written about by the illegal press. Of course this was a thorn in the flesh of the Nazi command in the Netherlands, because they wanted to prevent such abuse from taking place in the model camp Vught. Such incidents could increase resistance in the Netherlands. To prevent further negative publicity, action was taken: camp commander SS-Sturmbannführer Adam Grünewald and contributories were court-martialled for their part in the Bunker Tragedy. Grünewald was degraded to the position of soldier and was replaced by SS-Sturmbannführer Hans Hüttig.

Definitielijst

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- heat

- High-explosive anti-tank warhead. Shaped charge projectile to punch through armour. Used in e.g. bazooka or in the Panzerfaust.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- National Socialism

- A political ideology drawn up by Hitler based on the superiority of the German race, the leader principle and fierce nationalism that was fed by the hard Peace of Versailles. National socialism was anti-democratic and racist. The doctrine was elaborated in Mein Kampf and organised in the NSDAP. From 1933 to 1945 National socialism was the basis of totalitarian Germany.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Socialism

- Political ideology aiming at slight or no class differences. Means of production are owned by the state. Evolved as a response to capitalism. Karl Marx tried to substantiate socialism scientific.

Images

The Bunker, in which te Bunker Tragedy took place. Source: www.philips-kommando.nl.

The Bunker, in which te Bunker Tragedy took place. Source: www.philips-kommando.nl.Prisoners

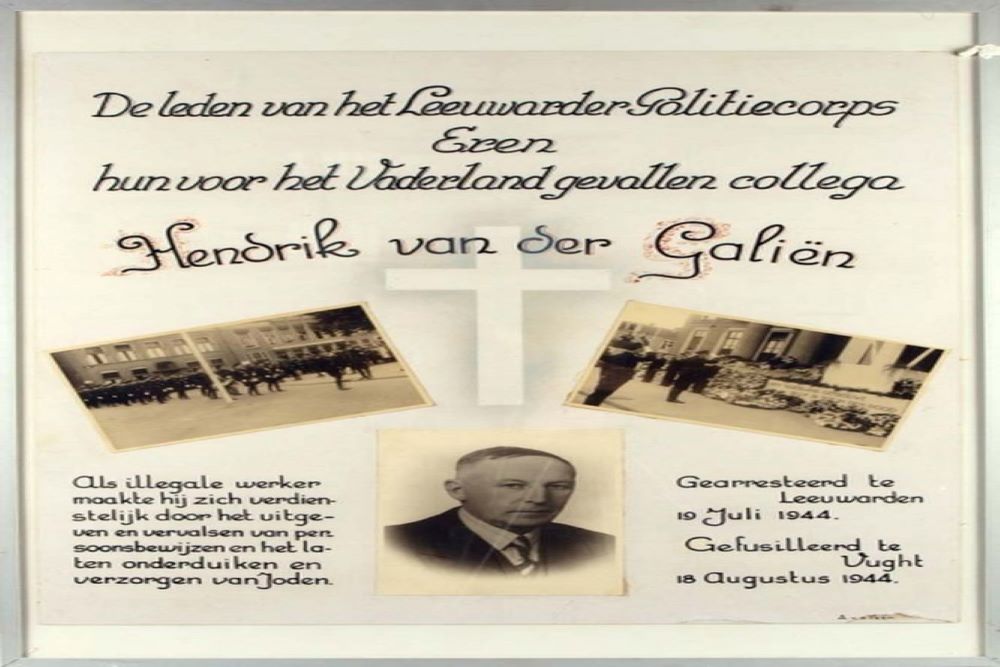

In total about 31,000 prisoners stayed in camp Vught between January 1943 and September 1944. Only ninety of them managed to escape. Mainly Dutch citizens, but also Belgian and French citizens were imprisoned. About 12,000 camp prisoners were Jewish. Many of them had a temporary exemption from transport to Germany or Poland. They had to perform hard labour in the camp. Besides Jews, also political prisoners, resistance fighters, Sinti and Roma (gipsies), Jehovah witnesses, homosexuals, vagabonds and criminals were imprisoned. Also people who had helped Jews to go into hiding, people who had distributed illegal documents and people who refused Arbeitseinsatz were imprisoned in camp Vught for a short or longer period of time. However, the largest group of non-Jewish prisoners was imprisoned in camp Vught because of economical offences. Among them, black marketeers, but also people who had illegally slaughtered animals or had stolen goods from the Wehrmacht.

From February 1943 onwards, part of the camp functioned as Geisellager (hostage camp). Here around 600 hostages were accommodated. They were for example detained as a retribution for resistance actions. Amongst them were ‘family hostages’, people who were arrested by the Sicherheitspolizei (security police) because a relative of them was a fugitive. In May 1943 a separate camp was set up for arrested women, Jewish women and wives and children of hostages.

Just like in all other official concentration camps, the prisoners in camp Vught had to perform hard labour. That’s why in most concentration camps mainly adult prisoners stayed who were suitable for work and therefore no children. Camp Vught, however, was an exemption. Here hundreds of Jewish children were locked up. A few weeks after the arrival of the first children, a separate part of the camp was especially allocated for them. Children were separated from their parents and housed in special barracks. A couple of adults took care of them. Every now and then they were allowed to see their own parents. Each children’s barracks housed 240 children in the ages of four to sixteen. Mothers with babies and children up to four years were put up in special barracks. Children older than sixteen were spread out among the different adult barracks.

Koos Valk was nine years old when he was detained in camp Vught. Ultimately he was transported to the camp-ghetto Theresienstadt, but survived the war. He described his first night in Vught as follows: "I was put up in a red brick barrack number 3 together will all nine year olds. I had to find a bed which was not yet occupied. I cried. A boy saw me and said: ‘you can stay in my bedbunk.’ The bed under him was still free. I still hadn’t eaten and softly crying I pulled the cover over my head. The matrass from the boy above me was broken. Each time he moved, stuff fell down, so I buried my face in the blanket. From the cloths I had been given I had to make a pile to put under my head. It was an awful affair. That was my first night in Vught."

To keep the children busy, a school was set up for them in March 1943. The continued existence of the school was constantly under pressure, because several times a teacher had been deported. When on 7 April 1943, the prisoners were put up in the school barracks the teachers tried to continue with the lessons in the living barracks.

The children in camp Vught were treated with indifference by the camp leaders and they were not even spared the exhausting roll call. Camp prisoner David Koker wrote on 6 March 1943 that a festive afternoon for the children was interrupted by the roll call. He wrote: "It is more unheard off to military drill imprisoned children than to mistreat them. When I saw the children stand there this afternoon, saw them standing there for so long, on their spoiled social afternoon at which they had looked forward too, I saw for the first time what so many others had seen for a long time: how low we have fallen." Normally there was never a roll call on Saturday afternoon. The next day about 32 of the 150 children had fallen ill.

On 30 April 1943, 1,800 Jewish children were staying in the camp. The hygiene of the children’s barracks was bad and there was a shortage of food. Many children were ill and some died, for instance due to the measles. The high child mortality rate became known outside the camp and again the Nazi command tried to end the negative publicity. The solution was extremely rigid and awful: all children were deported to the extermination camps in the east. All children died here.

In camp Vught itself, at least 421 children, women and men died due to hunger, illness and ill-treatment. Especially in the first months, many prisoners died because of bad living conditions. This changed when in the course of 1943, large scale relief actions were started on the outside. Jewish prisoners, however, depended solely on friends and relatives, because the Red Cross was not allowed to give them food parcels. Jews were starving massively, until the Jewish Council was given permission to provide food parcels. This consent was later revoked again.

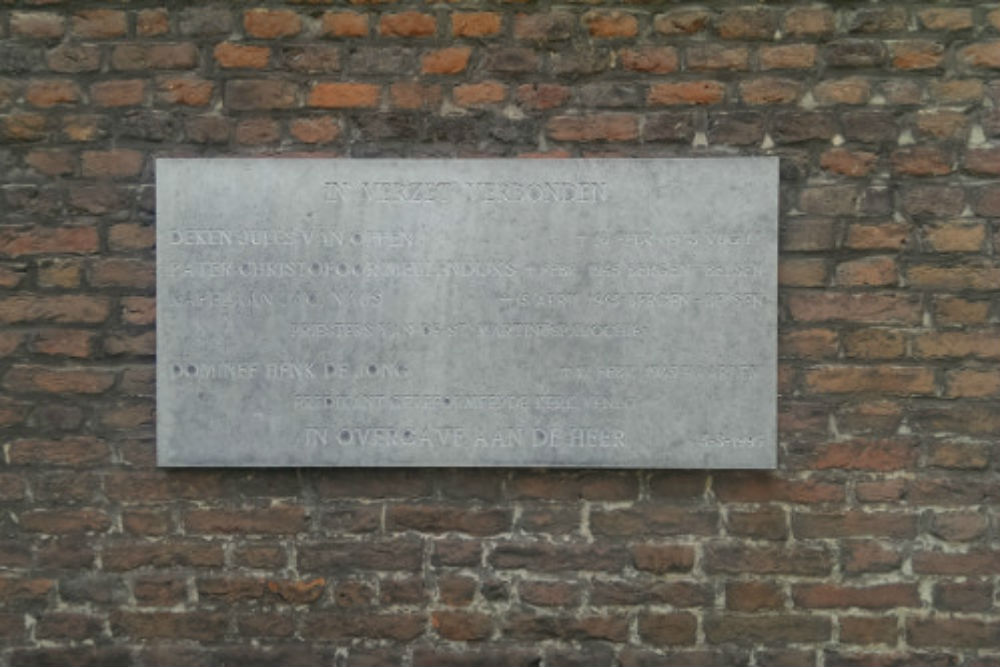

Since the camp opened, a German Standesbeamte (civil servant) worked there. He would draw up a certificate for every prisoner who died in camp Vught. The certificate included personal details and the cause of death. The certificates were incorporated in the Sterbebuch (death book). Despite the fact that not all certificates were preserved, after the war they tried to retrieve the names of all victims. Nowadays, their names can be found on the special commemoration wall on the site of the former camp Vught.

Besides the 421 prisoners who died due to hunger, illness and ill-treatment, 329 prisoners were executed at the execution site just outside camp Vught. The firing squad was mainly made up of Dutch SS-ers, who were charged with the outside surveillance. The first execution took place in June 1944. The victim was a prisoner who was found guilty of sabotage at the Philips-Kommando. In August and September 1944, executions took place one after the other. After the war, one of the prisoners said that the shots from the shooting range could be heard more and more often during those two months: "(...) even during morning roll call. This morning two salvos. After the first salvo, I count nineteen shots and shiver all over my body. Out of anger, I bite my lower lip to suppress my tears for these horrible bloodbaths, which never seems to end."

The massive executions in August and September 1944 were the result of the situation at the front. The Allies were ever more successful and advanced towards Germany. To prevent civilians in the occupied areas from offering resistance under the influence of the Allies, Adolf Hitler ordered the Niedermachungsbefehl on 30 July 1944. On the basis of this order, the judgment against ‘saboteurs’ expired. Everyone who was suspected of sabotage or other acts of resistance could be sentenced to death without any form of jurisdiction. It was meant as a deterrent. In the Netherlands, prisoners were transferred to camp Vught from various different prisons, but mainly from ‘the Oranje hotel’ - the convict prison in Scheveningen - to be executed. After the evacuation of the camp in September 1944, people living in the neighbourhood placed a wooden cross at the execution site in memory of the 329 executed prisoners. Nearby this commemoration mark a monument was revealed by princess Juliana on 20 December 1947.

Definitielijst

- Arbeitseinsatz

- “Labour deployment”. Forced deployment in the German industry. Approximately 11 million European citizens were rounded up and deployed into forced labour in the Third Reich. Not to be confused with the Arbeidsdienst or labour service, an organisation for national-socialist education for Dutch youngsters.

- ghetto

- Part of a town separated from the outside world to segregate Jewish population. The establishment of ghettos was intended to exclude the Jews from daily life and from the rest of the people. From these ghettos it was also easier to deport the Jews to the concentration and extermination camps. Also known as “Judenviertel” or Jewish quarter.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Theresienstadt

- City in the Czech Republic. Here the Nazis established a model concentration camp.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Images

Hard labour

At the time that camp Vught was taken into use, there was a shortage of workmen, especially in Germany, because many men were fighting at the front. That’s why companies could deploy camp prisoners to keep up the war production. These companies had to pay a remuneration to the SS for the prisoners that were assigned to them as workmen. In camp Vught adult prisoners also had to do hard labour for companies such as Philips and Continental. They were assigned to so-called Arbeitskommandos, work groups that had to perform work inside and outside the camp. Not all Arbeitskommandos worked for companies, because daily work also had to be done in the camp. Below you can find an overview of important workplaces in the camp and the immediate vicinity:

| Kitchen and laundry room | |

| Schreibstube | Camp administration |

| Bauernhof | Farm in the camp where 150 prisoners worked. |

| Druckerkommando | Camp printer. Here arrested illegal printers were forced to copy illegal magazines and flyers. However, the text was adjusted, so that the contents was no longer true. |

| Philips-workplace / Philips-Kommando | Workplace of Philips where about 1,200 Jewish and non-Jewish prisoners made radio equipment, radio tubes, flashlights with manual dynamo and electric shavers. |

| Company Escotex | Production of clothing and fur. |

| Company Menist | Sorting company of old clothes. |

| Zerlegbetieb / Luftwaffe-Kommando | Crashed German, British and American aircraft were disassembled here by hand by around 500 prisoners. This was a particular heavy Kommando. |

| Continental rubberwerken | Production of gas masks. This work was being done by female prisoners. |

The history of the Philips-Kommando is remarkable, because Philips did not have the intention to profit from cheap prisoners, but to provide as many prisoners as possible with a roof over their head to safeguard them from being deported to Germany or Poland. There was never any aspiration of making a profit. A workspot in the Philips-Kommando was of vital importance to Jews, because in this way they could postpone deportation to extermination camps.

During the 18 months that the special Philips workplace B 677 existed – from February 1943 to September 1944 – over 3,100 prisoners, around 2,200 men and 900 women, worked here for a short or longer period of time. Amongst them were 469 Jewish prisoners, mostly women. About 10% of all prisoners in Vught worked in the Philips workplace.

The management of Philips, led by 37-year old Frits Philips, only agreed to create a workplace in camp Vught after a long while. The decision was taken after the resistance had been consulted. Moreover, Philips stipulated a couple of demands. During a radio interview in 1986, Frits Philips said that he had declined an initial request. He then wondered if it could be "that I had stipulated so many demands that people would be better off, without improving the German war efforts." His conditions were that prisoners "would not have to work more than a certain number of hours; that they would work there under the guidance of Philips staff; could enter and exit the camp freely; that Philips would determine how much products they had to make; what they had to do and who had to do what; that Philips could determine which people would work where and who couldn’t; that Philips would provide for warm meals in the camp and that they would be paid extra if Philips would determine so." To his surprise, all demands that he had stated, were accepted, except the demand for extra pay.

Because the SS generally stuck to the agreements made with Philips, the working conditions for the prisoners who worked at the Philips workplace were not heavy compared to other Arbeitskommandos. The Philips prisoners received better food, the so-called ‘Phili-mash’ and the management of Philips continued with their efforts of trying to obtain permission for certain measures that would improve the lives of the prisoners. This resulted in extra work breaks, the absence of SS guards on the work floor, music during work and medical care. The Philips management tread on dangerous ground by asking for permission for such benefits, but because Philips stated that this would benefit production, the SS gave in to these requests. Besides this, the SS benefited from a good collaboration with Philips, because for every prisoner that worked for Philips, it received a daily remuneration of 4.50 guilders for a trained worker and 3 guilders for a non-trained worker. Women were considered non-trained workers.

The supervision of the Special Workplace B677 was in the hands of R.E. Laman Trip. He was not a prisoner, but one of the employees of Philips, the so-called Philips-Zivilisten, who would travel to Vught on a daily basis in order to supervise the Philips workplace. He was assisted by organiser C.H. Braakman, technician G.H. Peuscher and a dozen other employees. Daily management of the workplace was performed by prisoners who were part of the Häftlinge-staff (prisoner staff). The first three staff members were Bram de Wit as technical manager, Dirk Wassink, who was in charge of personnel and operation and Arie Heijkoop responsible for administration. After their release they were succeeded by Piet Hamburg, Aad van den Berg and Cor van Water.

In May 1944 camp commander SS-Sturmbannführer Hans Hüttig ended the special position held by the Philips-Kommando. He had become aware of the fact that sabotage had taken place in the Philips workplace. Various products from the workplace had been manufactured to such a degree that they would break down after a short period of time. All Jewish workers were deported to Auschwitz and over 250 non-Jewish men were transferred to Dachau. Also some Philips-Zivilisten were arrested, some of which went into hiding. The Kommando was continued under German command and 750 new prisoners, but the Philips-Kommando came to a definite end when camp Vught was evacuated in September 1944.

From the 469 Jewish prisoners who had worked in the Philips-Kommando, 382 survived the war. In 1996 Frits Philips received the Yad Vashem decoration as gratitude for helping the Jews by founding the Philips-Kommando. This decoration is presented by the state of Israel to non-Jews who have dedicated themselves to saving Jews during the Second World War. Receivers of this decoration also receive the honour title Righteous Among the Nations.

Definitielijst

- collaboration

- Cooperation of the people with the occupying forces, more generally spoken the term for individuals who cooperate with the occupying force is collaborator.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Luftwaffe

- German air force.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Yad Vashem

- Yad Vashem is Israel’s national Holocaust memorial where in addition to Jewish victims and resistance heroes, also non-Jewish helpers of Jews during the World War 2 are being honoured. Those non-Jewish are called the Righteous Among The Nations. Until the mid 90’s trees were planted for these rescuers. In 1996 a special remembrance garden was established displaying all of the names of the helpers. Every year new names are added.

Images

The aircraft demolition was supposedly the harshest Arbeitskommando of camp Vught. Source: www.nmkampvught.nl.

The aircraft demolition was supposedly the harshest Arbeitskommando of camp Vught. Source: www.nmkampvught.nl. Frits Philips, from 1939 president of Philips. Source: www.philips-kommando.nl.

Frits Philips, from 1939 president of Philips. Source: www.philips-kommando.nl. Dynamo lamps, as they were made in the Philips workplace. Source: www.philips-kommando.nl.

Dynamo lamps, as they were made in the Philips workplace. Source: www.philips-kommando.nl.Außenlager / Außenkommandos

| Location: | Amersfoort |

| Opened: | 17 May 1943 (first opening) |

| Closed: | July 1943 (last entry) |

| Prisoners: | Men |

| Work: | Building shooting ranges for the Luftwaffe. |

| Remarks: | This Außenlager was housed in the Polizeiliches Durchgangslager in Amersfoort. |

| Location: | Arnhem |

| Opened: | July 1943 (first entry) |

| Closed: | August 1943 (last entry) |

| Prisoners: | Men |

| Work: | Building shooting ranges for the Luftwaffe. |

| Remarks: | The prisoners were accommodated in the Coehoorn barracks. |

| Location: | Arnhem |

| Opened: | 22 January 1944 (first entry) |

| Closed: | 5 September 1944 (last entry) |

| Prisoners: | Men |

| Prisoners deployed by: | Bauleitung of the Luftwaffe. |

| Work: | Building work at the airport of Deelen. |

| Location: | Eindhoven |

| Opened: | 2 September 1943 (first entry) |

| Closed: | 9 June 1944 (last entry) |

| Prisoners: | Men |

| Prisoners deployed by: | Philips and Bauleitung of the Luftwaffe. |

| Work: | Building work at the airport. |

| Location: | Gilze Rijen |

| Opened: | 30 August 1943 (first entry) |

| Closed: | 18 May 1944 (last entry) |

| Prisoners: | Men |

| Prisoners deployed by: | Bauleitung of the Luftwaffe. |

| Work: | Building work at the airport. |

| Remarks: | Surveillance was done by men of the Luftwaffe. |

| Location: | Haaren |

| Opened: | January 1943 (first entry) |

| Closed: | September 1944 |

| Prisoners: | Men |

| Prisoners deployed by: | Befehlshaber der Sicherheitspolizei und der SD (BdS) the Netherlands. |

| Work: | Camp work in police prison / hostage camp. |

| Remarks: | The prisoners were put up in a prison / hostage camp. |

| Location: | Leeuwarden |

| Opened: | 27 February 1944 |

| Closed: | 8 March 1944 |

| Prisoners: | Men |

| Prisoners deployed by: | Bauleitung of the Luftwaffe. |

| Work: | Bomb tracing at the airport. |

| Remarks: | The prisoners were put up in a prison. |

| Location: | Moerdijk |

| Opened: | 26 March 1943 (first entry) |

| Closed: | 23 February 1944 (last entry) |

| Prisoners: | Men |

| Work: | Digging out tank ditches at the Moerdijk bridge. |

| Location: | Roosendaal |

| Opened: | 24 February 1944 (first entry) |

| Closed: | 18 April 1944 (last entry) |

| Prisoners: | Men |

| Work: | Coastal defence work (building fortifications). |

| Remarks: | The prisoners were put up in an agricultural college. |

| Location: | The Hague |

| Opened: | September 1943 (first entry) |

| Closed: | July 1944 (last entry) |

| Prisoners: | Men |

| Prisoners deployed by: | BdS The Netherlands. |

| Location: | ’s-Hertogenbosch |

| Opened: | December 1943 |

| Closed: | September 1944 |

| Prisoners: | Women |

| Prisoners deployed by: | Continental-Gummiwerke AG. |

| Work: | Manufacturing gas masks. |

| Remarks: | The camp was located in the building of Continental in ’s-Hertogenbosch. |

| Location: | St. Michielsgestel |

| Opened: | January 1943 |

| Closed: | September 1944 |

| Prisoners: | Men |

| Prisoners deployed by: | BdS The Netherlands. |

| Work: | Camp work in a Geisellager. |

| Remarks: | The prisoners were put up in a Geisellager. |

| Location: | Venlo |

| Opened: | September 1943 (first entry) |

| Closed: | September 1944 (last entry) |

| Prisoners: | Men |

| Prisoners deployed by: | Bauleitung of the Luftwaffe. |

| Work: | Construction of an airport. |

Definitielijst

- Luftwaffe

- German air force.

Images

Camp personnel

As was the case in each concentration camp, the inside and outside surveillance in camp Vught consisted of two separate components. The outside surveillance was performed by the fourth and fifth company of the SS-Wachbataillon Nordwest. This Wachbataillon fell under command of the Waffen-SS and consisted of Dutch and Ukrainian men. From 26 July to 6 September 1944, this unit took part in hundreds of executions at the execution site of camp Vught.

The inside surveillance was mainly in the hands of German SS-men. They were under command of the Amtsgruppe D (Konzentrationslager) of the SS-Wirtschafts- und Verwaltungshauptamt. The camp commander was in charge of the inside surveillance. Camp Vught had three camp commanders: SS-Hauptsturmführer Karl Walter Chmielewski, SS-Sturmbannführer Adam Grünewald and SS-Sturmbannführer Hans Hüttig.

SS-Hauptsturmführer Karl Walter Chmielewski was the first camp commander of camp Vught. When he was appointed he was 39 years old. Before his appointment to camp commander in Vught he had already worked in several concentration camps. From 1935 to 1936 he worked at Columbia Haus, one of the first concentration camps (frühe Konzentrationslager), in the neighbourhood Tempelhof in Berlin. Subsequently he worked in Sachsenhausen from 1937 to 1940 and in Mauthausen from 1940 to 1943. In his early career he committed several crimes as camp guard. Chmielewski was in command of camp Vught in the chaotic and especially for many prisoners fatal early months of the camp. Nevertheless he succeeded to structure in a disciplined manner the abominable conditions of the ever growing incoming stream of prisoners in a relatively short period of time. Chmielewski was involved in the establishment of the Philips-Kommando. His position as camp commander came to an end when he was discharged in October 1943 because of embezzlement. He supposedly seized diamonds from prisoners, which he then sent to his own family. Other sources claim that he had sold products from the Philips workplace on the black market. After the war, he was sentenced to life imprisonment.

Chmielewski was succeeded by the 40-year old SS-Sturmbannführer Adam Grünewald. Originally he was a baker, but had been working in concentration camps since 1934. His career started in the frühe Konzentrationslager Lichtenburg where he worked until 1937. In 1938 he worked in Buchenwald and from 1938 to 1939 he was appointed as Schutzhaftlagerführer in Dachau. Before he became camp commander in Vught in 1943, he worked in Sachsenhausen in 1942. Grünewald had a bad reputation and had been convicted by the SS once to three years imprisonment. In camp Vught he introduced a strict regime. After only three months he was fired as camp commander and degraded to the position of soldier because of his part in the Bunker Tragedy in January 1944. During the last year of the war, Grünewald served in the 3. SS-Panzer-Division Totenkopf. He was killed in battle in Hungary in 1945.

The last camp commander of camp Vught was the 50-year-old First World War veteran SS-Sturmbannführer Hans Hüttig. Just like his predecessors Chmielewski and Grünewald he had worked in several concentration camps before he started working in Vught. In 1936, he worked in the frühe Konzentrationslager (early concentration camp) Lichtenburg. He then worked in Sachsenhausen in 1937 and in in Buchenwald in 1938. From 1939 to 1942 he worked in Flossenbürg and before his appointment in Vught he was camp commander in Natzweiler in 1942. In camp Vught he set things right and took some drastic measures. He ended the independence of the Philips workplace and made the camp Judenrein (free from Jews). Not only was he responsible for the deportation of Jews from the camp, he also ordered the execution of at least 329 persons in the summer of 1944. After camp Vught was closed down, Hüttig served in the 34. SS-Freiwilligen-Grenadier-Division Landstorm Nederland in the last months of war. After the war, he was sentenced to life imprisonment, however, he was released early in 1956.

The camp surveillance were assisted by Kapos, prisoners who were deployed to instil ‘order and discipline’ into their fellow prisoners. They started with 80 Kapos in camp Vught. Some of them were German political prisoners, but most of them were German criminals, who often had committed murder. Especially the criminals who were deployed as Kapo took a hard line against prisoners.

Definitielijst

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Kapo

- A Kapo was a prisoner in a concentration camp in Nazi Germany during World War 2 who was assigned to supervise other prisoners. A Kapo had to supervise the work of the prisoners and was responsible for their results on behalf of the SS.

- Landstorm

- Before 1940 this term designated the various volunteer formations the army in the Netherlands. It was dissolved shortly after the German invasion in May 1940.

- Landstorm Nederland

- During the German occupation a territorial unit of the Waffen-SS quartered in the Netherlands, consisting of mainly Dutch volunteers. Initially established as the Landwacht Nederland in March1943 the name was later changed because another organisation with the same name was established. The Landstorm was deployed against the Allies. At its peak it numbered 8,000 men. It was known as the 34. SS- Freiwilligen-Grenadier-Division Landstorm Nederland. In 1944 a total of 22,000 Dutchmen served in the Waffen-SS.

- Mauthausen

- Place in Austria where the Nazi’s established a concentration camp from 1938 to 1945.

- Totenkopf

- “Death’s head”. Symbol that was used by the SS. Also the name of an SS Division.

- Waffen-SS

- Name of Military section of the SS.

Images

Karl Walter Chmielewski, the first camp commander of camp Vught. Source: www.philips-kommando.nl.

Karl Walter Chmielewski, the first camp commander of camp Vught. Source: www.philips-kommando.nl. Adam Grünewald, the successor of Chielewksi. Source: www.philips-kommando.nl.

Adam Grünewald, the successor of Chielewksi. Source: www.philips-kommando.nl. Hans Hüttig, the last camp commander of camp Vught. Source: www.philips-kommando.nl.

Hans Hüttig, the last camp commander of camp Vught. Source: www.philips-kommando.nl.Deportations

Within the organisation of the Endlösung (final solution) – the plan of the Nazis to exterminate European Jews – camp Vught played a minor roll when compared to Judendurchgangslager Westerbork, the Dutch transition station between the extermination camps. From camp Vught no direct deportations took place to the extermination camps. Nevertheless, about 12,000 Jews were imprisoned in Vught for a short or longer period of time. Almost all of them were subsequently deported to extermination camps in Poland via camp Westerbork.

The Jewish prisoners in Vught were divided into two groups: the Schutzhaft-Jews and the civil Jews. Schutzhaft-Jews were Jews who were punished for a particular offence. They would first be put up with other Schutzhaft-prisoners in the Schutzhaftlager. Later they were accommodated in separate barracks, called Block 15. As of 16 January 1943, the civil Jews stayed in a separate part of the camp that was arranged as Judenauffanglager (Jew shelter camp). There were two groups of civil Jews. The first group of civil Jews, mainly consisted of workers from the textile and diamond industry who enjoyed exemption from deportation on the basis of their work expertise. The second group was made up of Jews from the Dutch provinces of Friesland, Groningen, Drenthe, Overijssel, Gelderland, Limburg, North-Brabant and Zeeland. They had to report themselves in camp Vught, because these provinces had to be Judenrein as of 10 April 1943. In February 1943 the part of the camp for Jews was no longer designated as Judenauffanglager, but as Judendurchgangslager (JDL, transition station), although the Jewish prisoners were not informed of this.

Jewish self-government was allowed in the Judendurchgangslager. The Jewish prisoners had their own officials responsible for order and SS guards hardly interfered with daily camp management.

The first Jews transport to Vught took place on 15 January 1943. The Germans had brought together a couple of hundred Jews in the Dutch Theatre in Amsterdam. In the night of 15 to 16 January, 453 Jews were transported via tram to Amsterdam Central Station. From there, the Jews were transported to Vught, where they arrived in the early morning of 16 January. In the following months, many more transports would take place.

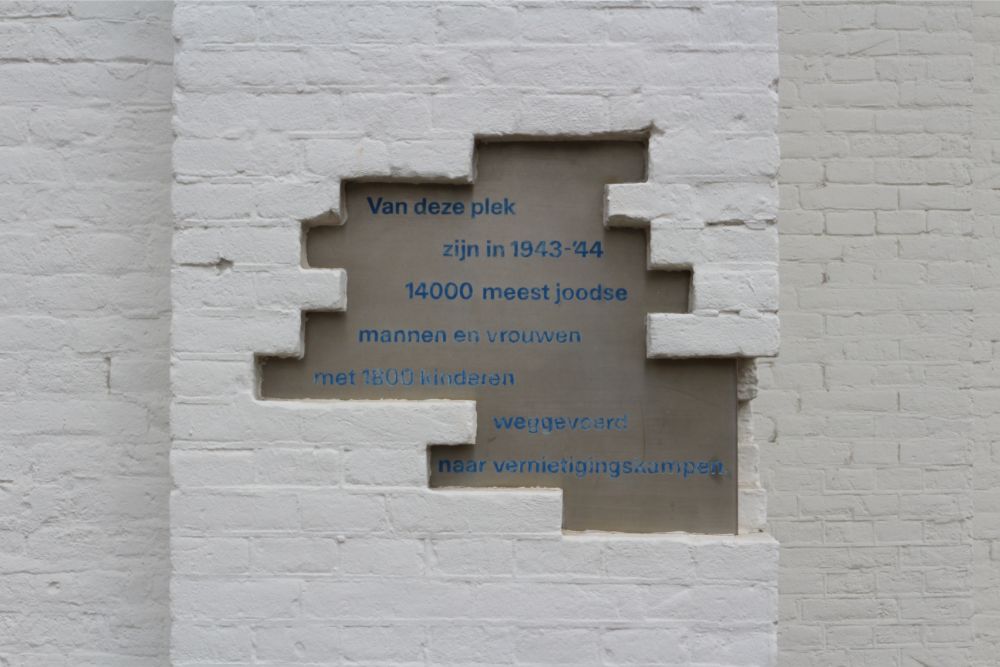

The first Jews transport from Vught to Westerbork took place on 28 January 1943. In the following years, many more transports would take place, including the infamous transports of children on 6 and 7 June 1943. In total, 1269 Jewish children, together with 1745 parents were deported to the extermination camp Sobibor, from Vught via Westerbork. After a journey of three days they would be killed in this extermination camp almost immediately upon arrival. On 5 September 1999, a special monument for the deported children was revealed. Because the transport lists of 6 and 7 June 1943 were kept, all the names and ages of the children could be listed on the monument.

The last transport from Vught departed on 2 June 1944 to Auschwitz. It concerned the group of Jewish workers of the Philips workplace. Of this group of about 500 people, 382 of them survived the war, while of the other deported Jews only a small part returned home. Non-Jewish prisoners were also deported from camp Vught. They were not deported to extermination camps, but to other camps, prisons or detention centres. The total numbers involved are unknown.

Definitielijst

- Endlösung

- Euphemistic term for the final solution the Nazis had in store for the “Jewish problem”. Eventually the Endlösung would get the form of annihilating the entire Jewish people in extermination camps.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

Images

Deportation in camp Westerbork. Source: Jewish Virtual Library.

Deportation in camp Westerbork. Source: Jewish Virtual Library.Liberation and after the war

On Dolle Dinsdag (Mad Tuesday) on 5 September 1944, the SS-men in camp Vught did not want to await the approaching allied troops. They evacuated the camp in a hurry. After the last Jews transport on 2 June 1944, the remaining male prisoners were deported to Sachsenhausen from 5 June onwards. The still remaining women were relocated to Ravensbrück on 5 September 1944. A district nurse from Vught took over the daily management of the camp on 12 September 1944 on behalf of the Red Cross.

On 26 October 1944, camp Vught was freed by the Allies, but by then all prisoners had been put on transport, so all they found was an empty camp. The camp site was put into use by the Canadians. Thousands of people were temporarily put up in the camp, including Germans who were evacuated from the border region.

After the war, the former concentration camp Vught served as an internment camp for a while for Dutch citizens who were suspected of collaboration and war crimes. A total of 7,000 collaborators were accommodated here, including 300 Dutch SS-men. The SS-men had to wear the striped uniforms that used to be worn by the camp prisoners.

After the last prisoners had left, the barracks were temporarily vacant. In 1951, the vacant camp complex was used to accommodate southern Moluccan militaries and their families. They had fought alongside the Dutch army in the battle against the proclaimed Republic of Indonesia. After the Dutch had definitely retreated, it was no longer safe for them to stay in Indonesia. It was the intention that they would only stay there for a short period of time, but this was a miscalculation. It is true that the Moluccan community in the so-called living area Lunetten has become smaller in size, but they are still living there. Since 1992 they have left the barracks and reside in newly build houses. All the old barracks have been demolished, with the exception of one, which is partly used as a church and is a listed building. Some of the new houses have been designed in the shape of the original barracks.

Besides the Moluccan living area Lunetten, also a prison, two army barracks and the National Monument camp Vught can be found on the former camp site. On the site of the Van Brederode army barracks a number of original buildings are still present, where among other things, SS-guards were housed during the war. These are also listed buildings.

Thanks to the efforts of the Foundation National Monument Camp Vught, which was founded in 1986, the National Monument was realised on a small part of the former camp site. On 18 April 1990 the National Monument was opened to the public by Queen Beatrix. In 2002, a new commemoration centre was built and the camp site was restored as much as possible to its original state. The National Monument Camp Vught keeps "the memory to the history of the camp and the victims alive. In words and images, also current forms of prejudices, discrimination and racism are being showed. This makes it tangible how – even in these days – personal choices of individuals can lead to suppression and the shutting out of other people in society."

Definitielijst

- collaboration

- Cooperation of the people with the occupying forces, more generally spoken the term for individuals who cooperate with the occupying force is collaborator.

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- racism

- Discrimination based on race.

- war crimes

- Crimes committed in wartime. Often concerning crimes committed by soldiers against civilians.

Images

The Moluccan living area Lunetten. Source: www.nmkampvught.nl.

The Moluccan living area Lunetten. Source: www.nmkampvught.nl. Queen Beatrix during the inauguration of the National Monument Camp Vught on 18 April 1990. Source: www.nmkampvught.nl.

Queen Beatrix during the inauguration of the National Monument Camp Vught on 18 April 1990. Source: www.nmkampvught.nl.Information

- Article by:

- Kevin Prenger

- Translated by:

- STIWOT translator

- Published on:

- 30-05-2015

- Last edit on:

- 02-05-2020

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Related books

Sources

- KOK, R. & SOMERS, E., Nederland en de Tweede Wereldoorlog, Waanders, Zwolle, 2005.

- KORPEL, A., De Waard in oorlogstijd 2, De Klaroen, Alblasserdam, 1984.

- PRESSER, J., Ondergang, Aspekt, Soesterberg, 2005.

- SPECTOR, S. & ROZETT, R., Encyclopedie van de Holocaust, Kok, Kampen, 2004.

- TIJENK, C., Weggehaald - Joodse kinderen en het kamp Vught, Vught, Vriendenkring Nationaal Monument Vught, 2004.

- UIJLAND, M., TIJENK, C., Eindpunt of tussenstation - Gids Nationaal Monument Kamp Vught, Vught, Stichting Nationaal Monument Vught, 2002.

- www.keom.de

- www.nmkampvught.nl

- www.philips-kommando.nl

- www.waffen-ss.nl